The Death Penalty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications Summer 1996 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Roberta M. Harding University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Repository Citation Harding, Roberta M., "Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment" (1996). Law Faculty Scholarly Articles. 563. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Notes/Citation Information Robert M. Harding, Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment, 30 U.S.F. L. Rev. 1167 (1996). This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment By ROBERTA M. HARDING* FILMMAKING HAS EXISTED since the late 1890s. 1 Capital punish- ment has existed even longer.2 With more than 3,000 individuals lan- guishing on the nation's death rows3 and more than 300 executions occurring since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976,4 capital pun- ishment has become one of modem society's most controversial issues. The cinematic world has not been immune from this debate. -

The Just Mercy Summer Grace Group

Welcome to the Just Mercy Summer Grace Group Linda Hitchens and Ed Bryant Bless You ▪ Awesome response to the class ▪ We will make every effort to make this a rewarding experience ▪ You make the class ▪ Thank you, Grace ▪ Opening Prayer Course Structure and Plan ▪ Lessons based upon the book but will reference the movie ▪ Lessons ▪ Introduction – Chapter 3 June 3 ▪ Chapter 4 – Chapter 6 June 17 ▪ Chapter 7 – Chapter 10 July 1 ▪ Chapter 11 – Chapter 13 July 15 ▪ Chapter 14 – Epilogue July 29 ▪ Final session – TBD August 12 ▪ As always, we will be flexible and adjust as the Spirit guides us Introduction, Higher Ground ▪ Despite not having any background in law, Bryan Stevenson decided to obtain a law degree as means to solving racial injustice in America ▪ Wow, just let that sink in; he is in his early 20s ▪ Felt disconnected while studying at Harvard ▪ As an intern, asked to visit a Georgian death row prisoner. ▪ No lawyer available ▪ He is sent to tell Henry, the prisoner, “You will not be killed in the next year” ▪ Three-hour conversation ▪ Henry alters Bryan’s understanding of human potential, redemption, and hopefulness ▪ The question of how and why people are judged unfairly The History of Mass Incarceration and Extreme Punishment ▪ Historical overview ▪ Read together summary on bottom of 14 to end of page 15 ▪ Collateral consequences of mass incarceration ▪ Homelessness, unemployment, loss of right to vote, mental illness ▪ Economic costs ▪ Creation of new crimes, harsher and longer sentences ▪ “The opposite of poverty is not wealth; the opposite of poverty is justice.” ▪ Group Discussion ▪ Thoughts? Reactions? U.S. -

Social Justice Booklist

Social Justice Booklist An African American and Latinx History of the US by Paul Ortiz "...a bottom-up history told from the viewpoint of African American and Latinx activists and revealing the radically different ways people of the diaspora addressed issues still plaguing the United States today"- Amazon.com Becoming by Michelle Obama An intimate, powerful, and inspiring memoir Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates Author Ta-Nehisi Coates offers a powerful framework for understanding our nation's current crisis on race, illuminating the past and confronting the present as a way to present a vision forward. Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice that Shapes what we See, Think, and Do by Jennifer Eberhardt Explores the daily repercussions of implicit bias, discussing its impact on education, employment, housing, and criminal justice. Born a Crime: stories from a South African childhood by Trevor Noah "Trevor Noah's unlikely path from apartheid South Africa to the desk of The Daily Show began with a criminal act: his birth" --Amazon.com The Bridge by Bill Konigsberg "Aaron and Tillie do not know each other, but they both feel suicidal and arrive at the George Washington birdge at the same time, intending to jump. Includes resources about suicide prevention and suicide prevention for LGBTQIA+ youth." --Provided by publisher Call Me American: A Memoir by Abdi Nor Iftin The true story of a boy living in war-torn Somalia who escapes to America Courageous Conversations About Race: A Field Guide for Achieving Equality in Schools by Glenn E. Singleton Examines the achievement gap between students of different races and explains the need for candid, courageous conversations about race to help educators understand performance inequality and develop a curriculum that promotes true academic parity. -

Straight Is the Gate: Capital Clemency in the United States from Gregg to Atkins

Volume 33 Issue 2 Beyond Atkins: A Symposium on the Implications of Atkins v. Virginia (Summer 2003) Spring 2003 Straight Is the Gate: Capital Clemency in the United States from Gregg to Atkins Elizabeth Rapaport University of New Mexico - Main Campus Recommended Citation Elizabeth Rapaport, Straight Is the Gate: Capital Clemency in the United States from Gregg to Atkins, 33 N.M. L. Rev. 349 (2003). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmlr/vol33/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The University of New Mexico School of Law. For more information, please visit the New Mexico Law Review website: www.lawschool.unm.edu/nmlr STRAIGHT IS THE GATE: CAPITAL CLEMENCY IN THE UNITED STATES FROM GREGG TO ATKINS ELIZABETH RAPAPORT* straight is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it. Matthew 7:14 (King James) This Article will examine executive clemency decisions in capital cases, from 1977, the year of the first execution after the Supreme Court sanctioned the resumption of executions in Gregg v. Georgia,' until June of 2002, when Atkins v. Virginia2 was decided.3 The power of the executive to grant clemency to a capital defendant can be viewed as a gateway--one last chance to be spared capital punishment. The gateway to clemency has been exceedingly narrow in this quarter century era of capital punishment. Perhaps surprisingly, it has been very narrow indeed for the three classes of capital prisoners who are the focus of this Beyond Atkins Symposium,4 and who might be expected to be particularly suitable candidates for clemency, i.e., juveniles,5 the mentally retarded, and the mentally ill. -

Transforming Times As Sisters of St

Spring/Summer y Vol. 3 y no. 1 ONEThe CongregaTion of The SiSTerS of ST. JoSeph imagine Transforming Times as Sisters of St. Joseph flows from the purpose for which the congregation exists: We live and work that all people may be united with god and with one another. We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, living out of our common Spring/Summer 2011 y Vol. 3 y no. 1 tradition, witness to God’s love transforming us and our world. Recognizing that we are called to incarnate our mission and imagineONE is published twice yearly, charism in our world in fidelity to God’s call in the Gospel, we in Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter, commit ourselves to these Generous Promises through 2013. by the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph. z We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, promise to take the risk CENTRAL OFFICE to surrender our lives and resources to work for specific 3430 Rocky River Drive systemic change in collaboration with others so that the Cleveland, OH 44111-2997 Ourhungers mission of the world might be fed. (216) 252-0440 WITH SIGNIFICANT PRESENCE IN z We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, promise to recognize the reality that Earth is dying, to claim our oneness with Baton Rouge, LA Earth and to take steps now to strengthen, heal and renew Cincinnati, OH Crookston, MN the face of Earth. Detroit, MI z Kyoto, Japan We, the Congregation of St. Joseph, promise to network LaGrange Park, IL with others across the world to bring about a shift in the Minneapolis-St. -

FURMAN V. GEORGIA a Report by the SOUTHERN CENTER for HUMAN RIGHTS

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT on the 25th Anniversary of FURMAN v. GEORGIA A report by the SOUTHERN CENTER for HUMAN RIGHTS STEPHEN B. BRIGHT, DIRECTOR June 26, 1997 CAPITAL PUNISHMENT on the 25th ANNIVERSARY of FURMAN v. GEORGIA A report by the SOUTHERN CENTER for HUMAN RIGHTS These death sentences are cruel and unusual in the same way that being struck by lightning is cruel and unusual.... [T]he petitioners are among a capriciously selected random handful upon whom the sentence of death has in fact been imposed. - Justice Potter Stewart, Furman v. Georgia, June 29, 1972 Today, administration of the death penalty, far from being fair and consistent, is instead a haphazard maze of unfair prac- tices with no internal consistency. - American Bar Association's Report Regarding its Call for A Moratorium on Executions, February 1997 •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 RACE 5 POVERTY 11 ARBITRARINESS 21 INNOCENCE 24 MENTAL RETARDATION 27 MENTAL ILLNESS 30 CHILDREN 33 INTRODUCTION From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death. For more than 20 years, I have endeavored— indeed, I have struggled—along with a majority of this Court, to develop procedural and substantive rules that would lend more than the mere appearance of fairness to the death penalty endeavor. Rather than continue to coddle the Court's delusion that the desired level of fairness has been achieved and the need for regulation eviscerated, I feel morally and intellectually obligated simply to concede that the death penalty experiment has failed. - Justice Harry Blackmun, Callins v. Collins 114 S. Ct. 1127, 1130 (1994) (dissenting from denial of certiorari) Twenty-five years ago on June 29, 1972, the United States Supreme Court held in Furman v. -

Marco Movies

Movies starting Friday, January 24 www.FMBTheater.com America’s Original First Run Food Theater! We recommend that you arrive 30 minutes before ShowTime. “Just Mercy” Rated PG-13 Run Time 2:15 Starring Michael B. Jordan, Jamie Foxx and Brie Larson Start 2:30 5:30 8:20 End 4:45 7:45 10:35 Rated PG-13 for thematic content including some racial epithets. “1917” Rated R Run Time 2:00 Starring George MacKay, Colin Firth and Benedict Cumberbatch Start 2:45 5:40 8:30 End 4:45 7:40 10:30 Rated R for violence, some disturbing images, and language. “Little Women” Rated PG-13 Run Time 2:15 Starring Saoirse Ronan, Emma Watson and Meryl Streep Start 2:25 5:30 8:20 End 4:40 7:45 10:35 Rated PG for thematic elements and brief smoking. “Dolittle” Rated PG Run Time 1:45 Starring Robert Downey Jr. Start 3:00 5:50 8:30 End 4:45 7:35 10:15 Rated PG for some action, rude humor and brief language. *** Prices *** Matinees $11.00 (3D $13.00) Adults $13.50 (3D $15.50) Seniors and Children under 12 $11.00 (3D $13.00) Visit Beach Theater at www.fmbtheater.com facebook.com/BeachTheater 1917 (R) • George MacKay • Dean-Charles Chapman • Benedict Cumberbatch • At the height of the First World War, two young British soldiers, Schofield (George MacKay) and Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) are given a seemingly impossible mission. In a race against time, they must cross enemy territory and deliver a message that will stop a deadly attack on hundreds of soldiers--Blake's own brother among them. -

And Then One Night… the Making of DEAD MAN WALKING

And Then One Night… The Making of DEAD MAN WALKING Complete program transcript Prologue: Sister Helen and Joe Confession scene. SISTER HELEN I got an invitation to write to somebody on death row and then I walked with him to the electric chair on the night of April the fifth, 1984. And once your boat gets in those waters, then I became a witness. Louisiana TV footage of Sister Helen at Hope House NARRATION: “Dead Man Walking” follows the journey of a Louisiana nun, Sister Helen Prejean, to the heart of the death penalty controversy. We see Sister Helen visiting with prisoners at Angola. NARRATION: Her groundbreaking work with death row inmates inspired her to write a book she called “Dead Man Walking.” Her story inspired a powerful feature film… Clip of the film: Dead Man Walking NARRATION: …and now, an opera…. Clip from the opera “Dead Man Walking” SISTER HELEN I never dreamed I was going to get with death row inmates. I got involved with poor people and then learned there was a direct track from being poor in this country and going to prison and going to death row. NARRATION: As the opera began to take shape, the death penalty debate claimed center stage in the news. Gov. George Ryan, IL: I now favor a moratorium because I have grave concerns about our state’s shameful record of convicting innocent people and putting them on death row. Gov. George W. Bush, TX: I’ve been asked this question a lot ever since Governor Ryan declared a moratorium in Illinois. -

The Journey of Dead Man Walking

Sacred Heart University Review Volume 20 Issue 1 Sacred Heart University Review, Volume XX, Article 1 Numbers 1 & 2, Fall 1999/ Spring 2000 2000 The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Helen Prejean Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview Recommended Citation Prejean, Helen (2000) "The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking," Sacred Heart University Review: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the SHU Press Publications at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sacred Heart University Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Cover Page Footnote This is a lightly edited transcription of the talk delivered by Sister Prejean at Sacred Heart University on October 31, 2000, sponsored by the Hersher Institute for Applied Ethics and by Campus Ministry. This article is available in Sacred Heart University Review: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 Prejean: The Journey of Dead Man Walking SISTER HELEN PREJEAN, C.S.J. The Journey of Dead Man Walking I'm glad to be with you. I'm going to bring you with me on a journey, an incredible journey, really. I never thought I was going to get involved in these things, never thought I would accompany people on death row and witness the execution of five human beings, never thought I would be meeting with murder victims' families and accompanying them down the terrible trail of tears and grief and seeking of healing and wholeness, never thought I would encounter politicians, never thought I would be getting on airplanes and coming now for close to fourteen years to talk to people about the death penalty. -

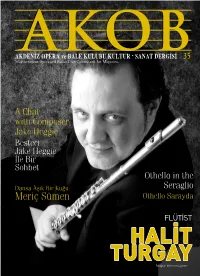

An Interview with Jake Heggie

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean. -

Execution Ritual : Media Representations of Execution and the Social Construction of Public Opinion Regarding the Death Penalty

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2011 Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty. Emilie Dyer 1987- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Dyer, Emilie 1987-, "Execution ritual : media representations of execution and the social construction of public opinion regarding the death penalty." (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 388. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/388 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXECUTION RITUAL: MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fullfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May, 2011 -------------------------------------------------------------- EXECUTION RITUAL : MEDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF EXECUTION AND THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF PUBLIC OPINION REGARDING THE DEATH PENALTY By Emilie Brook Dyer B.A., University of Louisville, 2009 A Thesis Approved on April 11, 2011 by the following Thesis Committee: Thesis Director (Dr. -

![Death Penalty As the Answer to Crime: Costly, Counterproductive and Corrupting [Advocate in Residence] Stephen B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4674/death-penalty-as-the-answer-to-crime-costly-counterproductive-and-corrupting-advocate-in-residence-stephen-b-1074674.webp)

Death Penalty As the Answer to Crime: Costly, Counterproductive and Corrupting [Advocate in Residence] Stephen B

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Santa Clara University School of Law Santa Clara Law Review Volume 36 | Number 4 Article 5 1-1-1996 Death Penalty as the Answer to Crime: Costly, Counterproductive and Corrupting [Advocate in Residence] Stephen B. Bright Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Stephen B. Bright, Death Penalty as the Answer to Crime: Costly, Counterproductive and Corrupting [Advocate in Residence], 36 Santa Clara L. Rev. 1069 (1996). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol36/iss4/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ADVOCATE IN RESIDENCE THE DEATH PENALTY AS THE ANSWER TO CRIME: COSTLY, COUNTERPRODUCTIVE AND CORRUPTING Stephen B. Bright* I appreciate the opportunity to make some remarks about capital punishment and about the crime debate in our country today. Unfortunately, what is called a crime debate is really no debate at all, but an unseemly competition among politicians to show how tough they are on crime by support- ing harsher penalties and less due process. The death pen- alty and long prison sentences are being put forward as an answer to the problem of violent crime. This approach is ex- pensive and counterproductive. It is corrupting the courts and diverting our efforts from the important problems of ra- cial prejudice, poverty, violence and crime.