Absorption and Assimilation: Australia's Aboriginal Policies in the 19Th and 20Th Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboriginal History Journal

ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume 38, 2014 ABORIGINAL HISTORY Volume 38, 2014 Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://press.anu.edu.au All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Editor Shino Konishi, Book Review Editor Luise Hercus, Copy Editor Geoff Hunt. About Aboriginal History Aboriginal History is a refereed journal that presents articles and information in Australian ethnohistory and contact and post-contact history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia, are welcomed. Subjects include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, archival and bibliographic articles, and book reviews. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, Coombs Building (9) ANU, ACT, 0200, or [email protected]. -

Racist Structures and Ideologies Regarding Aboriginal People in Contemporary and Historical Australian Society

Master Thesis In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science: Development and Rural Innovation Racist structures and ideologies regarding Aboriginal people in contemporary and historical Australian society Robin Anne Gravemaker Student number: 951226276130 June 2020 Supervisor: Elisabet Rasch Chair group: Sociology of Development and Change Course code: SDC-80436 Wageningen University & Research i Abstract Severe inequalities remain in Australian society between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people. This research has examined the role of race and racism in historical Victoria and in the contemporary Australian government, using a structuralist, constructivist framework. It was found that historical approaches to governing Aboriginal people were paternalistic and assimilationist. Institutions like the Central Board for the Protection of Aborigines, which terrorised Aboriginal people for over a century, were creating a racist structure fuelled by racist ideologies. Despite continuous activism by Aboriginal people, it took until 1967 for them to get citizens’ rights. That year, Aboriginal affairs were shifted from state jurisdiction to national jurisdiction. Aboriginal people continue to be underrepresented in positions of power and still lack self-determination. The national government of Australia has reproduced historical inequalities since 1967, and racist structures and ideologies remain. ii iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Elisabet Rasch, for her support and constructive criticism. I thank my informants and other friends that I met in Melbourne for talking to me and expanding my mind. Floor, thank you for showing me around in Melbourne and for your never-ending encouragement since then, via phone, postcard or in person. Duane Hamacher helped me tremendously by encouraging me to change the topic of my research and by sharing his own experiences as a researcher. -

Doomed Race’ Assumptions in the Administration of Queensland’S Indigenous Population by the Chief Protectors of Aboriginals from 1897 to 1942

THE IMPACT OF ‘DOOMED RACE’ ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ADMINISTRATION OF QUEENSLAND’S INDIGENOUS POPULATION BY THE CHIEF PROTECTORS OF ABORIGINALS FROM 1897 TO 1942 Robin C. Holland BA (Hons) Class 1, Queensland University of Technology Submitted in full requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) Division of Research and Commercialisation Queensland University of Technology Research Students Centre August 2013 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how the perception of Aborigines becoming a ‘doomed race’ in Australia manifested itself and became embedded in the beliefs of white society during the decades between 1850 and 1870. Social anthropologists who engaged in scientific study and scrutiny of Aboriginal communities contributed to the erroneous belief. Their studies suggested that the physical evolution and ‘retarded development’ of a race with genetic links to ‘Stone Age’ beings could not continue to survive within the advancing culture of the white race. The anthropological determination of Aborigines as a doomed race gained further currency with the scientific understandings supporting white superiority. Consequently, the ‘doomed race’ theory became the dominant paradigm to emerge from previously explored social, anthropological and early settler society. After 1897, the ‘doomed race’ theory, so embedded in the belief system of whites, contributed significantly to the pervasive ideologies that formed the racist, protectionist policies framed by the nation’s Colonial Governments. Even though challenges to the ‘doomed race’ theory appeared in the late 1930s, it continued to be a subterfuge for Australian State and Federal Governments to maintain a paternalistic administration over Australia’s Indigenous population. The parsimony displayed in the allocation of funding and lack of available resources contributed significantly to the slow and methodical destruction of the culture and society of Aborigines. -

Visitor Responses to Palm Island in the 1920S and 1930S1

‘Socialist paradise’ or ‘inhospitable island’? Visitor responses to Palm Island in the 1920s and 1930s1 Toby Martin Tourists visiting Queensland’s Palm Island in the 1920s and 1930s followed a well-beaten path. They were ferried there in a launch, either from a larger passenger ship moored in deeper water, or from Townsville on the mainland. Having made it to the shallows, tourists would be carried ‘pick a back’ by a ‘native’ onto a ‘palm-shaded’ beach. Once on the grassy plains that stood back from the beach, they would be treated to performances such as corroborees, war dances and spear-throwing. They were also shown the efforts of the island’s administration: schools full of happy children, hospitals brimming with bonny babies, brass band performances and neat, tree-fringed streets with European- style gardens. Before being piggy-backed to their launches, the tourist could purchase authentic souvenirs, such as boomerangs and shields. As the ship pulled away from paradise, tourists could gaze back and reflect on this model Aboriginal settlement, its impressive ‘native displays’, its ‘efficient management’ and the ‘noble work’ of its staff and missionaries.2 By the early 1920s, the Palm Island Aboriginal reserve had become a major Queensland tourist destination. It offered tourists – particularly those from the southern states or from overseas – a chance to see Aboriginal people and culture as part of a comfortable day trip. Travellers to and around Australia had taken a keen interest in Aboriginal culture and its artefacts since Captain Cook commented on the ‘rage for curiosities amongst his crew’.3 From the 1880s, missions such as Lake Tyers in Victoria’s Gippsland region had attracted 1 This research was undertaken with the generous support of the State Library of NSW David Scott Mitchell Fellowship, and the ‘Touring the Past: History and Tourism in Australia 1850-2010’ ARC grant, with Richard White. -

Health and Physical Education

Resource Guide Health and Physical Education The information and resources contained in this guide provide a platform for teachers and educators to consider how to effectively embed important ideas around reconciliation, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contributions, within the specific subject/learning area of Health and Physical Education. Please note that this guide is neither prescriptive nor exhaustive, and that users are encouraged to consult with their local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, and critically evaluate resources, in engaging with the material contained in the guide. Page 2: Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 3: Timeline of Key Dates in the more Contemporary History of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 5: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Organisations, Programs and Campaigns Page 6: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Sportspeople Page 8: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Events/Celebrations Page 12: Other Online Guides/Reference Materials Page 14: Reflective Questions for Health and Physical Education Staff and Students Please be aware this guide may contain references to names and works of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that are now deceased. External links may also include names and images of those who are now deceased. Page | 1 Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education “[Health and] healing goes beyond treating…disease. It is about working towards reclaiming a sense of balance and harmony in the physical, psychological, social, cultural and spiritual works of our people, and practicing our profession in a manner that upholds these multiple dimension of Indigenous health” –Professor Helen Milroy, Aboriginal Child Psychiatrist and Australia’s first Aboriginal medical Doctor. -

Walata Tyamateetj a Guide to Government Records About Aboriginal People in Victoria

walata tyamateetj A guide to government records about Aboriginal people in Victoria Public Record Office Victoria and National Archives of Australia With an historical overview by Richard Broome walata tyamateetj means ‘carry knowledge’ in the Gunditjmara language of western Victoria. Published by Public Record Office Victoria and National Archives of Australia PO Box 2100, North Melbourne, Victoria 3051, Australia. © State of Victoria and Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the National Archives of Australia and Public Record Office Victoria. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be directed to the Publishing Manager, National Archives of Australia, PO Box 7425, Canberra Business Centre ACT 2610, Australia, and the Manager, Community Archives, Public Record Office Victoria, PO Box 2100, North Melbourne Vic 3051, Australia. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Victoria. Public Record Office, author. walata tyamateetj: a guide to government records about Aboriginal people in Victoria / Public Record Office Victoria and National Archives of Australia; with an historical overview by Richard Broome. ISBN 9780987283702 (paperback) ISBN 9780987283719 (ebook) Victoria. Public Record Office.–Catalogs. National Archives of Australia. Melbourne Office.–Catalogs. Aboriginal Australians–Victoria–Archives. Aboriginal Australians–Victoria–Bibliography–Catalogs. Public records–Victoria–Bibliography–Catalogs. Archives–Victoria–Catalogs. Victoria–Archival resources. National Archives of Australia. Melbourne Office, author. Broome, Richard, 1948–. 016.99450049915 Public Record Office Victoria contributors: Tsari Anderson, Charlie Farrugia, Sebastian Gurciullo, Andrew Henderson and Kasia Zygmuntowicz. National Archives of Australia contributors: Grace Baliviera, Mark Brennan, Angela McAdam, Hilary Rowell and Margaret Ruhfus. -

Chief Protector of Aborigines

8. Chief Protector of Aborigines Henry Prinsep took up the role of Western Australia’s first Chief Protector of Aborigines anticipating a change from the unrelenting grind of the Mines Department, but soon realised the job would place him in the midst of fraught political battles over the colony’s indigenous populations. His first parliamentary master, Premier John Forrest, had an active interest in the portfolio and wanted the job done as he determined. A self-proclaimed expert on Aboriginal matters, Forrest believed that governments should intervene only in the most extreme cases of mistreatment or poverty. It was his conviction that Aboriginal people were, in any case, disappearing and would have little future in the development of the State. He wanted his new Aborigines Department to stay small and cost little. It was the responsibility of pastoralists and farmers to look after their Aboriginal workforces, and Aboriginal people should be compelled either to work or sustain themselves in their traditional way. Prinsep’s job was to remain in his Perth office and efficiently manage a meagre budget and staff, devoting his efforts to providing rations to a population of dispossessed Aboriginal people that was expanding rapidly as colonisation spread throughout Western Australia. Prinsep’s qualifications for the position of Chief Protector of Aborigines were not immediately evident, even to members of his family. Like many colonists in the country areas of Western Australia, Prinsep had encountered Aboriginal people intermittently as pastoral workers, and had been involved in the humane activities of dispensing rations, clothing and blankets, principally as a member of the church. -

Use of Theses

THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. DISEASE, HEAL TH AND HEALING: aspects of indigenous health in Western Australia and Queensland, 1900-1940 Gordon Briscoe A thesis submitted to History Program, Research School of Social Sciences The Australian National University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 1996 This thesis is all my own work except where otherwise acknowledged Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my late mother, Eileen Briscoe, who gave me my Aboriginal identity, to my wife Norma who kept body and soul together while the thesis was created, developed and nurtured and, finally, to the late Professor Fred Hollows who gave me the inspiration to believe in my~lf and to accept that self-doubt was the road to scholarship. (i) Acknowledgments I have gathered many debts during the development, progress and completion of this thesis. To the supervisory committee of Dr Alan Gray, Dr Leonard R. Smith, Professor F.B. Smith and Professor Donald Denoon, who have all helped me in various ways to bring this task to its conclusion. To Emeritus Professor Ken Inglis who supported me in the topic I chose, and in reading some written work of mine in the planning stages, to Dr Ian Howie-Willis for his textual advice and encouragement and to our family doctor, Dr Tom Gavranic, for his interest in the thesis and for looking after my health. -

Governance in the Early Colony

GOVERNANCE IN THE EARLY COLONY The History Trust of South Australia HISTORY TRUST OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA CENTRE OF DEMOCRACY developed this education resource using The History Trust of South Australia operates The Centre of Democracy is a collaboration the expertise, collections and resources three museums - the Migration Museum, between the History Trust of South Australia of the History Trust of South Australia, the National Motor Museum and the South and the State Library of South Australia. It is its museums and partners. Our learning Australian Maritime Museum, along with supported by the South Australian Government. programs bring to life the stories, the Centre of Democracy managed in Its vibrant program of education, public, objects and people that make up South collaboration with the State Library of South and online programs engage and inform Australia’s rich and vibrant history. Australia. The History Trust’s role is to visitors about the ideas behind democracy, encourage current and future generations political participation and citizenship. The of South Australians to discover this state’s gallery features state treasures from History rich, relevant and fascinating past through Trust and State Library collections, as well as its public programs and museums including items on loan from State Records of South the Migration Museum, the South Australian Australia, the Art Gallery of South Australia, Maritime Museum, the National Motor the Courts Authority, Parliament House, Museum and the Centre of Democracy. Government House and private lenders. history.sa.gov.au centreofdemocracy.sa.gov.au Torrens Parade Ground, Victoria Dr, Adelaide Institute Building, Kintore Ave, Adelaide (08) 8203 9888 (08) 8203 9888 GOVERNANCE IN THE EARLY COLONY AN EDUCATION RESOURCE FOR SECONDARY & SENIOR TEACHERS CONTENTS USING THIS RESOURCE KEY INQUIRY QUESTIONS 02 THE PROVINCE OF This resource is intended to be used in • How have laws affected the lives of SOUTH AUSTRALIA conjunction with three videos produced by people, past and present? the History Trust. -

The Stolen Generations and Genocide: Robert Manne’S in Denial: the Stolen Generations and the Right

The Stolen Generations and genocide: Robert Manne’s In denial: the Stolen Generations and the Right Bain Attwood In recent years many Australians have been troubled over two words or terms, the Sto- len Generations and genocide, and no more so than when they have appeared in tandem, as they did in the report of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Com- mission’s inquiry into the separation of Aboriginal children, Bringing Them Home,1 and the inquiry that gave rise to it.2 Subsequently many conservatives have increased their attacks upon so-called black armband history and particularly the Stolen Generations narrative.3 This assault gathered momentum during 1999 and 2000, eventually provok- ing the political commentator and historian Robert Manne to pen In denial: the Stolen Generations and the Right, an essay in which, to quote the publicists for this new venture in Australian publishing, the Australian Quarterly Essay, he sets out to ‘demolish’ these critics and their ‘demolition’ of the history presented by Bringing Them Home.4 Manne, as he makes abundantly clear throughout In denial, is not only convinced there is ‘a growing atmosphere of right-wing and populist resistance to discussion of historical injustice and the Aborigines’ in Australia today; he also believes there has been ‘an orchestrated campaign’ by a ‘small right-wing intelligentsia’ to ‘change the moral and political balance … with regard to the Aboriginal question as a whole’ and ‘the issue of the Stolen Generations’ in particular. Manne also fears this has been effec- tive, creating ‘scepticism and outright disbelief’ among ‘a highly receptive audience’.5 1. -

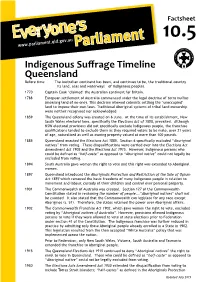

Indigenous Suffrage Timeline

Factsheet 10.5 Indigenous Suffrage Timeline Queensland Before time The Australian continent has been, and continues to be, the traditional country – its land, seas and waterways – of Indigenous peoples. 1770 Captain Cook ‘claimed’ the Australian continent for Britain. 1788 European settlement of Australia commenced under the legal doctrine of terra nullius (meaning land of no-one). This doctrine allowed colonists settling the ‘unoccupied’ land to impose their own laws. Traditional Aboriginal systems of tribal land ownership were neither recognised nor acknowledged. 1859 The Queensland colony was created on 6 June. At the time of its establishment, New South Wales electoral laws, specifically the Elections Act of 1858, prevailed. Although NSW electoral provisions did not specifically exclude Indigenous people, the franchise qualifications tended to exclude them as they required voters to be male, over 21 years of age, naturalised as well as owning property valued at more than 100 pounds. 1885 Queensland enacted the Elections Act 1885. Section 6 specifically excluded “Aboriginal natives” from voting. These disqualifications were carried over into the Elections Act Amendment Act 1905 and the Elections Act 1915. However, Indigenous persons who could be defined as “half-caste” as opposed to “Aboriginal native” could not legally be excluded from voting. 1894 South Australia gave women the right to vote and this right was extended to Aboriginal women. 1897 Queensland introduced the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 which removed the basic freedoms of many Indigenous people in relation to movement and labour, custody of their children and control over personal property. 1901 The Commonwealth of Australia was created. -

A Doctor Across Borders Raphael Cilento and Public Health from Empire to the United Nations

A DOCTOR ACROSS BORDERS RAPHAEL CILENTO AND PUBLIC HEALTH FROM EMPIRE TO THE UNITED NATIONS A DOCTOR ACROSS BORDERS RAPHAEL CILENTO AND PUBLIC HEALTH FROM EMPIRE TO THE UNITED NATIONS ALEXANDER CAMERON-SMITH PACIFIC SERIES Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760462642 ISBN (online): 9781760462659 WorldCat (print): 1088511587 WorldCat (online): 1088511717 DOI: 10.22459/DAB.2019 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover images: Cilento in 1923, John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Neg: 186000. Map of the ‘Austral-Pacific Regional Zone’, Epidemiological Record of the Austral-Pacific Zone for the Year 1928 (Canberra: Government Printer, 1929), State Library of New South Wales, Q614.4906/A. This edition © 2019 ANU Press Contents Abbreviations . vii Map and plates . ix Acknowledgements . xi Introduction . 1 1 . An education in empire: Tropical medicine, Australia and the making of a worldly doctor . 17 2 . A medico of Melanesia: Colonial medicine in New Guinea, 1924–1928 . 51 3 . Coordinating empires: Nationhood, Australian imperialism and international health in the Pacific Islands, 1925–1929 . 93 4 . Colonialism and Indigenous health in Queensland, 1923–1945 . 133 5 . ‘Blueprint for the Health of a Nation’: Cultivating the mind and body of the race, 1929–1945 . 181 6 . Social work and world order: The politics and ideology of social welfare at the United Nations .