An Ethics Primer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

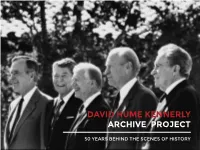

David Hume Kennerly Archive Creation Project

DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE CREATION PROJECT 50 YEARS BEHIND THE SCENES OF HISTORY The David Hume Kennerly Archive is an extraordinary collection of images, objects and recollections created and collected by a great American photographer, journalist, artist and historian documenting 50 years of United States and world history. The goal of the DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE CREATION PROJECT is to protect, organize and share its rare and historic objects – and to transform its half-century of images into a cutting-edge digital educational tool that is fully searchable and available to the public for research and artistic appreciation. 2 DAVID HUME KENNERLY Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist David Hume Kennerly has spent his career documenting the people and events that have defined the world. The last photographer hired by Life Magazine, he has also worked for Time, People, Newsweek, Paris Match, Der Spiegel, Politico, ABC, NBC, CNN and served as Chief White House Photographer for President Gerald R. Ford. Kennerly’s images convey a deep understanding of the forces shaping history and are a peerless repository of exclusive primary source records that will help educate future generations. His collection comprises a sweeping record of a half-century of history and culture – as if Margaret Bourke-White had continued her work through the present day. 3 HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE The David Hume Kennerly collection of photography, historic artifacts, letters and objects might be one of the largest and most historically significant private collections ever produced and collected by a single individual. Its 50-year span of images and objects tells the complete story of the baby boom generation. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

The Sponsor Effect: Breaking Through the Last Glass Ceiling

DEcember 2010 The Sponsor Effect: Breaking Through the Last Glass Ceiling By Sylvia Ann Hewlett, with Kerrie Peraino, Laura Sherbin, and Karen Sumberg Center for Work-Life Policy Survey research sponsored by: American Express, Deloitte, Intel, and Morgan Stanley RESEARCH REPORT The Sponsor Effect: Breaking Through the Last Glass Ceiling EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Women just aren’t making it to the very top. Despite making gains in middle and senior management, they hold just 3 percent of Fortune 500 CEO positions. In the C-suite, they’re outnumbered four to one. They account for less than 16 percent of all corporate officers, and comprise only 7.6 percent of Fortune 500 top earner positions. What’s keeping them under this last glass ceiling? What we uncover in this report is not a male conspiracy, but rather, a surprising absence of male (and female) advocacy. Women who are qualified to lead simply don’t have the powerful backing necessary to inspire, propel, and protect them through the perilous straits of upper management. Women lack, in a word, sponsorship. Spearheaded by American Express, Deloitte, Intel, and Morgan Stanley, the Hidden Brain Drain Task Force launched a study in the fall of 2009 to determine the nature and impact of sponsorship and examine just why women fail to either access or make better use of it.1 We found that the majority of ambitious women underestimate the pivotal role sponsorship plays in their advancement—not just within their current firm, but throughout their career and across their industry. More surprisingly, however, we found that women who do grasp the importance of relationship capital fail to cultivate it effectively. -

Spartan Daily 1.000 Parking Spaces

New garage prepare may not add Spartans S.U.'s musical week for homecoming any spaces by Morgan Hampton page 3 page 4 SJSU students won't gain a single parking space when the new $5.85 million parking garage is completed in 1982 if city urban renewal plans are finalized. The new garage has been approved by California State University and Colleges board of trustees, but still awaits master plan revision before plans are finalized. SJSU President Gail Fullerton said last week she expects no problem in getting approval at the next meeting in November. The 1.200 space garage will displace about 200 existing parking spaces at its site on Fourth Street between San Carlos and San Salvador streets, leaving a net gain of Spartan Daily 1.000 parking spaces. But 1,000 by SJSU students parking spaces now used Volume 73. Number 23 Serving San Jose State University since 1934 Friday. October 5, 1979 will be lost when the city reclaims its property on Fourth Street between San Fernando and San Carlos streets. The city plans to build condominiums, apartments and retail stores on the Fourth Street property, according to Pat Forst, coordinator for the San Jose Redevelopment Agency. When construction will begin is "touch and go," ac- cording to Forst, because the city is waiting for financial Hannah's removal unclear clearance of the developer's plans. Forst would not estimate when construction would begin, but she said even if urban renewal plans for the Ombudsman Fourth Street property are delayed until 1982, the city may have plans to use the lots for its own parking before position filled that time. -

Change Not Charity: Essays on Oxfam America's First 40 Years

Change not Charity: Essays on Oxfam America’s first 40 years Change not Charity: Essays on Oxfam America’s first 40 years Edited by Laura Roper Contents Acknowledgements 7 Author Bios 9 Introduction 15 The Early Years (1970-1977): Founding and Early Fruition 1. The Founding of Oxfam America, John W. Thomas 23 2. From Church Basement to the Board Room: Early Governance and Organizational Development, Robert C. Terry 28 3. Launching Oxfam’s Educational Mission, Nathan Gray 48 4. Humanitarian Response in Oxfam America’s Development: From Ambivalence to Full Commitment, Judith van Raalten and Laura Roper 57 5. Perspectives on Oxfam’s Partnership Model, Barbara Thomas-Slayter 74 The Short Years: Establishing an Institutional Identity and Ways of Working 6. Acting Strategically: Memories of Oxfam, 1977–1984, Joe Short 91 7. The Origins of Advocacy at Oxfam America, Laurence R. Simon 114 8. Humanitarian Aid Experiences at Home and Abroad: An Oxfam America Memoir, Michael Scott 140 9. Oxfam’s Cambodia Response and Effective Approaches to Humanitarian Action, Joel R. Charny 165 10. Women’s Empowerment in South Asia: Oxfam America’s First Gender Program, Martha Chen 175 11. Lessons from Lebanon, 1982–83, Dan Connell 186 The Hammock Years (1984–1995): Organizational Evolution in an Ever-Changing World 12. Walking the Talk: Development, Humanitarian Aid, and Organizational Development John Hammock 203 13. The 1984 Ethiopia Famine: A Turning Point for Oxfam America, Bernie Beaudreau 229 14. Finding My Feet: Reflections of a Program Officer on Her Work in Africa in the 1980s, Deborah Toler 236 15. Reflections on Working with Rebel Movements in the Horn of Africa, Rob Buchanan 251 16. -

Large Print Guide

Large Print Guide You can download this document from www.manchesterartgallery.org Sponsored by While principally a fashion magazine, Vogue has never been just that. Since its first issue in 1916, it has assumed a central role on the cultural stage with a history spanning the most inventive decades in fashion and taste, and in the arts and society. It has reflected events shaping the nation and Vogue 100: A Century of Style has been organised by the world, while setting the agenda for style and fashion. the National Portrait Gallery, London in collaboration with Tracing the work of era-defining photographers, models, British Vogue as part of the magazine’s centenary celebrations. writers and designers, this exhibition moves through time from the most recent versions of Vogue back to the beginning of it all... 24 June – 30 October Free entrance A free audio guide is available at: bit.ly/vogue100audio Entrance wall: The publication Vogue 100: A Century of Style and a selection ‘Mighty Aphrodite’ Kate Moss of Vogue inspired merchandise is available in the Gallery Shop by Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott, June 2012 on the ground floor. For Vogue’s Olympics issue, Versace’s body-sculpting superwoman suit demanded ‘an epic pose and a spotlight’. Archival C-type print Photography is not permitted in this exhibition Courtesy of Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott Introduction — 3 FILM ROOM THE FUTURE OF FASHION Alexa Chung Drawn from the following films: dir. Jim Demuth, September 2015 OUCH! THAT’S BIG Anna Ewers HEAT WAVE Damaris Goddrie and Frederikke Sofie dir. -

David Hume Kennerly Archive Project

DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE PROJECT 50 YEARS BEHIND THE SCENES OF HISTORY The David Hume Kennerly Archive is an extraordinary collection of images, objects and recollections created and collected by a great American photographer, journalist, artist and historian documenting 50 years of United States and world history. The goal of the DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE PROJECT is to protect, organize and share its rare and historic objects – and to transform its half-century of images into a cutting- edge digital educational tool that is fully searchable and available to the public for research and artistic appreciation. 2 DAVID HUME KENNERLY Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist David Hume Kennerly has spent his career documenting the people and events that have defined the world. The last photographer hired by Life Magazine, he has also worked for Time, People, Newsweek, Paris Match, Der Spiegel, Politico, ABC, NBC, CNN and served as Chief White House Photographer for President Gerald R. Ford. Kennerly’s images convey a deep understanding of the forces shaping history and are a peerless repository of exclusive primary source records that will help educate future generations. His collection comprises a sweeping record of a half-century of history and culture – as if Margaret Bourke-White had continued her work through the present day. 3 HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE The David Hume Kennerly collection of photography, historic artifacts, letters and objects might be one of the largest and most historically significant private collections ever produced and collected by a single individual. Its 50-year span of images and objects tells the complete story of the baby boom generation. -

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx. -

Lowell Public School Committee Special Meeting Agenda

Lowell Public School Committee Special Meeting Agenda Date: August 11, 2021 Time: 6:30PM Location: City Council Chamber, 375 Merrimack Street, 2nd Floor, Lowell, MA 01852 1. SALUTE TO FLAG 2. ROLL CALL 3. MINUTES 3.1. Approval Of The Minutes Of The Special Meeting Of The Lowell School Committee Of Tuesday, July 20, 2021 Documents: LSC SPECIAL MEETING MINUTES - JULY 20, 2021.PDF 3.2. Approval Of The Minutes Of The Regularly Scheduled Lowell School Committee Meeting Of Wednesday, July 21, 2021 Documents: LSC MINUTES - JULY 21, 2021.PDF 4. PERMISSION TO ENTER 4.1. Permission To Enter: August 11, 2020 Documents: PERMISSION TO ENTER -AUGUST 11, 2021.PDF PERMISSION TO ENTER -AUGUST 11, 2021 II.PDF 5. MOTIONS 5.1. [By Connie Martin]: Request that the existing Climate Specialist position job description be updated to reflect the School Committee's vote to include a requirement of Social Worker licensure 5.2. [By Jackie Doherty]: Request the Superintendent present the finalists for the Special Education Director position to the school committee. 5.3. [By Jackie Doherty]: Request the Superintendent confirm that all Chiefs are licensed and have the appropriate educator certifications required by the state. 6. REPORTS OF THE SUPERINTENDENT 6.1. Building Readiness And School Opening Update Documents: SCHOOL RE-OPENING UPDATE.PDF 6.2. Enrollment Report Documents: 8.6.21 ENROLLMENT REPORT.PDF 7. NEW BUSINESS 7.1. First Reading Of 2021-2022 COVID-19 Safety Protocol Policy Documents: SAFETY PROTOCOL DRAFT POLICY.PDF FALL IN-PERSON LEARNING .PDF MEMO- MASK POLICY- NEW DOCUMENTS AVAILABLE.PDF LETTER FROM MRS. -

NOMINEES for the 40Th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY

NOMINEES FOR THE 40th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED NBC’s Andrea Mitchell to be honored with Lifetime Achievement Award September 24th Award Presentation at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in NYC New York, N.Y. – July 25, 2019 (revised 8.19.19) – Nominations for the 40th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Tuesday, September 24th, 2019, at a ceremony at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. “The clear, transparent, and factual reporting provided by these journalists and documentarians is paramount to keeping our nation and its citizens informed,” said Adam Sharp, President & CEO, NATAS. “Even while under attack, truth and the hard-fought pursuit of it must remain cherished, honored, and defended. These talented nominees represent true excellence in this mission and in our industry." In addition to celebrating this year’s nominees in forty-nine categories, the National Academy is proud to honor Andrea Mitchell, NBC News’ chief foreign affairs correspondent and host of MSNBC's “Andrea Mitchell Reports," with the Academy’s Lifetime Achievement Award for her groundbreaking 50-year career covering domestic and international affairs. The 40th Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards honors programming distributed during the calendar -

Chinese Investment in Israeli Technology and Infrastructure

C O R P O R A T I O N SHIRA EFRON, KAREN SCHWINDT, EMILY HASKEL Chinese Investment in Israeli Technology and Infrastructure Security Implications for Israel and the United States For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR3176 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0435-0 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2020 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover design: Rick Penn-Kraus Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Relations between China and Israel have expanded rapidly since the early 2000s in numerous areas, including diplomacy, trade, invest- ment, construction, educational partnerships, scientific cooperation, and tourism. -

NOMINEES for the 39Th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS

NOMINEES FOR THE 39th ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED Paula S. Aspell of PBS’ NOVA to be honored with Lifetime Achievement Award October 1st Award Presentation at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall in NYC New York, N.Y. – July 26, 2018 – Nominations for the 39th Annual News and Documentary Emmy® Awards were announced today by The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy Awards will be presented on Monday, October 1st, 2018, at a ceremony at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall in the Time Warner Complex at Columbus Circle in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. “New technologies are opening up endless new doors to knowledge, instantly delivering news and information across myriad platforms,” said Adam Sharp, interim President& CEO, NATAS. “With this trend comes the immense potential to inform and enlighten, but also to manipulate and distort. Today we honor the talented professionals who through their work and creativity defend the highest standards of broadcast journalism and documentary television, proudly providing the clarity and insight each of us needs to be an informed world citizen.” In addition to celebrating this year’s nominees in forty-nine categories, the National Academy is proud to be honoring Paula S. Apsell, Senior Executive Director of PBS’ NOVA, at the 39th News & Documentary Emmy Awards with the Lifetime Achievement Award for her many years of science broadcasting excellence. The 39th Annual News & Documentary Emmy® Awards honors programming distributed during the calendar year 2017.