The Journey of Dead Man Walking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications Summer 1996 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Roberta M. Harding University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Repository Citation Harding, Roberta M., "Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment" (1996). Law Faculty Scholarly Articles. 563. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Notes/Citation Information Robert M. Harding, Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment, 30 U.S.F. L. Rev. 1167 (1996). This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment By ROBERTA M. HARDING* FILMMAKING HAS EXISTED since the late 1890s. 1 Capital punish- ment has existed even longer.2 With more than 3,000 individuals lan- guishing on the nation's death rows3 and more than 300 executions occurring since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976,4 capital pun- ishment has become one of modem society's most controversial issues. The cinematic world has not been immune from this debate. -

Watermark W Atermark

WATERMARK A SCHOLARLY JOURNAL PUBLISHED BY THE GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH AT CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, LONG BEACH 8 WATERMARK 8 WATERMARK SPRING 2014 Watermark accepts submissions annually between October and February. We are 8 WWW WWW dedicated to publishing original critical and theoretical essays concerned with literature of all genres and periods, as well as works representing current issues Editor ∙ in the fields of rhetoric and composition. Reviews of current works of literary Mary Sotnick criticism or theory are also welcome. Managing Editors ∙ Rusty Rust Jaime Rapp All submissions must be accompanied by a cover letter that includes the author’s ∙ name, phone number, email address, and the title of the essay or book review. All essay submissions should be approximately 12-15 pages and must be typed American Literature Editors Levon Parseghian ∙ Shouhei J. Tanaka ∙ Amy Desusa in MLA format with a standard 12 pt. font. Book reviews ought to be 750-1,000 words in length. As this journal is intended to provide a forum for emerging British Literature Editors voices, only student work will be considered for publication. Submissions will Bethany Acevedo not be returned. Please direct all questions to [email protected] and address all submissions to: Ethnic American Literature Jaime Rapp ∙ Rusty Rust ∙ Phương Lưu Department of English: Watermark California State University, Long Beach Rhetoric & Composition Editors 1250 Bellflower Boulevard Dya Cangiano Long Beach, CA 90840 Medieval & Renaissance Studies Editors Visit us -

“Dead Man Walking” by Sister Helen Prejean

“Dead man walking” by Sister Helen Prejean At first I would like to say a few words about the authors biography and after that I will come to the story of the book which is completely different from the story of the film and in the end we will see a little excerpt of the German version of the film Sister Helen Prejean Sister Helen Prejean, the Author of dead man walking, was born on the 21st of April in 1939, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and has lived and worked in Louisiana all her life. She joined the Sisters of St. Joseph in 1957. Her ministries have included teaching junior and senior high students. Involvement with poor inner city residents in the St. Thomas Housing Project in New Orleans in 1981 led her to prison ministry where she counseled death row inmates in the Louisiana State Penitentiary. She has accompanied three men to the electric chair and witnessed their deaths. Since then, she has devoted her energies to the education of the public about the death penalty by lecturing, organizing and writing. She also has befriended murder victims' families and she helped to found "Survive" a victims advocacy group in New Orleans. Currently, she continues her ministry to death row inmates and murder victims'. She also is a member of Amnesty International. The story In 1977, Patrick and his Brother Eddie had abducted a teenage couple, Loretta Bourque and David Le Blanc, from a lovers’ lane, raped the girl, forced them to lie face down and shot them into the head. -

Transforming Times As Sisters of St

Spring/Summer y Vol. 3 y no. 1 ONEThe CongregaTion of The SiSTerS of ST. JoSeph imagine Transforming Times as Sisters of St. Joseph flows from the purpose for which the congregation exists: We live and work that all people may be united with god and with one another. We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, living out of our common Spring/Summer 2011 y Vol. 3 y no. 1 tradition, witness to God’s love transforming us and our world. Recognizing that we are called to incarnate our mission and imagineONE is published twice yearly, charism in our world in fidelity to God’s call in the Gospel, we in Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter, commit ourselves to these Generous Promises through 2013. by the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph. z We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, promise to take the risk CENTRAL OFFICE to surrender our lives and resources to work for specific 3430 Rocky River Drive systemic change in collaboration with others so that the Cleveland, OH 44111-2997 Ourhungers mission of the world might be fed. (216) 252-0440 WITH SIGNIFICANT PRESENCE IN z We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, promise to recognize the reality that Earth is dying, to claim our oneness with Baton Rouge, LA Earth and to take steps now to strengthen, heal and renew Cincinnati, OH Crookston, MN the face of Earth. Detroit, MI z Kyoto, Japan We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, promise to network LaGrange Park, IL with others across the world to bring about a shift in the Minneapolis-St. -

And Then One Night… the Making of DEAD MAN WALKING

And Then One Night… The Making of DEAD MAN WALKING Complete program transcript Prologue: Sister Helen and Joe Confession scene. SISTER HELEN I got an invitation to write to somebody on death row and then I walked with him to the electric chair on the night of April the fifth, 1984. And once your boat gets in those waters, then I became a witness. Louisiana TV footage of Sister Helen at Hope House NARRATION: “Dead Man Walking” follows the journey of a Louisiana nun, Sister Helen Prejean, to the heart of the death penalty controversy. We see Sister Helen visiting with prisoners at Angola. NARRATION: Her groundbreaking work with death row inmates inspired her to write a book she called “Dead Man Walking.” Her story inspired a powerful feature film… Clip of the film: Dead Man Walking NARRATION: …and now, an opera…. Clip from the opera “Dead Man Walking” SISTER HELEN I never dreamed I was going to get with death row inmates. I got involved with poor people and then learned there was a direct track from being poor in this country and going to prison and going to death row. NARRATION: As the opera began to take shape, the death penalty debate claimed center stage in the news. Gov. George Ryan, IL: I now favor a moratorium because I have grave concerns about our state’s shameful record of convicting innocent people and putting them on death row. Gov. George W. Bush, TX: I’ve been asked this question a lot ever since Governor Ryan declared a moratorium in Illinois. -

An Interview with Jake Heggie

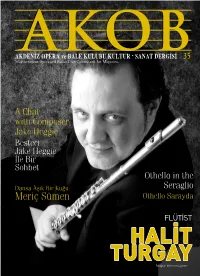

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean. -

DISTRICT AUDITIONS THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2021 the 2020 National Council Finalists Photo: Fay Fox / Met Opera

NATIONAL COUNCIL 2020–21 SEASON ARKANSAS DISTRICT AUDITIONS THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2021 The 2020 National Council Finalists photo: fay fox / met opera CAMILLE LABARRE NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS chairman The Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions program cultivates young opera CAROL E. DOMINA singers and assists in the development of their careers. The Auditions are held annually president in 39 districts and 12 regions of the United States, Canada, and Mexico—all administered MELISSA WEGNER by dedicated National Council members and volunteers. Winners of the region auditions executive director advance to compete in the national semifinals. National finalists are then selected and BRADY WALSH compete in the Grand Finals Concert. During the 2020–21 season, the auditions are being administrator held virtually via livestream. Singers compete for prize money and receive feedback from LISETTE OROPESA judges at all levels of the competition. national advisor Many of the world’s greatest singers, among them Lawrence Brownlee, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Renée Fleming, Lisette Oropesa, Eric Owens, and Frederica von Stade, have won National Semifinals the Auditions. More than 100 former auditioners appear appear on the Met roster each season. Sunday, May 9, 2021 The National Council is grateful to its donors for prizes at the national level and to the Tobin Grand Finals Concert Endowment for the Mrs. Edgar Tobin Award, given to each first-place region winner. Sunday, May 16, 2021 Support for this program is generously provided by the Charles H. Dyson National Council The Semifinals and Grand Finals are Audition Program Endowment Fund at the Metropolitan Opera. currently scheduled to take place at the Met. -

Execution Ritual : Media Representations of Execution and the Social Construction of Public Opinion Regarding the Death Penalty

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2011 Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty. Emilie Dyer 1987- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Dyer, Emilie 1987-, "Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 388. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/388 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXECUTION RITUAL: MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fullfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May, 2011 -------------------------------------------------------------- EXECUTION RITUAL : MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Brook Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Approved on April 11, 2011 by the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director (Dr. -

Billy Budd Cast Biographies

Billy Budd Cast Biographies William Burden sang George Bailey in San Francisco Opera’s West Coast premiere of Jake Heggie’s It’s a Wonderful Life in fall 2018. The American tenor made his San Francisco Opera debut in 1992 as Count Lerma in Don Carlo and has returned in roles including Laca in Jenůfa, Tom Rakewell in The Rake’s Progress and he created the roles of Dan Hill in Christopher Theofanidis’ Heart of a Soldier and Peter in Mark Adamo’s The Gospel of Mary Magdalene. An alumnus of the San Francisco Opera’s Merola Opera Program, Burden is a member of the voice faculty at The Juilliard School and the Mannes School of Music. Appearing in prestigious opera houses in the United States and Europe, his repertoire also includes the title roles of Les Contes d'Hoffmann, Faust, Pelléas et Mélisande, Roméo et Juliette, Béatrice and Bénédict, Candide, and Acis and Galatea; Loge in Das Rheingold, Aschenbach in Death in Venice, Florestan in Fidelio, Don José in Carmen, Pylade in Iphigénie en Tauride, Edgardo in Lucia di Lammermoor, Ferrando in Così fan tutte and Lensky in Eugene Onegin. A supporter of new works, he appeared in the U.S. premiere of Henze’s Phaedra at Opera Philadelphia and created the roles of George Bailey at Houston Grand Opera, Frank Harris in Theodore Morrison's Oscar at the Santa Fe Opera, Gilbert Griffiths in Tobias Picker’s An American Tragedy at the Metropolitan Opera, Dodge in Daron Hagen’s Amelia at Seattle Opera, Ruben Iglesias in Jimmy López's Bel Canto at Lyric Opera of Chicago, and Nikolaus Sprink in Kevin Puts’ Pulitzer Prize-winning Silent Night at Minnesota Opera. -

HELEN PREJEAN People of God Remarkable Lives, Heroes of Faith

HELEN PREJEAN People of God Remarkable Lives, Heroes of Faith People of God is a series of inspiring biographies for the general reader. Each volume offers a compelling and honest narrative of the life of an important twentieth- or twenty- first-century Catholic. Some living and some now deceased, each of these women and men has known challenges and weaknesses familiar to most of us but responded to them in ways that call us to our own forms of heroism. Each of- fers a credible and concrete witness of faith, hope, and love to people of our own day. John XXIII Massimo Faggioli Oscar Romero Kevin Clarke Thomas Merton Michael W. Higgins Francis Michael Collins Flannery O’Connor Angela O’Donnell Martin Sheen Rose Pacatte Jean Vanier Michael W. Higgins Dorothy Day Patrick Jordan Luis Antonio Tagle Cindy Wooden Georges and Pauline Vanier Mary Francis Coady Joseph Bernardin Steven P. Millies Corita Kent Rose Pacatte Daniel Rudd Gary B. Agee Helen Prejean Joyce Duriga Paul VI Michael Collins Elizabeth Johnson Heidi Schlumpf Thea Bowman Maurice J. Nutt Shahbaz Bhatti John L. Allen Jr. More titles to follow. Helen Prejean Death Row’s Nun Joyce Duriga LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Cover design by Red+Company. Cover illustration by Philip Bannister. © 2017 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. -

Dead Man Walking-An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States

NYLS Journal of Human Rights Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 8 Fall 1994 DEAD MAN WALKING-AN EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES Ronald J. Tabak Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_human_rights Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Tabak, Ronald J. (1994) "DEAD MAN WALKING-AN EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES," NYLS Journal of Human Rights: Vol. 12 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_human_rights/vol12/iss1/8 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of Human Rights by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. DEAD MAN WALKING-AN EYEWrTNESS ACCOUNT OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES. By Sister Helen Prejean, C.S.J. New York Random House (1993). Pp. 278. $21.00. Reviewed by Ronald J. Tabak" December of 1994, when I wrote this review of Sister Helen Prejean's fascinating and sobering book, Dead Man Walking-An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States,1 was ten years to the month of the execution of my client, Robert Lee Willie. It was also, not coincidentally, ten years to the month in which I first encountered Sister Helen. I had represented Willie in seeking certiorari from the United States Supreme Court in late 1983 to review his conviction and sentence, which was all I had originally agreed to do on his behalf. But when I learned that if I did not continue to represent him, there would likely be no one to represent him in his first state post-conviction and federal habeas corpus proceedings, I felt I could not walk away. -

Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking, 44 Val

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 44 Number 1 Fall 2009 pp.37-68 Fall 2009 Reflections on the Needle: oe,P Baze, Dead Man Walking Robert Batey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert Batey, Reflections on the Needle: Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking, 44 Val. U. L. Rev. 37 (2009). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol44/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Batey: Reflections on the Needle: Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking REFLECTIONS ON THE NEEDLE: POE, BAZE, DEAD MAN WALKING Robert Batey* The goal of most of the “Law and . .” movements is to bring the perspective of the humanities to legal issues. Literature and film, for examples, can cause one to envision such issues afresh. Sometimes this viewing from a new angle is premeditated, but sometimes it sneaks up on you. During a recent fall semester my colleague, Kristen Adams, asked that I speak to Stetson’s Honors Colloquium1 on a law and literature topic.2 The only date we could work out was Halloween, and so Professor Adams and I laughingly agreed that Edgar Allan Poe would be an appropriate choice. Dipping into Poe’s stories (all of which seem to be online), I immediately sensed their resonance with the law of capital punishment, another of my academic interests.3 The Fall of the House of Usher seemed filled with images of the death house.