Copyright 2015 Mina Sohaj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

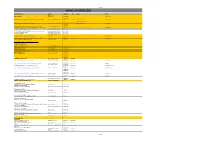

Grad Zagreb (01)

ADRESARI GRAD ZAGREB (01) NAZIV INSTITUCIJE ADRESA TELEFON FAX E-MAIL WWW Trg S. Radića 1 POGLAVARSTVO 10 000 Zagreb 01 611 1111 www.zagreb.hr 01 610 1111 GRADSKI URED ZA STRATEGIJSKO PLANIRANJE I RAZVOJ GRADA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/II 01 610 1575 610-1292 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr [email protected] 01 658 5555 01 658 5609 GRADSKI URED ZA POLJOPRIVREDU I ŠUMARSTVO Zagreb, Avenija Dubrovnik 12/IV 01 658 5600 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 01 610 1111 01 610 1169 GRADSKI URED ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE, ZAŠTITU OKOLIŠA, Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 610 1168 IZGRADNJU GRADA, GRADITELJSTVO, KOMUNALNE POSLOVE I PROMET 01 610 1560 01 610 1173 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 1.ODJEL KOMUNALNOG REDARSTVA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 06 111 2.DEŽURNI KOMUNALNI REDAR (svaki dan i vikendom od 08,00-20,00 sati) Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 566 3. ODJEL ZA UREĐENJE GRADA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 184 4. ODJEL ZA PROMET Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 61 01 111 Zagreb, Ulica Republike Austrije 01 610 1850 GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA PROSTORNO UREĐENJE 18/prizemlje 01 610 1840 01 610 1881 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr 01 485 1444 GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA ZAŠTITU SPOMENIKA KULTURE I PRIRODE Zagreb, Kuševićeva 2/II 01 610 1970 01 610 1896 [email protected] www.zagreb.hr GRADSKI ZAVOD ZA JAVNO ZDRAVSTVO Zagreb, Mirogojska 16 01 469 6111 INSPEKCIJSKE SLUŽBE-PODRUČNE JEDINICE ZAGREB: 1)GRAĐEVINSKA INSPEKCIJA 2)URBANISTIČKA INSPEKCIJA 3)VODOPRAVNA INSPEKCIJA 4)INSPEKCIJA ZAŠTITE OKOLIŠA Zagreb, Trg Stjepana Radića 1/I 01 610 1111 SANITARNA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Šubićeva 38 01 658 5333 ŠUMARSKA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Zapoljska 1 01 610 0235 RUDARSKA INSPEKCIJA Zagreb, Ul Grada Vukovara 78 01 610 0223 VETERINARSKO HIGIJENSKI SERVIS Zagreb, Heinzelova 6 01 244 1363 HRVATSKE ŠUME UPRAVA ŠUMA ZAGREB Zagreb, Kosirnikova 37b 01 376 8548 01 6503 111 01 6503 154 01 6503 152 01 6503 153 01 ZAGREBAČKI HOLDING d.o.o. -

ACP Cultural Component of Citizenship

the CULTURAL COMPONENT of CITIZENSHIP an inventory of challenges The European House for Culture on behalf of the Access to Culture Platform has been funded with the support from the European Commission. This communication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. The Access to Culture Platform is hosted at the European House for Culture. 1 the cultural component of citizenship : an inventory of challenges Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 5 The Cultural Component of Citizenship: an Inventory of Challenges ............... 6 Steve Austen European Citizenship and the Role of Art and Culture .................................. 10 Mary Ann DeVlieg Citizenship and Culture .................................................................................. 28 DEFINING THE CULTURAL COMPONENT OF CITIZENSHIP 37 Mathieu Kroon Gutiérrez Europe and the Challenge of Virtuous Citizenship. What is the Role of Culture? ....................................................................................................................... 38 HOW IS CULTURAL CITIZENSHIP PRACTICED? 53 Matina Magkou Geographies of Artistic Mobility for the Formation and Confirmation of European Cultural Citizenship. ...................................................................... 54 Natalia Grincheva “Canada’s Got Treasures” Constructing National Identity through Cultural Participation ................................................................................................. -

APPENDIX Lesson 1.: Introduction

APPENDIX Lesson 1.: Introduction The Academy Awards, informally known as The Oscars, are a set of awards given annually for excellence of cinematic achievements. The Oscar statuette is officially named the Academy Award of Merit and is one of nine types of Academy Awards. Organized and overseen by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS),http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academy_Award - cite_note-1 the awards are given each year at a formal ceremony. The AMPAS was originally conceived by Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer studio executive Louis B. Mayer as a professional honorary organization to help improve the film industry’s image and help mediate labor disputes. The awards themselves were later initiated by the Academy as awards "of merit for distinctive achievement" in the industry. The awards were first given in 1929 at a ceremony created for the awards, at the Hotel Roosevelt in Hollywood. Over the years that the award has been given, the categories presented have changed; currently Oscars are given in more than a dozen categories, and include films of various types. As one of the most prominent award ceremonies in the world, the Academy Awards ceremony is televised live in more than 100 countries annually. It is also the oldest award ceremony in the media; its equivalents, the Grammy Awards (for music), the Emmy Awards (for television), and the Tony Awards (for theater), are modeled after the Academy Awards. The 85th Academy Awards were held on February 24, 2013 at the Dolby Theatre in Los Angeles, California. Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academy_Award Time of downloading: 10th January, 2013. -

Bitef Satnica Preuzmite

SREDA / WEDNESDAY 20.09. Kulturni centar Beograda, Bitef biblioteka / Promocija knjige NOĆNI DNEVNIK, 1985 – 1991 / Galerija Artget / 20:00 Bitef Library Book promotion NIGHT DIARY 1985 – 1991 Belgrade Cultural Centre, Artget Gallery ČETVRTAK / THURSDAY 21.09. Radionica / Radionica pozorišne kritike SUMNJIVA LICA / Festivalski centar / 12:00 Workshop Theatre criticism workshop PERSONS OF INTERESTS Festival Centre PETAK / FRIDAY 22.09. Promocija knjige KULTURNA DIPLOMATIJA: Bitef biblioteka / UMETNOST, FESTIVALI I GEOPOLITIKA / Festivalski centar / 16:00 Bitef Library Book promotion CULTURAL DIPLOMACY: Festival Centre ARTS, FESTIVALS AND GEOPOLITICS Glavni program / Klub Bitef teatra / 18:00 Main Programme QUIZOOLA! Bitef Theatre Club SUBOTA / SATURDAY 23.09. 24/7: DUGE PREDSTAVE I NIKAD KRAJA / Svečana sala Rektorata Međunarodna tribina / Univerziteta umetnosti / 24/7: DURATIONAL PERFORMANCES 10:30 International panel discussion Formal Hall, University of Arts, WITH NO END IN SIGHT The Rectory OLIMP Glavni program / U SLAVU KULTA TRAGEDIJE – PREDSTAVA OD 24 SATA / Sava Centar / 18:00 Main Programme MOUNT OLYMPUS Sava Centre TO GLORIFY THE CULT OF TRAGEDY – A 24H PERFORMANCE PONEDELJAK / MONDAY 25.09. Otvaranje i interaktivna prezentacija Bitef polifonija / TROGLASNE INVENCIJE BITEF POLIFONIJE / Ustanova kulture „Parobrod“ / 12:00 Bitef Polyphony Opening and interactive presentation Cultural Institution “Parobrod” THREE-PART INVENTIONS OF BITEF POLYPHONY Centar za kulturnu Bitef polifonija / Predstava MALA ŽURKA PROPUŠTENOG PLESA / dekontaminaciju -

Programme Case Petrovaradin Small

INTERNATIONAL SUMMER ACADEMY PROGRAMME GUIDE Credits Contents Project organizers Europa Nostra Faculty of sport and Institute for the Welcome note 3 Serbia tourism TIMS protection of cultural monuments Programme overview 4 Partners Detailed programme 5 Public events 9 Practical info 11 Edinburgh World Global observatory on the Europa Nostra Lecturers 12 Heritage historic urban landscape Participants 15 Support Researchers 23 Host team 25 Radio 021 Project funders Foundation NS2021 European Capital of Culture 2 Welcome note Dear Participants, of Petrovaradin Fortress, learn from it and reimagine its future development. We are excited to present you the programme guide and welcome you to the Summer Academy on In this programme guide, we wanted to offer you plenty Managing Historic Urban Landscapes! The Academy is of useful information to get you ready for the upcoming happening at the very important time for the fortress week of the Summer Academy. In the following pages, and the city as a whole. Being awarded both a Youth you can find detailled programme of the week, some and Cultural capital of Europe, Novi Sad is going practical information for your arrival to Petrovaradin through many transformations. Some of these fortress with a map of key locations, and short transformations, including the ones related to the biographies of all the people that will share the same Petrovaradin Fortress, are more structured and place, as well as their knowledge and perspectives thoroughly planned then others. Still, we believe that in during this joint adventure: lecturers, facilitators, Višnja Kisić all of these processes knowledge, experience and participants, researchers and volunteers. -

PUBLIC THEATRE's SOCIAL ROLE and ITS Audiencea

ТEME, г. XLV, бр. 1, јануар − март 2021, стр. 213−229 Оригинални научни рад https://doi.org/10.22190/TEME190702012M Примљено: 2. 7. 2019. UDK 792: 316.4.062 Ревидирана верзија: 17. 11. 2021. Одобрено за штампу: 26. 2. 2021. PUBLIC THEATRE’S SOCIAL ROLE AND ITS AUDIENCEa Ksenija Marković Božović* University of Arts in Belgrade, Faculty of Dramatic Arts, Belgrade, Serbia Abstract Today, public theatre is directed toward adapting to its contemporary socio- economic context. In doing this, it is trying to preserve its artistic values and at the same time fulfill and diversify its social functions and missions. When we talk about public theatre’s social function, i.e. the public value it produces, some of the main issues concern its contribution to the most pressing social matters. In general, these issues concern public theatre’s role in strengthening social cohesion, cultural emancipation and social inclusion, its role in the process of opening dialogues, revising formal history and re-examining traditional forms of thinking. Fulfilment of these functions is strongly linked with the character of public theatre’s audiences. In more practical terms, the scope of public theatre’s social influence is dependent on how homogenous its audiences are. If one considers artistic organizations’ need for sustainability as a key factor in their need for constantly widening their audience, and particularly the inclusion of “others” (those not belonging to the dominant cultural group), in the context of contemporary society’s need for social and cultural inclusion, then the task of today’s public theatres becomes rather difficult. Simply said, there are too many needs to be met at the same time. -

Havc-Izvjestaj-O-Radu-2013.Pdf

Izvjeπtaj o radu 20131 2 Izvjeπtaj 2013 o radu 1 Sadržaj 0. Uvodnik 5 2.3. Distribucija i prikazivanje kratkometražnog filma 20 2.4. Ostale vijesti vezane uz distribuciju 21 1. Filmska proizvodnja u 2013. godini 6 2.5. Međunarodna distribucija 21 A) Dugometražni igrani film 8 1.1. Prikazani filmovi 8 3. Hrvatski filmovi na svjetskim festivalima 22 1.2. Prikazane manjinske koprodukcije 8 3.1. Hrvatski filmovi na festivalima prve kategorije 24 1.3. Filmovi u postprodukciji 9 3.2. Hrvatski filmovi na ostalim festivalima 25 1.4. Snima se / snimat će se... 9 B) Dugometražni dokumentarni film 10 4. Međunarodna promocija 26 1.5. Završeni naslovi i manjinske koprodukcije 10 4.1. Promocija i plasman na međunarodnim 28 1.6. Filmovi u produkciji i postprodukciji 10 filmskim sajmovima i festivalima C) Kratkometražni animirani, dokumentarni, 11 4.2. Programi hrvatskog filma u inozemstvu 29 eksperimentalni i igrani film 4.3. Programi stručnog usavršavanja hrvatskih filmskih 30 1.7. Završeni i prikazani filmovi 11 profesionalaca 1.8. Filmovi u produkciji i postprodukciji 11 4.4. Javni poziv za međunarodnu suradnju 33 1.9. Dugometražni animirani i eksperimentalni film 11 4.5. Promocija hrvatskih kandidata za nagradu Oscar 35 D) Potpore u 2013. godini 12 i Europsku filmsku nagradu E) Jedna slika iz Domovinskog rata 15 5. Digitalizacija nezavisnih kinoprikazivača 36 2. Distribucija i gledanost 16 5.1. Javna nabava 39 2.1. Razdoblje 2012. /2013. 18 5.2. Ugovorne obveze i potpisivanje ugovora 40 2.2. Druga polovica 2013. godine 18 5.3. Digitalno opremanje dvorana i otvaranje kina 40 5.4. -

Jewish Communities in the Political and Legal Systems of Post-Yugoslav Countries

TRAMES, 2017, 21(71/66), 3, 251–271 JEWISH COMMUNITIES IN THE POLITICAL AND LEGAL SYSTEMS OF POST-YUGOSLAV COUNTRIES Boris Vukićević University of Montenegro Abstract. After the dissolution of Yugoslavia, the Jewish community within Yugoslavia was also split up, and now various Jewish communities exist in the seven post-Yugoslav countries. Although all of these communities are relatively small, their size, influence, and activity vary. The political and legal status of Jewish communities, normatively speaking, differs across the former Yugoslav republics. Sometimes Jews or Jewish communities are mentioned in constitutions, signed agreements with governments, or are recognized in laws that regulate religious communities. Despite normative differences, they share most of the same problems – a slow process of return of property, diminishing numbers due to emigra- tion and assimilation, and, although on a much lower scale than in many other countries, creeping anti-Semitism. They also share the same opportunities – a push for more minority rights as part of ‘Europeanization’ and the perception of Jewish communities as a link to influential investors and politicians from the Jewish diaspora and Israel. Keywords: Jewish communities, minority rights, post-communism, former Yugoslavia DOI: https://doi.org/10.3176/tr.2017.3.04 1. Introduction In 1948, the first postwar census in Yugoslavia counted 6,538 people of Jewish nationality, although many Jews identified as other nationalities (e.g. Croat, Serb) in the census while identifying religiously as Jewish, as seen by the fact that Jewish municipalities (or communities) across Yugoslavia had 11,934 members (Boeckh 2006:427). The number of Jews in Yugoslavia decreased in the following years after the foundation of the State of Israel. -

1 Lenki I Relji, Mojim Unucima

Lenki i Relji, mojim unucima 1 2 Feliks Pašić MUCI Ljubomir Draškić ili živeti u pozorištu 3 4 Ulaz u vilu »Nada« u Omišlju na ostrvu Krku 5 6 Mladom Svetozaru Cvetkoviću, tek pristiglom u Atelje 212, činio se kao ka- kav veliki lutan, očiju dubokih i crnih, sa podočnjacima koji su s godinama posta- jali sve tamniji i dublji. Mira Stupica pamti jedno štrkljasto i visoko dete, krakato, okato, nosato i pomalo dremljivo, koje je kapke imalo uvek napola spuštene, kao roletne. I u sećanju Aleksandra–Luja Todorovića javlja se u istoj slici: visok, štrkljast, šiljat, neopisivo mršav. Vojislavu Kostiću je, tako visok i mršav, sa šišanom bradom, ličio na Don Kihota. Ivana Dimić je imala dvanaest godina kad ga je prvi put videla, na slavi na koju je došla s roditeljima. Među gostima se izdvajao visok, mršav, duhovit čovek koji je psovao. Ogroman, tamnog lica i brade, izgledao joj je kao neki Azijat. Aleksandar–Saša Gruden seća ga se kao klinca koji je s majkom došao kod očeve rodbine u Užice. Prilog opštem utisku: štkljast, nosat, s ogromnim kolenima. Kad su ga upitali kako je, odgovorio je: »Zaštopal mi se nosek.« Posle je objašnjavao da je imao jezički problem: »Govorio sam hrvatski.« Dolasku u Užice 1941. godine prethodi prva velika životna avantura. Od ranih dana naučio je da svet i ljude vidi u slikama. U slikama Zadra, u koji se porodica 1939. seli iz Zagreba, kada je otac Sreten postavljen za vicekonzula Kraljevskog konzulata, prelamaju se, između ostalih, prizori ogromnog stana u kome, po jednom dugačkom hodniku, vozi bicikl. -

FILM FESTIVAL 22Nd - 29Th November 2012

UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE EMBASSY OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA IN PRETORIA SERBIAN ARTS AND CULTURE SOCIETY AFRICA SERBIAN FILM FESTIVAL 22nd - 29th November 2012 NU METRO, MONTECASINO An author’s perspective of the world Film, as a sublimation of all arts, is a true medium, a universal vehicle with which the broader public is presented with a world view, as seen by the eye of the fi lmmaker. Nowadays, due to the global economic crisis, which is ironically producing technological and all sorts of other develop- ments, an increasing number of people are pushed to the margins of average standards of living, and fi lmmakers are given the chance to bring under their ‘protection’ millions of disillusioned people with their fi lmmaking capabilities. Art, throughout its history, has always praised but has also been heavily critical of its subject. Film is not just that. Film is that and so much more. Film is life itself and beyond life. Film is everything many of us dream about but never dare to say out loud. That is why people love fi lms. That is why it is eternal. It tears down boundaries and brings together cul- tures. It awakens curiosity and builds bridges from one far away coast to another. Film is a ‘great lie’ but an even greater truth. Yugoslavian, and today the Serbian fi lm industry has always been ‘in trend’. It might sound harsh but, unfortunately, this region has always provided ample ‘material’ for fi lms. Under our Balkan clouds there has been an ongoing battle about which people are older, which came and settled fi rst, who started it and who will be fi rst to leave and such battles have been and continue to be an inspiration to fi lm producers. -

Jubilarni De~Iji Fudbalski Festival

Jubilarni de~iji fudbalski festival 2014 20-23 June 2014 1 2 Dobrodo{li na Welcome to Carnex kup 2014 Carnex cup 2014 Po{tovani fudbalski timovi, {kole i akademije fudbala, To all football clubs, schools and football academies, it is veliko nam je zadovoljstvo da Vas pozovemo na tre}i our great pleasure to invite you to the third "Carnex cup" "Carnex kup" me|unarodno takmi~enje najmla|ih international competition for our youngest football players. fudbalera. We hope you will be interested in taking part in this sports Nadamo se da }ete biti zainteresovani da u~estvujete na and cultural event, which will be held in Novi Sad, Serbia, ovom sportskom i kulturnom doga|aju, koji se odr`ava from the 19th to the 22th of June, 2014. u Novom Sadu u Srbiji, od 19.06. do 22.06.2014. godine Our main partners at this event are the City of Novi Sad, Glavni partneri u organizaciji takmi~enja su Football Association of Serbia, Carnex. nam Grad Novi Sad, FS Srbije, Carnex. We expect that a large number of teams from all O~ekujemo veliki broj ekipa iz cele across Europe will be in attendance. We would Evrope. @elimo svima da omogu}imo like to provide everyone, especially the children dru`enje, ostvarivanje novih poznanstava from different countries, with the opportunity to i prijateljstava, posebno deci iz raznih create new friendships and to participate in a zemalja, da u~estvuju na turniru najvi{eg tournament of the highest standard. standarda. Dragi prijatelji, Pozivamo Vas da dođete u Srbiju u Novi Sad i učestvujete na „Carnex kup”-u. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Cinematic Representations of Nationalist-Religious Ideology in Serbian Films during the 1990s Milja Radovic Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh March 2009 THESIS DECLARATION FORM This thesis is being submitted for the degree of PhD, at the University of Edinburgh. I hereby certify that this PhD thesis is my own work and I am responsible for its contents. I confirm that this work has not previously been submitted for any other degree. This thesis is the result of my own independent research, except where stated. Other sources used are properly acknowledged. Milja Radovic March 2009, Edinburgh Abstract of the Thesis This thesis is a critical exploration of Serbian film during the 1990s and its potential to provide a critique of the regime of Slobodan Milosevic.