WWII Bataan Rescue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

BEST PRACTICES BEST European Union

BEST PRACTICES NON-STATE ACTORS AND LOCAL AUTHORITIES IN DEVELOPMENT – ACTIONS IN PARTNER COUNTRIES (MULTI-COUNTRY) FOR NON-STATE ACTORS Best Practices on Local Governance in Urban Public Service Delivery in Southeast-Asia www.DELGOSEA.eu DELGOSEA LOCAL GOVERNMENT DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION This project is A project implemented by the consortium: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Thailand Environment Institute (TEI), Local Government Development co-funded by the Foundation Inc. (LOGODEF), United Cities and Local Governments for Asia and Pacific (UCLG-ASPAC), Association of Indonesian Regency Governments European Union. (APKASI), Association of Cities of Vietnam (ACVN), and National League of Communes/Sangkats of the Kingdom of Cambodia (NLC/S). www.DELGOSEA.eu The Partnership for Democratic Local Governance in Southeast Asia (DELGOSEA) was launched in March 2010 and is co-funded by the European Union and the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) of Germany through the German Ministry of Development Cooperation. DELGOSEA aims to create a network of cities and municipalities to implement transnational local governance best practices replication across partner countries: Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. It supports the role of Local Government Associations (LGAs) in providing and assisting the transfer and sustainability of local governance best practices replication by local governments. Most importantly, through the exchange of best practices in the region, DELGOSEA intends to contribute to the improvement of living conditions -

Filipino Guerilla Resistance to Japanese Invasion in World War II Colin Minor Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Legacy Volume 15 | Issue 1 Article 5 Filipino Guerilla Resistance to Japanese Invasion in World War II Colin Minor Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/legacy Recommended Citation Minor, Colin () "Filipino Guerilla Resistance to Japanese Invasion in World War II," Legacy: Vol. 15 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/legacy/vol15/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Legacy by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Colin Minor Filipino Guerilla Resistance to Japanese Invasion in World War II At approximately 8:00 pm on March 11, 1942, General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the United States Army Forces in the Far East, along with his family, advisors, and senior officers, left the Philippine island of Corregidor on four Unites States Navy PT (Patrol Torpedo) boats bound for Australia. While MacArthur would have preferred to have remained with his troops in the Philippines, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Army Chief of Staff George Marshall foresaw the inevitable fall of Bataan and the Filipino capital of Manila and ordered him to evacuate. MacArthur explained upon his arrival in Terowie, Australia in his now famous speech, The President of the United States ordered me to break through the Japanese lines and proceed from Corregidor to Australia for the purpose, as I understand it, of organizing the American offensive against Japan, a primary objective of which is the relief of the Philippines. -

Download Print Version (PDF)

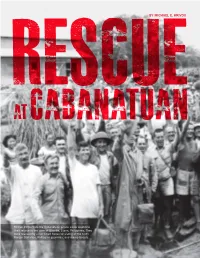

BY MICHAEL E. KRIVDO Former POWs from the Cabanatuan prison camp celebrate their rescue in the town of Guimba, Luzon, Philippines. They were rescued by a combined force consisting of the Sixth Ranger Battalion, Philippine guerrillas, and Alamo Scouts. 43 | VOL 14 NO 2 n 6 May 1942, Lieutenant General (LTG) Jonathan internees in the Philippines. They were to establish contact M. ‘Skinny’ Wainwright IV surrendered the last with them and report. This information would be used to OAmerican forces in the Philippines to the Imperial develop rescue plans.3 Japanese Army. With that capitulation more than 23,000 In late 1944, reports of the Palawan POW Camp American servicemen and women, along with 12,000 Massacre traveled quickly to SWPA (see article in previous Filipino Scouts, and 21,000 soldiers of the Philippine issue). The initial information came from the guerrillas Commonwealth Army became prisoners of war (POWs).1 who assisted survivors after escaping. The horrific details To add to the misfortune, about 20,000 American citizens, prompted SWPA to dispatch amphibian aircraft to recover many of them wives and children of the soldiers posted the escapees. Once in Australia, eyewitness accounts of the to the Philippines, were also detained and placed in mass execution caused military leaders to swear to prevent internment camps where they were subjected to hardship other atrocities. Thousands of other prisoners were still for years. Tragically, of all the American prisoners in held by the Japanese, including the thousand or so still World War II, the POWs in the Philippines suffered one believed held at Cabanatuan, on Luzon Island.4 of the highest mortality rates at 40 percent. -

Call Number Title F ELEVE 11:14 F EIGHT 8 1/2 F TEN 10 F FIFTY 54 F

Mississauga Library System DVD Library - A to E 08/08 Call Number Title F ELEVE 11:14 F EIGHT 8 1/2 F TEN 10 F FIFTY 54 F THREE 300 F FOURT 1408 F NINET 1941 HINDI F NINET 1947 SF NINET 1984 F TWENT 2046 616.834 BUT "But you still look so well--" living with multiple sclerosis / X 636. 2142 F "F" is for farm do you know where the milk comes from? 914.39 GOO The "good life" in Hungary 620.5 N "N" is for nanotechnology 822.33 T7 "O" 784.54 WEI "Weird Al" Yankovic live! 747 YOU "You can do it!" home decorating series. 7 layers of design & Color courage 747 YOU "You can do it!" home decorating series. Nurturing spaces & Double duty 362.1 AND & thou shalt honor 302.23 HAT (Hate) machine 782. 42166 NSY *NSYNC Popodyssey live. F AND ...And give my love to the swallows 613.71 EIG :08 min. abs and arms CHINESE F ONE 1 litre of tears 973 TEN 10 days that unexpectedly changed America. 1 973 TEN 10 days that unexpectedly changed America. 2 973 TEN 10 days that unexpectedly changed America. 3 613.71 TEN 10 minute solution 613.71 TEN 10 minute solution carb burner 613.71 TEN 10 minute solution kickbox bootcamp. 613.71 TEN 10 minute solution Pilates 613.71 TEN 10 minute solution target toning for beginners 613. 7046 TEN 10 minute solution Yoga F TEN 10 things I hate about you F TEN 10,000 black men named George CHINESE F ONE 100 ways to murder your wife 629.13 ONE 100 years of flight J ONE 101 Dalmatians J ONE 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London adventure / 636. -

Assuming Rape: the Reproduction of Fear in American Military Female Pows William Junior Hillius a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fu

Assuming Rape: The Reproduction of Fear in American Military Female POWs William Junior Hillius A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies University of Washington 2012 Committee: Dr. Emily Noelle Ignacio Dr. David Coon Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Tacoma Table of Contents Introduction: Your Mother wears Combat Boots……………………………………..………..6 Overview………………………………………………………………….……...7 The Vulnerable White Woman……………………………………………….…..8 The Military and Women………………………………………………………..10 The Evolution of Gender and the Media………………………………………...10 Women in the Military...................................................................................…....12 POWs in General…………………………………………………………………15 Women as POWs…………………………………………………………………16 Methods and General Findings…………………………………………………...18 The Importance of Analyzing the Discourse of Rape……………………………19 The Role of the Media……………………………………………………………19 Summary of Chapters…………………………………………………………….20 Chapter I: Captured Women: A Historical Background of American Military Female POWs. 22 Overview……………………………………………………………………….….23 Guam: 10 December 1941…………………………………………………………27 Near Baguio Philippines 28 December 1941………………………………………28 Manila Philippines 03 January 1942……………………………………………….30 Corregidor Philippine 06 May 1942………………………………………………..31 Mindanao Philippines 10 May 1942………………………………………………..35 Aachen Germany 27 September 1944……………………………………………...36 The Interim Years 1946-1991………………………………………………………37 -

Transnational Bataan Memories

TRANSNATIONAL BATAAN MEMORIES: TEXT, FILM, MONUMENT, AND COMMEMORATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AMERICAN STUDIES DECEMBER 2012 By Miguel B. Llora Dissertation Committee: Robert Perkinson, Chairperson Vernadette Gonzalez William Chapman Kathy Ferguson Yuma Totani Keywords: Bataan Death March, Public History, text, film, monuments, commemoration ii Copyright by Miguel B. Llora 2012 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank all my committee members for helping me navigate through the complex yet pleasurable process of undertaking research and writing a dissertation. My PhD experience provided me the context to gain a more profound insight into the world in which I live. In the process of writing this manuscript, I also developed a deeper understanding of myself. I also deeply appreciate the assistance of several colleagues, friends, and family who are too numerous to list. I appreciate their constant support and will forever be in their debt. Thanks and peace. iv ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of the politics of historical commemoration relating to the Bataan Death March. I began by looking for abandonment but instead I found struggles for visibility. To explain this diverse set of moves, this dissertation deploys a theoretical framework and a range of research methods that enables analysis of disparate subjects such as war memoirs, films, memorials, and commemorative events. Therefore, each chapter in this dissertation looks at a different yet interrelated struggle for visibility. This dissertation is unique because it gives voice to competing publics, it looks at the stakes they have in creating monuments of historical remembrance, and it acknowledges their competing reasons for producing their version of history. -

Legacy, Vol. 15, 2015

A Journal of Student Scholarship Volume 15 2015 A Publication of the Sigma Kappa Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta & the Southern Illinois University Carbondale History Department LEGACY Volume 15 2015 A Journal of Student Scholarship Editorial Staff Lu Li Joseph Sramek John Stewart Gray Whaley Faculty Editor Hale Yılmaz The editorial staff would like to thank all those who supported this issue of Legacy, especially the SIU Undergradute Student Government, Phi Alpha Theta, SIU Department of History faculty and staff, our history alumni, Dr. Jonathan Wiesen, our department chair, Dr. Kay J. Carr, the students who submitted papers, and their faculty mentors, Drs. Jonathan Bean, Holly Hurlburt, Gray Whaley, and Hale Yılmaz. A publication of the Sigma Kappa Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta & the History Department Southern Illinois University Carbondale history.siu.edu © 2015 Department of History, Southern Illinois University All rights reserved Photographs in “Kagawa’s English Voice: Helen Faville Topping Bridges the Cultural Gap Between East and West in Spiritual and Economic Affairs,” from Helen Faville Topping papers, Special Collections Research Center, Morris Library, Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Photograph Striped Bathing Suit in “Dawn of the New Women in Sports, Fashion, and Employment: Challenging Gender Roles in the Weimar Republic,” from bpk, Berlin/German Historical Institute, Washington, D.C./Ernst Schneider/Art Resource, New York, NY. LEGACY Volume 15 2015 A Journal of Student Scholarship Table of Contents Kagawa’s English Voice: Helen Faville Topping Bridges the Cultural Gap Between East and West in Spiritual and Economic Affairs Lauren Austin ................................................................................... 1 Dawn of the New Women in Sports, Fashion, and Employment: Challenging Gender Roles in the Weimar Republic Joshua Adair .................................................................................. -

Call Number Title

Mississauga Library System BOOKS ON DVD - A TO F Revised March 2009 CALL NUMBER TITLE F ELEVE 11:14 F EIGHT 8 1/2 F TEN 10 F TWENT 21 F FIFTY 54 F THREE 300 F FOURT 1408 F NINET 1941 HINDI F NINET 1947 SF NINET 1984 F TWENT 2046 613.71 EIG :08 min. abs and arms CHINESE F ONE 1 litre of tears 973 TEN 10 days that unexpectedly changed America. 1 973 TEN 10 days that unexpectedly changed America. 2 973 TEN 10 days that unexpectedly changed America. 3 613.71 TEN 10 minute solution 613.71 TEN 10 minute solution carb burner 613.71 TEN 10 minute solution kickbox bootcamp. 613.71 TEN 10 minute solution Pilates 613.71 TEN 10 minute solution target toning for beginners 613. 7046 TEN 10 minute solution Yoga F TEN 10 things I hate about you F TEN 10,000 BC F TEN 10,000 black men named George CHINESE F ONE 100 ways to murder your wife 629.13 ONE 100 years of flight 629.222 ONE 100 years of the automobile J ONE 101 Dalmatians J ONE 101 Dalmatians [live action] J ONE 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London adventure / 636. 1083 ONE 101 horsekeeping tips J ONE 102 dalmatians F TENTH The 10th kingdom 333.72 ELE The 11th hour 973.931 ELE The 11th of September Moyers in conversation. F TWELV 12 and holding F TWELV 12 angry men J TWELV The 12 dogs of Christmas SF TWELV 12 monkeys 613. 7148 TWE 12 qigong treasures for beginners FRENCH J DOUZE Les 12 travaux d'Asterix F TWELV 12:08 east of Bucharest X 513.5 ONE 123 count with me 649.64 ONE 1-2-3 magic managing difficult behavior in children 2-12. -

Segunda Guerra Mundial 1 Segunda Guerra Mundial

Segunda Guerra Mundial 1 Segunda Guerra Mundial Segunda Guerra Mundial Sentido horário, de cima para a esquerda: Forças chinesas na Batalha de Wanjialing; forças australianas durante a Primeira Batalha de El Alamein; aviões alemães Stuka na Frente Oriental; forças navais estadunidenses no Golfo de Lingayen; Wilhelm Keitel assinando a Rendição Alemã; tropas soviéticas durante a Batalha de Stalingrado. Data 1 de setembro de 1939- 2 de setembro de 1945 Local Europa, Oceano Atlântico, África, Médio Oriente, Sueste asiático e Oceano Pacífico Desfecho Vitória Aliada • Criação da Organização das Nações Unidas • Criação do Estado de Israel • Estabelecimento de duas superpotências, Estados Unidos e União Soviética, iniciando-se mais tarde a Guerra Fria. Intervenientes Aliados • Reino Unido • França • União Soviética • Estados Unidos • República da China • Polônia • Canadá • Austrália • Nova Zelândia • Iugoslávia • África do Sul Segunda Guerra Mundial 2 • Nepal • Dinamarca • Noruega • Países Baixos • Bélgica • Luxemburgo • Grécia • Brasil • outros Principais líderes Líderes Aliados • Winston Churchill • Joseph Stalin • Franklin Delano Roosevelt • outros Vítimas Soldados: mais de 16 milhões Cidadãos: mais de 45 milhões Total: mais de 61 milhões ...detalhesEixo • Alemanha • Império do Japão • Reino de Itália • Romênia • Hungria • Bulgária Co-intervenientes • Finlândia • Tailândia • Iraque Fantoches • Eslováquia • Croácia • Albânia • Manchukuo • outros Líderes do Eixo • Adolf Hitler • Hirohito • Benito Mussolini • outros Soldados: mais de 8 milhões Segunda Guerra Mundial 3 Cidadãos: mais de 4 milhões Total: mais de 12 milhões ...detalhes A Segunda Guerra Mundial ou II Guerra Mundial foi um conflito militar global que durou de 1939 a 1945, envolvendo a maioria das nações do mundo – incluindo todas as grandes potências – organizadas em duas alianças militares opostas: os Aliados e o Eixo. -

An Analysis of Prisoners of War Survival Narratives

“ANY ONE OF THE PRISONERS WOULD HAVE BEEN WILLING TO DIE FOR HIS COUNTRY”: AN ANALYSIS OF PRISONERS OF WAR SURVIVAL NARRATIVES By Emily Jean Koruda A Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Communication of Boston College May 2010 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................... 2 ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................ 4 CHAPTER ONE .................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER TWO................................................................................................... 7 HISTORICAL CONTEXT: IN THE TRENCHES................................................... 7 World War II ............................................................................................ 7 The Vietnam War ................................................................................... 12 CHAPTER THREE ............................................................................................ 18 REVIEW OF LITERATURE .......................................................................... 18 CHAPTER FOUR ............................................................................................... 26 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................... 26 ARTIFACT CHOICE -

Jimmy Carter Man from Plains

Presents A Jonathan Demme Picture JIMMY CARTER MAN FROM PLAINS Official Selection 2007 Toronto International Film Festival (126 mins,USA, 2007) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html Director’s Statement I have always held President Carter in high esteem, so I leapt at the opportunity to do a documentary portrait of him. I chose the book tour of Palestine Peace Not Apartheid as the backbone of the documentary before reading the book. I knew that with the kind of subject matter promised by the title, there would probably be a lot of fireworks on that journey. I love how his un-self-censored behavior and attitudes help reveal how authentic and deep President Carter's faith-based motivation really is - and how terrifically complicated he is as a human being, with such an active sense of humor, an encyclopedic knowledge of a seeming endless array of subjects - and how super- sensitive yet bold, feisty and obstinate he can be at times - and that he reveals how a devoted, adoring husband like him fits so organically with the fellow who "loves the ladies." Every time I see this film, President Carter makes me believe that - as frightening and appalling as so many things are in the world today - that there is nevertheless a very real possibility for peace and better lives for future generations if we strive to somehow get along and if we aspire to defining the upside of being human.