Teaching Kit Dead Man Walking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Law Faculty Scholarly Articles Law Faculty Publications Summer 1996 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Roberta M. Harding University of Kentucky College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Repository Citation Harding, Roberta M., "Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment" (1996). Law Faculty Scholarly Articles. 563. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Publications at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment Notes/Citation Information Robert M. Harding, Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment, 30 U.S.F. L. Rev. 1167 (1996). This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/law_facpub/563 Celluloid Death: Cinematic Depictions of Capital Punishment By ROBERTA M. HARDING* FILMMAKING HAS EXISTED since the late 1890s. 1 Capital punish- ment has existed even longer.2 With more than 3,000 individuals lan- guishing on the nation's death rows3 and more than 300 executions occurring since the reinstatement of the death penalty in 1976,4 capital pun- ishment has become one of modem society's most controversial issues. The cinematic world has not been immune from this debate. -

“Dead Man Walking” by Sister Helen Prejean

“Dead man walking” by Sister Helen Prejean At first I would like to say a few words about the authors biography and after that I will come to the story of the book which is completely different from the story of the film and in the end we will see a little excerpt of the German version of the film Sister Helen Prejean Sister Helen Prejean, the Author of dead man walking, was born on the 21st of April in 1939, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and has lived and worked in Louisiana all her life. She joined the Sisters of St. Joseph in 1957. Her ministries have included teaching junior and senior high students. Involvement with poor inner city residents in the St. Thomas Housing Project in New Orleans in 1981 led her to prison ministry where she counseled death row inmates in the Louisiana State Penitentiary. She has accompanied three men to the electric chair and witnessed their deaths. Since then, she has devoted her energies to the education of the public about the death penalty by lecturing, organizing and writing. She also has befriended murder victims' families and she helped to found "Survive" a victims advocacy group in New Orleans. Currently, she continues her ministry to death row inmates and murder victims'. She also is a member of Amnesty International. The story In 1977, Patrick and his Brother Eddie had abducted a teenage couple, Loretta Bourque and David Le Blanc, from a lovers’ lane, raped the girl, forced them to lie face down and shot them into the head. -

And Then One Night… the Making of DEAD MAN WALKING

And Then One Night… The Making of DEAD MAN WALKING Complete program transcript Prologue: Sister Helen and Joe Confession scene. SISTER HELEN I got an invitation to write to somebody on death row and then I walked with him to the electric chair on the night of April the fifth, 1984. And once your boat gets in those waters, then I became a witness. Louisiana TV footage of Sister Helen at Hope House NARRATION: “Dead Man Walking” follows the journey of a Louisiana nun, Sister Helen Prejean, to the heart of the death penalty controversy. We see Sister Helen visiting with prisoners at Angola. NARRATION: Her groundbreaking work with death row inmates inspired her to write a book she called “Dead Man Walking.” Her story inspired a powerful feature film… Clip of the film: Dead Man Walking NARRATION: …and now, an opera…. Clip from the opera “Dead Man Walking” SISTER HELEN I never dreamed I was going to get with death row inmates. I got involved with poor people and then learned there was a direct track from being poor in this country and going to prison and going to death row. NARRATION: As the opera began to take shape, the death penalty debate claimed center stage in the news. Gov. George Ryan, IL: I now favor a moratorium because I have grave concerns about our state’s shameful record of convicting innocent people and putting them on death row. Gov. George W. Bush, TX: I’ve been asked this question a lot ever since Governor Ryan declared a moratorium in Illinois. -

The Journey of Dead Man Walking

Sacred Heart University Review Volume 20 Issue 1 Sacred Heart University Review, Volume XX, Article 1 Numbers 1 & 2, Fall 1999/ Spring 2000 2000 The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Helen Prejean Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview Recommended Citation Prejean, Helen (2000) "The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking," Sacred Heart University Review: Vol. 20 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the SHU Press Publications at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sacred Heart University Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The ourJ ney of Dead Man Walking Cover Page Footnote This is a lightly edited transcription of the talk delivered by Sister Prejean at Sacred Heart University on October 31, 2000, sponsored by the Hersher Institute for Applied Ethics and by Campus Ministry. This article is available in Sacred Heart University Review: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/shureview/vol20/iss1/1 Prejean: The Journey of Dead Man Walking SISTER HELEN PREJEAN, C.S.J. The Journey of Dead Man Walking I'm glad to be with you. I'm going to bring you with me on a journey, an incredible journey, really. I never thought I was going to get involved in these things, never thought I would accompany people on death row and witness the execution of five human beings, never thought I would be meeting with murder victims' families and accompanying them down the terrible trail of tears and grief and seeking of healing and wholeness, never thought I would encounter politicians, never thought I would be getting on airplanes and coming now for close to fourteen years to talk to people about the death penalty. -

An Interview with Jake Heggie

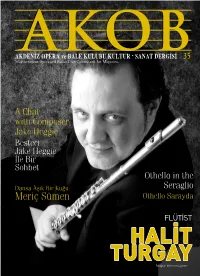

35 Mediterranean Opera and Ballet Club Culture and Art Magazine A Chat with Composer Jake Heggie Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Othello in the Dansa Âşık Bir Kuğu: Seraglio Meriç Sümen Othello Sarayda FLÜTİST HALİT TURGAY Fotoğraf: Mehmet Çağlarer A Chat with Jake Heggie Composer Jake Heggie (Photo by Art & Clarity). (Photo by Heggie Composer Jake Besteci Jake Heggie İle Bir Sohbet Ömer Eğecioğlu Santa Barbara, CA, ABD [email protected] 6 AKOB | NİSAN 2016 San Francisco-based American composer Jake Heggie is the author of upwards of 250 Genç Amerikalı besteci Jake Heggie şimdiye art songs. Some of his work in this genre were recorded by most notable artists of kadar 250’den fazla şarkıya imzasını atmış our time: Renée Fleming, Frederica von Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia bir müzisyen. Üstelik bu şarkılar günümüzün McNair and others. He has also written choral, orchestral and chamber works. But en ünlü ses sanatçıları tarafından yorumlanıp most importantly, Heggie is an opera composer. He is one of the most notable of the kaydedilmiş: Renée Fleming, Frederica von younger generation of American opera composers alongside perhaps Tobias Picker Stade, Carol Vaness, Joyce DiDonato, Sylvia and Ricky Ian Gordon. In fact, Heggie is considered by many to be simply the most McNair bu sanatçıların arasında yer alıyor. Heggie’nin diğer eserleri arasında koro ve successful living American composer. orkestra için çalışmalar ve ayrıca oda müziği parçaları var. Ama kendisi en başta bir opera Heggie’s recognition as an opera composer came in 2000 with Dead Man Walking, bestecisi olarak tanınıyor. Jake Heggie’nin with libretto by Terrence McNally, based on the popular book by Sister Helen Préjean. -

Dead Man Walking-An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States

NYLS Journal of Human Rights Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 8 Fall 1994 DEAD MAN WALKING-AN EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES Ronald J. Tabak Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_human_rights Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Tabak, Ronald J. (1994) "DEAD MAN WALKING-AN EYEWITNESS ACCOUNT OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES," NYLS Journal of Human Rights: Vol. 12 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_human_rights/vol12/iss1/8 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of Human Rights by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. DEAD MAN WALKING-AN EYEWrTNESS ACCOUNT OF THE DEATH PENALTY IN THE UNITED STATES. By Sister Helen Prejean, C.S.J. New York Random House (1993). Pp. 278. $21.00. Reviewed by Ronald J. Tabak" December of 1994, when I wrote this review of Sister Helen Prejean's fascinating and sobering book, Dead Man Walking-An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States,1 was ten years to the month of the execution of my client, Robert Lee Willie. It was also, not coincidentally, ten years to the month in which I first encountered Sister Helen. I had represented Willie in seeking certiorari from the United States Supreme Court in late 1983 to review his conviction and sentence, which was all I had originally agreed to do on his behalf. But when I learned that if I did not continue to represent him, there would likely be no one to represent him in his first state post-conviction and federal habeas corpus proceedings, I felt I could not walk away. -

Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking, 44 Val

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 44 Number 1 Fall 2009 pp.37-68 Fall 2009 Reflections on the Needle: oe,P Baze, Dead Man Walking Robert Batey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert Batey, Reflections on the Needle: Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking, 44 Val. U. L. Rev. 37 (2009). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol44/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Batey: Reflections on the Needle: Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking REFLECTIONS ON THE NEEDLE: POE, BAZE, DEAD MAN WALKING Robert Batey* The goal of most of the “Law and . .” movements is to bring the perspective of the humanities to legal issues. Literature and film, for examples, can cause one to envision such issues afresh. Sometimes this viewing from a new angle is premeditated, but sometimes it sneaks up on you. During a recent fall semester my colleague, Kristen Adams, asked that I speak to Stetson’s Honors Colloquium1 on a law and literature topic.2 The only date we could work out was Halloween, and so Professor Adams and I laughingly agreed that Edgar Allan Poe would be an appropriate choice. Dipping into Poe’s stories (all of which seem to be online), I immediately sensed their resonance with the law of capital punishment, another of my academic interests.3 The Fall of the House of Usher seemed filled with images of the death house. -

Oral History Center University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Frederica Von Stade Frederica Von Stade

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Frederica von Stade Frederica von Stade: American Star Mezzo-Soprano Interviews conducted by Caroline Crawford in 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015 Copyright © 2020 by The Regents of the University of California Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Frederica von Stade dated February 2, 2012. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Dead Man Walking Tells the Story of Sister Helen Prejean, Who Establishes a Special Relationship with Matthew Poncelet, a Prisoner on Death Row

Dead Man Walking tells the story of Sister Helen Prejean, who establishes a special relationship with Matthew Poncelet, a prisoner on death row. Matthew Poncelet has been in prison six years, awaiting his execution by lethal injection for killing a teenage couple. He committed the crime in company with Carl Vitello, who received life imprisonment as a result of being able to afford a better lawyer. The film consolidates two different people (Elmo Patrick Sonnier and Robert Lee Willie) whom Prejean counseled on death row into one character, as well as merging Prejean in Cambridge, Mass. in Sept. 2000 their crimes and their victims' families into one event. In 1981, she started working with convicted murderer Elmo Patrick Sonnier, who was sentenced to death by electrocution. Sonnier had received a sentence of death in April 1978 for the November 5, 1977 rape and murder of Loretta Ann Bourque, 18, and the murder of David LeBlanc, 17. He was executed in 1984. The account is based on the inmate Robert Lee Willie who, with his friend Joseph Jesse Vaccaro, raped and killed 18- year-old Faith Hathaway in May 1980, eight days later kidnapping a couple from a wooded lovers' lane, raping the 16-year-old girl, Debbie Morris, and then stabbing and shooting her boyfriend, 20-year-old Mark Brewster, leaving him tied to a tree paralyzed from the waist down. Willie was executed in 1984. She has been the spiritual adviser to several convicted murderers in Louisiana, and accompanied them to their electrocutions. St. Anthony Messenger says “you could call her the Mother Teresa of Death Row.” After watching Elmo Patrick Sonnier executed in 1984, she said, “I couldn't watch someone being killed and walk away. -

FINDING AID for Sr. Helen Prejean Papers

DePaul University Special Collections and Archives: Sr. Helen Prejean Papers FINDING AID FOR Sr. Helen Prejean Papers DePaul University Special Collections and Archives Department 2350 N Kenmore Ave., Chicago, IL 60614 [email protected] 773-325-7864 Page 1 of 84 DePaul University Special Collections and Archives: Sr. Helen Prejean Papers Collection Description Sr. Helen Prejean Papers Date Range: 1967-2011 Bulk Dates: 1985-2010 Quantity: 65.75 linear feet (144 boxes) Creator Prejean, Sr. Helen History Sr. Helen Prejean was born on April 21, 1939, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. She joined the Sisters of St. Joseph of Medaille in 1957 (now known as the Congregation of St. Joseph) and received a B.A. in English and Education from St. Mary's Dominican College, New Orleans in 1962. In 1973, she earned an M.A. in Religious Education from St. Paul's University in Ottawa, Canada. She has been the Religious Education Director at St. Frances Cabrini Parish in New Orleans, the Formation Director for her religious community, and has taught junior and senior high school students. Sr. Helen began her prison ministry in 1981 when she dedicated her life to the poor of New Orleans. While living in the St. Thomas housing project, she became pen pals with Patrick Sonnier, the convicted killer of two teenagers, sentenced to die in the electric chair of Louisiana's Angola State Prison. She started to visit Sonnier, as well as maintaining regular correspondence. When Sonnier was executed in 1984, Sr. Helen witnessed his execution as his spiritual advisor, and has been campaigning against the death penalty ever since. -

Reflections on the Needle: Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking, 44 Val

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ValpoScholar Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 44 Number 1 Fall 2009 pp.37-68 Fall 2009 Reflections on the Needle: oe,P Baze, Dead Man Walking Robert Batey Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert Batey, Reflections on the Needle: Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking, 44 Val. U. L. Rev. 37 (2009). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol44/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Batey: Reflections on the Needle: Poe, Baze, Dead Man Walking REFLECTIONS ON THE NEEDLE: POE, BAZE, DEAD MAN WALKING Robert Batey* The goal of most of the “Law and . .” movements is to bring the perspective of the humanities to legal issues. Literature and film, for examples, can cause one to envision such issues afresh. Sometimes this viewing from a new angle is premeditated, but sometimes it sneaks up on you. During a recent fall semester my colleague, Kristen Adams, asked that I speak to Stetson’s Honors Colloquium1 on a law and literature topic.2 The only date we could work out was Halloween, and so Professor Adams and I laughingly agreed that Edgar Allan Poe would be an appropriate choice. -

BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION Sister Helen Prejean Is Known

BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION Sister Helen Prejean is known around the world for her tireless work against the death penalty. She has been instrumental in sparking national dialogue on capital punishment and in shaping the Catholic Church’s newly vigorous opposition to all executions. In 1982, Sister Helen started corresponding with Patrick Sonnier, sentenced to die in the electric chair of Louisiana’s Angola State Prison for the murder of two teenagers. Sonnier asked her to become his spiritual advisor and she accepted. In 1984, Elmo Patrick Sonnier was put to death in the electric chair. Sister Helen was there to witness his execution. In the following months, she became spiritual advisor to another death row inmate, Robert Lee Willie, who soon met the same fate as Sonnier. After witnessing this second execution, Sister Helen realized that this lethal act, performed at midnight, would remain hidden unless she spoke up about it. She came together with others to hold execution vigils and to march to draw attention to the issue. She founded a support group for victims’ family members, called Survive. And she sat down and wrote a book, Dead Man Walking: An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States. Dead Man Walking ignited a national debate on capital punishment and it inspired an Academy Award winning movie, a play and an opera. Sister Helen’s second book, The Death of Innocents, An Eyewitness Account of Wrongful Executions, was published in 2004 and her memoir, River of Fire, in 2019. With capital punishment still practiced in 29 states, Sister Helen divides her time between campaigning against the death penalty, counseling individual death row prisoners, and working with murder victims’ family members.