Cash Feasibility Assessment 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEEKLY REPORT 26 March – 1 April 2021

WEEKLY REPORT 26 March – 1 April 2021 KEY DYNAMICS Government fuel and healthcare 2 Government fuel crisis intensifies ........................................................... 2 Government’s additional measures to combat COVID-19 ............ 3 ISIS destabilizes northeast ......................................................................................... 6 ISIS threats cause resignation of council members ........................... 6 SDF and IC search and arrest campaign in Al Hol camp .................. 6 Access and services in northern Syria ...................................................................... 7 Syrian government seeks commercial crossings in north ............... 7 The return of water provision in Azaz city ........................................... 9 Cover photo: SDF Raids in Al-Hol camp (Source: AFP/The National) MERCY CORPS HUMANITARIAN ACCESS WEEKLY REPORT, 26 March – 1 April 2021 1 Government fuel and healthcare Governorate fuel allocations significantly reduced Government fuel crisis intensifies The executive councils in several governorates announced the reduction of fuel allocations and Fuel scarcity has reached an all-time high in additional administrative measures to cope with Syrian government-held areas, causing gas the unprecedented scarcity of fuel. At the end of stations to close down, extensive queuing and March, the central fuel councils in Hama, shortages throughout the governorates. In As- Tartous, Dar’a and Damascus imposed a limit on Sweida, only five stations remain open to serve private vehicles of 20 liters per week on benzene the entire population, while in Rural Damascus, Additionally, fuel allocations in Hama and local sources report queues up to one kilometer Damascus were reduced for both petrol and long, with citizens waiting two to three days in diesel; Hama’s allocations went from 14 to 10 front of gas stations, some resorting to sleeping trucks for petrol and 14 to 6.5 for diesel and in their cars. -

Impact of Ceasefire on Civilians in Areas of Aleppo, Idlib, and Rural Damascus Held by Armed Opposition Groups, 20-24 January 2017

Impact of Ceasefire on Civilians in areas of Aleppo, Idlib, and Rural Damascus held by Armed Opposition Groups, 20-24 January 2017 Background agreement; rather, it is intended to measure the effect markets, schools, and workplaces improved. In of such agreement on civilians’ lives. areas which experienced physical threats due to A ceasefire agreement entered into effect in Syria on shelling or air strikes, on the other hand, key December 30, 2016. The effort was brokered by Turkey Methodology informants expressed constant fear, which and Russia and unanimously supported by the United From January 20-24, 2017, 7 members of the affected their freedom of movement and by Nations Security Council on December 31.1 According Protection Cluster, including 5 Syrian NGOs and 2 extension access to health services, schools, and to the terms of the ceasefire it applies to “all groups of international NGOs, conducted 218 key informant (KI) workplaces. opposing sides” and excludes areas of combat interviews. This report owes greatly to the efforts of operations against ISIL and the Nusra Front.2 humanitarian workers on the ground inside northern The main reason cited for decreases in access to Objectives Syria. Partners conducted interviews in areas of Idlib markets was physical danger, in addition to governorate (117 interviews total in Al Ma’ra, Ariha, inability to pay for goods, lack of goods, and lack of This assessment of the Impact of Ceasefire on Civilians Harim, and Idlib districts), Aleppo governorate (75 transport. For increases, the feeling of safety was in areas of Aleppo, Idlib, and Rural Damascus held by interviews total in in Azaz and Jebel Saman districts); the reason. -

A/HRC/40/70 Advance Edited Version

A/HRC/40/70 Advance Edited Version Distr.: General 31 January 2019 Original: English Human Rights Council Fortieth session 25 February–22 March 2019 Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic*, ** Summary Extensive military gains made by pro-government forces throughout the first half of 2018, coupled with an agreement between Turkey and the Russian Federation to establish a demilitarized zone in the north-west, led to a significant decrease in armed conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic in the period from mid July 2018 to mid January 2019. Hostilities elsewhere, however, remain ongoing. Attacks by pro-government forces in Idlib and western Aleppo Governorates, and those carried out by the Syrian Democratic Forces and the international coalition in Dayr al-Zawr Governorate, continue to cause scores of civilian casualties. In the aftermath of bombardments, civilians countrywide suffered the effects of a general absence of the rule of law. Numerous civilians were detained arbitrarily or abducted by members of armed groups and criminal gangs and held hostage for ransom in their strongholds in Idlib and northern Aleppo. Similarly, with the conclusion of Operation Olive Branch by Turkey in March 2018, arbitrary arrests and detentions became pervasive throughout Afrin District (Aleppo). In areas recently retaken by pro-government forces, including eastern Ghouta (Rif Dimashq) and Dar’a Governorate, cases of arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance were perpetrated with impunity. After years of living under siege, many civilians in areas recaptured by pro-government forces also faced numerous administrative and legal obstacles to access key services. -

THE FUEL SECTOR of NORTHWEST SYRIA Untangling the Web for Humanitarians DECEMBER 2019

THE FUEL SECTOR OF NORTHWEST SYRIA Untangling the web for humanitarians DECEMBER 2019 1 / 22 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The fuel sector in Syria has changed radically since the outbreak of the Syrian conict in 2011. In the past nine years, the sector has transitioned from a market strictly regulated by the Syrian government, to one completely driven by the forces of demand, supply and the status of supply lines. As the conict erupted the Syrian Petroleum Storage and Distribution Company (SADCOB), the sole distributor of gasoline, diesel and gas in Syria, suspended operations and withdrew from areas beyond the Government of Syria’s control. Domestic oil reserves in the northeast were separated from the distribution network based in Damascus. The nation’s infrastructure and economy, 95% reliant on fossil fuels prior to 2011, was left at the whim of smuggling across lines of control, cross-border trade navigating extensive sanctions, and ongoing changes in suppliers, leading to signicant supply and price uctuations. The fuel sector in northwest Syria epitomised this volatility. Longstanding public dissatisfaction with fuel prices, poor fuel quality, and inconsistent availability provided the Syrian Salvation Government an opportunity to intervene in the lucrative sector. Less than six months after the establishment of the Salvation Government, the Watad petroleum company emerged. Since 2018, Watad fuel company, Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), and the Salvation Government 2 / 22 have worked together to gain complete control of the fuel sector in northwest Syria. Not only is Watad the only company permitted to import petroleum into the area from Turkey, it has also worked with HTS to consolidate control of the crossline and smuggled fuel trade, from both Government of Syria and Kurdish self-administration (KSA) areas. -

Building Legitimacy Under Bombs: Syrian Local Revolutionary Governance’S Quest for Trust and Peace

BUILDING LEGITIMACY UNDER BOMBS: SYRIAN LOCAL REVOLUTIONARY GOVERNANCE’S QUEST FOR TRUST AND PEACE Nour Salameh ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Syrien, 1. Quartal 2020: Kurzübersicht Über Vorfälle Aus Dem Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project

SYRIEN, 1. QUARTAL 2020: Kurzübersicht über Vorfälle aus dem Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) zusammengestellt von ACCORD, 23. Juni 2020 Anzahl der berichteten Vorfälle mit mindestens einem Anzahl der berichteten Todesopfer Todesopfer Staatsgrenzen: GADM, November 2015a; Verwaltungsgliederung: GADM, November 2015b; Vor- fallsdaten: ACLED, 20. Juni 2020; Küstenlinien und Binnengewässer: Smith und Wessel, 1. Mai 2015 SYRIEN, 1. QUARTAL 2020: KURZÜBERSICHT ÜBER VORFÄLLE AUS DEM ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) ZUSAMMENGESTELLT VON ACCORD, 23. JUNI 2020 Inhaltsverzeichnis Konfliktvorfälle nach Kategorie Anzahl der berichteten Todesopfer 1 Anzahl der Vorfälle mit Anzahl der Anzahl der Anzahl der berichteten Vorfälle mit mindestens einem Todesopfer 1 Kategorie mindestens Vorfälle Todesopfer einem Konfliktvorfälle nach Kategorie 2 Todesopfer Entwicklung von Konfliktvorfällen von März 2018 bis März 2020 2 Explosionen / Fernangriffe 2213 324 1109 Kämpfe 859 354 1699 Methodologie 3 strategische Entwicklungen 340 0 0 Berichtete Konfliktvorfälle nach Provinz 4 Gewalt gegen Zivilpersonen 256 163 252 Proteste 63 0 0 Lokalisierung der Konfliktvorfälle 4 Ausschreitungen 9 2 4 Hinweis 8 Gesamt 3740 843 3064 Die Tabelle basiert auf Daten von ACLED (verwendete Datensätze: ACLED, 20. Juni 2020). Entwicklung von Konfliktvorfällen von März 2018 bis März 2020 Das Diagramm basiert auf Daten von ACLED (verwendete Datensätze: ACLED, 20. Juni 2020). 2 SYRIEN, 1. QUARTAL 2020: KURZÜBERSICHT ÜBER VORFÄLLE AUS DEM ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) ZUSAMMENGESTELLT VON ACCORD, 23. JUNI 2020 Methodologie Die beiden oben dargestellten Karten dienen dazu, die Anzahl berichteter Todes- opfer (die Schätzungen beinhalten kann) mit der Anzahl an Vorfällen mit mindes- Die Daten, die in diesem Bericht verwendet werden, stammen vom Armed Conflict tens einem berichteten Todesopfer zu vergleichen. -

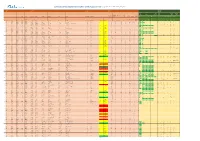

CCCM Cluster IDP Sites Integrated Monitoring Matrix (ISIMM), August 2020/ 2020 بأ ، ﺣزﺎﻨﻟا تﺎﻌﻤ

ﻣﺼﻔﻮﻓﺔ اﻟﻤﺮاﻗ�ﺔ اﻟﻤﺘ�ﺎﻣﻠﺔ ﻟﺘﺠﻤﻌﺎت اﻟﻨﺎزﺣ���، أب CCCM Cluster_ IDP Sites Integrated Monitoring Matrix (ISIMM), August 2020/ 2020 Total PCODES LOCATION SITE DETAILS Number of SECTORAL ANALYSIS ﺗﺤﻠ�ﻞ اﻟﻘﻄﺎﻋﺎت IDPs ﺗﻔﺎﺻ�ﻞ اﻟﻤﻮﻗﻊ اﻟﻤﻮﻗﻊ اﻟ�ﻮد February Shelter& WASH PROTECT FSL ION HEALTH EDUCATION اﻟﻤ�ﺎە / NFI اﻷﻣﻦ اﻟﻐﺬا��� اﻟﺘﻌﻠ�ﻢ ﻟﺼﺤﺔ اﻟﺤﻤﺎ�ﺔ واﻟ�ف اﻟﻤﺄوى وﺳ�ﻞ اﻟﻌ�ﺶ Boys (Children Education اﺳﺎس اﻟﻨ�ع اﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋ�ﺔ اﻟﺼ�� واﻟﻤﻮاد ﻏ�� اﻟﻤﻮاد اﻟﻐ�� Protectio اﻟﻌﻨﻒ ﻋ� Protectio Health Sanitatio زاﻟﺔ اﻻﻧﻘﺎذ Removal Violence ﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎﻋ�ﺔ اﻻﺟﺮاءات Gender اﻟﺼﺤ�ﺎت ﻻﺟﺘﻤﺎ�� Girls (Children under 18) Women (Female Men- (Male Total Special Needs اﻟﻤﺘﻌﻠﻘﺔ Shelter Waste اﻟﺤﻤﺎ�ﺔ Based Action Water �ﺎﻻﻟﻐﺎم اﻟﺼﺤﺔ Mine ﺣﻤﺎ�ﺔ Child ﻟﺘﻌﻠ�ﻢ اﻟﻄﻌﺎم ﻏﺬاﺋ�ﺔ ﻟﻤﺄوى اﻟﻄﻔﻞ Food ذوي اﻻﺣﺘ�ﺎﺟﺎت adults) adults) Individuals Total Families اﻻوﻻد دون ﺳﻦ (PCODE PCODE Governorate District Sub District Community Cluster Site Name Type of Location* Shelter Details under 18 اﻟﻤﺎء NFI ** n n n اﻟﺨﺎﺻﺔ ﻣﺠﻤ�ع اﻟﻌﻮاﺋﻞ ﻣﺠﻤ�ع اﻻﻓﺮاد اﻟﺮﺟﺎل اﻟ�ﺎﻟﻐ��� اﻟ�ﺴﺎء اﻟ�ﺎﻟﻐﺎت 18 اﻟﺒﻨﺎت دون ﺳﻦ 18 وﺛﺎﺋﻖ اﻟﻤﻠ��ﺔ / HLP ﺗﻔﺎﺻ�ﻞ اﻟﻤﺄوى ﻧ�ع اﻟﻤﻮﻗﻊ اﺳﻢ اﻟﻤﻮﻗﻊ اﻟ�ﺘﻠﺔ / اﻟﻤﺠﻤﻮﻋﺔ اﻟﻘ��ﺔ اﻟﻨﺎﺣ�ﺔ اﻟﻤﻨﻄﻘﺔ اﻟﻤﺤﺎﻓﻈﻪ S.N. PCODE Admin1 PCODE Admin2 PCODE Admin3 Admin4 Sites Waste_Removal Sanitation Education Special Needs Health Shelter Water اﻟﺼﺤﺔ اﻟﺘﻌﻠ�ﻢ Food GBV ذوي اﻻﺣﺘ�ﺎﺟﺎت _PCODE_ Total_Individua Total_Families PRT MA NFI ** CP اﻟﺨﺎﺻﺔ SN Admin1 Admin2 Admin3 Admin4 Sites Governorate District Sub_District Community Cluster Site_Name Type_of_Location Shelter_Details Land Type HLP Status Girls_June Boys_June Women_June -

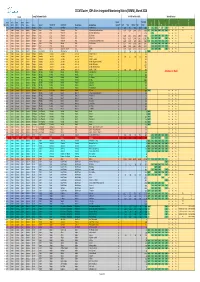

201603 Cccm Cluster Isimm M

CCCM Cluster_ IDPs Sites Integrated Monitoring Matrix (ISIMM), March 2016 PCODES Camp/ Settlement Details # of IDPs in March 2016 Sectoral Analysis Protection Sanitation Education Health** Removal Shelter Waste Water Food PCODE PCODE PCODE PCODE PCODE Type of Total IDPs GBV NFI Admin1 Admin2 Admin3 Admin4 Camps CP No. Gov. District Sub District Community Cluster Name Location Name Location* Girls Boys Women Men in Mar. 1 SY02 SY0203 SY020300 C1371 CP000002 Aleppo Afrin Afrin Baselhaya Afrin Roubar Camp IS 848 841 765 546 3,000 50% 100% 100% 20% 50% 100% No No No MC 2 SY02 SY0204 SY020400 C1566 CP000007 Aleppo A'zaz A'zaz Shamarin Azaz Al Harameen (and extensions) TC 3,421 3,086 2,009 1,453 9,969 75% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Yes No No MC 3 SY02 SY0204 SY020400 C1566 CP000278 Aleppo A'zaz A'zaz Shamarin Azaz Al Resalah (Al Armuda) IS 1,740 100% No No No 4 SY02 SY0204 SY020400 C1566 CP000003 Aleppo A'zaz A'zaz Shamarin Azaz Bab Al Iman IS 2,589 2,361 1,523 1,143 7,616 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% No No No Yes 5 SY02 SY0204 SY020400 C1566 CP000004 Aleppo A'zaz A'zaz Shamarin Azaz Bab Al Noor IS 4,169 3,723 2,448 1,752 12,092 41% 100% 100% 100% 100% Yes No Yes Yes 6 SY02 SY0204 SY020400 C1566 CP000009 Aleppo A'zaz A'zaz Shamarin Azaz Shamarin (Dhahiat Al‐Shuhada) IS 1,641 2,170 997 1,056 5,864 80% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% No No No 7 SY02 SY0204 SY020400 C1561 CP000005 Aleppo A'zaz A'zaz Salama Azaz Bab Al Salame IS 2,817 2,569 1,658 1,243 8,287 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% Yes Yes Yes Yes 8 SY02 SY0204 SY020400 C1561 CP000008 Aleppo A'zaz A'zaz Salama -

IDP Locations - As of 29 February 2016 Produc Tion Date : 03 Marc H 2016

SY RIA - Disp lac em ents from Alep p o Governorate (1 Feb 2016 to 29 Feb 2016) Hum anitarian Purp oses Only IDP Locations - As of 29 February 2016 Produc tion date : 03 Marc h 2016 BULBUL SHARAN Raju راﺟو!) RAJU Shamarin Bab Al Iman Ekkdeh Talil Shamarin Krum Bab Al Noor ² Elsham Dhahiat Hiwar Kalas Yarobiyeh GHANDORAH Al-Shuhada Zayzafun Bab Al Shmarekh Al Harameen - Ekdeh Baraghideh Salame Sharan Kafr Kafrshush A'ZAZ ﺷران (! Maarin Tatiyeh Barja Salama Sujjo Jdideh Ar-Ra'ee اﻟراﻋ ﻲ Nayara SURAN (! Mreigel AR-RA'EE Ferziyeh Albil Rael Odaya Azaz (! Niddeh MA'BTALI Yahmul Thaheriya Shweirin Azaz AGHTRIN Sijraz Azaz Jarez Suran أﻋزاز Maab atli ﺻوران Dweibeq !) اﻟﻣﻌﺑطﻠ ﻲ (! Kafr Kafra Ehteimlat Shawarghet Kafr Kalbein Eljoz Maraanaz Khasher Al-Malikeyyeh SHEIKH Khadraa Kaljibrin EL-HADID Mreimin Shawarghet Tal Afrin Elarz Nireh Tawil Hawa Manaq Sheikh Enab (! Afrin Khaldiyet Akhtrein El-Hadid Kafrshil (! أﺧﺗرﯾن Afrin ﻋﻔرﯾن Marata ﺷﯾﺦ اﻟﺣدﯾد!) Tharifa Mare' ﻣﺎرع Jalbal Bablit Tall Refaat (! ﺗل رﻓﻌ ت!) - Abin Kafr Qarzihel Roubar Efrin A'RIMA Batra Ein Dara Camp Bteita Baselhaya Kawkabeh AFRIN Bseileh Oqayba TALL REFAAT Tellef Basuta Zahrat MARE' Ziyara Elhayat Kimar Kafir Afrin JANDAIRIS Kafr Zeid Burj Abdallah Jandairis ﺟﻧدﯾر س (! AL BAB T U R K E Y Brad N ab ul Al Bab ﻧﺑل Sheikh (! اﻟﺑﺎب Eldeir Ghazawiyet (! Afrin Baee Eskan NABUL Tadaf Burj ﺗﺎدف!) Basufan Haydar Bashkwi Kabashin Samaan Hayyan Atmeh Fafertein Tamura Qassioun Atma Selwa Shabab Al Qah Khayr 3 Shuhdaa TADAF Abdeen Zarzita Daret Kafrantin Andan Haritan ﺣرﯾﺗﺎن Tajammu Azza -

Wheat-To-Bread Processing Facility Mapping and Need Assessment Study Northwest Syria December 2019 Table of Contents

Wheat-to-Bread Processing Facility Mapping and Need Assessment Study Northwest Syria December 2019 Table of contents 1. Introduction 4 Study Objectives 4 Geographical Coverage of the Study 4 2. Methodology 5 3. Bakery Mapping 6 Sample 6 Bakery operational status 6 Bakery Ownership 7 Bakery Machinery and Building Status 9 Bakeries Functionality 10 Rehabilitation needs 12 Types of Produced Bread 13 Bakeries Production Inputs 14 Bakeries Accessibility and security Situation 16 Bakery production capacity against the subdistrict population 17 4. Mills Mapping 18 Sample 18 Mill facility location and operational status 18 Sources of wheat grain for the surveyed mills 19 Constraints to increased mill production 19 Current structure and operational capacity of mills 20 Mills flour production 20 Support required to improve mill production 21 5. Silos Mapping 22 Sample 22 Silos facility location and operational status 22 Source of wheat and support required to improve wheat storage facilities 24 6. Discussions 25 Bakeries 25 Mills 26 Silos 27 7. Recommendations 27 Further studies 27 Implications for programming 27 List of figures Figure 1: Status of Bakeries in NW Syria 6 Figure 2: Bakery status at subdistrict level in NW Syria 7 Figure 3: Bakery ownership styles in NW Syria 7 Figure 4: Management authority in NW Syria 9 Figure 5: Machines availability 10 Figure 6: Daily Production of Bread per District in NW Syria 10 Figure 7: Bakeries Functionality 11 Figure 8: Bakery need in NW Syria 13 Figure 9: Production for each tyoe if bread 13 Figure 10: -

Impact of Ceasefire on Civilians in Areas of Aleppo, Idlib, and Rural Damascus Held by Armed Opposition Groups, 20-24 January 2017

Impact of Ceasefire on Civilians in areas of Aleppo, Idlib, and Rural Damascus held by Armed Opposition Groups, 20-24 January 2017 Background agreement; rather, it is intended to measure the effect markets, schools, and workplaces improved. In of such agreement on civilians’ lives. areas which experienced physical threats due to A ceasefire agreement entered into effect in Syria on shelling or air strikes, on the other hand, key December 30, 2016. The effort was brokered by Turkey Methodology informants expressed constant fear, which and Russia and unanimously supported by the United From January 20-24, 2017, 7 members of the affected their freedom of movement and by Nations Security Council on December 31.1 According Protection Cluster, including 5 Syrian NGOs and 2 extension access to health services, schools, and to the terms of the ceasefire it applies to “all groups of international NGOs, conducted 218 key informant (KI) workplaces. opposing sides” and excludes areas of combat interviews. This report owes greatly to the efforts of operations against ISIL and the Nusra Front.2 humanitarian workers on the ground inside northern The main reason cited for decreases in access to Objectives Syria. Partners conducted interviews in areas of Idlib markets was physical danger, in addition to governorate (117 interviews total in Al Ma’ra, Ariha, inability to pay for goods, lack of goods, and lack of This assessment of the Impact of Ceasefire on Civilians Harim, and Idlib districts), Aleppo governorate (75 transport. For increases, the feeling of safety was in areas of Aleppo, Idlib, and Rural Damascus held by interviews total in in Azaz and Jebel Saman districts); the reason. -

SYRIA - from Aleppo Governorate Humpurposes Anitarian Only IDP Locations - As of 17 March 2016 Productionmarch30 2016: Date

S Y R IA - DisplacementsSYRIA - from Aleppo Governorate HumPurposes anitarian Only IDP Locations - As of 17 March 2016 ProductionMarch30 2016: date Raju BULBUL Gh andura LOWER SHYOOKH اﻟﻐﻧدورة)! راﺟو)! Bab Al Hiwar JARABLUS Iman Kalas Shamarin Ekkdeh Big Arab Oshrieh Little Krum Talil Elsham Hasan Hamam RAJU Shamarin Zayzafun Yarobiyeh GHANDORAH A'ZAZ Shmarekh Dhahiat - Ekdeh Al Harameen Al-Shuhada Baraghideh Dadat Kafrshush SHARAN Bab Al Salame Kafr AGHTRIN Rafeeah SURAN Kherbet Arnabiet Jota !( Maarin Sujjo Tatiyeh Barja Saan Manilla Jdideh Ar-Ra'ee Hamran Elhsan Doshan Salama Um Jlud Elghazal - Kherbet Asaad Kabiret Qaber اﻟراﻋﻲ Sharan ² !( Buz Kij Massi Um Adaset Zornaqal Imu ﺷران Nayara Manbaj - Lower Mreigel AR-RA'EE Elfarat Qabab Twal Bashli Kherbet Boyer Majra Ferziyeh Albil Middle Bonyeh - Rael Nafakh Mashrafet Safi Anzawiyeh Odaya Elbweir MENBIJ Majra Qarajleh Um Edam Khirfan Azaz Tal Manbaj !( Shweirin MA'BTALI Niddeh Yahmul Thaheriya Rafei Azaz Dandaniya Bir Sijraz Azaz Farat Hudhud Little Jarez Jamusiyeh Tal Shweihet Ein Big Kello أﻋزاز Maabatli Suran Hayyeh Jeb Kheznawi Elnakhil Hayyeh Kafra !( Dweibeq Akhdar اﻟﻣﻌﺑطﻠﻲ Suran Ehteimlat Upper ﺻوران Kafr )! Elarus Jeb Shawarghet Kafr Kalbein Sayada Mahsana - Majra Tal Eljoz Maraanaz Sheikh Elqader Khasher Bak Weiran Asaliyeh Yasti SHEIKH EL-HADID Al-Malikeyyeh Yehya Mankubeh Khadraa Karsan Kaljibrin Middle Big Omriyeh Rasm Mreimin Shawarghet Warideh Madneh Elmashrafeh Ratwaniyeh Tal Afrin Kherbet Menb ij Hawa Elarz !( Hajar Menbij ﻣﻧﺑﺞ Nireh Tawil Manaq Elsheyab Sghireh Little