BIRD CONSERVATION the Magazine of American Bird Conservancy Fall 2012 BIRD’S EYE VIEW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Checklist Guánica Biosphere Reserve Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture BirD CheCklist Guánica Biosphere reserve Puerto rico Wayne J. Arendt, John Faaborg, Miguel Canals, and Jerry Bauer Forest Service Research & Development Southern Research Station Research Note SRS-23 The Authors: Wayne J. Arendt, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Sabana Field Research Station, HC 2 Box 6205, Luquillo, PR 00773, USA; John Faaborg, Division of Biological Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211-7400, USA; Miguel Canals, DRNA—Bosque de Guánica, P.O. Box 1185, Guánica, PR 00653-1185, USA; and Jerry Bauer, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Río Piedras, PR 00926, USA. Cover Photos Large cover photograph by Jerry Bauer; small cover photographs by Mike Morel. Product Disclaimer The use of trade or firm names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture of any product or service. April 2015 Southern Research Station 200 W.T. Weaver Blvd. Asheville, NC 28804 www.srs.fs.usda.gov BirD CheCklist Guánica Biosphere reserve Puerto rico Wayne J. Arendt, John Faaborg, Miguel Canals, and Jerry Bauer ABSTRACt This research note compiles 43 years of research and monitoring data to produce the first comprehensive checklist of the dry forest avian community found within the Guánica Biosphere Reserve. We provide an overview of the reserve along with sighting locales, a list of 185 birds with their resident status and abundance, and a list of the available bird habitats. Photographs of habitats and some of the bird species are included. -

Belize), and Distribution in Yucatan

University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland Institut of Zoology Ecology of the Black Catbird, Melanoptila glabrirostris, at Shipstern Nature Reserve (Belize), and distribution in Yucatan. J.Laesser Annick Morgenthaler May 2003 Master thesis supervised by Prof. Claude Mermod and Dr. Louis-Félix Bersier CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1. Aim and description of the study 2. Geographic setting 2.1. Yucatan peninsula 2.2. Belize 2.3. Shipstern Nature Reserve 2.3.1. History and previous studies 2.3.2. Climate 2.3.3. Geology and soils 2.3.4. Vegetation 2.3.5. Fauna 3. The Black Catbird 3.1. Taxonomy 3.2. Description 3.3. Breeding 3.4. Ecology and biology 3.5. Distribution and threats 3.6. Current protection measures FIRST PART: BIOLOGY, HABITAT AND DENSITY AT SHIPSTERN 4. Materials and methods 4.1. Census 4.1.1. Territory mapping 4.1.2. Transect point-count 4.2. Sizing and ringing 4.3. Nest survey (from hide) 5. Results 5.1. Biology 5.1.1. Morphometry 5.1.2. Nesting 5.1.3. Diet 5.1.4. Competition and predation 5.2. Habitat use and population density 5.2.1. Population density 5.2.2. Habitat use 5.2.3. Banded individuals monitoring 5.2.4. Distribution through the Reserve 6. Discussion 6.1. Biology 6.2. Habitat use and population density SECOND PART: DISTRIBUTION AND HABITATS THROUGHOUT THE RANGE 7. Materials and methods 7.1. Data collection 7.2. Visit to others sites 8. Results 8.1. Data compilation 8.2. Visited places 8.2.1. Corozalito (south of Shipstern lagoon) 8.2.2. -

Literature Cited Proposed Critical Habitat Designation for Elfin-Woods Warbler (EWWA), Setophaga Angelae

Literature Cited Proposed Critical Habitat Designation for Elfin-woods Warbler (EWWA), Setophaga angelae Abt Associates, Inc. 2016. Screening analysis of the likely economic impacts of critical habitat designation for the elfin-woods warbler. March 7, 2016 memo to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Aide, T. M. and M. Campos. 2016. Elfin-woods warbler acoustic monitoring. Preliminary report: Carite. Prepared for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 10 pp. Anadón-Irizarry, V. 2006. Distribution, habitat occupancy and population density of the elfin-woods warbler (Dendroica angelae) in Puerto Rico. Master’s Thesis. University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus. 53 pp. Anadón-Irizarry, V. 2014. Personal communication regarding the searching for a third population of the elfin-woods warbler. Caribbean Program Manager, Birdlife International Inc. E-mail: November 10, 2014. Arendt, W.J., S.S. Qian, and K.A. Mineard. 2013. Population decline of the elfin-woods warbler Setophaga angelae in eastern Puerto Rico. Bird Conservation International, Birdlife International 2013. 11 pp. Arroyo-Vázquez, B. 1992. Observations of the breeding biology of the elfin-woods warbler. Wilson Bulletin 104:362-365. Colón-Merced, R. 2013. Evaluación cuantitativa de presas potenciales, tipo artrópodo, y análisis paisajista del hábitat potencial para la Reinita de Bosque Enano (Setophaga angelae) en Puerto Rico. Master’s Thesis. University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus. 126 pp. Delannoy, C.A. 2007. Distribution, abundance and description of habitats of the elfin- woods warbler Dendroica angelae, in southwestern Puerto Rico. Final Report submitted to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under Grant Agreement No. 401814G078. University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus. -

Perú: Cordillera Escalera-Loreto Perú: Cordillera Escalera-Loreto Escalera-Loreto Cordillera Perú: Instituciones Participantes/ Participating Institutions

.................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................no. 26 ....................................................................................................................... 26 Perú: Cordillera Escalera-Loreto Perú: Cordillera Escalera-Loreto Instituciones participantes/ Participating Institutions The Field Museum Nature and Culture International (NCI) Federación de Comunidades Nativas Chayahuita (FECONACHA) Organización Shawi del Yanayacu y Alto Paranapura (OSHAYAAP) Municipalidad Distrital de Balsapuerto Instituto de Investigaciones de la Amazonía Peruana (IIAP) Herbario Amazonense de la Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana (AMAZ) Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos Centro -

Bird Species and Climate Change

Bird Species and Climate Change The Global Status Report: A synthesis of current scientific understanding of anthropogenic climate change impacts on global bird species now, and projected future effects. Report Climate Risk Climate A Climate Risk Pty Ltd are specialist advisors to business and government on risk, opportunity and adaptation to climate change. Climate Risk www.climaterisk.net Climate Risk Pty Limited (Australia) Level 1, 36 Lauderdale Avenue Fairlight, NSW 2094 Tel: + 61 2 8003 4514 Brisbane: + 61 7 3102 4513 www.climaterisk.net Climate Risk Europe Limited London: + 44 20 8144 4510 Manchester: + 44 16 1273 2474 This report was prepared by: Janice Wormworth BSc MA [email protected] Dr Karl Mallon BSc PhD Tel: + 61 412 257 521 [email protected] Bird Species and Climate Change: The Global Status Report version 1.0 A report to: World Wide Fund for Nature The authors of this report would like to thank our peer reviewers, including Dr. Lara Hansen and Prof. Rik Leemans. We would also like to thank Corin Millais, Paul Toni and Gareth Johnston for their input. ISBN: 0-646-46827-8 Designed by Digital Eskimo www.digitaleskimo.net Disclaimer While every effort has been made to ensure that this document and the sources of information used here are free of error, the authors: Are not responsible, or liable for, the accuracy, currency and reliability of any information provided in this publication; Make no express or implied representation of warranty that any estimate of forecast will be achieved or that any statement -

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers

Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brandan L. Gray August 2019 © 2019 Brandan L. Gray. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers by BRANDAN L. GRAY has been approved for the Department of Biological Sciences and the College of Arts and Sciences by Donald B. Miles Professor of Biological Sciences Florenz Plassmann Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT GRAY, BRANDAN L., Ph.D., August 2019, Biological Sciences Ecology, Morphology, and Behavior in the New World Wood Warblers Director of Dissertation: Donald B. Miles In a rapidly changing world, species are faced with habitat alteration, changing climate and weather patterns, changing community interactions, novel resources, novel dangers, and a host of other natural and anthropogenic challenges. Conservationists endeavor to understand how changing ecology will impact local populations and local communities so efforts and funds can be allocated to those taxa/ecosystems exhibiting the greatest need. Ecological morphological and functional morphological research form the foundation of our understanding of selection-driven morphological evolution. Studies which identify and describe ecomorphological or functional morphological relationships will improve our fundamental understanding of how taxa respond to ecological selective pressures and will improve our ability to identify and conserve those aspects of nature unable to cope with rapid change. The New World wood warblers (family Parulidae) exhibit extensive taxonomic, behavioral, ecological, and morphological variation. -

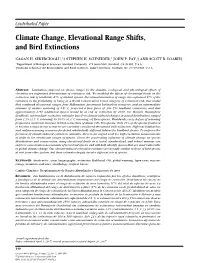

Climate Change, Elevational Range Shifts, and Bird Extinctions

Contributed Paper Climate Change, Elevational Range Shifts, and Bird Extinctions CAGAN H. SEKERCIOGLU,∗‡ STEPHEN H. SCHNEIDER,∗ JOHN P. FAY,† AND SCOTT R. LOARIE† ∗Department of Biological Sciences, Stanford University, 371 Serra Mall, Stanford, CA 94305, U.S.A. †Nicholas School of the Environment and Earth Sciences, Duke University, Durham, NC 27707-0328, U.S.A. Abstract: Limitations imposed on species ranges by the climatic, ecological, and physiological effects of elevation are important determinants of extinction risk. We modeled the effects of elevational limits on the extinction risk of landbirds, 87% of all bird species. Elevational limitation of range size explained 97% of the variation in the probability of being in a World Conservation Union category of extinction risk. Our model that combined elevational ranges, four Millennium Assessment habitat-loss scenarios, and an intermediate estimate of surface warming of 2.8◦ C, projected a best guess of 400–550 landbird extinctions, and that approximately 2150 additional species would be at risk of extinction by 2100. For Western Hemisphere landbirds, intermediate extinction estimates based on climate-induced changes in actual distributions ranged from 1.3% (1.1◦ C warming) to 30.0% (6.4◦ C warming) of these species. Worldwide, every degree of warming projected a nonlinear increase in bird extinctions of about 100–500 species. Only 21% of the species predicted to become extinct in our scenarios are currently considered threatened with extinction. Different habitat-loss and surface-warming scenarios predicted substantially different futures for landbird species. To improve the precision of climate-induced extinction estimates, there is an urgent need for high-resolution measurements of shifts in the elevational ranges of species. -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

BRAZIL Rio Aripuaña Mammal Expedition Oct 3Rd – Oct 16Th 2019

BRAZIL Rio Aripuaña Mammal Expedition rd th Oct 3 – Oct 16 2019 Stefan Lithner White-and-gold Marmoset Photo Stefan © Lithner This trip Was arranged by Fieldguides Birding Tours www.fieldguides.com as a mammal tour with special focus on Dwarf Manatee, bats and primates, but birds encountered were also noticed. A Fieldgjuides trip-report is available on https://fieldguides.com/triplistsSUBMIT/grm19p.html. Trip conductors were Micah Riegner with special support by Jon Hall USA, Fiona Reid, Canada, and Marcello Brazil for Bats Participants: Cherryl Antonucci USA, Jon Hall USA, Patrick Hall USA, Morten Joergensen Denmark, Stefan Lithner, Sweden, Keith Millar U.K., Fiona Reid, Canada, Mike Richardson U.K,. Micah Riegner USA, Martin Royle U.K., Lynda Sharpe Australia, Mozomi Takeyabu Denmark and Sarah Winch U. K. Itinerary in short In Manaus; MUSA-tower and Tropical Hotel. Fast boat from Manaus to Novo Aripuaña; Rio Aripuaña (Oct 4th– Oct 9 th). From Novo Aripuaña up stream Rio Aripuaña and then downstream, passing and/or making shorter expeditions; Novo Olinda, Prainha, Boca do Juma, area around Novo Olinda 1 Rio Madeira (Oct 10 th – Oct 13th), passing and/or making shorter expeditions Matamata, Igarape Lucy. Then onto Rio Amazonas (Oct 14 th – Oct 16 th) where we stopped at Miracaueira, Ilha Grande, on Rio Negro; Ariau and back to Manaus. Brief indication of areas we visited. The trip officially started by dinner in Manaus in the evening of Oct 3rd, but for people present in Manaus prior to that were offered to visit the MUSA-tower about 20 minutes ride by taxi from the hotel and Tropic Hotel, Manaus even closer. -

Human Impacts on the Rates of Recent, Present, and Future Bird Extinctions

Human impacts on the rates of recent, present, and future bird extinctions Stuart Pimm*†, Peter Raven†‡, Alan Peterson§, Çag˘anH.S¸ ekerciog˘lu¶, and Paul R. Ehrlich¶ *Nicholas School of the Environment and Earth Sciences, Duke University, Box 90328, Durham, NC 27708; ‡Missouri Botanical Garden, P.O. Box 299, St. Louis, MO 63166; §P.O. Box 1999, Walla Walla, WA 99362; and ¶Center for Conservation Biology, Department of Biological Sciences, Stanford University, 371 Serra Mall, Stanford, CA 94305-5020 Contributed by Peter Raven, June 4, 2006 Unqualified, the statement that Ϸ1.3% of the Ϸ10,000 presently ‘‘missing in action,’’ not recently recorded in its native habitat known bird species have become extinct since A.D. 1500 yields an that human actions have largely destroyed. This assumption estimate of Ϸ26 extinctions per million species per year (or 26 prevents terminating conservation efforts prematurely, even as E͞MSY). This is higher than the benchmark rate of Ϸ1E͞MSY it again underestimates the total number of extinctions. Finally, before human impacts, but is a serious underestimate. First, rapidly declining species will lose most of their populations and Polynesian expansion across the Pacific also exterminated many thus their functional roles within ecosystems long before their species well before European explorations. Second, three factors actual demise (3, 4). increase the rate: (i) The number of known extinctions before 1800 We explore the often-unstated assumptions about extinction is increasing as taxonomists describe new species from skeletal numbers to understand the various estimates. Starting before remains. (ii) One should calculate extinction rates over the years 1500 and the period of first human contact with bird species, we since taxonomists described the species. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Raccoon Island Phase B 2009 Final EA FONSI

PROPOSED MITIGATION MEASURES The following mitigation measures are proposed to reduce or eliminate environmental risks associated with the proposed action (herein referred to as the “Project”). Mitigation measures in the form of terms and conditions are added to the negotiated agreement and are shall be considered enforceable as part of the agreement. Application of terms and conditions will be individually considered by the Director or Associate Director of the MMS. Minor modifications to the proposed mitigation measures may be made during the noncompetitive negotiated leasing process if comments indicate changes are necessary or if conditions warrant. Plans and Performance Requirements The NRCS will provide the MMS with a copy of the Project’s “Construction Solicitation and Specifications Plan” (herein referred to as the “Plan”). No activity or operation, authorized by the negotiated agreement (herein referred to as the Memorandum of Agreement or MOA), at the Raccoon Island Borrow Area shall be carried out until the MMS has determined that each activity or operation described in the Plan will be conducted in a manner that is in compliance with the provisions and requirements of the MOA. The preferred method of conveying sediment from the Raccoon Island Borrow Area involves the use of a hydraulic cutterhead dredge and scows. Any modifications to the Plan that may affect the project area, including the use of submerged or floated pipelines to convey sediment, must be approved by the MMS prior to implementation of the modification. The NRCS will ensure that all operations at the Raccoon Island Borrow Area shall be conducted in accordance with the final approved Plan and all terms and conditions in this MOA, as well as all applicable regulations, orders, guidelines, and directives specified or referenced herein.