Appendix E: Occ Supervision of Citibank, Na

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Pdf 707.34 KB

NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION IN OR INTO OR TO ANY PERSON LOCATED OR RESIDENT IN THE UNITED STATES, ITS TERRITORIES AND POSSESSIONS, ANY STATE OF THE UNITED STATES OR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA (INCLUDING PUERTO RICO, THE U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS, GUAM, AMERICAN SAMOA, WAKE ISLAND AND THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS) OR IN OR INTO OR TO ANY PERSON LOCATED OR RESIDENT IN ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DISTRIBUTE THIS DOCUMENT. EXOR N.V. ANNOUNCES FINAL RESULTS OF ITS TENDER OFFERS Amsterdam, 20 January 2021. EXOR N.V. (the Company) hereby announces the final results of its invitations to eligible Noteholders of its €750,000,000 2.125 per cent. Notes due 2 December 2022, ISIN XS1329671132 (of which €750,000,000 is currently outstanding) (the 2022 Notes) and its €650,000,000 2.50 per cent. Notes due 8 October 2024, ISIN XS1119021357 (of which €650,000,000 is currently outstanding) (the 2024 Notes, and together with the 2022 Notes, the Notes and each a Series) to tender their Notes for purchase by the Company for cash up to an aggregate maximum acceptance amount of €400,000,000 in aggregate nominal amount (the Maximum Acceptance Amount) (such invitations, the Offers and each an Offer). The Offers were announced on 12 January 2021 and were made on the terms and subject to the conditions set out in the tender offer memorandum dated 12 January 2021 (the Tender Offer Memorandum) prepared in connection with the Offers, and subject to the offer and distribution restrictions set out in the Tender Offer Memorandum. -

Citi Acquisition of Wachovia's Banking Operations

Citi Acquisition of Wachovia’s Banking Operations September 29, 2008 Transaction Structure Transaction Citi acquires Wachovia’s retail bank, corporate and investment bank and private bank Details businesses – Citi pays $2.2 billion to Wachovia in Citi common stock – Citi assumes substantially all of Wachovia’s debt; preferred stock excluded – Wachovia remains a publicly-traded holding company consisting of its retail brokerage and asset management businesses Capital Citi expects to raise $10 billion in common equity from the public markets Citi issues preferred stock and warrants to FDIC with a fair value of $12 billion at closing, accounted for as GAAP equity with full Tier 1 and leverage ratio benefit Quarterly dividend reduced to $0.16 per share immediately Regulatory capital relief on substantially all of the $312 billion of loss protected assets Risk Mitigation Citi enters loss protection arrangement with the FDIC on $312 billion of loss protected assets; maximum potential Citi losses of $42 billion – Citi is responsible for the first $30 billion of losses, recorded at closing through purchase accounting – Citi is responsible for the next $12 billion of losses, up to a maximum of $4 billion per year for the next three years – FDIC is responsible for any additional losses – Citi issues preferred stock and warrants to FDIC with a fair value of $12 billion at closing Approvals FDIC approved; subject to formal Federal Reserve approval and Wachovia shareholder approval Closing Anticipated by December 31, 2008 1 Terms of Loss Protection -

Kevin Bonebrake Joins Lazard As a Managing Director in Oil and Gas Financial Advisory

KEVIN BONEBRAKE JOINS LAZARD AS A MANAGING DIRECTOR IN OIL AND GAS FINANCIAL ADVISORY NEW YORK, January 11, 2017 – Lazard Ltd (NYSE: LAZ) announced today that Kevin Bonebrake has joined the firm as a Managing Director, Financial Advisory, effective immediately. Based in Houston, he will advise companies in the oil and gas sector on mergers and acquisitions and other financial matters. “As the energy industry continues to undergo transformative change, Lazard has been advising clients on a growing number of both strategic transactions and restructuring assignments,” said Matt Lustig, head of North American Investment Banking at Lazard. “Kevin will be a strong addition to our Houston team and enhance our ability to advise our energy clients worldwide.” Mr. Bonebrake has more than 12 years of energy-sector advisory experience, with a focus on North American independent exploration & production companies, majors and national oil companies. He joins Lazard from Morgan Stanley, where he was most recently a Managing Director in the firm’s Global Natural Resources practice within the Investment Banking Division. Between 2003 and 2009 he worked for Salomon Smith Barney/Citigroup as a member of its Global Energy Investment Banking team. About Lazard Lazard, one of the world’s preeminent financial advisory and asset management firms, operates from 42 cities across 27 countries in North America, Europe, Asia, Australia, Central and South America. With origins dating to 1848, the firm provides advice on mergers and acquisitions, strategic matters, restructuring and capital structure, capital raising and corporate finance, as well as asset management services to corporations, partnerships, institutions, governments and individuals. -

Citigroup Inc. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2010 Commission file number 1-9924 Citigroup Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 52-1568099 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 399 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10043 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (212) 559-1000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: See Exhibit 99.01 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: none Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes X No Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes X No Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. X Yes No Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to submit and post such files). -

Citigroup: a Case Study in Managerial and Regulatory Failures

CITIGROUP: A CASE STUDY IN MANAGERIAL AND REGULATORY FAILURES ARTHUR E. WILMARTH, JR.* “I don’t think [Citigroup is] too big to manage or govern at all . [W]hen you look at the results of what happened, you have to say it was a great success.” Sanford “Sandy” Weill, chairman of Citigroup, 1998-20061 “Our job is to set a tone at the top to incent people to do the right thing and to set up safety nets to catch people who make mistakes or do the wrong thing and correct those as quickly as possible. And it is working. It is working.” Charles O. “Chuck” Prince III, CEO of Citigroup, 2003-20072 “People know I was concerned about the markets. Clearly, there were things wrong. But I don’t know of anyone who foresaw a perfect storm, and that’s what we’ve had here.” Robert Rubin, chairman of Citigroup’s executive committee, 1999- 20093 “I do not think we did enough as [regulators] with the authority we had to help contain the risks that ultimately emerged in [Citigroup].” Timothy Geithner, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2003-2009; Secretary of the Treasury, 2009-20134 * Professor of Law and Executive Director of the Center for Law, Economics & Finance, George Washington University Law School. I wish to thank GW Law School and Dean Greg Maggs for a summer research grant that supported my work on this Article. I am indebted to Eric Klein, a member of GW Law’s Class of 2015, and Germaine Leahy, Head of Reference in the Jacob Burns Law Library, for their superb research assistance. -

Must Be Printed on Citi Personal Wealth Management Letterhead

Luis Bedoya 153 E 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022 212-559-6944 Citigroup Global Markets Inc. (“CGMI”) – Citi Personal Wealth Management August 2016 This brochure supplement provides information about Luis Bedoya that supplements the firm’s Form ADV Part 2 brochure. You should have received a copy of that brochure. You may obtain an additional copy of that brochure on the SEC’s website at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov by searching the name “Citigroup Global Markets Inc.” in the Investment Adviser Firm section. If you would like us to send you an additional copy of the brochure please call 1-877-357-3399.If you have any questions about the contents of this supplement, please contact the supervising person listed at the end this supplement. If the individual is registered as investment adviser in one or more states, additional information about the representative is available on the SEC’s website at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov by entering his or her name into the representative search. More information may be available on the BrokerCheck website at www.finra.org/Investors/ToolsCalculators/BrokerCheck/. Educational Background and Business Experience Luis Bedoya, born 1968 Educational Background -Bachelors in Economics, National University of Cordoba-Argentina, 1994 -MBA, ESAN University-Peru, 1997 -Certificate of Special Studies of Administration and Management, Harvard University, 2004 Business Experience -Financial Advisor, Citigroup, 2013-Present -International Financial Advisor, Merrill Lynch, 2011-2013 -Director International Sales, World Party - Iluminaciones Italicas, 2007-2011 -VP MArketing and Strategy, DIB, 2004-2007 Luis Bedoya also holds the following licenses: The Series 7 license is granted to persons who pass the General Securities Representative Examination administered by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, Inc. -

Administrative Proceeding: Bear, Stearns & Co. Inc.; Citigroup Global

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Before the SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 Release No. 8684 / May 31, 2006 SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Release No. 53888 / May 31, 2006 ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEEDING File No. 3-12310 ORDER INSTITUTING In the Matter of ADMINISTRATIVE AND CEASE-AND-DESIST BEAR, STEARNS & CO. INC.; CITIGROUP PROCEEDINGS, MAKING GLOBAL MARKETS, INC.; GOLDMAN, FINDINGS, AND IMPOSING SACHS & CO.; J.P. MORGAN SECURITIES, REMEDIAL SANCTIONS AND INC.; LEHMAN BROTHERS INC.; A CEASE-AND-DESIST ORDER MERRILL LYNCH, PIERCE, FENNER & PURSUANT TO SECTION 8A SMITH INCORPORATED; MORGAN OF THE SECURITIES ACT OF STANLEY & CO. INCORPORATED AND 1933 AND SECTION 15(b) OF MORGAN STANLEY DW INC.; RBC DAIN THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE RAUSCHER INC.; BANC OF AMERICA ACT OF 1934 SECURITIES LLC; A.G. EDWARDS & SONS, INC.; MORGAN KEEGAN & COMPANY, INC.; PIPER JAFFRAY & CO.; SUNTRUST CAPITAL MARKETS INC.; AND WACHOVIA CAPITAL MARKETS, LLC, Respondents. I. The Securities and Exchange Commission (“Commission”) deems it appropriate and in the public interest that public administrative and cease-and-desist proceedings be, and hereby are, instituted pursuant to Section 8A of the Securities Act of 1933 (“Securities Act”) and Section 15(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (“Exchange Act”) against Bear, Stearns & Co. Inc.; Citigroup Global Markets, Inc.; Goldman, Sachs & Co.; J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc.; Lehman Brothers Inc.; Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith Incorporated; Morgan Stanley & Co. Incorporated and Morgan Stanley DW Inc.; RBC Dain Rauscher Inc.; Banc of America Securities LLC; A.G. Edwards & Sons, Inc.; Morgan Keegan & Company, Inc.; Piper Jaffray & Co.; SunTrust Capital Markets Inc.; and Wachovia Capital Markets, LLC (“Respondents”). -

Did Repeal of Glass-Steagall for Citigroup Exacerbate the Crisis?

ETHICS Curtis C. Verschoor, CMA, Editor Did Repeal of Glass-Steagall for Citigroup Exacerbate Freed from the restrictions of the Glass-Steagall Act, giant bank- the Crisis? holding companies appear to have been focused more on industry should be recognized as Citibank and Travelers Group. In meeting the expectations of Wall at least a quasi-public utility, exist- addition to the traditional bank- Street analysts than on protect- ing in large part for the benefit of ing services, this $140 billion ing depositors’ funds from risk. depositors who need to have con- umbrella encompassed brokerage, tinuing confidence that their investment banking, and several funds are safe. insurance companies, including mid the finger-pointing After the savings and loan disas- Travelers. Agoing on in regard to the cur- ter caused the previous banking More recently, urged on by for- rent banking crisis, it seems that debacle, the FDIC Improvement mer U.S. Treasury Secretary we may be forgetting who the real Act of 1991 mandated that insured Robert Rubin, Citigroup’s director culprits are. Should we blame the institutions employ adequate con- and chair of its Executive Com- bungling bureaucrats in Fannie trols to manage their risks in order mittee, Citi acquired heavy expo- Mae, Freddie Mac, the Federal to maintain the safety and sound- sure to Collateralized Debt Oblig- Reserve, the Securities & Exchange ations (CDOs) based on subprime Commission (SEC), and the Trea- mortgages. By 2006, Citi had sury Department? Or are the regu- It will take a major become the second largest under- lators (perhaps they should be overhaul of business writer of CDOs. -

Randall Complaint

Vito Torchia, Jr. (SBN244687) 1 [email protected] BROOKSTONE LAW, PC 2 18831 Von Karman Ave., Suite 400 Irvine, CA 92612 3 Telephone: (800) 946-8655 Facsimile: (866) 257-6172 4 E-mail: [email protected] 5 Attorneys for Plaintiffs 6 7 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 8 COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES 9 BC526888 10 DOUGLAS RANDALL, an individual; Case No.: LOLITA RANDALL, an individual; MARK 11 COMPLAINT FOR: GENNARO, an individual; MANUEL 12 SEDILLOS, an individual; MICHELLE 1. INTENTIONAL PLACEMENT OF ROGERS, an individual; ANTONIO BORROWERS INTO DANGEROUS LOANS 13 HERNANDEZ, an individual; DONNA THEY COULD NOT AFFORD THROUGH COORDINATED DECEPTION, IN THE NAME 14 HERNANDEZ, an individual; LAURO OF MAXIMIZING LOAN VOLUME AND THUS ROBERTO, an individual; AMALIA PROFIT 15 ROBERTO, an individual; VINCENT COUNTl-FRAUDULENTCONCEALMENT LOMBARDO, an individual; LORRAINE 16 LOMBARDO, an individual; SHIRLEY COUNT 2- INTENTIONAL MISREPRESENTATION 17 COFFEY, an individual; DINA GARAY, an individual; JAMES FORTIER, an COUNT 3- NEGLIGENT MISREPRESENTATION 18 individual; ANGEL DIAZ, an individual; COUNT 4- NEGLIGENCE ALICE SHIOTSUGU, an individual; 19 VICENTE PINEDA, an individual; JERRY COUNT 5- UNFAIR, UNLAWFUL, AND FRAUDULENT BUSINESS PRACTICES 20 ROGGE, an individual; MICHAEL (VIOLATION OF CAL. BUS. & PROF. CODE SHAFFER, an individual; VICTORIA §17200) 21 ARCADI, an individual; DEBORAH 2; INDIVIDUAL APPRAISAL INFLATION BECKER, an individual; YOUSEF 22 LAZARIAN, an individual; LINAT COUNT 6- INTENTIONAL 23 LAZARIAN, an individual; DIANA MISREPRESENTATION BOGDEN, an individual; SHILA COUNT 7-NEGLIGENTMISREPRESENTATION 24 ARDALAN, an individual; GEORGE COUNT 8- NEGLIGENCE 25 CHRIPCZUK, an individual; ROBERT ORNELAS, an individual; LICET COUNT 9- UNFAIR, UNLAWFUL, AND FRAUDULENT BUSINESS PRACTICES ORNELAS, an individual; AMIE GA YE, an 26 (VIOLATION OF CAL. -

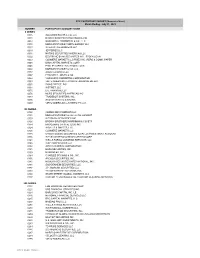

Numerical.Pdf

DTC PARTICPANT REPORT (Numerical Sort ) Month Ending - July 31, 2021 NUMBER PARTICIPANT ACCOUNT NAME 0 SERIES 0005 GOLDMAN SACHS & CO. LLC 0010 BROWN BROTHERS HARRIMAN & CO. 0013 SANFORD C. BERNSTEIN & CO., LLC 0015 MORGAN STANLEY SMITH BARNEY LLC 0017 INTERACTIVE BROKERS LLC 0019 JEFFERIES LLC 0031 NATIXIS SECURITIES AMERICAS LLC 0032 DEUTSCHE BANK SECURITIES INC.- STOCK LOAN 0033 COMMERZ MARKETS LLC/FIXED INC. REPO & COMM. PAPER 0045 BMO CAPITAL MARKETS CORP. 0046 PHILLIP CAPITAL INC./STOCK LOAN 0050 MORGAN STANLEY & CO. LLC 0052 AXOS CLEARING LLC 0057 EDWARD D. JONES & CO. 0062 VANGUARD MARKETING CORPORATION 0063 VIRTU AMERICAS LLC/VIRTU FINANCIAL BD LLC 0065 ZIONS DIRECT, INC. 0067 INSTINET, LLC 0075 LPL FINANCIAL LLC 0076 MUFG SECURITIES AMERICAS INC. 0083 TRADEBOT SYSTEMS, INC. 0096 SCOTIA CAPITAL (USA) INC. 0099 VIRTU AMERICAS LLC/VIRTU ITG LLC 100 SERIES 0100 COWEN AND COMPANY LLC 0101 MORGAN STANLEY & CO LLC/SL CONDUIT 0103 WEDBUSH SECURITIES INC. 0109 BROWN BROTHERS HARRIMAN & CO./ETF 0114 MACQUARIE CAPITAL (USA) INC. 0124 INGALLS & SNYDER, LLC 0126 COMMERZ MARKETS LLC 0135 CREDIT SUISSE SECURITIES (USA) LLC/INVESTMENT ACCOUNT 0136 INTESA SANPAOLO IMI SECURITIES CORP. 0141 WELLS FARGO CLEARING SERVICES, LLC 0148 ICAP CORPORATES LLC 0158 APEX CLEARING CORPORATION 0161 BOFA SECURITIES, INC. 0163 NASDAQ BX, INC. 0164 CHARLES SCHWAB & CO., INC. 0166 ARCOLA SECURITIES, INC. 0180 NOMURA SECURITIES INTERNATIONAL, INC. 0181 GUGGENHEIM SECURITIES, LLC 0187 J.P. MORGAN SECURITIES LLC 0188 TD AMERITRADE CLEARING, INC. 0189 STATE STREET GLOBAL MARKETS, LLC 0197 CANTOR FITZGERALD & CO. / CANTOR CLEARING SERVICES 200 SERIES 0202 FHN FINANCIAL SECURITIES CORP. 0221 UBS FINANCIAL SERVICES INC. -

Citigroup Settles with DOJ for Illicit Mortgage Activities in 2006 and 2007

2014-2015 DEVELOPMENTS IN BANKING LAW 57 VI. Citigroup Settles with DOJ for Illicit Mortgage Activities in 2006 and 2007 A. Introduction In 2006 and 2007, financial institutions—including Citigroup Inc. (“Citigroup”)—engaged in massive subprime lending of mortgage backed securities.1 According to the Department of Justice (“DOJ”), Citigroup failed to perform proper due diligence and comply with certain state and federal laws, primarily through misrepresentations concerning the quality of their loans.2 Citigroup often combined these loans together as mortgage backed securities that were in turn sold to other investors.3 This allowed Citigroup to dodge the financial ramifications of their failed loans.4 Lender misrepresentations, such as those Citigroup made, led to a major wave of mortgage defaults in 2007, causing housing prices to plummet and igniting a complete market crisis.5 Citigroup is among a number of large banks that recently settled DOJ charges that they engaged in illicit mass subprime lending and significantly contributed to the recent financial crisis.6 Pursuant to the DOJ settlement, Citigroup must pay $7 billion dollars that will go to the U.S. government and towards initiatives to help homeowners 1 U.S. DEP’T OF JUSTICE, CITIGROUP SETTLEMENT: STATEMENT OF FACTS 1 (2014) [hereinafter STATEMENT OF FACTS], available at http://www.justice. gov/iso/opa/resources/558201471413645397758.pdf, archived at http://perma.cc/Y2PJ-7DJS. 2 Id. 3 Id. 4 See Steven L. Schwarcz, The Future of Securitization, 41 CONN. L. REV. 1313, 1318–21 (2009) (discussing how the originate-to-distribute model creates moral hazard issues for banks like Citigroup, by allowing banks to avoid the consequences when borrowers default). -

Biography John Heppolette Managing Director 212-723-4205 [email protected]

Biography John Heppolette Managing Director 212-723-4205 [email protected] John Heppolette is Co-Head of Citi Community Capital, the community development lending and investing division of Citi, with over 20 years of experience in the municipal, non-profit and real estate markets. He sits on Citibank’s firm-wide Fair Lending and CRA Committee and is a Public Policy Advisory Board member for the NYU Furman Center. John began his career with Lazard Freres in New York as an investment banker focused on modeling of municipal financings and corporate restructurings. He then worked on municipal derivatives and structured financings for TMG Financial Products in Connecticut and JP Morgan in New York before arriving at Citi (then Salomon Smith Barney) in 1998. Since that time, John has held a variety of positions within Citi, including affordable housing finance, municipal bond and derivative trading, structured financings, credit products and portfolio management. In John’s role as Co-Head of Citi Community Capital he directs the activities of the unit’s affordable rental housing lending, mortgage and investment banking team, as well as its involvement with Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC), New Market Tax Credits (NMTC) and other Community Reinvestment Act lending and investing activities. John holds a BSc in Electrical Engineering and a BA in Economics from Queen’s University in Canada, as well as an MEng in Operations Research and MBA in Finance from Cornell University. Citi Community Capital citicomunitycapital.com © 2017 Citigroup Global Markets Inc. Member SIPC. All rights reserved. Citi and Citi and Arc Design are trademarks and service marks of Citigroup Inc.