For the Past Five Years Pakistan Has Struggled to Navigate an Uneven Transition from Military to Civilian Rule While Confronting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan: Death Plot Against Human Rights Lawyer, Asma Jahangir

UA: 164/12 Index: ASA 33/008/2012 Pakistan Date: 7 June 2012 URGENT ACTION DEATH PLOT AGAINST HUMAN RIGHTS LAWYER Leading human rights lawyer and activist Asma Jahangir fears for her life, having just learned of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill her. Killings of human rights defenders have increased over the last year, many of which implicate Pakistan’s Inter- Service Intelligence agency (ISI). On 4 June, the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) alerted Amnesty International to information it had received of a plot by Pakistan’s security forces to kill HRCP founder and human rights lawyer Asma Jahangir. As Pakistan’s leading human rights defender, Asma Jahangir has been threatened many times before. However news of the plot to kill her is altogether different. The information available does not appear to have been intentionally circulated as means of intimidation, but leaked from within Pakistan’s security apparatus. Because of this, Asma Jahangir believes the information is highly credible and has therefore not moved from her home. Please write immediately in English, Urdu, or your own language, calling on the Pakistan authorities to: Immediately provide effective security to Asma Jahangir. Promptly conduct a full investigation into alleged plot to kill her, including all individuals and institutions suspected of being involved, including the Inter-Services Intelligence agency. Bring to justice all suspected perpetrators of attacks on human rights defenders, in trials that meet international fair trial standards and -

The Meeting Place. Radio Features in the Shina Language of Gilgit

Georg Buddruss and Almuth Degener The Meeting Place Radio Features in the Shina Language of Gilgit by Mohammad Amin Zia Text, interlinear Analysis and English Translation with a Glossary 2012 Harrassowitz Verlag · Wiesbaden ISSN 1432-6949 ISBN 978-3-447-06673-0 Contents Preface....................................................................................................................... VII bayáak 1: Giving Presents to Our Friends................................................................... 1 bayáak 2: Who Will Do the Job? ............................................................................... 47 bayáak 3: Wasting Time............................................................................................. 85 bayáak 4: Cleanliness................................................................................................. 117 bayáak 5: Sweet Water............................................................................................... 151 bayáak 6: Being Truly Human.................................................................................... 187 bayáak 7: International Year of Youth........................................................................ 225 References.................................................................................................................. 263 Glossary..................................................................................................................... 265 Preface Shina is an Indo-Aryan language of the Dardic group which is spoken in several -

Freedom Or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 4 Spring 2005 Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Hannibal Travis, Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq, 3 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 1 (2005). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol3/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2005 Northwestern University School of Law Volume 3 (Spring 2005) Northwestern University Journal of International Human Rights FREEDOM OR THEOCRACY?: CONSTITUTIONALISM IN AFGHANISTAN AND IRAQ By Hannibal Travis* “Afghans are victims of the games superpowers once played: their war was once our war, and collectively we bear responsibility.”1 “In the approved version of the [Afghan] constitution, Article 3 was amended to read, ‘In Afghanistan, no law can be contrary to the beliefs and provisions of the sacred religion of Islam.’ … This very significant clause basically gives the official and nonofficial religious leaders in Afghanistan sway over every action that they might deem contrary to their beliefs, which by extension and within the Afghan cultural context, could be regarded as -

By Syed Saleem Shahzad

Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) Brief Number 24 The Gathering Strength of Taliban and Tribal Militants in Pakistan Syed Saleem Shahzad 19th November 2007 About the Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) The Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) was established in the Department of Peace Studies at the University of Bradford, UK, in March 2007. It serves as an independent portal and neutral platform for interdisciplinary research on all aspects of Pakistani security, dealing with Pakistan's impact on regional and global security, internal security issues within Pakistan, and the interplay of the two. PSRU provides information about, and critical analysis of, Pakistani security with particular emphasis on extremism/terrorism, nuclear weapons issues, and the internal stability and cohesion of the state. PSRU is intended as a resource for anyone interested in the security of Pakistan and provides: • Briefing papers; • Reports; • Datasets; • Consultancy; • Academic, institutional and media links; • An open space for those working for positive change in Pakistan and for those currently without a voice. PSRU welcomes collaboration from individuals, groups and organisations, which share our broad objectives. Please contact us at [email protected] We welcome you to look at the website available through: http://spaces.brad.ac.uk:8080/display/ssispsru/Home Other PSRU Publications The following papers are amongst those freely available through the Pakistan Security Research Unit (PSRU) • Brief number 13. Pakistan – The Threat From Within • Brief number 14. Is the Crescent Waxing Eastwards? • Brief number 15. Is Pakistan a Failed State? • Brief number 16. Kashmir and The Process Of Conflict Resolution. • Brief number 17. -

ISI in Pakistan's Domestic Politics

ISI in Pakistan’s Domestic Politics: An Assessment Jyoti M. Pathania D WA LAN RFA OR RE F S E T Abstract R U T D The articleN showcases a larger-than-life image of Pakistan’s IntelligenceIE agencies Ehighlighting their role in the domestic politics of Pakistan,S C by understanding the Inter-Service Agencies (ISI), objectives and machinations as well as their domestic political role play. This is primarily carried out by subverting the political system through various means, with the larger aim of ensuring an unchallenged Army rule. In the present times, meddling, muddling and messing in, the domestic affairs of the Pakistani Government falls in their charter of duties, under the rubric of maintenance of national security. Its extra constitutional and extraordinary powers have undoubtedlyCLAWS made it the potent symbol of the ‘Deep State’. V IC ON TO ISI RY H V Introduction THROUG The incessant role of the Pakistan’s intelligence agencies, especially the Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI), in domestic politics is a well-known fact and it continues to increase day by day with regime after regime. An in- depth understanding of the subject entails studying the objectives and machinations, and their role play in the domestic politics. Dr. Jyoti M. Pathania is Senior Fellow at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. She is also the Chairman of CLAWS Outreach Programme. 154 CLAWS Journal l Winter 2020 ISI IN PAKISTAN’S DOMESTIC POLITICS ISI is the main branch of the Intelligence agencies, charged with coordinating intelligence among the -

E-Newsletter on COVID-19 Contents……

E-Newsletter on COVID-19 Vol. 02, No, 08 Issue: 23-25 January, 2021 …..About Newsletter Contents…… Subscribe In order to keep abreast of emerging issues at the National/International and Op-Eds local level, the SDPI brings Articles/Editorials/News comments …………………………….…...02 out a Bi-weekly E-Newsletter on “COVID-19”. National News It carries reference • Islamabad • Punjab information’s to the News • Khyber Pakhtunkhwa • Gilgit Baltistan items/Comments/Op-Eds • Sindh • AJK appearing in leading • Balochistan • National/International dailies. International News Newspapers Covered: • Countries News • Donors News • Dawn • The News SDPI Engagements • The Express Tribune • Webinars News • Researchers Articles • The Nation • Urdu Newspapers • SDPI: Other Engagement • Business Recorder coverages • Daily Times • Pakistan Observer • Pakistan Today • Urdu Point A Product of ASRC-SDPI Sustainable Development Policy Institute, SDPI Team: Data Managed by: 10-D West, 3rd Floor, Taimoor Chamber, Fazl-ul-Haq Road, Shahid Rasul , Abid Rasheed Blue Area, Islamabad. Pakistan, Compile & Layout Design by: Tel: +92.51. 2278134, Fax: 2278135, Ali Aamer Javed COVID _19: E-Newsletter Op-Eds/Articles/Editorials Op-Eds/Articles/Editorials Procuring vaccines Source: Editorial, The News, International , 2021-01-23 While countries in the neighbourhood, including India with its massive population, have begun dishing out the Covid- 19 vaccine to millions of people, with India setting particularly ambitious targets for itself and also providing vaccine to neighbouring countries including Bhutan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Seychelles, we get no images from Pakistan of people rolling up their sleeves t.....more >> The other have-nots Source: Zehra Waheed, Dawn, Islamabad , 2021-01-23 COVID-19 has impacted us all. -

Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

01-2180-2 CH 01:0545-1 10/13/11 10:47 AM Page 1 stephen p. cohen 1 Pakistan: Arrival and Departure How did Pakistan arrive at its present juncture? Pakistan was originally intended by its great leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, to transform the lives of British Indian Muslims by providing them a homeland sheltered from Hindu oppression. It did so for some, although they amounted to less than half of the Indian subcontinent’s total number of Muslims. The north Indian Muslim middle class that spearheaded the Pakistan movement found itself united with many Muslims who had been less than enthusiastic about forming Pak- istan, and some were hostile to the idea of an explicitly Islamic state. Pakistan was created on August 14, 1947, but in a decade self-styled field marshal Ayub Khan had replaced its shaky democratic political order with military-guided democracy, a market-oriented economy, and little effective investment in welfare or education. The Ayub experiment faltered, in part because of an unsuccessful war with India in 1965, and Ayub was replaced by another general, Yahya Khan, who could not manage the growing chaos. East Pakistan went into revolt, and with India’s assistance, the old Pakistan was bro- ken up with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. The second attempt to transform Pakistan was short-lived. It was led by the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who simultaneously tried to gain control over the military, diversify Pakistan’s foreign and security policy, build a nuclear weapon, and introduce an economic order based on both Islam and socialism. -

Prime Minister Muhammad Nawaz Sharif and Former President Asif

Prime Minister Muhammad Nawaz Sharif and former President Asif Ali Zardari jointly performed ground-breaking of the US 1.6 billion dollar Thar Coal Mining & Power Project of Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC)on Friday, 31st January, 2014 at Thar Coalfield Block-II near Islamkot. The project of Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company will initially provide 660 MW of power for Pakistan’s energy starved industrial units. It will complete in 2017 and help spur economic development and bring energy security to the country. The two leaders of PMLN and PPP performed the ground-breaking of the project that will be carried out by Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC) - a joint venture between Government of Sindh and Engro Corp. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, in his address said the launch of the project along with Asif Ali Zardari, had sent a message across that the political leadership should be united when it comes to the development of the country. He said this political trend must be set in Pakistan now and the leaders need to think about the country first regardless of their differences. He thanked former President Asif Zardari for inviting him to the ground-breaking of the Thar Coal project and said it was a matter of satisfaction that “we all are together and have the same priorities. Anyone who believes in the development of Pakistan, would be pleased that the country’s political leadership is together on this national event.” Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif termed the Thar Coal project a big national development project and suggested that the coal for all projects in Gaddani should be supplied from Thar. -

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Confrontationist Power Politics in Pakistan : JRSP, Vol

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Confrontationist Power Politics in Pakistan : JRSP, Vol. 58, No 2 (April-June 2021) Ulfat Zahra Javed Iqbal Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and the Beginning of Confrontationist Power Politics in Pakistan 1971-1977 Abstract: This paper mainly explores the genesis of power politics in Pakistan during 1971-1977. The era witnessed political disorders that the country had experienced after the tragic event of the separation of East Pakistan. Bhutto’s desire for absolute power and his efforts to introduce a system that would make him the main force in power alienated both, the opposition and his colleagues and supporters. Instead of a democratic stance on competitive policies, he adopted an authoritarian style and confronted the National People's Party, leading to an era characterized by power politics and personality clashes between the stalwarts of the time. This mutual distrust between Bhutto and the opposition - led to a coalition of diverse political groups in the opposition, forming alliances such as the United Democratic Front and the Pakistan National Alliance to counter Bhutto's attempts of establishing a sort of civilian dictatorship. This study attempts to highlight the main theoretical and political implications of power politics between the ruling PPP and the opposition parties which left behind deep imprints on the history of Pakistan leading to the imposition of martial law in 1977. If the political parties tackle the situation with harmony, a firm democracy can establish in Pakistan. Keywords: Pakhtun Students Federation, Dehi Mohafiz, Shahbaz (Newspaper), Federal Security Force. Introduction The loss of East Pakistan had caused great demoralization in the country. -

Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons

Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Paul K. Kerr Analyst in Nonproliferation Mary Beth Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation August 1, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34248 Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Summary Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal probably consists of approximately 110-130 nuclear warheads, although it could have more. Islamabad is producing fissile material, adding to related production facilities, and deploying additional nuclear weapons and new types of delivery vehicles. Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is widely regarded as designed to dissuade India from taking military action against Pakistan, but Islamabad’s expansion of its nuclear arsenal, development of new types of nuclear weapons, and adoption of a doctrine called “full spectrum deterrence” have led some observers to express concern about an increased risk of nuclear conflict between Pakistan and India, which also continues to expand its nuclear arsenal. Pakistan has in recent years taken a number of steps to increase international confidence in the security of its nuclear arsenal. Moreover, Pakistani and U.S. officials argue that, since the 2004 revelations about a procurement network run by former Pakistani nuclear official A.Q. Khan, Islamabad has taken a number of steps to improve its nuclear security and to prevent further proliferation of nuclear-related technologies and materials. A number of important initiatives, such as strengthened export control laws, improved personnel security, and international nuclear security cooperation programs, have improved Pakistan’s nuclear security. However, instability in Pakistan has called the extent and durability of these reforms into question. Some observers fear radical takeover of the Pakistani government or diversion of material or technology by personnel within Pakistan’s nuclear complex. -

Pakistan's Institutions

Pakistan’s Institutions: Pakistan’s Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Work They But How Can Matter, They Know We Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman and Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Essays by Madiha Afzal Ishrat Husain Waris Husain Adnan Q. Khan, Asim I. Khwaja, and Tiffany M. Simon Michael Kugelman Mehmood Mandviwalla Ahmed Bilal Mehboob Umar Saif Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain ©2018 The Wilson Center www.wilsoncenter.org This publication marks a collaborative effort between the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars’ Asia Program and the Fellowship Fund for Pakistan. www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program fffp.org.pk Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 Cover: Parliament House Islamic Republic of Pakistan, © danishkhan, iStock THE WILSON CENTER, chartered by Congress as the official memorial to President Woodrow Wilson, is the nation’s key nonpartisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue to inform actionable ideas for Congress, the Administration, and the broader policy community. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. -

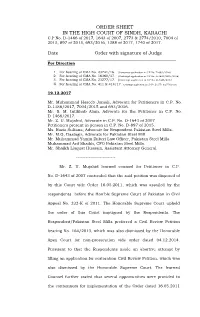

ORDER SHEET in the HIGH COURT of SINDH, KARACHI C.P No

ORDER SHEET IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH, KARACHI C.P No. D-1466 of 2017, 1643 of 2007, 2773 & 2774/2010, 7004 of 2015, 897 of 2015, 693/2016, 1388 of 2017, 1740 of 2017. _________________________________________________________ Date Order with signature of Judge ________________________________________________________ For Direction 1. For hearing of CMA No. 23741/16. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-693/2016) 2. For hearing of CMA No. 16360/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-1643/2007/2016) 3. For hearing of CMA No. 23277/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-1466/2017) 4. For hearing of CMA No. 411 & 414/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-2773 & 2774/2010) 19.12.2017 Mr. Muhammad Haseeb Jamali, Advocate for Petitioners in C.P. No. D-1388/2017, 7004/2015 and 693/2016. Mr. S. M. Intikhab Alam, Advocate for the Petitioner in C.P. No. D-1466/2017. Mr. Z. U. Mujahid, Advocate in C.P. No. D-1643 of 2007 Petitioners present in person in C.P. No. D-897 of 2015. Ms. Razia Sultana, Advocate for Respondent Pakistan Steel Mills. Mr. M.G, Dastagir, Advocate for Pakistan Steel Mill Mr. Muhammad Yamin Zuberi Law Officer, Pakistan Steel Mills. Muhammad Arif Shaikh, CFO Pakistan Steel Mills. Mr. Shaikh Liaquat Hussain, Assistant Attorney General. ------------------------- Mr. Z. U. Mujahid learned counsel for Petitioner in C.P. No. D-1643 of 2007 contended that the said petition was disposed of by this Court vide Order 16.05.2011, which was assailed by the respondents before the Hon’ble Supreme Court of Pakistan in Civil Appeal No.