Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking, 44 Val

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death Penalty: History, Exonerations, and Moratoria

THEMES & DEBATES The Death Penalty: History, Exonerations, and Moratoria Martin Donohoe, MD Today’s topic is the death penalty. I will discuss is released to suffocate the prisoner, was introduced multiple areas related to the death penalty, including in 1924. its history; major Supreme Court decisions; contem- In 2001, the Georgia Supreme Court ruled that porary status; racial differences; errors and exonera- electrocution violates the Constitution’s prohibition tions; public opinion; moratoria; and ethics and mo- against cruel and unusual punishment, stating that it rality. I will also refute common myths, including causes “excruciating pain…cooked brains and blis- those that posit that the death penalty is humane; tered bodies.” In 2008, Nebraska became the last equally applied across the states; used largely by remaining state to agree. “Western” countries; color-blind; infallible; a deter- In the 1970s and 1980s, anesthesiologist Stanley rent to crime; and moral. Deutsch and pathologist Jay Chapman developed From ancient times through the 18th Century, techniques of lethal injection, along with a death methods of execution included crucifixion, crushing cocktail consisting of 3 drugs designed to “humane- by elephant, keelhauling, the guillotine, and, non- ly” kill inmates: an anesthetic, a paralyzing agent, metaphorically, death by a thousand cuts. and potassium chloride (which stops the heart beat- Between 1608 and 1972, there were an estimated ing). Lethal injection was first used in Texas in 1982 15,000 state-sanctioned executions in the colonies, and is now the predominant mode of execution in and later the United States. this country. Executions in the 19th and much of the 20th Cen- Death by lethal injection cannot be considered tury were carried out by hanging, known as lynching humane. -

Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications Summer 1996 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Roberta M. Harding University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Repository Citation Harding, Roberta M., "Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment" (1996). Law Faculty Scholarly Articles. 563. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Notes/Citation Information Robert M. Harding, Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment, 30 U.S.F. L. Rev. 1167 (1996). This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment By ROBERTA M. HARDING* FILMMAKING HAS EXISTED since the late 1890s. 1 Capital punish- ment has existed even longer.2 With more than 3,000 individuals lan- guishing on the nation's death rows3 and more than 300 executions occurring since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976,4 capital pun- ishment has become one of modem society's most controversial issues. The cinematic world has not been immune from this debate. -

“Dead Man Walking” by Sister Helen Prejean

“Dead man walking” by Sister Helen Prejean At first I would like to say a few words about the authors biography and after that I will come to the story of the book which is completely different from the story of the film and in the end we will see a little excerpt of the German version of the film Sister Helen Prejean Sister Helen Prejean, the Author of dead man walking, was born on the 21st of April in 1939, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and has lived and worked in Louisiana all her life. She joined the Sisters of St. Joseph in 1957. Her ministries have included teaching junior and senior high students. Involvement with poor inner city residents in the St. Thomas Housing Project in New Orleans in 1981 led her to prison ministry where she counseled death row inmates in the Louisiana State Penitentiary. She has accompanied three men to the electric chair and witnessed their deaths. Since then, she has devoted her energies to the education of the public about the death penalty by lecturing, organizing and writing. She also has befriended murder victims' families and she helped to found "Survive" a victims advocacy group in New Orleans. Currently, she continues her ministry to death row inmates and murder victims'. She also is a member of Amnesty International. The story In 1977, Patrick and his Brother Eddie had abducted a teenage couple, Loretta Bourque and David Le Blanc, from a lovers’ lane, raped the girl, forced them to lie face down and shot them into the head. -

Antigone and Literary Criticism

Summer Reading English II Honors Antigone and Literary Criticism English II Honors students are required to complete the posted reading over the summer and come to class prepared to discuss the critical issues raised in the essays about the play Antigone. A suggested reading order is as follows: “Antigone Synopsis” “Introduction to Antigone” Antigone (text provided in .pdf form) “Antigone Commentary” It is recommended that students print out hard copies of the three critical essays for note-taking purposes; a hard copy of the complete text of Antigone will be provided the first week of class, so there is no need to print the entire play. Student Goals: to familiarize yourself with Antigone, Greek Drama, and literary criticism prior to the first day of class; to demonstrate critical thinking and writing skills the first week of class. See you in August!. Mr. Gordon 5/13/2019 History - Print - Introduction to <em>Antigone</em> Bloom's Literature Introduction to Antigone I. Author and Background It seems that in March, 441 B.C., the Antigone made Sophocles famous. The poet, fifty-five years old, had now produced thirty-two plays; because of this one, tradition relates, the people of Athens elected him, the next year, to high office. We hear he shared the command of the second fleet sent to Samos. When the people of Samos failed to support the government just established for them by forty Athenian ships, Athens sent a fleet of sixty ships to restore democracy and remove the rebels. The Aegean then was an Athenian sea. Pericles, the great political leader and advocate of firm alliance, was first in command. -

Omnes Vulnerant, Postuma Necat; All the Hours Wound, the Last One Kills: the Lengthy Stay on Death Row in America

Missouri Law Review Volume 80 Issue 3 Summer 2015 Article 13 Summer 2015 Omnes Vulnerant, Postuma Necat; All the Hours Wound, the Last One Kills: The Lengthy Stay on Death Row in America Mary Elizabeth Tongue Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mary Elizabeth Tongue, Omnes Vulnerant, Postuma Necat; All the Hours Wound, the Last One Kills: The Lengthy Stay on Death Row in America, 80 MO. L. REV. (2015) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol80/iss3/13 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tongue: Omnes Vulnerant, Postuma Necat; LAW SUMMARY Omnes Vulnerant, Postuma Necat; All the Hours Wound, the Last One Kills: The Lengthy Stay on Death Row in America MEGAN ELIZABETH TONGUE* I. INTRODUCTION The Bureau of Justice Statistics has compiled statistical analyses show- ing that the average amount of time an inmate spends on death row has stead- ily increased over the past thirty years.1 In fact, the shortest average amount of time an inmate spent on death row during that time period was seventy-one months in 1985, or roughly six years, with the longest amount of time being 198 months, or sixteen and one half years, in 2012.2 This means that -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

And Then One Night… the Making of DEAD MAN WALKING

And Then One Night… The Making of DEAD MAN WALKING Complete program transcript Prologue: Sister Helen and Joe Confession scene. SISTER HELEN I got an invitation to write to somebody on death row and then I walked with him to the electric chair on the night of April the fifth, 1984. And once your boat gets in those waters, then I became a witness. Louisiana TV footage of Sister Helen at Hope House NARRATION: “Dead Man Walking” follows the journey of a Louisiana nun, Sister Helen Prejean, to the heart of the death penalty controversy. We see Sister Helen visiting with prisoners at Angola. NARRATION: Her groundbreaking work with death row inmates inspired her to write a book she called “Dead Man Walking.” Her story inspired a powerful feature film… Clip of the film: Dead Man Walking NARRATION: …and now, an opera…. Clip from the opera “Dead Man Walking” SISTER HELEN I never dreamed I was going to get with death row inmates. I got involved with poor people and then learned there was a direct track from being poor in this country and going to prison and going to death row. NARRATION: As the opera began to take shape, the death penalty debate claimed center stage in the news. Gov. George Ryan, IL: I now favor a moratorium because I have grave concerns about our state’s shameful record of convicting innocent people and putting them on death row. Gov. George W. Bush, TX: I’ve been asked this question a lot ever since Governor Ryan declared a moratorium in Illinois. -

"Slow Dance on the Killing Ground": the Willie Francis Case Revisited

DePaul Law Review Volume 32 Issue 1 Fall 1982 Article 2 "Slow Dance on the Killing Ground": The Willie Francis Case Revisited Arthur S. Miller Jeffrey H. Bowman Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation Arthur S. Miller & Jeffrey H. Bowman, "Slow Dance on the Killing Ground": The Willie Francis Case Revisited, 32 DePaul L. Rev. 1 (1982) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol32/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "SLOW DANCE ON THE KILLING GROUND":t THE WILLIE FRANCIS CASE REVISITED tt Arthur S. Miller* and Jeffrey H. Bowman** The time is past in the history of the world when any living man or body of men can be set on a pedestal and decorated with a halo. FELIX FRANKFURTER*** The time is 1946. The place: rural Louisiana. A slim black teenager named Willie Francis was nervous. Understandably so. The State of Louisiana was getting ready to kill him by causing a current of electricity to pass through his shackled body. Strapped in a portable electric chair, a hood was placed over his head, and the electric chair attendant threw the switch, saying in a harsh voice "Goodbye, Willie." The chair didn't work properly; the port- able generator failed to provide enough voltage. Electricity passed through Willie's body, but not enough to kill him. -

The Journey of Dead Man Walking

Sacred Heart University Review Volume 20 Issue 1 Sacred Heart University Review, Volume XX, Article 1 Numbers 1 & 2, Fall 1999/ Spring 2000 2000 The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Helen Prejean Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview Recommended Citation Prejean, Helen (2000) "The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking," Sacred Heart University Review: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the SHU Press Publications at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sacred Heart University Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Cover Page Footnote This is a lightly edited transcription of the talk delivered by Sister Prejean at Sacred Heart University on October 31, 2000, sponsored by the Hersher Institute for Applied Ethics and by Campus Ministry. This article is available in Sacred Heart University Review: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 Prejean: The Journey of Dead Man Walking SISTER HELEN PREJEAN, C.S.J. The Journey of Dead Man Walking I'm glad to be with you. I'm going to bring you with me on a journey, an incredible journey, really. I never thought I was going to get involved in these things, never thought I would accompany people on death row and witness the execution of five human beings, never thought I would be meeting with murder victims' families and accompanying them down the terrible trail of tears and grief and seeking of healing and wholeness, never thought I would encounter politicians, never thought I would be getting on airplanes and coming now for close to fourteen years to talk to people about the death penalty. -

Native Gardens Program

2017/18 SEASON SUBSCRIPTIONS ON SALE NOW! SPECIAL ADD-ON EVENT Photo of Jack Willis in All The Way by Stan Barouh. 202-488-3300 ORDER TODAY! ARENASTAGE.ORG NATIVE GARDENS TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 Artistically Speaking 5 From the Executive Director 6 Molly Smith’s 20th Anniversary Season 9 Playwright’s Note 11 Title Page 13 Setting / Cast List / For this Production 15 Bios - Cast 17 Bios - Creative Team ARENA STAGE 23 Arena Stage Leadership 1101 Sixth Street SW Washington, DC 20024-2461 ADMINISTRATION 202-554-9066 24 Board of Trustees / Theatre Forward SALES OFFICE 202-488-3300 TTY 202-484-0247 25 Full Circle Society arenastage.org © 2017 Arena Stage. 26 Thank You – The Annual Fund All editorial and advertising material is fully protected and must not be reproduced in any manner without 29 Thank You – Institutional Donors written permission. Native Gardens 30 Theater Staff Program Book Published September 15, 2017 Cover Illustration by Nigel Buchanan Program Book Staff Anna Russell, Director of Publications Shawn Helm, Graphic Designer ARTISTICALLY SPEAKING I have just come back from a rejuvenating visit to our cabin in Alaska, and I’m excited to continue this season with Karen Zacarias’ Native Gardens after John Strand’s The Originalist. In Alaska we literally share a back yard with bears (yes, grizzly bears, the big brown ones) and I witnessed them fishing for spawning salmon, greedily mowing down bushes of blueberries and eating sedge grass. But that was nature … not our country. The events of the last few weeks have been horrifying to watch and hear. -

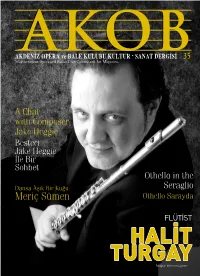

An Interview with Jake Heggie

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean. -

Buried Alive

BURIED ALIVE AN EXAMINATION INTO The Occult Causes of Apparent Death, Trance and Catalepsy BY FRANZ HARTMANN, M. D. “ The appearance of decomposition is the only reliable proof that the vital energy has departed from an organism.” — Hufhland. “ It is the glory of God to conceal a thing; but the honor of kings is to search out a matter.” — Proverbs, xxv, 2. BOSTON OCCULT PUBLISHING CO. 1895 Digitized by L.ooole Copyright, 18Q4, By F ranz Hartmann, M. D . S .J . Parkhitt 6r Co., Typography and Pressutork, Boston, U.S. A. Digitized by '- o o Q le (D edicated. TO THE PEOPLE OF THE UNITED STATES AND TO ALL MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS WHO ENJOY FREEDOM OF THOUGHT. Digitized by C . o o Q l e Digitized by L . o o Q l e PREFACE. I ASi not writing a book for the purpose of convert ing science, but for converting ignorance. I have all possible respect for the true scientists who, while utilizing the knowledge which has been arrived at dur ing the past, do not become petrified in the narrow grooves of the past, but seek for more light and more truth, independent of orthodox doctrines that have been or may still be looked upon by some as the ultimate dictates of science; but I have no regard whatever for the conceit of that class of so-called scientists, whose only wisdom consists of the dreams which they have found described in their accepted orthodox books and of the authorized theories with which they have crammed and obstructed their brains, while they refuse to open their own eyes and to look deeper into the mysteries of nature or to listen to anything that goes beyond the scope of that system which has been taught to them in their schools.