1955 Lancia Aurelia Spider B24S-1117

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road & Track Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j38wwz No online items Guide to the Road & Track Magazine Records M1919 David Krah, Beaudry Allen, Kendra Tsai, Gurudarshan Khalsa Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2015 ; revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Road & Track M1919 1 Magazine Records M1919 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Road & Track Magazine records creator: Road & Track magazine Identifier/Call Number: M1919 Physical Description: 485 Linear Feet(1162 containers) Date (inclusive): circa 1920-2012 Language of Material: The materials are primarily in English with small amounts of material in German, French and Italian and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The records of Road & Track magazine consist primarily of subject files, arranged by make and model of vehicle, as well as material on performance and comparison testing and racing. Conditions Governing Use While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching, and private study. Any transmission or reproduction beyond that allowed by fair use requires permission from the owners of rights, heir(s) or assigns. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Road & Track Magazine records (M1919). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. Note that material must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. -

Aurelia B20 Ii Serie 1952

Lancia AURELIA B20 II SERIE 1952 HISTORY TECHNICAL DATA GALLERY he Aurelia B20 is unanimously recognized by experts as Pininfarina’s true masterpiece, which was entrusted with the final contract for the mass production of this model. TIn March 1952, on the occasion of the Geneva Motor Show, the B20 2nd series was presented. The car has a modified distribution with a slightly increased compression ratio, unchanged driving torque, but a higher power (80 HP instead of 75) that pushes the car up to 162 kph. The second series stands outwardly for the adoption of new chrome bumpers, for the back of the body where the so-called “tails” (codine in italian) appear and for the addition of a chrome profile under the doors, modifications that contribute to increase the lateral slimness of the car. Inside, the new dashboard features two circular instruments, with a new tachometer. Produced in 731 units from March 1952 to February 1953 in the B20 versions, coupé 2 doors, 2-3 seats and with right-hand drive. ur Lancia Aurelia B20 II Serie Car eligible for the MilleMiglia. It is a unique B20, in good condition and customized according to the requests of its Ofirst owner. This model is considered an “extra series” due to the modification of the floor gearbox, the three-spoke Nardi steering wheel and the original Lancia “Amaranto La Plata” livery. Refined interiors with seats restored to new in double cream and brown coloring. very mechanical component of the car has recently been overhauled, so today this car represents an important opportunity for any collector of the Lancia brand looking for Ea “post war” car with good performance. -

LANCIA Storie Di Innovazione Tecnologica Nelle Automobili Storie Di Innovazione Tecnologica Nelle Automobili

LORENZO MORELLO LANCIA Storie di innovazione tecnologica nelle automobili Storie di innovazione tecnologica nelle automobili LORENZO Morello LANCIA Storie di innovazione tecnologica nelle automobili Editing, progettazione grafica e impaginazione: Fregi e Majuscole, Torino © 2014 Lorenzo Morello Stampato nell’anno 2014 a cura di Fiat Group Marketing & Corporate Communication S.p.A. Logo di prima copertina: courtesy di Fiat Group Marketing & Corporate Communication S.p.A. PRESENTAZIONE volontari del progetto STAF (Storia della Tecnologia delle Automobili FIAT), istituito nel 2009 al fine di selezionare i disegni tecnici più rilevanti per documentare l’e- I voluzione tecnica delle automobili FIAT, sono venuti a contatto anche con i disegni Lancia, contenuti in una sezione dedicata dell’Archivio Storico FIAT: il materiale vi era stato trasferito quando, nel 1984, la Direzione tecnica di FIAT Auto, il settore aziendale incaricato di progettare le automobili dei marchi FIAT, Lancia e Autobianchi, era stata riunita in un unico fabbricato, all’interno del comprensorio di Mirafiori. Fu nell’oc- casione del ritrovamento di questo nucleo di disegni che i partecipanti al progetto si proposero di applicare il metodo impiegato nel predisporre il materiale raccolto nel libro FIAT, storie di innovazione tecnologica nelle automobili, anche per preparare un libro analogo dedicato alle automobili Lancia. Questo secondo libro, attraverso l’esame dei disegni tecnici, del materiale d’archivio e delle fotografie di automobili sopravvissute, illustra l’evoluzione delle vetture Lancia e i loro contenuti innovativi, spesso caratterizzati da elementi di assoluta originalità. Il reperimento del materiale si è mostrato, tuttavia, più arduo rispetto al lavoro sulle vetture FIAT, almeno per le automobili più anziane, poiché l’archivio dei disegni Lancia era organizzato senza impiegare una struttura logica di supporto, per distinguere agevolmente i diversi gruppi funzionali dai particolari di puro dettaglio. -

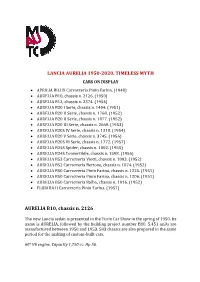

Lancia Aurelia 1950-2020. Timeless Myth Aurelia B10

LANCIA AURELIA 1950-2020. TIMELESS MYTH CARS ON DISPLAY • APRILIA BILUX Carrozzeria Pinin Farina. (1948) • AURELIA B10, chassis n. 2126. (1950) • AURELIA B12, chassis n. 2374. (1954) • AURELIA B20 I Serie, chassis n. 1404. (1951) • AURELIA B20 II Serie, chassis n. 1768. (1952) • AURELIA B20 II Serie, chassis n. 1877. (1952) • AURELIA B20 III Serie, chassis n. 2660. (1953) • AURELIA B20S IV Serie, chassis n. 1218. (1954) • AURELIA B20 V Serie, chassis n. 3745. (1956) • AURELIA B20S VI Serie, chassis n. 1772. (1957) • AURELIA B24S Spider, chassis n. 1002. (1955) • AURELIA B24S Convertibile, chassis n. 1598. (1956) • AURELIA B53 Carrozzeria Viotti, chassis n. 1003. (1952) • AURELIA B52 Carrozzeria Bertone, chassis n. 1074. (1952) • AURELIA B50 Carrozzeria Pinin Farina, chassis n. 1225. (1951) • AURELIA B50 Carrozzeria Pinin Farina, chassis n. 1206. (1951) • AURELIA B50 Carrozzeria Balbo, chassis n. 1016. (1952) • FLORIDA II Carrozzeria Pinin Farina. (1957) AURELIA B10, chassis n. 2126 The new Lancia sedan is presented in the Turin Car Show in the spring of 1950. Its name is AURELIA, followed by the building project number B10. 5.451 units are manufactured between 1950 and 1953. 583 chassis are also prepared in the same period for the making of custom-built cars. 60° V6 engine. Capacity 1,750 cc. Hp 56. AURELIA B12, chassis n. 2374 The new sedan, the AURELIA B12, is launched. It features a new body and new mechanical part with an increased capacity. The cylinder block casting, the crankshaft supports and the oil filter are new. The car on display, which has always been property of the Minerbi family, celebrated the Lancia 100th birthday in 2006 by going across the USA on the famous Route 66, driven by journalist Marcello Minerbi. -

May 2020 Alfa Bits

THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ALFA ROMEO OWNERS OF OREGON Volume 52, Issue 4 May 2020 Rebuilding the 1953 Lancia Aurelia B20GT Photo by Alex Carrara In this Issue About the Club The Board of Directors CONTENTS The Small Print 3 The Drivers Seat 4-5 2020 AROC National Convention Postponed 6 rd 2020 33 Northwest Classic Rally Postponed 7 James Parker photo Rebuilding the 1953 Lancia Aurelia B20GT 8 Activities Calendar 11 A Brief History of Car Time 12 AROO Members Anniversaries 15 AROO Cup Series Update 16 ADVERTISER INDEX Cup Rally Results 17 Vintage Underground 9 Meeting Minutes 18 Sports Car Market 10 It Was a Date 19 Cindy Banzer PDX Properties 14 Event Updates 23 Lonnie Dicus Windermere Realty Group 21 McGirr Tour Updates 24-25 Nasko’s Imports 21 Advertising information 30 Hagerty Insurance 22 Buy & Sell 32 Arrow Mechanical Company 22 NW Shelby Club Track Day 35 Columbia Roofing & Sheet Metal 26 The Back Seat 36 Cascade Investment Advisors 26 Guy’s Interior 30 30 CLICK HERE! PMX Custom Alternators & Starters To see videos of past AROO track events. Click on any advertiser to go directly to their ad. You can also click their ad to go directly to their website or contact info if available. 2 The Small Print FROM THE EDITOR Photo Cliff Brunk Still staying at home… ALFA BITS TV show to promote a sports car race Alfa Bits is the official newsletter of the Alfa which they dominated, winning converts in the Yep. Like all of you, I’m still at home. -

Lancia Aurelia 1950 – 2020 Timeless Myth

MAUTO – Museo Nazionale dell’Automobile di Torino LANCIA AURELIA 1950 – 2020 TIMELESS MYTH January 30, 2020 - May 3, 2020 MAUTO – Museo Nazionale dell’Automobile di Torino dedicates a retrospective exhibition to the fabulous Lancia Aurelia, one of the most advanced and refined cars of the Italian postwar production and a symbol of the extraordinary economic growth of Italy of those years. The exhibition will be open to the public from January 30 to May 3, 2020. Turin, January 30, 2020. MAUTO – Museo Nazionale dell’Automobile di Torino opens the exhibition LANCIA AURELIA 1950 – 2020. TIMELESS MYTH, an extraordinary exhibition divided into two sections that tells, through 18 exceptional standard and custom-built specimens, the evolution of this model, which was first presented in Turin in 1950. The Lancia Aurelia became popular all over the world as an expression of pure elegance, based on an ideal of polished simplicity, right from its first appearance, thanks to the successful creative and design partnership with Battista Pinin Farina. It was so successful as to be also featured in famous movies like "Il sorpasso” starring Vittorio Gassman and “Et Dieu créa la femme” starring Brigitte Bardot, which turned it into a worldwide icon of style. On the other hand, its technological contents, the result of technical collaborations with talented designers like Vittorio Jano and Francesco De Virgilio, imposed the Lancia brand as synonym with performance and sports cars and had legions of passionate collectors fall in love with the Aurelia. Just to name a few: the first 6V engine (which Ferrari engineers took inspiration from when designing the Dino 1500 cc); the aluminum die-cast engine block; the independent wheel rear suspension system; the rear position of the gear-change/engine to balance the car weight; the rear breaks in the same block as the engine in order to reduce the weight of suspended masses, which enhanced the grip. -

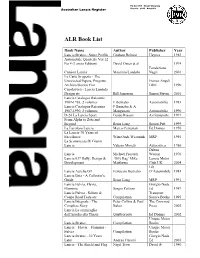

ALR Book List

PO Box 259 Mount Waverley Australian Lancia Register Victoria 3149 Australia ALR Book List Book Name Author Publisher Year Lancia Stratos - Super Profile Graham Robson Haynes 1983 Automobile Quarterly Vol 12 No 4 (Lancia Edition) David Owen et al 1974 Fondazione Camion Lancia Massimo Londolo Negri 2001 Le Carte Scoperte - The Uncovered Papers, Progetto Franco Angeli Archivo Storico Fiat Libri 1990 Capolavoro - Lancia Lambda Design etc Bill Jamieson Simon Stevin 2001 Lancia Catalogue Raisonne 1907-1983, 2 volumes F Bernabo Automobilia 1983 Lancia Catalogue Raisonne F Bernabo & A 1907-1990, 2 volumes Manganaro Automobilia 1990 D-24 La Lancia Sport Guido Rosani Avritemporte 1991 From Alpha to Zeta and Beyond Brian Long Sutton Pub 1999 La Favolosa Lancia Marco Centenari Ed Domus 1976 La Lancia-70 Years of Excellence Wim Oude Weernink MRP 1991 La Scommessa Di Gianni Lancia Valerio Moretti Autocritica 1986 Dalton Lancia Michael Frostick Watson 1976 Lancia 037 Rally, Design & 'Oily Rag' Mike Lancia Motor Development Matthews Club UK 2004 Lib Lancia Aurelia GT Ferruccio Bernabo D’Automobile 1983 Lancia Beta - A Collector's Guide Brian Long MRP 1991 Lancia Fulvia, Flavia, Giorgio Nada Flaminia Sergio Puttioni Ed 1989 Lancia Fulvia - Saloon & Transport Coupe Road Tests etc Compilation Source Books 1995 Lancia Integrale - The Peter Collins & Paul The Crowood Complete Story Baker Press 2003 Lancia Le ammiraglie dall'Aurelia alla Thesis Quattroruote Ed Domus 2002 Unique Motor Lancia Stratos Compilation Books Lancia – Flavia – Flaminia - Unique Motor -

Download PDF Lancia Aurelia GT 250

1955 Lancia Aurelia GT 250 B20 - Series 4 € 147,500.00 - Lovely example with a nice patina - Delivered new in England (RHD) - New carpets, new Nardi steering wheel,.. - Restored in the Netherlands - Belgian registration - Lancia Certificate! The Lancia Aurelia B20 The Italian economy recovered slowly after WOII; and Jano's Aurelia (B10) design was quite the revolutionary thing back in 1949. The combination of luxury, power, looks and presence were really something! The first car with a mass produced full alloy V6 engine, in board brakes, monocoque construction and a very slick, aerodynamic design. Pinin Farina took care of the coupe design - called B20 - resulting in the first ever use of the GT or Gran Turismo name! The Aurelia was very successful with privateers in motor racing. In 1951 a stock Aurelia finished 2nd in the legendary Mille Miglia race! During the 8 years of production, the Aurelia underwent many updates, so called Series. In these, the Serie 4 is recognized as the biggest evolution because of the de Dion suspension and more powerful engine. The Aurelia was a succes in England as well, despite being more expensive than a Bentley at the time! Lord March even said: "Definitely one of my favorite cars of all time!" Our Aurelia B20 GT 250 The series 4 we're offering is equipped with the upgraded suspension and the more powerful 2.5 V6 delivering 118hp. They built 573 examples in 1954, over a total of 3001 Aurelia's. This particular one was restored in the Netherlands, beginning of 2000, and is finished in a beautiful baby blue called Azzuro Agnano-Celeste. -

Lancia Torque

Issue No. 38 May–June 2018 Wintersun will soon be here… 6–9 July 2018 President’s Report With Winter now officially upon us, Maserati models being refused entry it’s a great time to enjoy that non- to Australia to attend a recent airconditioned (but much more fun International Maserati Meeting. Lancia Club Queensland Inc to drive than a ‘modern’) Lancia in For the private owners of those cars, P.O.Box 25 the garage. the refusal must have been Nerang QLD 4211 devastating and extremely annoying. Some of us have already started Think of the cost and huge www.shannons.com.au/club/carclubs doing exactly this, judging from the disappointment. /lancia-club-qld/ reports and photos appearing in this issue regarding our Autumn Lockyer I’m afraid it puts Australia in a very https://www.facebook.com/search/t Valley Drive in April and the David bad light and will have a lasting and op/?q=lancia%20club%20of%20queen sland%20inc Hack Classic Meet at Toowoomba detrimental effect on historic car Airfield in May. ownership of all classes in this country. Who is going to risk President Now comes Wintersun 2018 and importing a classic car? And who is Paul Doumany Giro di Nord Otto which I’m proud going to risk temporarily sending 0412-245 452 [email protected] to report is a virtual ‘sell out’. Yes their classic car overseas when folks, the only accommodation now there’s no guarantee it will be Vice-President available for the 3 nights of the permitted to return to Australia? Dave White Wintersun long weekend would be 0407-550 610 elsewhere in Stanthorpe from where Better rules of a precise nature are [email protected] arrangements have already been clearly required and a more practical made. -

September 2013 Price List

PRICE LIST Brooklands Books SEPTEMBER 2013 Page 1 - 9 Road Test and Workshop Manual Books Page 9 - 10 Racing Books and Motorcycle Books Page 10 - 11 Redline Books Page 11 Miscellaneous Books Page 11 - 12 Iconografix Books Brooklands Books Ltd. PO Box 146, Cobham, Surrey KT11 1LG, England Phone: 01932 865051 Fax: 01932 868803 E-mail: [email protected] www.brooklands-books.com Brooklands Books Australia 3/37-39 Green Street, Banksmeadow, NSW 2019, Australia Telephone: 2 9695 7055 Fax: 2 9695 7355 www.renniks.com Motorbooks, Quayside Publishing Group 400 First Avenue North, Minneapolis, MN 55401 USA Phone: (1-800) 612 344 8100 Fax: (612) 344-8691 E-mail: [email protected] www.motorbooks.com Cartech Books 39966 Grand Avenue North Branch, MN 55056 USA Phone: (1-800) 551 4754 Fax: 651-277-1203 E-mail: [email protected] www.cartechbooks.com Find us on Facebook QTY CODE ISBN No. TITLE PART No. £ QTY CODE ISBN No. TITLE PART No. £ ABARTH A20WH 9781855202818 A/H Sprite Mk 2, 3 & 4 and Midget AKD4021 32.95 ABARP 9781855209299 Abarth Road Test Portfolio 1950-1971 24.95 Owners Handbooks FIABRP 9781855209305 Fiat Abarth Road Test Portfolio 1972-1987 19.95 A136HH 9781869826352 Austin-Healey 100 97H996E 15.95 AC A135HH 9781870642903 Austin-Healey 100/6 97H996H 15.95 AC11SRP 9781855209596 AC Cars 1904-2011 45.95 A137HH 9781869826369 Austin-Healey 3000 Mk 1 & 2 AKD3915A 15.95 ACA53RP 9781855209787 AC Ace, Aceca, Greyhound 1953-1962 19.95 A138HH 9781869826376 Austin-Healey 3000 Mk 3 AKD4094B 15.95 Now Available A15HH 9780948207945 -

Air Apparent

LANCIA AURELIA B52 SPIDER Air apparent After lying dormant for 30 years, this ultra-rare, aerodynamically streamlined Lancia Spider was brought back to life by a painstaking decade-long restoration WORDS Massimo Delbò // PHOTOGRAPHY Dirk De Jager 144 AUGUST 2014 OCTANE OCTANE AUGUST 2014 145 LANCIA AURELIA B52 SPIDER OLLOWING THE as having entered production on Tuesday 1 end of the Second July 1952, with all work (including a test drive ‘It’s natural that World War, Italy’s car of the bare rolling chassis) completed at the industry entered a Lancia factory by Friday of the same week. each car should renaissance. After all Pinin Farina’s archive, damaged by a fire, does the destruction during not report the early history of this car nor any look different hostilities, new ideas of its sisters, but Lancia’s archive reports the came from research steering box number (7549), the front from the next. carried out by the suspension number (7269) and the differential military, and they revolutionised the car world. number (7067), plus the ‘chassis’ number (526). Chassis no 1052 FThe great new frontier was aerodynamics: This last number needs some clarification: most of the automotive engineers of the period for cars built by Lancia or by outside presents several were arriving from aviation, and streamlining coachbuilders under the control of Lancia, it was the new keyword. identified the bodyshell or, for B50s through unique touches’ In Turin, Battista ‘Pinin’ Farina, thanks to his B56s, the bare platform. What we today call pre-war creations, was already a well-known the ‘chassis number’ was mentioned as such name in coachbuilding. -

Catalogo Generale Lancia Rev. 06.2021.Xlsx

ROBUSTELLI S.r.l. STAMPAGGIO GOMMA AD INIEZIONE Via del Lavoro, 9 -22079 VILLA GUARDIA ( Como ) Tel . +031 480529 Fax +031 481529 www.robustelli.it [email protected] CATALOGO GENERALE LANCIA Lancia APPIA Lancia APRILIA Lancia AURELIA Lancia BETA Lancia DELTA Lancia FLAMINIA Lancia FLAVIA Lancia FULVIA Lancia GAMMA Lancia PRISMA i particolari da noi forniti NON sono originali ma con essi, perfettamente intercambiabili ROBUSTELLI SRL Via del Lavoro, 9 -22079 VILLA GUARDIA ( Como ) Tel . +031 480529 Fax +031 481529 www.robustelli.it [email protected] LANCIA APPIA CODICE : L4 adatt. OEM 2174093 Guarnizione vaschetta olio freni - Brake Fluid Tank Seal Lancia APPIA Lancia FLAVIA LANCIA FLAMINIA CODICE : L18 Guarnizione/membrana rubinetto riscaldamento Top Heating Seal Fulvia 1' serie, Flaminia , Flavia , Aurelia FIAT 1100 - A.R. Giulia / Giulietta Lancia Appia Foro- Hole Ø 15 CODICE : L19 Guarnizione/membrana rubinetto riscaldamento Top Heating Seal Fulvia 1' serie, Flaminia , Flavia , Aurelia FIAT 1100 - A.R. Giulia / Giulietta Lancia Appia Foro- Hole Ø 10 CODICE : L27 adatt. OEM 82136813 Supporto MOTORE Superiore per LANCIA Appia Superior Engine Mounts in rubber for LANCIA Appia 1' e 2' serie / 1' and 2' series n.2 pezzi/pieces each car CODICE : L28 adatt. OEM 82136815 Supporto MOTORE Inferiore per LANCIA Appia Inferior Engine Mounts in rubber for LANCIA Appia 2' serie / 2' series n.4 pezzi/pieces each car CODICE: L37 adatt. OEM: OEM: 82137567 82137567 Centratore protezione Albero di trasmissione Rubber protections for drive shaft Lancia Aurelia (dal '56 al'58 3pz. Macchina) Lancia Appia (2 pz. Per macchina) Lancia Flaminia (3 pz. Per macchina) 2 ROBUSTELLI SRL Via del Lavoro, 9 -22079 VILLA GUARDIA ( Como ) Tel .