Physiographic Features of Southeastern Ohio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpretation of Cumberland Escarpment and Highland Rim, South-Central Tennessee and Northeast Alabama

Interpretation of Cumberland Escarpment and Highland Rim, South-Central Tennessee and Northeast Alabama GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 524-C Interpretation of Cumberland Escarpment and Highland Rim, South-Central Tennessee and Northeast Alabama By JOHN T. HACK SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 524-C Theories of landscape origin are compared using as an example an area of gently dipping rocks that differ in their resistance to erosion UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1966 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Page Abstract___________________________________________ C1 Cumberland Plateau and Highland Rim as a system in Introduction_______________________________________ 1 equilibrium______________________________________ C7 General description of area___________________________ 1 Valleys and coves of the Cumberland Escarpment___ 7 Cumberland Plateau and Highland Rim as dissected and Surficial deposits of the Highland Rim____________ 10 deformed peneplains _____________________ ,... _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 4 Elk River profile_______________________________ 12 Objections to the peneplain theory____________________ 5 Paint Rock Creek profile________________________ 14 Eastern Highland Rim Plateau as a modern peneplain__ 6 Conclusions________________________________________ 14 Equilibrium concept -

When the Mountain Became the Escarpment.FH11

Looking back... with Alun Hughes WHEN THE MOUNTAIN BECAME THE ESCARPMENT The Niagara Escarpment hasnt always been But Coronelli was not the first to put Niagara known by that name. Early in the 19th century it on the map. That distinction belongs to Father Louis was often referred to as the Mountain, and of course Hennepin, the Recollect priest who was the first it is still called that in Hamilton and Grimsby today. European to describe Niagara Falls from personal We in eastern Niagara have largely forgotten the observation. In his Description de la Louisiane, name, though it survives in the City of Thorolds published in 1683, five years after his visit, he speaks motto Where the Ships Climb the Mountain. of le grand Sault de Niagara, and labels it thus on the accompanying map. This is the form that So when did the name Niagara Escarpment first prevails thereafter, and it is the spelling used for Fort come into use? And what about the areas other de Niagara, established by the French at the mouth Niagara names, like Niagara Falls, Niagara River of the river in 1726. The English followed suit, and Niagara Peninsula? When did these first appear? though on many early maps (e.g. Moll 1715, I dont pretend to have definitive answers there Mitchell 1782) they use the name Great Fall of are too many sources I have not seen but I can Niagara rather than Niagara Falls. suggest some preliminary conclusions. In his Description Hennepin also refers to la The name Niagara is definitely of native origin, belle Riviere de Niagara, so the name Niagara though there is no agreement about its meaning. -

The Abyssal Giant Pockmarks of the Black Bahama Escarpment: Relations Between Structures, fluids and Carbonate Physiography” by Thibault Cavailhes Et Al

Solid Earth Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/se-2020-11-RC2, 2020 SED © Author(s) 2020. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Interactive comment Interactive comment on “The abyssal giant pockmarks of the Black Bahama Escarpment: Relations between structures, fluids and carbonate physiography” by Thibault Cavailhes et al. Charles Paull (Referee) [email protected] Received and published: 10 April 2020 The manuscript describes a series of ∼circular depressions at the base of the Bahama Escarpment. These are curious features and their discovery may ultimately merit pub- lication. However, the manuscript more closely resembles a first draft, rather than a Printer-friendly version polished work. As is, the existing draft is too poorly written to fully follow many of the arguments in detail. Part of may be attributed to the challenge of writing in a second Discussion paper language. I have made some suggestions as to how to begin to sharpen the word- ing, but it is an incomplete effort. There are also a number of science related points C1 (also indicate below) that need to be considered before this could be recommended for publication. SED Why are these depressions called pockmarks from the outset? What is actually ob- served are approximately circular depressions. The term ‘pockmark’ has evolved to Interactive imply that the depression was somehow physically excavated by seepage, not phys- comment ical collapse. Moreover, it is not commonly been used in carbonate settings. The manuscript also refers to other similar depressions that have been previously been called plunge pools. This is yet another mechanism for surface erosion. -

1 a Film by Roger J. Kuhns What Was It Like in Door County Wisconsin 425 Million Years Ago? What

a film by Roger J. Kuhns www.rogerjameskuhns.com What was it like in Door County Wisconsin 425 million years ago? What has gone on in the geologic and biologic past beneath our feet? What are the changes we’re experiencing now? What might the future hold for our land, water, environment and communities? “Escarpment” is the natural history story of Eastern Wisconsin and the Niagara Escarpment region of the Great Lakes. The film was shot on location along the entire length of the Niagara Escarpment, with a Door County focus. It is a fast-paced fun voyage through billions of years of Eastern Wisconsin geologic and biologic past. The film reconstructs ecosystems that existed when the dolomitic rocks of the Niagara Escarpment were formed, considers if dinosaurs ever walked in what is now Door County, follows the path of glaciers, and many other major events in our rich geologic past. Locations around the world are featured to show what Eastern Wisconsin was like in the past. Animated sequences are used to illustrate parts of the story. The film helps to inform, enlighten, and guide us towards being better stewards of the land, and takes a glimpse of what a sustainable future might look like. In the spirit of Discovery Channel and National Geographic films, geologist and sustainologist Roger Kuhns produced this film for all ages. Kuhns has worked on the Niagara Escarpment and Great Lakes geology and ecology during the course of his career. FILM: Escarpment GENRE: Science / Nature / Travel PRODUCED BY: Roger J. Kuhns RUN TIME: 1 hour 33 minutes PRODUCTION: musicTOears Press CONTACT INFO: [email protected] / 860-910-8525 AVAILABLE AT: www.rogerjameskuhns.com MOVIE TRAILER: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YAyRp7VYFWs 1 2017-2018 Reviews from viewers of a film by Roger J. -

Historic Overview

Updated Reconnaissance Level Survey of Historic Resources Town of Amherst HISTORIC OVERVIEW LOCATION The Town of Amherst lies in northern Erie County, New York. It is bordered by Niagara County to the north, the Erie County towns of Clarence to the east, Cheektowaga to the south, and Tonawanda to the west. The total area of Amherst is approximately 53 square miles. ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING The natural environmental setting influenced prehistoric and historic settlement patterns in the Town of Amherst. The town lies within the Erie‐Ontario Lake Plain physiographic province, described as a nearly level lowland plain with few prominent topographic features. The area is underlain by Onondaga limestone dating to the Late Devonian period. Later glaciations shaped much of the western New York topography, including that of Amherst. One of the most prominent topographic features in the relatively featureless province is the Onondaga Escarpment, an east‐west trending hard limestone bedrock formation that lies in the southern portion of the Town of Amherst. The Onondaga Escarpment proved resistant to the effects of glacial scouring and it forms the southern boundary of a large basin once occupied by the shallow glacial Lake Tonawanda. Lake Tonawanda eventually receded leaving behind wetlands and deposits of clay and sand throughout much of northern Amherst (Owens et al. 1986:2). The most important drainages in the Town of Amherst are Tonawanda Creek, Ransom Creek, and Ellicott Creek. Tonawanda Creek forms the northern boundary between Amherst and Niagara County. It flows in a western direction and drains much of the eastern and Northern portions of Amherst. -

Beneficial Use Support Document Conotton Creek Basin 2016

Beneficial Use Support Document Conotton Creek Basin 2016 Conotton Creek at New Cumberland Road, RM 11.4 Division of Surface Water Ecological Assessment Section May 2021 Ohio EPA:DSW/EAS Conotton Creek Basin Use Support 2016 May 25, 2021 Introduction Ohio EPA conducted a comprehensive biological, habitat and water quality survey of the Conotton Creek watershed in 2016. While some limited sampling has previously been conducted on the Conotton Creek mainstem, most of the existing data date back to the 1980s. Few tributaries within the basin have ever been sampled by Ohio EPA prior to 2016. Most (22) of the 25 streams designated within the Ohio water quality standards are, therefore, not verified based on survey data. In addition, other tributaries within the basin remain undesignated. Figure 1 depicts the 2016 Conotton Creek basin study area and locations where sampling occurred, which included eleven locations arranged along the 43-mile long mainstem. Additional sampling occurred in twenty-five tributaries throughout the Conotton Creek watershed, which drains an area of 286 mi2 in Figure 1. The 2016 Conotton Creek Basin Study Area. Carroll, Harrison and Tuscarawas counties and which lies entirely within the Western Allegheny Plateau ecoregion in eastern Ohio. Conotton Creek is a major tributary of the Tuscarawas into which it discharges at river mile 65.5. Conotton Creek has been previously surveyed by Ohio EPA and it carries a verified warmwater habitat aquatic life use designation in the Ohio WQS that was validated by the 2016 survey once again. Most of the designated waterbodies in the Conotton Creek drainage basin are based on the original 1978 and 1985 state water quality standards. -

65Th Annual Tri-State Geological Field Conference 2-3 October 2004

65th Annual Tri-State Geological Field Conference 2-3 October 2004 Weis Earth Science Museum Menasha, Wisconsin The Lake & The Ledge Geological Links between the Niagara Escarpment and Lake Winnebago Joanne Kluessendorf & Donald G. Mikulic Organizers The Lake & The Ledge Geological Links between the Niagara Escarpment and Lake Winnebago 65th Annual Tri-State Geological Field Conference 2-3 October 2004 by Joanne Kluessendorf Weis Earth Science Museum, Menasha and Donald G. Mikulic Illinois State Geological Survey, Champaign With contributions by Bruce Brown, Wisconsin Geological & Natural History Survey, Stop 1 Tom Hooyer, Wisconsin Geological & Natural History Survey, Stops 2 & 5 William Mode, University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, Stops 2 & 5 Maureen Muldoon, University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, Stop 1 Weis Earth Science Museum University of Wisconsin-Fox Valley Menasha, Wisconsin WELCOME TO THE TH 65 ANNUAL TRI-STATE GEOLOGICAL FIELD CONFERENCE. The Tri-State Geological Field Conference was founded in 1933 as an informal geological field trip for professionals and students in Iowa, Illinois and Wisconsin. The first Tri-State examined the LaSalle Anticline in Illinois. Fifty-two geologists from the University of Chicago, University of Iowa, University of Illinois, Northwestern University, University of Wisconsin, Northern Illinois State Teachers College, Western Illinois Teachers College, and the Illinois State Geological Survey attended that trip (Anderson, 1980). The 1934 field conference was hosted by the University of Wisconsin and the 1935 by the University of Iowa, establishing the rotation between the three states. The 1947 Tri-State visited quarries at Hamilton Mound and High Cliff, two of the stops on this year’s field trip. -

Active Ohio Wetland Mitigation Banks 1/27/09

Active Ohio Mitigation Banks For the most up to date information visit: https://ribits.usace.army.mil/ribits_apex/f?p=107:2 LONG ARMY BANK NAME, SERVICE AREA TERM LOCATION CORPS SPONSOR MANAGER DISTRICT Big Darby-Hellbranch Upper Scioto River Columbus Prairie Twp., SW of Huntington -Stream + Wetlands (05060001) Metro Parks Columbus, Foundation Lower Scioto River Franklin County, Tributaries (05060002- Hellbranch Run 01/02/03/04) (0506001-22-01) Cherry Valley Grand River (04110004) Mt. Pleasant New Lyme Twp., S of Buffalo -Wetland Preservation, Ashtabula-Chagrin River Rod & Gun Sentinel, Ashtabula Ltd. (04110003) Club, County, Conneaut Creek Grand River Peters Creek-Mill Creek (04120101) Partners, Inc. (04110004-04-02) Grand River Lowlands Ashtabula-Chagrin River Mt. Pleasant Orwell Twp., W of Buffalo -Wetland Preservation, (04110003) Rod & Gun Orwell, Ltd. Grand River (04110004) Club, Ashtabula County, Cuyahoga River Grand River Mill Creek-Grand River (04110002) Partners, Inc. (0410004-03-03) Granger Black-Rocky River ODNR Granger Twp., Buffalo -Stream + Wetlands (04110001-01, 04110001- Division of Medina county, Foundation 02, 04110001-06) Wildlife North Branch West Cuyahoga River Branch Rocky River (04110002) within (04110001-01-02) Cuyahoga, Summit, Medina Counties Great Miami Upper Great Miami River Five Rivers Perry Twp., SW of Huntington (Trotwood) (05080001-14/18/19/20) Metro Parks Trotwood, Mitigation Bank Lower Great Miami River Montgomery County, -Five Rivers MetroParks (05080002-01/02/03/04/07) Headwaters Bear Creek (05080002-04-01) -

Floods of August and September 2004 in Eastern Ohio: FEMA Disaster Declaration 1556

Floods of August and September 2004 in Eastern Ohio: FEMA Disaster Declaration 1556 By Andrew D. Ebner, David E. Straub, and Jonathan D. Lageman In cooperation with the Ohio Emergency Management Agency Open-File Report 2008–1291 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Ebner, A.D., Straub, D.E., and Lageman, J.D., 2008, Floods of August and September 2004 in eastern Ohio— FEMA Disaster Declaration 1556: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2008–1291, 104 p. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................1 -

Late Cretaceous Stratigraphy of Black Mesa, Navajo and Hopi Indian Reservations, Arizona H

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/9 Late Cretaceous stratigraphy of Black Mesa, Navajo and Hopi Indian Reservations, Arizona H. G. Page and C. A. Repenning, 1958, pp. 115-122 in: Black Mesa Basin (Northeastern Arizona), Anderson, R. Y.; Harshbarger, J. W.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 9th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 205 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1958 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Flooding Along the Balcones Escarpment in Central Texas

FLOODING ALONG THE BALCONES ESCARPMENT, CENTRAL TEXAS S. Christopher Caran Victor R. Baker Bureau of Economic Geology Department of Geosciences The University of Texas at Austin University of Arizona Austin. TX 78713 Tucson. AZ 85721 A few days before the rains began to fall. a band of Tonkawa Indians that were camped in the river valley just below old Fort Griffin moved their camp to the top of one of the nearby hills. After the flood, on being asked why they moved to the top of the hill. the chief answered that when the snakes crawl towards the hills, the prairie do1s run towards the hills. and the grasshoppers hop towards the hills. it is time for the Indian to go to the hills. (Oral testimony attributed to an unnamed weather observer in Albany. Texas, following a memorable flood on the Clear Fork of the Brazos River in the late 1870's: recounted by Vance. 1934. p. 7.) ABSTRACT subbasins in Central Texas. Intense rainstorms over small watersheds throughoot the region have produced numerous High-magnitude floods occur with greater frequency in examples of discharge in excess of 100.000 cfs. Flooding the Balcones Escarpment area than in any other region of of this magnitude exacts a heavy toll from area residents the United States. Rates of precipitation and discharge per who incur the high cost of flood-control structures on trunk unit drainage area approach world maxima. The intensity streams (fig. 1). but also sustain casualties and damages of rainstorms is compounded by rapid runoff and limited associated with floods on small. -

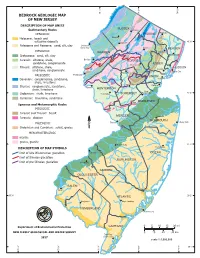

Bedrock Geologic Map of New Jersey

O O O 74 00’ BEDROCK GEOLOGIC MAP 75 00’ 74 30’ OF NEW JERSEY DESCRIPTION OF MAP UNITS SUSSEX Sedimentary Rocks Franklin CENOZOIC PASSAIC Mahwah Holocene: beach and Newton 41O 00’ estuarine deposits Andover Paleogene and Neogene: sand, silt, clay Delaware Water Gap Boonton BERGEN MESOZOIC WARREN Paterson Cretaceous: sand, silt, clay Hackensack Jurassic: siltstone, shale, Belvidere MORRIS sandstone, conglomerate ESSEX Morristown Triassic: siltstone, shale, HUDSON Newark sandstone, conglomerate Jersey City Gladstone Phillipsburg PALEOZOIC UNION Devonian: conglomerate, sandstone, Elizabeth shale, limestone Somerville Carteret Silurian: conglomerate, sandstone, Milford shale, limestone HUNTERDON New Brunswick 40O 30’ Ordovician: shale, limestone Flemington SOMERSET Cambrian: limestone, sandstone MIDDLESEX Igneous and Metamorphic Rocks MESOZOIC Jurassic and Triassic: basalt MERCER Jurassic: diabase Freehold MONMOUTH PALEOZOIC N Trenton Asbury Park Ordovician and Cambrian: schist, gneiss MESOPROTEROZOIC marble gneiss, granite O Mount Holly 40 00’ DESCRIPTION OF MAP SYMBOLS Toms River limit of late Wisconsinan glaciation Camden OCEAN limit of Illinoian glaciation BURLINGTON limit of pre-Illinoian glaciation Woodbury CAMDEN GLOUCESTER SALEM Salem O O 39 30’ ATLANTIC 39 30’ Bridgeton Mays Landing ICAL A OG ND L EO W CUMBERLAND G A T Y E E R Atlantic City S S R U E J R V E W E Y N 1835 0 5 10 15 20 mi Department of Environmental Protection CAPE MAY NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL AND WATER SURVEY 0 10 20 30 km Cape May 2017 Court House scale 1:1,000,000 39O 00’ O O O O O 76 00’ 75 30’ 75 00’ 74 30’ 74 00’ BEDROCK GEOLOGY OF NEW JERSEY For an area of its size, New Jersey has a uniquely diverse and interesting basalt and diabase are more resistant to erosion than the enclosing sandstone geology.