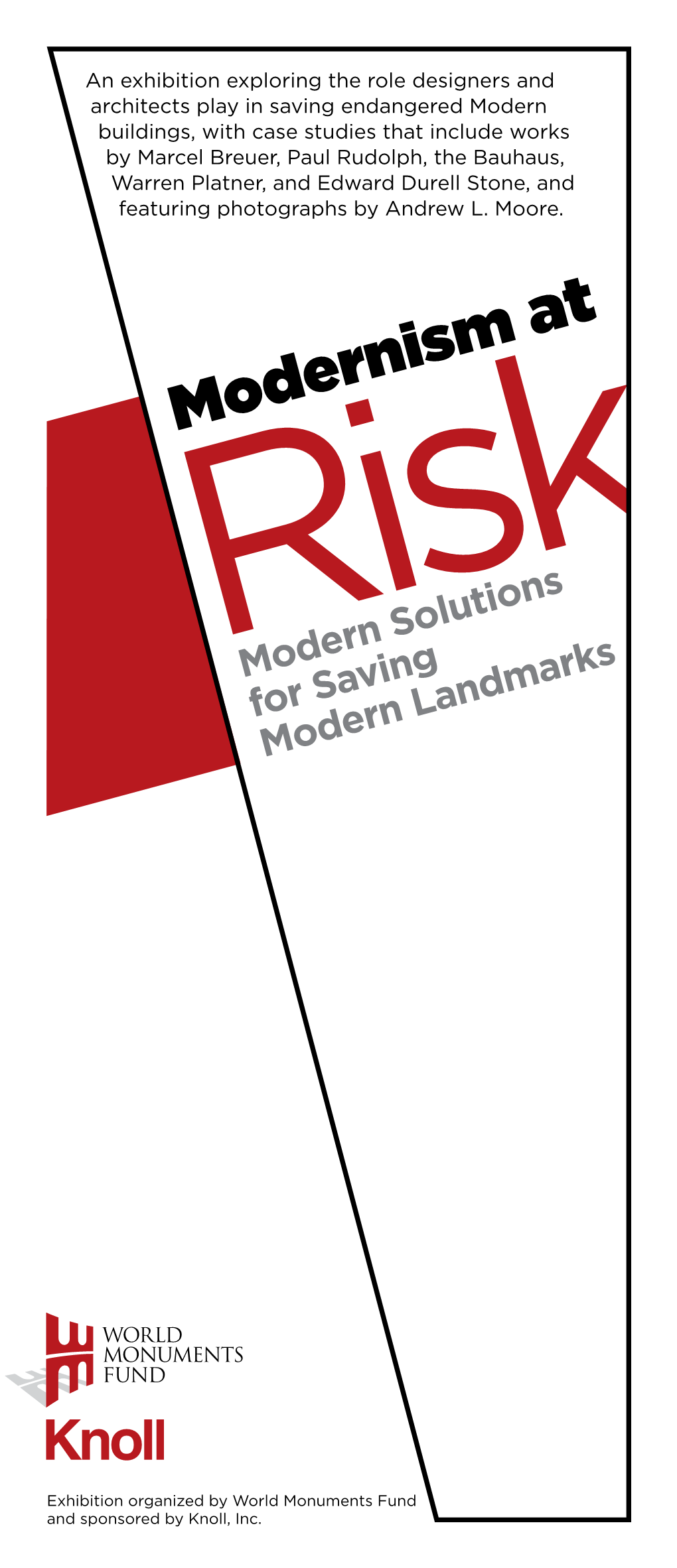

An Exhibition Exploring the Role Designers and Architects Play In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

A Finding Aid to the Perls Galleries Records, 1937-1997, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Perls Galleries Records, 1937-1997, in the Archives of American Art Julie Schweitzer January 15, 2009 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1937-1995.................................................................... 5 Series 2: Negatives, circa 1937-1995.................................................................. 100 Series 3: Photographs, circa 1937-1995.............................................................. 142 Series 4: Exhibition, Loan, and Sales Records, 1937-1995................................ -

Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism IC I ICOMOS COMOS O M OS

Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne Welterbevorschläge aus Mittel- und Osteuropa Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism World Heritage Proposals from Central and Eastern Europe Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne SocialistSocialist Modernism Realism and III V L S EE T MI O ALK N O I T A N N E CH S UT E D S ICOMOS · HEFTE DES DEUTSCHEN NATIONALKOMITEES LVIII ICOMOS · JOURNALS OF THE GERMAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE LVIII ICOMOS · HEFTE DE ICOMOS ICOMOS · CAHIERS DU COMITÉ NATIONAL ALLEMAND LVIII Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism I NTERNATIONAL COUNCIL on MONUMENTS and SITES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SITES CONSEJO INTERNACIONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SITIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст Sozialistischer Realismus und Sozialistische Moderne. Welterbevorschläge aus Mittel- und Osteuropa Dokumentation des europäischen Expertentreffens von ICOMOS über Möglichkeiten einer internationalen seriellen Nominierung von Denkmalen und Stätten des 20. Jahrhunderts in postsozialistischen Ländern für die Welterbeliste der UNESCO – Warschau, 14.–15. April 2013 – Socialist Realism and Socialist Modernism. World Heritage Proposals from Central and Eastern Europe Documentation of the European expert meeting of ICOMOS on the feasibility of an international serial nomination of 20th century monuments and sites in post-socialist countries for the UNESCO World Heritage List – Warsaw, 14th–15th of April 2013 – ICOMOS · H E F T E des D E U T S CHEN N AT I ONAL KO MI T E E S LVIII ICOMOS · JOURNALS OF THE GERMAN NATIONAL COMMITTEE LVIII ICOMOS · CAHIERS du COMITÉ NATIONAL ALLEMAND LVIII ICOMOS Hefte des Deutschen Nationalkomitees Herausgegeben vom Nationalkomitee der Bundesrepublik Deutschland Präsident: Prof. -

Hannes Meyer's Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at The

Hannes Meyer’s Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at the Bauhaus (1927-1930) Hideo Tomita The Second Asian Conference of Design History and Theory —Design Education beyond Boundaries— ACDHT 2017 TOKYO 1-2 September 2017 Tsuda University Hannes Meyer’s Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at the Bauhaus (1927-1930) Hideo Tomita Kyushu Sangyo University [email protected] 29 Abstract Although the Bauhaus’s second director, Hannes Meyer (1889-1954), as well as some of the graduates whom he taught, have been much discussed in previous literature, little is known about the architectural education that Meyer shaped during his tenure. He incorporated key concepts from biology, psychology, and sociology, and invited specialists from a wide variety of fields. The Bauhaus under Meyer was committed to what is considered a “scientific world- view,” and this study focuses on how Meyer incorporated this into his theory of architectural education. This study reveals the following points. First, Meyer and his students used sociology to design analytic architectural diagrams and spatial standardizations. Second, they used psy- chology to design spaces that enabled people to recognize a symbolized community, to grasp a social organization, and to help them relax their mind. Third, Meyer and his students used hu- man biology to decide which direction buildings should face and how large or small that rooms and windows should be. Finally, Meyer’s unified scientific worldview shared a similar theoreti- cal structure to the “unity of science” movement, established by the founding members of the Vienna Circle, at a conceptual level. Keywords: Bauhaus, Architectural Education, Sociology, Psychology, Biology, Unity of Science Hannes Meyer’s Scientific Worldview and Architectural Education at the Bauhaus (1927–1930) 30 The ACDHT Journal, No.2, 2017 Introduction In 1920s Germany, modernist architects began to incorporate biology, sociology, and psychol- ogy into their architectural theory based on the concept of “function” (Gropius, 1929; May, 1929). -

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian American Art Museum Chronological List of Past Exhibitions and Installations on View at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery 1958-2016 ■ = EXHIBITION CATALOGUE OR CHECKLIST PUBLISHED R = RENWICK GALLERY INSTALLATION/EXHIBITION May 1921 xx1 American Portraits (WWI) ■ 2/23/58 - 3/16/58 x1 Paul Manship 7/24/64 - 8/13/64 1 Fourth All-Army Art Exhibition 7/25/64 - 8/13/64 2 Potomac Appalachian Trail Club 8/22/64 - 9/10/64 3 Sixth Biennial Creative Crafts Exhibition 9/20/64 - 10/8/64 4 Ancient Rock Paintings and Exhibitions 9/20/64 - 10/8/64 5 Capital Area Art Exhibition - Landscape Club 10/17/64 - 11/5/64 6 71st Annual Exhibition Society of Washington Artists 10/17/64 - 11/5/64 7 Wildlife Paintings of Basil Ede 11/14/64 - 12/3/64 8 Watercolors by “Pop” Hart 11/14/64 - 12/13/64 9 One Hundred Books from Finland 12/5/64 - 1/5/65 10 Vases from the Etruscan Cemetery at Cerveteri 12/13/64 - 1/3/65 11 27th Annual, American Art League 1/9/64 - 1/28/65 12 Operation Palette II - The Navy Today 2/9/65 - 2/22/65 13 Swedish Folk Art 2/28/65 - 3/21/65 14 The Dead Sea Scrolls of Japan 3/8/65 - 4/5/65 15 Danish Abstract Art 4/28/65 - 5/16/65 16 Medieval Frescoes from Yugoslavia ■ 5/28/65 - 7/5/65 17 Stuart Davis Memorial Exhibition 6/5/65 - 7/5/65 18 “Draw, Cut, Scratch, Etch -- Print!” 6/5/65 - 6/27/65 19 Mother and Child in Modern Art ■ 7/19/65 - 9/19/65 20 George Catlin’s Indian Gallery 7/24/65 - 8/15/65 21 Treasures from the Plantin-Moretus Museum Page 1 of 28 9/4/65 - 9/25/65 22 American Prints of the Sixties 9/11/65 - 1/17/65 23 The Preservation of Abu Simbel 10/14/65 - 11/14/65 24 Romanian (?) Tapestries ■ 12/2/65 - 1/9/66 25 Roots of Abstract Art in America 1910 - 1930 ■ 1/27/66 - 3/6/66 26 U.S. -

Tear It Down! Save It! Preservationists Have Gained the Upper Hand in Protecting Historic Buildings

Tear It Down! Save It! Preservationists have gained the upper hand in protecting historic buildings. Now the ques- tion is whether examples of modern architecture— such as these three buildings —deserve the same respect as the great buildings of the past. By Larry Van Dyne The church at 16th and I streets in downtown DC does not match the usual images of a vi- sually appealing house of worship. It bears no resemblance to the picturesque churches of New England with their white clapboard and soaring steeples. And it has none of the robust stonework and stained-glass windows of a Gothic cathedral. The Third Church of Christ, Scientist, is modern architecture. Octagonal in shape, its walls rise 60 feet in roughcast concrete with only a couple of windows and a cantilevered carillon interrupting the gray façade. Surrounded by an empty plaza, it leaves the impression of a supersized piece of abstract sculpture. The church sits on a prime tract of land just north of the White House. The site is so valua- ble that a Washington-based real-estate company, ICG Properties, which owns an office building next door, has bought the land under the church and an adjacent building originally owned by the Christian Science home church in Boston. It hopes to cut a deal with the local church to tear down its sanctuary and fill the assembled site with a large office complex. The congregation, which consists of only a few dozen members, is eager to make the deal — hoping to occupy a new church inside the complex. -

Shifts in Modernist Architects' Design Thinking

arts Article Function and Form: Shifts in Modernist Architects’ Design Thinking Atli Magnus Seelow Department of Architecture, Chalmers University of Technology, Sven Hultins Gata 6, 41296 Gothenburg, Sweden; [email protected]; Tel.: +46-72-968-88-85 Academic Editor: Marco Sosa Received: 22 August 2016; Accepted: 3 November 2016; Published: 9 January 2017 Abstract: Since the so-called “type-debate” at the 1914 Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne—on individual versus standardized types—the discussion about turning Function into Form has been an important topic in Architectural Theory. The aim of this article is to trace the historic shifts in the relationship between Function and Form: First, how Functional Thinking was turned into an Art Form; this orginates in the Werkbund concept of artistic refinement of industrial production. Second, how Functional Analysis was applied to design and production processes, focused on certain aspects, such as economic management or floor plan design. Third, how Architectural Function was used as a social or political argument; this is of particular interest during the interwar years. A comparison of theses different aspects of the relationship between Function and Form reveals that it has undergone fundamental shifts—from Art to Science and Politics—that are tied to historic developments. It is interesting to note that this happens in a short period of time in the first half of the 20th Century. Looking at these historic shifts not only sheds new light on the creative process in Modern Architecture, this may also serve as a stepstone towards a new rethinking of Function and Form. Keywords: Modern Architecture; functionalism; form; art; science; politics 1. -

Ray Bromley Edward Durell Stone. from the International Style to a Personal Style1

DOI: 10.1283/fam/issn2039-0491/n47-2019/231 Ray Bromley Edward Durell Stone. From the International Style to a Personal style1 Abstract Edward Durell Stone (1902-1978) was an American modernist who devel- oped a unique signature style of ‘new romanticism’ during the middle phase of his career between 1954 and 1966. The style was employed in several dozen major architectural projects and it coincided with his second marriage. His first signature style project was the U.S. Embassy in New Delhi, and the most famous one is the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington D.C. He achieved temporary global renown with his design for the U.S. Pavilion at the Brussels World’s Fair in 1958. Sadly, his best projects are widely scattered and he has no significant signature style works in New York City, where he based his career. His current obscurity is explained by the eccentric character of his signature style, his transition from personal design to corporate replication, and the abandonment of signature design principles after the breakdown of his second marriage. Key-words Modernism — New Romanticism — Signature Style Edward Durell Stone (EDS, 1902-1978) was an American modernist and post-modernist architect, who studied art and architecture at the University of Arkansas, Harvard and M.I.T., but who never completed an academic degree. The high point of his student days was a two year 1927-1929 Rotch Fellowship to tour Europe, focusing mainly on the Mediterranean countries, and preparing many fine architectural renderings of historic buildings. His European travels and Rotch Fellowship drawings reflected a deep appreciation of Beaux Arts traditions, but also a growing interest in modernist architecture and functionalist ideals. -

NCN Articles of Interest | June 4, 2021

ARTICLES OF INTEREST June 4, 2021 QUOTE(S) OF THE WEEK “Creativity is not simply a property of exceptional people but an exceptional property of all people” – Ron Carter “Hire/promote for demonstrated curiosity.” – Tom Peters “Mathematics is not about numbers, equations, computations, or algorithms: it is about understanding.” – William Paul Thurston “If the Internet teaches us anything, it is that great value comes from leaving core resources in a commons, where they're free for people to build upon as they see fit.” – Lawrence Lessig “Love the battle between chaos and imagination.” – Robert Fulghum VIDEO(S) OF THE WEEK Discussion on Harnessing Culture and Heritage for economic transformation UN Office of the Special Adviser on Africa Bug Expert Explains Why Cicadas Are So Loud WIRED 5 Minutes That Will Make You Love Percussion The New York Times The Right Stuff: What It Takes to Boldly Go World Science Festival Cosmology and the Accelerating Universe | A Conversation with Nobel Laureate Brian Schmidt World Science Festival Meera Lee Patel: Making Friends with Your Fear CreativeMorning | Nashville FEATURED EVENTS/OPPORTUNITIES Viewfinder: Women’s Film and Video from the Smithsonian Because of HER Story | Smithsonian Monthly Series | First Thursday of the Month Black creatives never stopped creating Chicago Reader Through July 4 NEW Join Us for a Live Webinar on Famous 'Late Bloomers' and the Secrets of Midlife Creativity Smithsonian Magazine Event June 8 at 7 p.m. ET NEW Author and neurobiologist to discuss Art and the Brain June 8 Cape -

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity the Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity The Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Upholstery, drapery, and wall-covering samples 1923-29 Wool, rayon, cotton, linen, raffia, cellophane, and chenille Between 8 1/8 x 3 1/2" (20.6 x 8.9 cm) and 4 3/8 x 16" (11.1 x 40.6 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the designer or Gift of Josef Albers ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Silk, cotton, and acetate 57 1/8 x 36 1/4" (145 x 92 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Wool and silk 7' 8 7.8" x 37 3.4" (236 x 96 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1926 Silk (three-ply weave) 70 3/8 x 46 3/8" (178.8 x 117.8 cm) Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Association Fund Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity - Exhibition Checklist 10/27/2009 Page 1 of 80 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Tablecloth Fabric Sample 1930 Mercerized cotton 23 3/8 x 28 1/2" (59.3 x 72.4 cm) Manufacturer: Deutsche Werkstaetten GmbH, Hellerau, Germany The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase Fund JOSEF ALBERS German, 1888-1976; at Bauhaus 1920–33 Gitterbild I (Grid Picture I; also known as Scherbe ins Gitterbild [Glass fragments in grid picture]) c. -

The Visitor's Guide to the Florida Capitol

The VisitFloridaCapitol.com Visitor’s Guide to the Florida Capitol The VisitFloridaCapitol.com Visitor’s Guide to the Florida Capitol presented by VISIT FLORIDA PRESENTED BY Contents Welcome .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Capitol Information .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Times of Operation............................................................................................................................................... 5 State Holidays Closed .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Frequently Asked Questions ................................................................................................................................. 6 Capitol Grounds Map ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Artwork in the Capitol ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Your Event at the Capitol ................................................................................................................................... 10 Security ............................................................................................................................................................. -

Russian Constructivism

De Stijl in the Netherlands Russian Constructivism 26 Constructivism was an artistic and architectural movement that originated in Russia from 1919 onward which rejected the idea of "art for art's sake" in favour of art as a practice directed towards social purposes and uses. Constructivism as an active force lasted until around 1934, having a great deal of effect on developments in the art of the Weimar Republic (post world war one Germany) and elsewhere, before being replaced by Socialist Realism. Its motifs have sporadically recurred in other art movements since. It had a lasting impact on modern design through some of its members becoming involved with the Bauhaus group. Constructivism had a particularly lasting effect on typography and graphic design. Constructivism art refers to the optimistic, non-representational relief construction, sculpture, kinetics and painting. The artists did not believe in abstract ideas, rather they tried to link art with concrete and tangible ideas. Early modern movements around WWI were idealistic, seeking a new order in art and architecture that dealt with social and economic problems. They wanted to renew the idea that the apex of artwork does not revolve around "fine art", but rather emphasized that the most priceless artwork can often be discovered in the nuances of "practical art" and through portraying man and mechanization into one aesthetic program. Constructivism was first created in Russia in 1913 when the Russian sculptor Vladimir Tatlin, during his journey to Paris, discovered the works of Braque and Picasso. When Tatlin was back in Russia, he began producing sculptured out of assemblages, but he abandoned any reference to precise subjects or themes.