Citigroup: a Case Study in Managerial and Regulatory Failures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Pdf 707.34 KB

NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION IN OR INTO OR TO ANY PERSON LOCATED OR RESIDENT IN THE UNITED STATES, ITS TERRITORIES AND POSSESSIONS, ANY STATE OF THE UNITED STATES OR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA (INCLUDING PUERTO RICO, THE U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS, GUAM, AMERICAN SAMOA, WAKE ISLAND AND THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS) OR IN OR INTO OR TO ANY PERSON LOCATED OR RESIDENT IN ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DISTRIBUTE THIS DOCUMENT. EXOR N.V. ANNOUNCES FINAL RESULTS OF ITS TENDER OFFERS Amsterdam, 20 January 2021. EXOR N.V. (the Company) hereby announces the final results of its invitations to eligible Noteholders of its €750,000,000 2.125 per cent. Notes due 2 December 2022, ISIN XS1329671132 (of which €750,000,000 is currently outstanding) (the 2022 Notes) and its €650,000,000 2.50 per cent. Notes due 8 October 2024, ISIN XS1119021357 (of which €650,000,000 is currently outstanding) (the 2024 Notes, and together with the 2022 Notes, the Notes and each a Series) to tender their Notes for purchase by the Company for cash up to an aggregate maximum acceptance amount of €400,000,000 in aggregate nominal amount (the Maximum Acceptance Amount) (such invitations, the Offers and each an Offer). The Offers were announced on 12 January 2021 and were made on the terms and subject to the conditions set out in the tender offer memorandum dated 12 January 2021 (the Tender Offer Memorandum) prepared in connection with the Offers, and subject to the offer and distribution restrictions set out in the Tender Offer Memorandum. -

From the American Dream to … Bailout America: How the Government

From the American dream to … bailout America: How the government loosened credit standards and led to the mortgage meltdown Compiled by Edward Pinto, American Enterprise Institute In the early 1990s, Fannie Mae‘s CEO Jim Johnson developed a plan to protect Fannie‘s lucrative charter privileges bestowed by Congress. Ply Congress with copious amounts of affordable housing and Fannie‘s privileges would be secure. It required ―transforming the housing finance system‖ by drastically loosening of loan underwriting standards. Fannie garnered support from community advocacy groups like ACORN and members of Congress. In 1995 President Clinton formalized Fannie‘s plan into the National Homeownership Strategy. President Clinton stated it ―will not cost the taxpayers one extra cent.‖ From 1992 onward, ―skin in the game‖ was progressively eliminated from housing finance. And it worked – Fannie‘s supporters in and outside Congress successfully protected Fannie‘s (and Freddie‘s) charter privileges against all comers – until the American Dream became Bailout America. TIMELINE Credit loosening Warning 1991 HUD Commission complains ―Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac‘s underwriting standards are oriented towards ‗plain vanilla‘ mortgage‖ [Read More] 1991 Lenders will respond to the most conservative standards unless [Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac] are aggressive and convincing in their efforts to expand historically narrow underwriting [Read More] 1992 Countrywide and Fannie Mae join forces to originate ―flexibly underwritten loans‖ [Read More] 1992 Congress passes -

Housing Finance Reform: Addressing a Growing Divide

08 Housing finance reform: Addressing a growing divide Barclays examines how United States housing finance policies affect homeownership rates, finding that affordability targets can provide an effective counterbalance to rising income inequality. 2 Foreword More than a decade after the mortgage-focused government- sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were placed under conservatorship during the 2008 Financial Crisis, the debate about the appropriate role of the government in the housing market continues. 13 October 2020 Despite a raft of housing policies including subsidies, taxes We draw several lessons from these results. First, the and mortgage guarantees, the US has similar homeownership government can positively influence housing outcomes. levels to other developed countries that do not offer such Second, the distinct effect of the GSE affordability targets support. Critics of the current policies cite this as evidence suggests that other forms of support, such as the FHA, may that government intervention accomplishes little except create not be sufficient for low income and minority borrowers in distortions in the housing market, and argue for a sharply their current form. reduced role for government going forward. From a housing policy perspective, this does not translate Yet an important structural difference between the US and into support for the status quo. Many interventions in the other developed economies is the high, and rising, level housing market should be reviewed and may be unnecessary, of income inequality in the US. Our analysis indicates that and we cannot ignore the lessons from the financial crisis rising inequality exerts significant downwards pressure and resulting bailouts. -

The Federal Reserve's Catch-22: 1 a Legal Analysis of the Federal Reserve's Emergency Powers

~ UNC Jill SCHOOL OF LAW *'/(! 4 --/! ,.%'! " ! ! " *''*1.$%-) %.%*)'1*,&-. $6+-$*',-$%+'1/)! /)% ,.*".$! )&%)#) %))!1*((*)- !*((!) ! %..%*) 5*(-*,.!, 7;:9;8;<= 0%''!. $6+-$*',-$%+'1/)! /)%0*' %-- 5%-*.!%-,*/#$..*2*/"*,",!!) *+!)!--2,*'%)1$*',-$%+!+*-%.*,2.$-!!)!+.! "*,%)'/-%*)%)*,.$,*'%) )&%)#)-.%./.!2)/.$*,%3! ! %.*,*",*'%)1$*',-$%+!+*-%.*,2*,(*,!%)"*,(.%*)+'!-!*).. '1,!+*-%.*,2/)! / The Federal Reserve's Catch-22: 1 A Legal Analysis of the Federal Reserve's Emergency Powers I. INTRODUCTION The federal government's role in the buyout of The Bear Stearns Companies (Bear) by JPMorgan Chase (JPMorgan) will be of lasting significance because it shaped a pivotal moment in the most threatening financial crisis since The Great Depression.2 On March 13, 2008, Bear informed "the Federal Reserve and other government agencies that its liquidity position had significantly deteriorated, and it would have to file for bankruptcy the next day unless alternative sources of funds became available."3 The potential impact of Bear's insolvency to the global financial system4 persuaded officials at the Federal Reserve (the Fed) and the United States Department of the Treasury (Treasury) to take unprecedented regulatory action.5 The response immediately 1. JOSEPH HELLER, CATCH-22 (Laurel 1989). 2. See Turmoil in the Financial Markets: Testimony Before the H. Oversight and Government Reform Comm., llO'h Cong. -- (2008) [hereinafter Greenspan Testimony] (statement of Dr. Alan Greenspan, former Chairman, Federal Reserve Board of Governors) ("We are in the midst of a once-in-a century credit tsunami."); Niall Ferguson, Wall Street Lays Another Egg, VANITY FAIR, Dec. 2008, at 190, available at http://www.vanityfair.com/politics/features/2008/12/banks200812 ("[B]eginning in the summer of 2007, [the global economy] began to self-destruct in what the International Monetary Fund soon acknowledged to be 'the largest financial shock since the Great Depression."'); Jeff Zeleny and Edmund L. -

Third Supplemental Information Memorandum Dated 23 July 2019

Third Supplemental Information Memorandum dated 23 July 2019 LVMH FINANCE BELGIQUE SA (incorporated as société anonyme / naamloze vennootschap) under the laws of Belgium, with enterprise number 0897.212.188 RPR/RPM (Brussels)) EUR 4,000,000,000 Belgian Multi-currency Short-Term Treasury Notes Programme Irrevocably and unconditionally guaranteed by LVMH Moët Hennessy - Louis Vuitton SE (incorporated as European company under the laws of France, and registered under number 775 670 417 (R.C.S. Paris)) The Programme is rated A-1 by Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services, a division of the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. and, Arranger Dealers Banque Fédérative du Crédit Mutuel BNP Paribas BRED Banque Populaire Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank Crédit Industriel et Commercial BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV Natixis Société Générale ING Belgium SA/NV ING Bank N.V. Belgian Branch Issuing and Paying Agent BNP Paribas Fortis SA/NV This third supplemental information memorandum is dated 23 July 2019 (the “Third Supplemental Information Memorandum”) and is supplemental to, and shall be read in conjunction with, the information memorandum dated 20 October 2015 as supplemented on 21 April 2016 and on 28 April 2017 (the “Information Memorandum”). Unless otherwise defined herein, terms defined in the Information Memorandum have the same respective meanings when used in this Third Supplemental Information Memorandum. As of the date of this Third Supplemental Information Memorandum: (i) The Issuer herby makes the following additional disclosure: Moody's assigned on 3 July 2019 a first-time A1 long-term issuer rating and Prime-1 (P-1) short-term rating to LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE.; (ii) The paragraph 1.17 “Rating(s) of the Programme” of the section entitled “1. -

Value, Caution and Accountability in an Era of Large Banks and Complex Finance*

2011-2012 BETTING BIG 765 BETTING BIG: VALUE, CAUTION AND ACCOUNTABILITY IN AN ERA OF LARGE BANKS AND COMPLEX FINANCE* LAWRENCE G. BAXTER** Abstract Big banks are controversial. Their supporters maintain that they offer products, services and infrastructure that smaller banks simply cannot match and enjoy unprecedented economies of scale and scope. Detractors worry about the risks generated by big banks, their threats to financial stability, and the way they externalize costs of operation to the public. This article explains why there is no conclusive argument one way or the other and why simple measures for restricting the danger of big banks are neither plausible nor effective. The complex ecology of modern finance and the management and regulatory challenges generated by ultra-large banking, however, cast serious doubt on the proposition that the benefits of big banking outweigh its risks. Consequently, two general principles are proposed for further consideration. First, big banks should bear a greater degree of public accountability by reforming certain principles of corporate governance to require greater representation of public interests at the board and executive levels of big banks. Second, given the unproven promises of performance by big banks, their unimpressive actual record of performance, and the many hazards they inevitably generate or encounter, financial regulators should consciously adopt a strict cautionary approach. Under this approach, big banks would bear a very heavy onus to demonstrate in concrete terms that their continued growth – and even the maintenance of their current scale – can be adequately managed and supervised. * © Lawrence G. Baxter. ** Professor of the Practice of Law, Duke Law School. -

Of Community Banking: the Continued Importance of Local Institutions Bob Solomon UC Irvine School of Law

UC Irvine Law Review Volume 2 Issue 3 Business Law as Public Interest Law / Article 8 Searching for Equality: A Conference on Law, Race, and Socio-Economic Class 12-2012 The alF l (and Rise?) of Community Banking: The Continued Importance of Local Institutions Bob Solomon UC Irvine School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Bob Solomon, The Fall (and Rise?) of Community Banking: The Continued Importance of Local Institutions, 2 U.C. Irvine L. Rev. 945 (2012). Available at: https://scholarship.law.uci.edu/ucilr/vol2/iss3/8 This Article and Essay is brought to you for free and open access by UCI Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UC Irvine Law Review by an authorized editor of UCI Law Scholarly Commons. UCILR V2I3 Assembled v8 (Do Not Delete) 12/14/2012 5:35 PM The Fall (and Rise?) of Community Banking: The Continued Importance of Local Institutions Bob Solomon* Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 945 I. The Reality of Bank Concentration .......................................................................... 946 II. Four Principles ........................................................................................................... 950 III. ShoreBank—The Model for Community Development Banking ................... 955 IV. The Difficulties of Starting a De Novo Bank— The New Haven Experience ........................................................................... -

China's 2020 Vision for Global Fund Managers

Markets and Securities Services | China’s 2020 vision for global fund managers 1 CHINA’S 2020 VISION FOR GLOBAL FUND MANAGERS Around 25 years ago, the authorities in China began to develop their capital markets ambitions. Stock exchanges were opened in Shanghai and Shenzhen. Members of the general public were allowed to buy stocks and shares on the market, albeit their choices at the time were limited to mainly (former) State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Talks also began for allowing the creation of mutual funds and the setting-up of fund management companies. Few would have believed, at the time, that by In July 2019, it was announced that the date for 2019 China’s stock markets in aggregate would 100% foreign ownership of fund management become one of the top-three largest in the companies would be brought forward to world by size and the largest by trading volume. sometime in 2020, and in October 2019 it was The aggregate scale of the assets managed in confirmed this would apply from April 2020. mutual funds, wealth management products and These announcements confirmed that non- other schemes made available to citizens now Chinese firms could own 100% of a Mainland exceeds approximately USD20 trillion. Chinese fund management company, allowing unrestricted access to offer investment services There’s a fantastic success story to be told. Yet and products to the retail market. for the most part, many of the top prizes to date have been reserved for domestic businesses in During the last three years, Chinese regulators China. Foreign firms, i.e. -

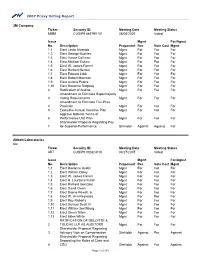

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: the Unmaking of America: a Recent History

Notes and Sources for Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America: A Recent History Introduction xiv “If infectious greed is the virus” Kurt Andersen, “City of Schemes,” The New York Times, Oct. 6, 2002. xvi “run of pedal-to-the-medal hypercapitalism” Kurt Andersen, “American Roulette,” New York, December 22, 2006. xx “People of the same trade” Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, ed. Andrew Skinner, 1776 (London: Penguin, 1999) Book I, Chapter X. Chapter 1 4 “The discovery of America offered” Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy In America, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (New York: Library of America, 2012), Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “A new science of politics” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Introductory Chapter. 4 “The inhabitants of the United States” Tocqueville, Democracy In America, Book One, Chapter XVIII. 5 “there was virtually no economic growth” Robert J Gordon. “Is US economic growth over? Faltering innovation confronts the six headwinds.” Policy Insight No. 63. Centre for Economic Policy Research, September, 2012. --Thomas Piketty, “World Growth from the Antiquity (growth rate per period),” Quandl. 6 each citizen’s share of the economy Richard H. Steckel, “A History of the Standard of Living in the United States,” in EH.net (Economic History Association, 2020). --Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies (New York: W.W. Norton, 2016), p. 98. 6 “Constant revolutionizing of production” Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969), Chapter I. 7 from the early 1840s to 1860 Tomas Nonnenmacher, “History of the U.S. -

Banking Type Feature Summary

Banking Type Feature Summary Citi Plus Citibanking Citi Priority Citigold Citigold Private Client Local Clients Relationship Balance No minimum balance No minimum balance To maintain the “Average Daily To maintain the “Average Daily To maintain the “Average Daily Requirement requirements. requirements. Combined Balance”1 of Combined Balance”1 of Combined Balance”1 of HK$500,000 or above. HK$1,500,000 or above. HK$8,000,000 or above. Monthly Service Fee No monthly service fee. No monthly service fee. No monthly service fee. HK$300 applied if the “Average HK$300 applied if the “Average Daily Combined Balance” falls Daily Combined Balance” falls below HK$1,500,000 for 3 below HK$1,500,000 for 3 consecutive months2. consecutive months2. International Personal Banking Clients3 Relationship Balance Not applicable to this banking Not applicable to this banking Not applicable to this banking To maintain the “Average Daily To maintain the “Average Daily Requirement type. type. type. Combined Balance”1 of Combined Balance”1 of HK$1,500,000 or above. HK$8,000,000 or above. Monthly Service Fee Not applicable to this banking HK$400 applied to all clients, HK$400 applied to all clients, HK$500 applied if the “Average HK$500 applied if the “Average type. irrespective of the clients' irrespective of the clients' Daily Combined Balance” falls Daily Combined Balance” falls “Average Daily Combined “Average Daily Combined below HK$1,500,000 for 3 below HK$1,500,000 for 3 Balance”4. Balance”4. consecutive months2. consecutive months2. All Clients Account Features - Enjoy Citi Interest Booster5 - Integrated banking services - Integrated banking services - Integrated banking services - Integrated banking services (an interest-bearing checking include saving and checking include saving and checking include saving and checking include saving and checking account) that you can boost the services. -

Citi Acquisition of Wachovia's Banking Operations

Citi Acquisition of Wachovia’s Banking Operations September 29, 2008 Transaction Structure Transaction Citi acquires Wachovia’s retail bank, corporate and investment bank and private bank Details businesses – Citi pays $2.2 billion to Wachovia in Citi common stock – Citi assumes substantially all of Wachovia’s debt; preferred stock excluded – Wachovia remains a publicly-traded holding company consisting of its retail brokerage and asset management businesses Capital Citi expects to raise $10 billion in common equity from the public markets Citi issues preferred stock and warrants to FDIC with a fair value of $12 billion at closing, accounted for as GAAP equity with full Tier 1 and leverage ratio benefit Quarterly dividend reduced to $0.16 per share immediately Regulatory capital relief on substantially all of the $312 billion of loss protected assets Risk Mitigation Citi enters loss protection arrangement with the FDIC on $312 billion of loss protected assets; maximum potential Citi losses of $42 billion – Citi is responsible for the first $30 billion of losses, recorded at closing through purchase accounting – Citi is responsible for the next $12 billion of losses, up to a maximum of $4 billion per year for the next three years – FDIC is responsible for any additional losses – Citi issues preferred stock and warrants to FDIC with a fair value of $12 billion at closing Approvals FDIC approved; subject to formal Federal Reserve approval and Wachovia shareholder approval Closing Anticipated by December 31, 2008 1 Terms of Loss Protection