Reflections on the Needle: Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking, 44 Val

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications Summer 1996 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Roberta M. Harding University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Repository Citation Harding, Roberta M., "Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment" (1996). Law Faculty Scholarly Articles. 563. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Notes/Citation Information Robert M. Harding, Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment, 30 U.S.F. L. Rev. 1167 (1996). This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment By ROBERTA M. HARDING* FILMMAKING HAS EXISTED since the late 1890s. 1 Capital punish- ment has existed even longer.2 With more than 3,000 individuals lan- guishing on the nation's death rows3 and more than 300 executions occurring since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976,4 capital pun- ishment has become one of modem society's most controversial issues. The cinematic world has not been immune from this debate. -

“Dead Man Walking” by Sister Helen Prejean

“Dead man walking” by Sister Helen Prejean At first I would like to say a few words about the authors biography and after that I will come to the story of the book which is completely different from the story of the film and in the end we will see a little excerpt of the German version of the film Sister Helen Prejean Sister Helen Prejean, the Author of dead man walking, was born on the 21st of April in 1939, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and has lived and worked in Louisiana all her life. She joined the Sisters of St. Joseph in 1957. Her ministries have included teaching junior and senior high students. Involvement with poor inner city residents in the St. Thomas Housing Project in New Orleans in 1981 led her to prison ministry where she counseled death row inmates in the Louisiana State Penitentiary. She has accompanied three men to the electric chair and witnessed their deaths. Since then, she has devoted her energies to the education of the public about the death penalty by lecturing, organizing and writing. She also has befriended murder victims' families and she helped to found "Survive" a victims advocacy group in New Orleans. Currently, she continues her ministry to death row inmates and murder victims'. She also is a member of Amnesty International. The story In 1977, Patrick and his Brother Eddie had abducted a teenage couple, Loretta Bourque and David Le Blanc, from a lovers’ lane, raped the girl, forced them to lie face down and shot them into the head. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

And Then One Night… the Making of DEAD MAN WALKING

And Then One Night… The Making of DEAD MAN WALKING Complete program transcript Prologue: Sister Helen and Joe Confession scene. SISTER HELEN I got an invitation to write to somebody on death row and then I walked with him to the electric chair on the night of April the fifth, 1984. And once your boat gets in those waters, then I became a witness. Louisiana TV footage of Sister Helen at Hope House NARRATION: “Dead Man Walking” follows the journey of a Louisiana nun, Sister Helen Prejean, to the heart of the death penalty controversy. We see Sister Helen visiting with prisoners at Angola. NARRATION: Her groundbreaking work with death row inmates inspired her to write a book she called “Dead Man Walking.” Her story inspired a powerful feature film… Clip of the film: Dead Man Walking NARRATION: …and now, an opera…. Clip from the opera “Dead Man Walking” SISTER HELEN I never dreamed I was going to get with death row inmates. I got involved with poor people and then learned there was a direct track from being poor in this country and going to prison and going to death row. NARRATION: As the opera began to take shape, the death penalty debate claimed center stage in the news. Gov. George Ryan, IL: I now favor a moratorium because I have grave concerns about our state’s shameful record of convicting innocent people and putting them on death row. Gov. George W. Bush, TX: I’ve been asked this question a lot ever since Governor Ryan declared a moratorium in Illinois. -

The Journey of Dead Man Walking

Sacred Heart University Review Volume 20 Issue 1 Sacred Heart University Review, Volume XX, Article 1 Numbers 1 & 2, Fall 1999/ Spring 2000 2000 The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Helen Prejean Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview Recommended Citation Prejean, Helen (2000) "The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking," Sacred Heart University Review: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the SHU Press Publications at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sacred Heart University Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Cover Page Footnote This is a lightly edited transcription of the talk delivered by Sister Prejean at Sacred Heart University on October 31, 2000, sponsored by the Hersher Institute for Applied Ethics and by Campus Ministry. This article is available in Sacred Heart University Review: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 Prejean: The Journey of Dead Man Walking SISTER HELEN PREJEAN, C.S.J. The Journey of Dead Man Walking I'm glad to be with you. I'm going to bring you with me on a journey, an incredible journey, really. I never thought I was going to get involved in these things, never thought I would accompany people on death row and witness the execution of five human beings, never thought I would be meeting with murder victims' families and accompanying them down the terrible trail of tears and grief and seeking of healing and wholeness, never thought I would encounter politicians, never thought I would be getting on airplanes and coming now for close to fourteen years to talk to people about the death penalty. -

Native Gardens Program

2017/18 SEASON SUBSCRIPTIONS ON SALE NOW! SPECIAL ADD-ON EVENT Photo of Jack Willis in All The Way by Stan Barouh. 202-488-3300 ORDER TODAY! ARENASTAGE.ORG NATIVE GARDENS TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Artistically Speaking 5 From the Executive Director 6 Molly Smith’s 20th Anniversary Season 9 Playwright’s Note 11 Title Page 13 Setting / Cast List / For this Production 15 Bios - Cast 17 Bios - Creative Team ARENA STAGE 23 Arena Stage Leadership 1101 Sixth Street SW Washington, DC 20024-2461 ADMINISTRATION 202-554-9066 24 Board of Trustees / Theatre Forward SALES OFFICE 202-488-3300 TTY 202-484-0247 25 Full Circle Society arenastage.org © 2017 Arena Stage. 26 Thank You – The Annual Fund All editorial and advertising material is fully protected and must not be reproduced in any manner without 29 Thank You – Institutional Donors written permission. Native Gardens 30 Theater Staff Program Book Published September 15, 2017 Cover Illustration by Nigel Buchanan Program Book Staff Anna Russell, Director of Publications Shawn Helm, Graphic Designer ARTISTICALLY SPEAKING I have just come back from a rejuvenating visit to our cabin in Alaska, and I’m excited to continue this season with Karen Zacarias’ Native Gardens after John Strand’s The Originalist. In Alaska we literally share a back yard with bears (yes, grizzly bears, the big brown ones) and I witnessed them fishing for spawning salmon, greedily mowing down bushes of blueberries and eating sedge grass. But that was nature … not our country. The events of the last few weeks have been horrifying to watch and hear. -

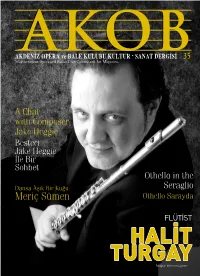

An Interview with Jake Heggie

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean. -

BIG COKE BUST 86 Delta 88 2 Door *9995 Difference 86 Bonneville 4 Door *6995 Late Morning News Conference

20— MANCHESTER HERALD, Friday, Sept. 29„ 1989 iCARS CARS CARS ICARS I q TI cars FOR SALE FOR SALE IQII CARS L i L I FOR SALE FOR SALE E l l FOR SALE I ^ U fOR SALE BUICK Skylark 1980 - 2 1984 HONDA Accord - 1986 MERCURY Grand SUBARU 1982-GL, red, 5 door, excellent condi Immaculate, 4 door, 5 speed, olr, sunroof. tion, 52,000 miles, $1500. speed, am/fm cassette, Marquis-4 door, white, loaded plus sunroof. 140K miles. $600/best 643-1783.______________ low miles, 1 owner, sun O n e owner. New offer. Must sell. 645- PONTIAC 74 Wagon ^ roof, cruise, must see. brakes. Complete new 0480. 455cc, V8, auto, air 646-3165._____________ tune up, lifetime conditioner, power 1978 DATSUN 810 - 240z window/locks, work- shocks. Coll Jim McCo- engine, good condi vonogh. 649-3800. house. $400 or best tion. $1050. 643-4971 of- TRUCKS/VANS otter. 646-6212. CHEVY Caprice Classic ter 7pm._____________ 1986 - 4 door, mint, FOR SALE PLYMOUTH 1985 Ho 63,000 highway miles, CARDINAL rizon - 4 door, 5 speed, $7000. 291-8910. GMC 1988 4x4 loaded om-fm radio. $1200.647- pickup with deluxe BUICK, INC. 9758 otter 5pm._______ cop. Excellent condi 1986 HONDA XR-250 In tion. $11,750. GMC 1988 BUICK 1979 Skvhowk - 2 storage. Mint, mint 1988ChevS-10Ext,Cab $12,995 pickup with cop. Excel door hatch, good con- condition. 175 original 1988 Pont Grand Am $6,690 lent condition. $11,250. dltlon, standard. miles, legal street re 643-5614 ask for Roy or PERIENCE 1988 Buick LaSabre $11,980 $700/best offer. -

Dead Man Walking-An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States

NYLS Journal of Human Rights Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 8 Fall 1994 DEAD MAN WALKING-AN EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES Ronald J. Tabak Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_human_rights Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Tabak, Ronald J. (1994) "DEAD MAN WALKING-AN EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES," NYLS Journal of Human Rights: Vol. 12 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_human_rights/vol12/iss1/8 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of Human Rights by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. DEAD MAN WALKING-AN EYEWrTNESS ACCOUNT OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES. By Sister Helen Prejean, C.S.J. New York Random House (1993). Pp. 278. $21.00. Reviewed by Ronald J. Tabak" December of 1994, when I wrote this review of Sister Helen Prejean's fascinating and sobering book, Dead Man Walking-An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States,1 was ten years to the month of the execution of my client, Robert Lee Willie. It was also, not coincidentally, ten years to the month in which I first encountered Sister Helen. I had represented Willie in seeking certiorari from the United States Supreme Court in late 1983 to review his conviction and sentence, which was all I had originally agreed to do on his behalf. But when I learned that if I did not continue to represent him, there would likely be no one to represent him in his first state post-conviction and federal habeas corpus proceedings, I felt I could not walk away. -

Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking, 44 Val

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 44 Number 1 Fall 2009 pp.37-68 Fall 2009 Reflections on the Needle: oe,P Baze, Dead Man Walking Robert Batey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert Batey, Reflections on the Needle: Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking, 44 Val. U. L. Rev. 37 (2009). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol44/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Batey: Reflections on the Needle: Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking REFLECTIONS ON THE NEEDLE: POE, BAZE, DEAD MAN WALKING Robert Batey* The goal of most of the “Law and . .” movements is to bring the perspective of the humanities to legal issues. Literature and film, for examples, can cause one to envision such issues afresh. Sometimes this viewing from a new angle is premeditated, but sometimes it sneaks up on you. During a recent fall semester my colleague, Kristen Adams, asked that I speak to Stetson’s Honors Colloquium1 on a law and literature topic.2 The only date we could work out was Halloween, and so Professor Adams and I laughingly agreed that Edgar Allan Poe would be an appropriate choice. Dipping into Poe’s stories (all of which seem to be online), I immediately sensed their resonance with the law of capital punishment, another of my academic interests.3 The Fall of the House of Usher seemed filled with images of the death house. -

FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini

Pat McCorkle, CSA Jeffrey Dreisbach, Casting Partner Katja Zarolinski, CSA Kristen Kittel, Casting Assistant FILM SENIOR MOMENT (Goff Productions) Director: Giorgio Serafini. Starring: William Shatner, Christopher Lloyd, Jean Smart. THE MURPHYS (Independent Feature; Producer(s): The Murphy's LLC). Director: Kaitlan McGlaughlin. BERNARD & HUEY (In production. Independent Feature; Producer(s): Dan Mervish/Bernie Stein). Director: Dan Mervish. AFTER THE SUN FELL (Post Production. Independent feature; Producer(s): Joanna Bayless). Director: Tony Glazer. Starring: Lance Henriksen, Chasty Ballesteros, Danny Pudi. FAIR MARKET VALUE (Post Production. Feature ; Producer(s): Judy San Romain). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Jerry Adler, D.C. Anderson, Michael J. Arbouet. YEAR BY THE SEA (Festival circuit. Feature; Producer(s): Montabella Productions ). Director: Alexander Janko. Starring: Karen Allen, Yannick Bisson, Michael Cristofer. CHILD OF GRACE (Lifetime Network Feature; Producer(s): Empathy + Pictures/Sternamn Productions). Director: Ian McCrudden. Starring: Ted Lavine, Maggy Elizabeth Jones, Michael Hildreth. POLICE STATE (Independent Feature; Producer(s): Edwin Mejia\Vlad Yudin). Director: Kevin Arbouet. Starring: Sean Young, Seth Gilliam, Christina Brucato. MY MAN IS A LOSER (Lionsgate, Step One Entertainment; Producer(s): Step One of Many/Imprint). Director: Mike Young. Starring: John Stamos, Tika Sumpter, Michael Rapaport. PREMIUM RUSH (Columbia Pictures; Producer(s): Pariah). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. JUNCTION (Movie Ranch; Producer(s): Choice Films). Director: David Koepp . Starring: Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Jamie Chung, Michael Shannon. GHOST TOWN* (Paramount Pictures; Producer(s): Dreamworks SKG). Director: David Koepp. Starring: Ricky Gervais, Tea Leoni, Greg Kinnear. WAR EAGLE (Empire Film; Producer(s): Downstream Productions). Director: Robert Milazzo. Starring: Brian Dennehy, Mary Kay Place, Mare Winningham. -

'88 Buick Blowout at Dealer Invoice!!

24 — MANCHESTER HERALD, Friday. Jan 27, 1989 I HOMES BUSINESS I ROOMS ■99 J APARTMENTS I CONDOMINIUMS VACATION I PETS AND CARS FOR SALE PROPERTY FOR RENT I J ^ I fOR RENT FOR RENT RENTALS SUPPLIES FOR SALE F IN IS H It you rself! ITALIAN 8. Pizza Restau SIN G LE Room tor rent. MANCHESTER. Twoand MANCHESTER. Very RHODE ISLAND. Matu- FR E E to good home. OLDSMOBILE Regency Builder will sell this rant. $69,900. Call office Females preferred. three bedroom apart nice two bath, two bed nuck Beach. Ocean Pure breed, Brindle Brougham , 1986, 4 Colonial home with for details. Anne Miller Convenient location. ments. References and room Condo. Pool and view, three bedroom Boxer. Three years door, V6, tope deck, lust a finished exterior Real Estate, 647-8000.Q $75 per week plus $100 security a must. Call sauna. Near 1-384. $700 J Contemporary. Fully old, house broken, loaded. 24,900 miles. and a well for $155,000. security. Call 649-9472 Joyce, 645-8201.______ per month. Call 285-’ equipped, half mile to spayed. Excellent dog. Asking $9,500. 643-8973. Plans call for 3 bed between 3:30-7, ask for M ANCH ESTER. Quality, 8884 or 633-3349. beach. 644-9639, after Coll 649-0514. rooms, 2.5 baths, first Eleanor. 1976 FORD Gronodo. RESORT heat, hot water, all 5pm. Coll 643-2711 to ploce your Needs some work. floor family room, ap- appliances Included, FINDING A cash buyer proxlmotely 1900 1^01 p r o p e r ty od. Good V8 engine.