Use of Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter April 2012

Newsletter April 2012 President’s Report The first quarter of 2012 has gone very quickly, and been launched for nurses to tell of their experiences. already there has been one Market Day, and one In particular we are interested in stories about the major tour of the Hospital Museum. The Museum experience of living in Nurses’ Quarters, and the ex- tends to increase in popularity each Market Day. periences of student nurses who were the pioneers The first major tour to the Museum occurred in March of the University based system. We are calling for when Members of the University of the Third Age nurses to take time to write to us of their experi- arranged for their routine monthly outing to be a guid- ences. These stories after editing will be collated into ed tour through the Museum. U3A Members met at a book to be launched at next year’s IND Celebra- Arnolds, and while enjoying morning tea, Yvonne gave tions. Some examples of such stories will be available a much appreciated overview of the Museum’s origins. for reading at the IND Function. Morning tea was followed by guided tours through the Information concerning the program for International Museum and its archive area. Nurses’ Day is on a small flyer included with this As part of the Committee’s endeavours to make each newsletter. Please send anecdotal stories to ACHHA, repeat visit by the public to the Museum of continued PO Box 4035, Rockhampton Qld 4700 or email to interest and in keeping with the strategic plan, pro- [email protected]. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Newsletter December 2011

Newsletter December 2011 President’s Report Elections for the positions on the ACHHA Manage- be an invitation for nurses to write short anecdotal ment committee were held in October, and the new stories of experiences they may have had with re- committee structure can be found elsewhere in this gards hospital training or experiences of living in newsletter. My congratulations and welcome to Nurses’ Quarters. Relevant stories will appear in members of the new committee. this Newsletter, and copies will be kept at the Mu- seum. I continue as President, and I thank members for again electing me for a further year. It is more School tours continued through out this quarter, fulfilling if belonging to an organisation, to be in- guided by members of the committee. There is a volved in the overall management, and I appreciate need for more volunteers to help on these days, as this ongoing opportunity afforded me. the groups can be large, and at least three people are needed for the guiding. Please let me, or anoth- Through personal and work commitments, Debbie er member know if able to assist. has elected not to seek nomination again this year. I thank Debbie for her input over the past years, and The favourable and enthusiastic Comments in our welcome her offer to continue in the role of Cura- Visitors Book indicate that the Hospital Museum is tor, and to continue working on the school tour pro- more than appreciated by the Visitors, and adds to ject. With Debbie and Lorraine as Curators and the satisfaction of all that are involved in its Yvonne as Archivist, the collection is in safe hands. -

Did You Know? Some Quick Statistics…

Football, or soccer, is truly a World Game, with an unmatched ability to bring people from different backgrounds together. With attention turning to Brazil for the FIFA World Cup, which starts on 12 June 2014, there is no better time to discover the contributions Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have made to the World Game. Did you know? Harry Williams is the only male Aboriginal player to represent Australia at a World Cup. He joined the Socceroos in 1970 and later played in the 1974 World Cup in Germany.1 In 2008, Jade North became the first Aboriginal player to captain the Socceroos. He has a tattoo with his tribal name, “Biripi”, on his left arm and recently played in the 2014 A-league grand final.2 Lydia Williams and Kyah Simon are the first two Aboriginal women to play together in a World Cup. Lydia played in the 2007 and 2011 World Cups, and Kyah played in 2011.3 In 2011 Kyah became the first Aboriginal Australian to score a goal in a World Cup. Charlie Perkins was offered a contract to play soccer for Manchester United before becoming the first Aboriginal person to graduate from the University of Sydney. Travis Dodd was the first Aboriginal Australian to score a goal for the Socceroos.4 Some quick statistics… The Football Federation of Australia (FFA) estimates that there are 2,600 registered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander soccer players.5 Harry Williams played 6 matches for Australia in the 1974 World Cup qualifying campaign.6 1 http://www.deadlyvibe.com.au/2007/11/harry-williams/ 2 The Aboriginal Soccer Tribe: A History of Aboriginal Involvement with the World Game, John Maynard, Magabala Books: Broome, 2011 3 http://noapologiesrequired.com/the-matildas/15-facts-about-the-matildas 4 http://www.footballaustralia.com.au/perthglory/players/Travis-Dodd/72 5 http://www.footballaustralia.com.au/site/_content/document/00000601-source.pdf 6 Tatz, C & Tatz, C. -

Address-In-Reply 6 Sep 2018

2380 Address-in-Reply 6 Sep 2018 this consultation draft now so that the parliament, the waste and recycling industry, councils and the community can consider the full package of proposed amendments to legislation to implement the waste levy. Information about consultation will be provided on the Department of Environment and Science’s website. Since March this year, when the government announced our intention to accept the recommendation of the Lyons report and introduce a waste levy to underpin our waste strategy, we have been undertaking comprehensive consultation with a range of stakeholders to ensure we hear everyone’s voices. I look forward to continuing consultation as the bill progresses through parliament, and as the regulations are discussed. Queenslanders are increasingly conscious of waste as an economic and environmental issue. This bill delivers a key enabler of change. The waste levy will provide an incentive for people to reduce the waste they create and find more productive and job-creating uses for their waste. Importantly, the bill also ensures that it will not cost Queenslanders any more to put out their wheelie bin. It is not hard to see the long-term economic and environmental benefits that this levy will bring to Queensland. Through the introduction of a waste levy and a new waste strategy, we can work towards a more sustainable future for generations of Queenslanders to come. I commend the bill to the House. First Reading Hon. LM ENOCH (Algester—ALP) (Minister for Environment and the Great Barrier Reef, Minister for Science and Minister for the Arts) (11.29 am): I move— That the bill be now read a first time. -

Colonial Australia and Aboriginal Resistance

www.galaxyimrj.com Galaxy: International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ISSN 2278-9529 “The Frontier Spectrum”: Colonial Australia and Aboriginal Resistance Prasenjit Das Ph.D. Scholar Dept. of English, Ranchi University, Jharkhand, India You are the New Australians, but we are the Old Australians. We have in our arteries the blood of the original Australians, who have lived in this land for many thousands of years.—Argus as qtd. in Bourke et al 43. ...I see Indigenous peoples as having twin projects: at one level, we must understand the motivation behind the historical constructions of Aboriginality, and understand why they have had such a grip over colonizing populations; simultaneously we must continuously subvert the hegemony over our own representations, and allow our visions to create the world of meaning in which we relate to ourselves, to each other and to non-Indigenous peoples.—Dodson 33. Australian nation is predominantly ‘White’ not only in terms of society and culture, but also when viewed in the perspectives of literature, art and identity in general. There is even a claim of a ‘White Australian Nation’, from the very time when the European explorers said to have ‘discovered’ an island in the southern hemisphere, dismissed as terra nullius1, to the present day first-world capitalist situation. This was primarily achieved through a complete negation of Aboriginal existence, an utter disregard of Aboriginal identity—history, tradition, culture values, customs and mores of living. Epithets such as ‘blood thirsty’, ‘cunning’ ‘primitive’, ‘non- modern’ ‘Australian Nigger’ were often used to label and denote the Aboriginals by the colonizers. This ‘othering’ was evident in certain lopsided observations of the white colonizers: ...degraded as to divine things, almost on a level with a brute.. -

My Mother Found Me in Alice Springs

THE FIRST ABORIGINAL DOCTOR Gordon Briscoe 19 April 2019 Born in Alice Springs in 1938 Gordon Briscoe was a talented soccer player and became the first Indigenous person to gain a PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) from an Australian University in 1997. Gordon Briscoe in the 1960s. Doctor Briscoe’s journey is remarkable. Since the 1950s he has been a prominent Indigenous activist, leader, researcher, writer, teacher and public commentator. After a challenging institutional upbringing which saw him criss-cross the nation, initially struggling at school with limited support, he managed to gain the highest qualification an Australian University can offer. Along the way he was the first Indigenous person to stand for Federal Parliament in 1972 and worked with legendary eye surgeon Fred Hollows to establish the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program. Today he is one of the leading academics specialising in Indigenous history and his research has helped him to reclaim his traditional family and sense of cultural identity. Descended from the Marduntjara and Pitjantjatjara peoples of Central Australia Briscoe’s maternal grandmother, Kanaki, was born west of Kulkara. She travelled around the Mardu lands to forage and participate in ceremonies. Kanaki’s traditional husband was Wati Kunmanara, but she conceived Briscoe’s mother Eileen with a white man named Billy Briscoe. Briscoe lived at “The Bungalow” in Alice Springs until he was four. After the bombing of Darwin in February 1942, the residents of the Aboriginal institutions were evacuated from the Northern Territory. Briscoe and his mother were initially evacuated to Mulgoa in the Blue Mountains of NSW, but after the birth of his brother they were sent to the South Australian town of Balaklava for the remainder of the war. -

How to Write a Good Letter to the Editor: QLD a Guide to Writing Awesome, Powerful Letters

How to write a good letter to the editor: QLD A Guide to writing awesome, powerful letters Letters to the editor of local papers are an excellent way for politicians to gauge what the public is thinking. This is a how-to guide for writing powerful and useful letters that can inform the public debate around Adani’s coal project. What makes a good letter? Some tips: ● The best letters are short, snappy and succinct - never longer than 200 words. ● Try to limit your letter to one central idea so it is clear and easy to read. Don’t be afraid to use humour if it suits! ● Good letters are timely if they are in response to a big announcement or event. This means written and sent on the same day. ● Back-up your claims with facts where appropriate. There are many resources on our website (see below for links). ● Try to weave in a personal story if you can and it is fitting. For example: ○ I’m a tourist operator on the Reef and Adani’s coal mine will put my business in jeopardy. ○ I am a teacher and see school students are very attuned to the impact of climate change on the Reef and Adani’s role in this. ○ I went to visit the Reef last year and am saddened by the fact the QLD Government is ignoring coral bleaching events in favour of more coal mining. ○ I’m a Townsville resident who has experienced the mining industry’s boom-bust cycles and I think the future of Townsville should be solar. -

Health and Physical Education

Resource Guide Health and Physical Education The information and resources contained in this guide provide a platform for teachers and educators to consider how to effectively embed important ideas around reconciliation, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories, cultures and contributions, within the specific subject/learning area of Health and Physical Education. Please note that this guide is neither prescriptive nor exhaustive, and that users are encouraged to consult with their local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, and critically evaluate resources, in engaging with the material contained in the guide. Page 2: Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 3: Timeline of Key Dates in the more Contemporary History of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Page 5: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Organisations, Programs and Campaigns Page 6: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Sportspeople Page 8: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education Events/Celebrations Page 12: Other Online Guides/Reference Materials Page 14: Reflective Questions for Health and Physical Education Staff and Students Please be aware this guide may contain references to names and works of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that are now deceased. External links may also include names and images of those who are now deceased. Page | 1 Background and Introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Physical Education “[Health and] healing goes beyond treating…disease. It is about working towards reclaiming a sense of balance and harmony in the physical, psychological, social, cultural and spiritual works of our people, and practicing our profession in a manner that upholds these multiple dimension of Indigenous health” –Professor Helen Milroy, Aboriginal Child Psychiatrist and Australia’s first Aboriginal medical Doctor. -

Highways Byways

Highways AND Byways THE ORIGIN OF TOWNSVILLE STREET NAMES Compiled by John Mathew Townsville Library Service 1995 Revised edition 2008 Acknowledgements Australian War Memorial John Oxley Library Queensland Archives Lands Department James Cook University Library Family History Library Townsville City Council, Planning and Development Services Front Cover Photograph Queensland 1897. Flinders Street Townsville Local History Collection, Citilibraries Townsville Copyright Townsville Library Service 2008 ISBN 0 9578987 54 Page 2 Introduction How many visitors to our City have seen a street sign bearing their family name and wondered who the street was named after? How many students have come to the Library seeking the origin of their street or suburb name? We at the Townsville Library Service were not always able to find the answers and so the idea for Highways and Byways was born. Mr. John Mathew, local historian, retired Town Planner and long time Library supporter, was pressed into service to carry out the research. Since 1988 he has been steadily following leads, discarding red herrings and confirming how our streets got their names. Some remain a mystery and we would love to hear from anyone who has information to share. Where did your street get its name? Originally streets were named by the Council to honour a public figure. As the City grew, street names were and are proposed by developers, checked for duplication and approved by Department of Planning and Development Services. Many suburbs have a theme. For example the City and North Ward areas celebrate famous explorers. The streets of Hyde Park and part of Gulliver are named after London streets and English cities and counties. -

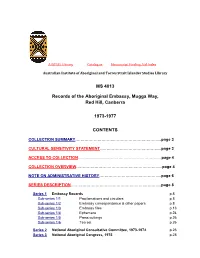

MS 4013 Records of the Aboriginal Embassy, Mugga Way, Red Hill

AIATSIS Library Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid Index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 4013 Records of the Aboriginal Embassy, Mugga Way, Red Hill, Canberra 1973-1977 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY………………………..……………………….……....page 3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT……………….…………………….....page 3 ACCESS TO COLLECTION…………………………….…………………………page 4 COLLECTION OVERVIEW…………………………………….….…………….....page 4 NOTE ON ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY………………………………………...page 6 SERIES DESCRIPTION……………………………………….…………………...page 8 Series 1 Embassy Records p.8 Sub-series 1/1 Proclamations and circulars p.8 Sub-series 1/2 Embassy correspondence & other papers p.8 Sub-series 1/3 Embassy files p.13 Sub-series 1/4 Ephemera p.24 Sub-series 1/5 Press cuttings p.26 Sub-series 1/6 Tea set p.26 Series 2 National Aboriginal Consultative Committee, 1973-1974 p.26 Series 3 National Aboriginal Congress, 1975 p.28 MS 4013, Records of the Aboriginal Embassy, Mugga Way, Red Hill, Canberra Series 4 Commonwealth Parliament, Records of Committees of Inquiry p.28 Sub-series 4/1 House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs p.28 Sub-series 4/2 Senate Committees p.31 Series 5 Reports p.41 Series 6 Copies of journal articles p.44 Series 7 Legislation p.48 Series 8 Printed material: Maori; Canadian Indian; African, Israeli & others p.50 Series 9 Poster p.54 Appendix: discarded printed material Publications – Annual Reports p.55 Publications – Other Reports p.57 Publications – Submissions to Committees of Inquiry p.60 Publications – Other -

2021-22 Accreditation Terms and Conditions Please Note: the Part A

2021-22 Accreditation Terms and Conditions Please note: The Part A – General Terms apply to all applicants (excluding signatories to the Code of Practice of Sports News Reporting). The Part B – Code Terms apply to representatives of signatories to the Code of Practice of Sports News Reporting (see page 8). The signatories are as follows: 1. Agence France-Presse (AFP) 2. APN News & Media 3. Associated Press 4. Australian Assoc. Press 5. Fairfax Media (SMH, Age, Fin Review, Brisbane Times) 6. Getty Images 7. News International (Sun, Sunday Times, The Times, News of the World) 8. News Corp (The Australian, The Daily Telegraph, The Courier Mail, Herald Sun, The Advertiser, The Mercury, Townsville Bulletin, NT News, Daily Mercury, The Observer, The Morning Bulletin, Fraser Coast Chronicle, News - Mail, Gympie Times, Sunshine Coast Daily, Queensland Times, The Chronicle, Warwick Daily News, Northern Star, Daily Examiner) 9. Perform 10. The Daily Mail 11. The Daily Telegraph 12. The Guardian 13. The Independent 14. The Independent on Sunday 15. The Observer 16. The Sunday Telegraph 17. WA Newspapers Limited (The West Australian and The Sunday Times) 18. Thomson Reuters (i.e. English Regionals) 2021-22 Accreditation Terms and Conditions PART A – General Terms (e) not breach the intellectual property rights of any person involved in the staging of a Match; Accreditation – Venue Access (f) not at any time permit, encourage or allow any Cricket Australia (CA) is a not-for-profit body with person under the age of eighteen (18) to enter into any responsibility for the development of the game of cricket media facility areas at the Venue without the prior written in Australia.