A/HRC/40/70 Advance Edited Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEEKLY REPORT 26 March – 1 April 2021

WEEKLY REPORT 26 March – 1 April 2021 KEY DYNAMICS Government fuel and healthcare 2 Government fuel crisis intensifies ........................................................... 2 Government’s additional measures to combat COVID-19 ............ 3 ISIS destabilizes northeast ......................................................................................... 6 ISIS threats cause resignation of council members ........................... 6 SDF and IC search and arrest campaign in Al Hol camp .................. 6 Access and services in northern Syria ...................................................................... 7 Syrian government seeks commercial crossings in north ............... 7 The return of water provision in Azaz city ........................................... 9 Cover photo: SDF Raids in Al-Hol camp (Source: AFP/The National) MERCY CORPS HUMANITARIAN ACCESS WEEKLY REPORT, 26 March – 1 April 2021 1 Government fuel and healthcare Governorate fuel allocations significantly reduced Government fuel crisis intensifies The executive councils in several governorates announced the reduction of fuel allocations and Fuel scarcity has reached an all-time high in additional administrative measures to cope with Syrian government-held areas, causing gas the unprecedented scarcity of fuel. At the end of stations to close down, extensive queuing and March, the central fuel councils in Hama, shortages throughout the governorates. In As- Tartous, Dar’a and Damascus imposed a limit on Sweida, only five stations remain open to serve private vehicles of 20 liters per week on benzene the entire population, while in Rural Damascus, Additionally, fuel allocations in Hama and local sources report queues up to one kilometer Damascus were reduced for both petrol and long, with citizens waiting two to three days in diesel; Hama’s allocations went from 14 to 10 front of gas stations, some resorting to sleeping trucks for petrol and 14 to 6.5 for diesel and in their cars. -

The Illegal Excavation and Trade of Syrian Cultural Objects

JOURNAL OF FIELD ARCHAEOLOGY, 2018 VOL. 43, NO. 1, 74–84 https://doi.org/10.1080/00934690.2017.1410919 The Illegal Excavation and Trade of Syrian Cultural Objects: A View from the Ground Neil Brodiea and Isber Sabrineb aUniversity of Oxford, Oxford, UK; bUniversitat de Girona, Girona, Spain ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The illegal excavation and trade of cultural objects from Syrian archaeological sites worsened Syria; looting; cultural markedly after the outbreak of civil disturbance and conflict in 2011. Since then, the damage to objects; coins; policy archaeological heritage has been well documented, and the issue of terrorist funding explored, but hardly any research has been conducted into the organization and operation of theft and trafficking of cultural objects inside Syria. As a first step in that direction, this paper presents texts of interviews with seven people resident in Syria who have first-hand knowledge of the trade, and uses information they provided to suggest a model of socioeconomic organization of the Syrian war economy regarding the trafficking of cultural objects. It highlights the importance of coins and other small objects for trade, and concludes by considering what lessons might be drawn from this model to improve presently established public policy. Introduction conflictantiquities.wordpress.com/). Nevertheless, most of what is known about illegal excavation and trade inside Like that of many countries in the Middle East and North Syria comes from some of the better media reporting, Africa (MENA) region, for the past few decades the archaeo- which has on occasion managed to access people with first- logical heritage of Syria has been robbed of cultural objects for hand knowledge or experience of the problem. -

International Activity Report 2017

INTERNATIONAL ACTIVITY REPORT 2017 www.msf.org THE MÉDECINS SANS FRONTIÈRES CHARTER Médecins Sans Frontières is a private international association. The association is made up mainly of doctors and health sector workers, and is also open to all other professions which might help in achieving its aims. All of its members agree to honour the following principles: Médecins Sans Frontières provides assistance to populations in distress, to victims of natural or man-made disasters and to victims of armed conflict. They do so irrespective of race, religion, creed or political convictions. Médecins Sans Frontières observes neutrality and impartiality in the name of universal medical ethics and the right to humanitarian assistance, and claims full and unhindered freedom in the exercise of its functions. Members undertake to respect their professional code of ethics and to maintain complete independence from all political, economic or religious powers. As volunteers, members understand the risks and dangers of the missions they carry out and make no claim for themselves or their assigns for any form of compensation other than that which the association might be able to afford them. The country texts in this report provide descriptive overviews of MSF’s operational activities throughout the world between January and December 2017. Staffing figures represent the total full-time equivalent employees per country across the 12 months, for the purposes of comparisons. Country summaries are representational and, owing to space considerations, may not be comprehensive. For more information on our activities in other languages, please visit one of the websites listed on p. 100. The place names and boundaries used in this report do not reflect any position by MSF on their legal status. -

S/2019/321 Security Council

United Nations S/2019/321 Security Council Distr.: General 16 April 2019 Original: English Implementation of Security Council resolutions 2139 (2014), 2165 (2014), 2191 (2014), 2258 (2015), 2332 (2016), 2393 (2017), 2401 (2018) and 2449 (2018) Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is the sixtieth submitted pursuant to paragraph 17 of Security Council resolution 2139 (2014), paragraph 10 of resolution 2165 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2191 (2014), paragraph 5 of resolution 2258 (2015), paragraph 5 of resolution 2332 (2016), paragraph 6 of resolution 2393 (2017),paragraph 12 of resolution 2401 (2018) and paragraph 6 of resolution 2449 (2018), in the last of which the Council requested the Secretary-General to provide a report at least every 60 days, on the implementation of the resolutions by all parties to the conflict in the Syrian Arab Republic. 2. The information contained herein is based on data available to agencies of the United Nations system and obtained from the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic and other relevant sources. Data from agencies of the United Nations system on their humanitarian deliveries have been reported for February and March 2019. II. Major developments Box 1 Key points: February and March 2019 1. Large numbers of civilians were reportedly killed and injured in Baghuz and surrounding areas in south-eastern Dayr al-Zawr Governorate as a result of air strikes and intense fighting between the Syrian Democratic Forces and Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. From 4 December 2018 through the end of March 2019, more than 63,500 people were displaced out of the area to the Hawl camp in Hasakah Governorate. -

Syrian Armed Opposition Powerbrokers

March 2016 Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS Cover: A rebel fighter of the Southern Front of the Free Syrian Army gestures while standing with his fellow fighter near their weapons at the front line in the north-west countryside of Deraa March 3, 2015. Syrian government forces have taken control of villages in southern Syria, state media said on Saturday, part of a campaign they started this month against insurgents posing one of the biggest remaining threats to Damascus. Picture taken March 3, 2015. REUTERS/Stringer All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2016 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2016 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella and Genevieve Casagrande MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 29 SYRIAN ARMED OPPOSITION POWERBROKERS ABOUT THE AUTHORS Jennifer Cafarella is the Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War where she focuses on the Syrian Civil War and opposition groups. Her research focuses particularly on the al Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al Nusra and their military capabilities, modes of governance, and long-term strategic vision. She is the author of Likely Courses of Action in the Syrian Civil War: June-December 2015, and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria: An Islamic Emirate for al-Qaeda. -

The Motives Behind the Establishment of the "National Army" Reserve to Turkey Abdel Nasser Hassou Introduction Popul

The Motives Behind The Establishment Of The "National Army" Reserve to Turkey Abdel Nasser Hassou Introduction Popular protests in Syria quickly turned into a bloody conflict, which has claimed nearly one million lives since 2011, due to the impact of external, international and regional factors that the Syrian arena witnessed during the past years. As the revolution turned into its military phase, it suffered from wide political and military transformations. The factions multiplied. In 2014, the number of factions was estimated at 1,000, comprising at least 100,000 Syrian and foreign fighters, and their orientations varied according to the countries that support them. The territory under their control expended (at one time it reached 70% of Syria), led to bloody conflicts between them for control of the crossings and tunnels, encapsulating those conflicts with ideology and religious fatwas, and all attempts to integrate these factions and unify them failed. In practice, the armed revolution since 2013 has not succeeded in any central operation, and has not been able to carry out any battle with strategic and tactical objectives. In fact, most of the battles it fought were in response to the regional and international struggle for the influence in the field map. The establishment of the "National Army" is a Turkish necessity The first attempt to establish a military entity after the splits in the regular army was to establish the "Free Officers Brigade", at the initiative of renegade Lieutenant Colonel Hussein Harmoush, but the attempt failed after he was arrested by Turkish intelligence and handed over to the Syrian regime on the back of his disagreement with the Turkish leaders. -

Field Developments in Idleb 51019

Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western Situation Report and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 May 2019 Aleppo Countrysides During March and April 2019 the Information Management Unit 1 Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 The Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU) aims to strengthen the decision-making capacity of aid actors responding to the Syrian crisis. This is done through collecting, analyzing and sharing information on the humanitarian situation in Syria. To this end, the Assistance Coordination Unit through the Information Management Unit established a wide net- work of enumerators who have been recruited depending on specific criteria such as education level, association with information sources and ability to work and communicate under various conditions. IMU collects data that is difficult to reach by other active international aid actors, and pub- lishes different types of information products such as Need Assessments, Thematic Reports, Maps, Flash Reports, and Interactive Reports. 2 Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western Situation Report and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 May 2019 During March and April 2019 3 Field Developments in Idleb, Northern Hama Countryside, Western and Southern Aleppo Countryside During March and April 2019 01. The Most Prominent Shelling Operations During March and April 2019, the Syrian regime and its Russian ally shelled Idleb Governorate and its adjacent countrysides of Aleppo and Hama governorates, with hundreds of air strikes, and artillery and missile shells. The regime bombed 14 medical points, including hospitals and dispensaries; five schools, including a kinder- garten; four camps for IDPs; three bakeries and two centers for civil defense, in addition to more than a dozen of shells that targeted the Civil Defense volunteers during the evacuation of the injured and the victims. -

G Secto R Objective 1: Improve the Fo Od Security Status of Assessed Foo D Insecure Peo Ple by Emergency Humanita

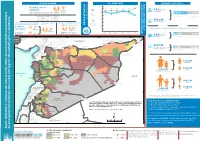

PEOPLE IN NEED PEOPLE IN NEED SO1 RESPONSE JANUARY 2017 CYCLE 8 7m Food & Livelihood 9 7 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m 6.3m million Assistance Million 5.01 ORIGIN Food Basket 6 Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) - 2017 SO1 6.16m 3.35 M 1.631.79 MM 5.96m 5.8m 5.89m 3.35m 1.63m Target 5.45m 5 From within Syria From neighbouring September 2015 8.7 Million 5.01m countries June 2016 9.4 Million WHOLE OF SYRIA 4 September 2016 9.0 Million 459,299 Cash and Voucher 3 LIFE SUSTAINING AND LIFE SAVING OVERALL TARGET JAN 2017 PLAN RESPONSE Reached FOOD ASSISTANCE (SO1) TARGET SO1 Food Basket, Cash & Voucher BENEFICIARIES Beneficiaries Food Basket, 2 Cash & Voucher - 7 Additionally, Bread - Flour and Ready to Eat Rations were also Provided 5.01 1 life sustaining MODALITIES AND Million 9 Million Million 0 Emergency 2 (72%) of SO1 Target AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC JAN BENEFICIARIES REACHED BY Response Million 291,911 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) - 2017 2.08million 1.79 M 36°0'0"E 38°0'0"E 40°0'0"E 42°0'0"E From within Syria From neighbouring Bread-Flour countries 7 Cizre- 1 g! 0 Kiziltepe-Ad Nusaybin-Al 2 T U R K E Y Darbasiyah Qamishli Peshkabour T U R K E Y g! g! g! Ayn al Arab Ceylanpinar-Ras Al Ayn Al Yaroubiya Islahiye Karkamis-Jarabulus g! - Rabiaa 635,144 g! g! Akcakale-Tall g! Bab As Abiad g! Emergency Response with 11,700 580,838 Salama Cobanbey g! Ready to Eat Ration From within Syria From neighbouring g! g! countries Reyhanli - A L --H A S A K E H Bab al Hawa g! N A L E P P O " A L E P P O 0 Karbeyaz ' 0 Yayladagi ° g! A R - R A Q Q A 6 g! A R - R A Q Q A 3 1,193,251 Women IID L E B L A T T A K IIA 1,374,537 2,567,787 Girls Female Beneciaries H A M A Mediterranean D E II R -- E Z -- Z O R Sea T A R T O U S II R A Q T A R T O U S Al Arida g! 1,081,796 Abu Men H O M S Kamal-Khutaylah H O M S g! 1,360,733 L E B A N O N 2,442,530 Boys N " Male Beneciaries 0 ' 0 ° 4 3 Masnaa-Jdeidet Yabous *Note: SADD is based on ratio of 49:51 for male/female due to lack of consistent data across UNDOF g! partners. -

Interventions by Sub-District (July 2019) Protection 1

Syria Protection Cluster (Turkey): Response Snapshot (as of 31 July 2019) Progress against Progress by Indicator 2019 HRP targets Interventions by Sub-District (July 2019) Turkey Hub 1.1.2 # of people reached through 3.1.1 # of communities/neighborhoods community-based protection services, that have at least one type of 98 including individual targeted assistance 261,986 specialized GBV services for persons with specific protection needs 1.2.1 # of people receiving legal 3.2.1 # women, men, girls and boys counselling or assistance, including 32,524 reached by GBV prevention and 235,785 civil documentation and HLP issues Legend Protection empowerment activities Gender Based Violence Not covered 500 501-1000 5.1.1 # of girls and boys engaging in 4.1.1 # of people who received risk 1001-5000 structured, sustained child 144,700 education from humanitarian 433,823 >5000 protection programmes, including Risk-Education actors psychosocial support 219,199 Interventions # of girls and boys who are # of people trained to conduct 8 Governorates 5.2.1 receiving specialized child 4.1.2 1,502 3,943 risk education 58 Organizations Child Protection protection services through case Mine Action management 57 Implementing partners Response In July 2019, 17 Protection Cluster members provided emergency response services for civilians recently displaced from Northern Hama and Southern Idleb due to the ongoing Interventions by Sub-Cluster (July 2019) hostilities. Cluster members provided 28,680 protection services to IDPs and affected host community members in 82 communities within 23 sub-districts in Idleb and Aleppo reaching 15,862 individuals (6005 girls, 6,115 boys, 2,687 women, and 1,055 men). -

Health Cluster Bulletin

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN April 2020 Fig.: Disinfection of an IDP camp as a preventive measure to ongoing COVID-19 Turkey Cross Border Pandemic Crisis (Source: UOSSM newsletter April 2020) Emergency type: complex emergency Reporting period: 01.04.2020 to30.04.2020 12 MILLION* 2.8 MILLION 3.7 MILLION 13**ATTACKS PEOPLE IN NEED OF HEALTH PIN IN SYRIAN REFUGGES AGAINST HEALTH CARE HEALTH ASSISTANCE NWS HNO 2020 IN TURKEY (**JAN - APR 2020) (A* figures are for the Whole of Syria HNO 2020 (All figures are for the Whole of Syria) HIGHLIGHTS • During April, 135,000 people who were displaced 129 HEALTH CLUSTER MEMBERS since December went back to areas in Idleb and 38 IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS REPORTING 1 western Aleppo governorates from which they MEDICINES DELIVERED TREATMENT COURSES FOR COMMON were displaced. This includes some 114,000 people 281,310 DISEASES who returned to their areas of origin and some FUNCTIONAL HEALTH FACILITIES HERAMS 21,000 IDPs who returned to their areas of origin, FUNCTIONING FIXED PRIMARY HEALTH forcing partners to re-establish health services in 141 CARE FACILITIES some cases with limited human resources. 59 FUNCTIONING HOSPITALS • World Health Day (7 April 2020) was the day to 72 MOBILE CLINICS celebrate the work of nurses and midwives and HEALTH SERVICES2 remind world leaders of the critical role they play 750,416 CONSULTATIONS in keeping the world healthy. Nurses and other DELIVERIES ASSISTED BY A SKILLED health workers are at the forefront of COVID-19 10,127 ATTENDANT response - providing high quality, respectful 8,530 REFERRALS treatment and care. Quite simply, without nurses, 822,930 MEDICAL PROCEDURES there would be no response. -

Cash Feasibility Assessment 2020

CASH FEASIBILITY ASSESSMENT 2020 North-West Syria This study was commissioned by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), conducted in collaboration with the Cash Working Group (CWG) for North-West Syria and funded by the European Commission Directorate General for Humanitarian Aid (ECHO). The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any of these organizations. The designations employed and the presentation of ma- terial throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of any organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergov- ernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operation- al challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. International Organization for Migration The UN Migration Agency - Syria Cross-Border Mission Gaziantep Office Güvenevler, 29115. Cd. No:1, 27560 Şehitkamil, Gaziantep, Turkey Tel: + 90 342 220 45 80 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.iomturkey.net Report content and design by Camille Strauss-Kahn Layout by Burak Cerci Cover Image: Use of an e-voucher card in a clothing shop in Azaz - courtesy of Syria Relief & IOM. © 2020 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. -

Losing Their Last Refuge: Inside Idlib's Humanitarian Nightmare

Losing Their Last Refuge INSIDE IDLIB’S HUMANITARIAN NIGHTMARE Sahar Atrache FIELD REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2019 Cover Photo: Displaced Syrians are pictured at a camp in Kafr Lusin near the border with Turkey in Idlib province in northwestern Syria. Photo Credit: AAREF WATAD/AFP/Getty Images. Contents 4 Summary and Recommendations 8 Background 9 THE LAST RESORT “Back to the Stone Age:” Living Conditions for Idlib’s IDPs Heightened Vulnerabilities Communal Tensions 17 THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE UNDER DURESS Operational Challenges Idlib’s Complex Context Ankara’s Mixed Role 26 Conclusion SUMMARY As President Bashar al-Assad and his allies retook a large swath of Syrian territory over the last few years, rebel-held Idlib province and its surroundings in northwest Syria became the refuge of last resort for nearly 3 million people. Now the Syrian regime, backed by Russia, has launched a brutal offensive to recapture this last opposition stronghold in what could prove to be one of the bloodiest chapters of the Syrian war. This attack had been forestalled in September 2018 by a deal reached in Sochi, Russia between Russia and Turkey. It stipulated the withdrawal of opposition armed groups, including Hay’at Tahrir as-Sham (HTS)—a former al-Qaeda affiliate—from a 12-mile demilitarized zone along the front lines, and the opening of two major HTS-controlled routes—the M4 and M5 highways that cross Idlib—to traffic and trade. In the event, HTS refused to withdraw and instead reasserted its dominance over much of the northwest. By late April 2019, the Sochi deal had collapsed in the face of the Syrian regime’s military escalation, supported by Russia.