Encouraging Parent Involvement at Home Through Improved Home-School Connections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hirsh-Pasek Vita 2-21

Date: February, 2021 Kathryn A. Hirsh-Pasek, Ph.D. The Debra and Stanley Lefkowitz Distinguished Faculty Fellow Senior Fellow Brookings Institution Academic Address Department of Psychology Temple University Philadelphia, PA 19122 (215) 204-5243 [email protected] twitter: KathyandRo1 Education University of Pennsylvania, Ph.D., 1981 (Human Development/Psycholinguistics) University of Pittsburgh, B.S., 1975 (Psychology/Music) Manchester College at Oxford University, Non-degree, 1973-74 (Psychology/Music) Honors and Awards Placemaking Winner, the Real Play City Challenge, Playful Learning Landscapes, November 2020 AERA Fellow, April 2020 SIMMS/Mann Whole Child Award, October 2019 Fellow of the Cognitive Science Society, December 2018 IDEO Award for Innovation in Early Childhood Education, June 2018 Outstanding Public Communication for Education Research Award, AERA, 2018 Living Now Book Awards, Bronze Medal for Becoming Brilliant, 2017 Society for Research in Child Development Distinguished Scientific Contributions to Child Development Award, 2017 President, International Congress on Infant Studies, 2016-2018 APS James McKeen Cattell Fellow Award - “a lifetime of outstanding contributions to applied psychological research” – 2015 Distinguished Scientific Lecturer 2015- Annual award given by the Science Directorate program of the American Psychological Association, for three research scientists to speak at regional psychological association meetings. President, International Congress on Infant Studies – 2014-2016 NCECDTL Research to Practice Consortium Member 2016-present Academy of Education, Arts and Sciences Bammy Award Top 5 Finalist “Best Education Professor,” 2013 Bronfenbrenner Award for Lifetime Contribution to Developmental Psychology in the service of science and society. August 2011 Featured in Chronicle of Higher Education (February 20, 2011): The Case for play. Featured in the New York Times (January 5, 2011) Effort to Restore Children’s Play Gains Momentum (article on play and the Ultimate Block Party; most emailed article of the day). -

Vtech/Leapfrog Consumer Research

VTech/LeapFrog consumer research Summary report Prepared For: Competition & Markets Authority October 2016 James Hinde Research Director Rebecca Harris Senior Research Manager 3 Pavilion Lane, Strines, Stockport, Cheshire, SK6 7GH +44 (0)1663 767 857 Page 1 djsresearch.co.uk Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 3 Background & Methodology ........................................................................................... 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 Research Objectives .................................................................................................. 5 Sample .................................................................................................................... 6 Methodology ............................................................................................................. 7 Reporting ............................................................................................................... 10 Profile of participants .................................................................................................. 11 Purchase context, motivations and process ................................................................... 24 Diversion behaviour ................................................................................................... -

Senior Newsletter September 2017

T HE S ENIORS CENE Programs and Activities for Older Adults Programas y Actividades para Adultos Mayores Offered by: Division of Senior Services SEPTEMBER http://www.santafenm.gov/senior_scene_newsletter 2017 CITY OF SANTA FE, DIVISION OF SENIOR SERVICES Administration Offices 1121 Alto Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 SEPTEMBER - 2017 The City of Santa Fe Division of Senior Services offers a variety of programs and services at five senior centers throughout Santa Fe. If you are age 60 or over, we invite you to utilize our facilities and participate in the various programs and activities that are available, most of which are free (some do request a small donation). Read through the activities section for more information about ongoing and current activities. These facilities and services are here for you – we encourage you to stop by and use them, and we look forward to meeting you! The Senior Scene newsletter is a free monthly publication designed to help you navigate our services and learn about upcoming events. You will find sections on community news, senior center activities and menus, volunteer programs, 50+ Senior Olympics, health, safety, legal and consumer issues, as well as word puzzles to sharpen the mind. The newsletter is available at all City of Santa Fe senior centers, fitness facilities, and public libraries, as well as various senior living communities and healthcare agencies. It is also available online at www.santafenm.gov, simply type “Senior Scene” in the keyword search box at the top then click the purple underlined words “Senior Scene Newsletter.” Front Desk Reception (505) 955-4721 In Home Support Services: Respite Care, Toll-Free Administration Line (866) 824-8714 Homemaker Gino Rinaldi, DSS Director 955-4710 Theresa Trujillo, Program Supervisor 955-4745 Katie Ortiz, Clerk Typist 955-4746 Administration Cristy Montoya, Administrative Secretary 955-4721 Foster Grandparent/Senior Companion Program Sadie Marquez, Receptionist 955-4741 Melanie Montoya, Volunteer Prog. -

The Role of Play and Direct Instruction in Problem Solving in 3 to 5 Year Olds

THE ROLE OF PLAY AND DIRECT INSTRUCTION IN PROBLEM SOLVING IN 3 TO 5 YEAR OLDS Beverly Ann Keizer B. Ed. , University of British Columbia, 1971 1 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (EDUCATION) in the Faculty of Education @Beverly Ann Keizer 1983 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY March 1983 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author APPROVAL Name : Beverly Ann Keizer Degree : Master of Arts (Education) Title of Thesis: The Role of Play and Direct Instruction in Problem Solving in 3 to 5 Year Olds Examining Committee Chairman : Jack Martin Roger Gehlbach Senior Supervisor Ronald W. Marx Associate Professor Mary Janice partridge Research Evaluator Management of Change Research Project Children's Hospital Vancouver, B. C. External Examiner Date approved March 14, 1983 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University L ibrary, and to make part ial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

For Christmas I'd Like Betty Aldrich Iowa State College

Volume 23 Article 5 Number 5 The Iowa Homemaker vol.23, no.5 1943 For Christmas I'd Like Betty Aldrich Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/homemaker Part of the Home Economics Commons Recommended Citation Aldrich, Betty (1943) "For Christmas I'd Like," The Iowa Homemaker: Vol. 23 : No. 5 , Article 5. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/homemaker/vol23/iss5/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oI wa Homemaker by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Betty Aldrich describe bring holiday sparkle f, ICKY will usher in the holiday sea low-heeled comfortable shoes the most V son with a flattering wardrobe in popular. But for dress, the opera pump spite of the curtailment of her wartime is still the hit of the coupon No. 18 era clothes budget. Christmas presents and would be an ideal Christmas pres which add to Vicky's wardrobe will be ent. especially welaome this year-particu Gone are the days when Vicky bought larly if they are convertible clothes which the first thing that looked pretty, re can be the foundation of numerous gardless of quality. A duration sensation smart, though inexpensive outfits. in her wardrobe is a dress of flame cash Vicky would be happy to find a dou mere wool. Its dash is carried out in such ble-purpose wool suit under the tree details as the buttoned patch pockets and Christmas morning. -

Jul Aug 2016 Newsletter WEB VERSION

JUL/AUG 2016 Bereaved Parents of the USA Anne Arundel County Chapter COPYRIGHT © 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Our Children Remembered With you went so much of me… Eric Eugene Maier 8/8/1961 - 7/5/1984 “For our wonderful son” Tria Marie Castiglia 7/6/1963 - 10/14/1984 In memory of our dear Tria. Love forever, Dad, Mom and sister Carla. We miss her every day and one day we will be together forever. JUL/AUG 2016 Healing with my Hands In September of 2010 my 25 year old son went into the hospital with a flare up of the Crohn's disease that had been interfering with his life for over 12 years. We expected a 3-4 day stay which was his norm. After a few days of fluids and steroids he would be on his way to a quick recovery. What really happened is that he barely made it home after 2 1/2 months of intensive care and rehab, multiple surgeries, dozens of procedures, a weight loss of 50 pounds and the loss of the life he knew. For this Mama it was the most frightening, agonizing, and heartbreaking time of her life. I plummeted into a dark abyss of which I had never experienced before. Fear and anxiety plagued my every waking moment. Without the aid of a sleeping pill, it also visited me in my sleep. When Tommy died suddenly in March of 2011, I fell even deeper into the abyss. I cared not for surviving and thought endlessly of joining him. Along with my intense need to see him again, my heart and soul needed a respite from the excruciating heartbreak. -

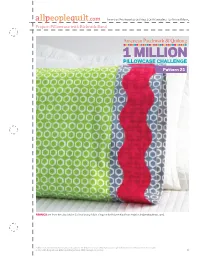

Pillowcase with Rickrack Band Pattern 21

American Patchwork & Quilting | Quilt Sampler | Quilts and More Project: Pillowcase with Rickrack Band Pattern 21 FABRICS are from the Stockholm Collection by Robin Zingone for Robert Kaufman Fabrics (robertkaufman.com). Patt ern may be downloaded for personal use only. No electronic or printed reproduction permitt ed without the prior writt en consent of Meredith Corporation. ©Meredith Corporation 2012. All rights reserved. 1 American Patchwork & Quilting | Quilt Sampler | Quilts and More Project: Pillowcase with Rickrack Band Materials To cut out rickrack appliqués with Assemble Band For one pillowcase: scissors, complete the following 1. Sew together appliquéd and 1 • ⁄4 yard of appliqué print steps. remaining secondary print 6×41" (rickrack appliqués) strips along a pair of long edges 1 • ⁄ 2 yard secondary print 1. The Rickrack Pattern is in (Band Assembly Diagram). (pillowcase band) three parts on pages 4–6. Cut 7 • ⁄8 yard main print (pillowcase out pieces and tape together 2. Join short edges of Step 1 unit body) to make a full pattern before to make a loop. Press seam • Lightweight fusible web tracing. Place fusible web, paper open. Fold loop in half with • Tear-away stabilizer side up, over pattern. Use a wrong side inside; press to make • AccuQuilt Go! Fabric cutter pencil to trace pattern twice, pillowcase band. The band unit 1 1 (optional) leaving ⁄ 2" between tracings. should be 5 ⁄ 2×20" including • AccuQuilt Go! Rickrack Die Cut out drawn shapes roughly seam allowances. 1 #55056 (optional) ⁄4" outside drawn lines. Assemble Pillowcase Finished pillowcase: 30×20" 2. Following manufacturer’s 1. Fold body print 26×41" (fits a standard-size bed pillow) instructions, press fusible-web rectangle in half crosswise to 1 shapes onto wrong side of form a 26×20 ⁄ 2" rectangle. -

SEWING MACHINE MACHINE a CO UDRE MAQUINA DE COSER I Illlllllll Ill Illlllllllllll I MODELS 385

OWNER'S MANUAL MANUEL D'INSTR UCTIONS MANUALDE INSTRUCCIONES SEWING MACHINE MACHINE A CO UDRE MAQUINA DE COSER I Illlllllll Ill Illlllllllllll I MODELS 385. 17026 MODELES MODELOS 385, 17828 SEARS, ROEBUCK AND CO. Dear Customer: You have iust invested in a very fine zigzag sewing machine. Before using your new Kenmore machine, please pause tor a moment and carelully read this booklet which contains instructions on how to operate and care tot your machine. Specific instructions are given on threading, tension adjustments, cleaning, oiling, etc. This wiI] help you obtain the best sewing results and avoid unnecessary service expense tot conditions beyond our control. Advice on the operation and care ot your machine is afways available at your nearest Sears Retal] Store. Please remember, if you have questions about your machine or need parts and service, always mention the model number and serial number when you inquire. Kenmore Sewing Machine Record in space provided below the model number and serial number of this appliance. The model number and serial number are located on the nomenclature plate, as identified on Page 4 of this book]eL Model No. 385. Senal No. Retain these numbers for future reference. THIS MODEL IS A CENTER NEEDLE, LOW BAR SEWING MACHINE. IMPORTANT SAFETY 4. Never operate the sewing machine with any air opening blocked. Keep ventilation openings of the sewing machine and toot controller tree trom accumulation INSTRUCTIONS of lint, dust, and loose cloth. 5. Never drop or insert any obiect into any opening, Your sewing machine is designed and constructed only for HOUSEHOLD use. -

Stem/Steam Formula for Success

STEM/STEAM FORMULA FOR SUCCESS The Toy Association STEM/STEAM Formula for Succcess 1 INTRODUCTION In 2017, The Toy Association began to explore two areas of strong member interest: • What is STEM/STEAM and how does it relate to toys? • What makes a good STEM/STEAM toy? PHASE I of this effort tapped into STEM experts and focused on the meaning and messages surrounding STEM and STEAM. To research this segment, The Toy Association reached out to experts from scientific laboratories, research facilities, professional associations, and academic environments. Insights from these thought leaders, who were trailblazers in their respective field of science, technology, engineering, and/or math, inspired a report detailing the concepts of STEM and STEAM (which adds the “A” for art) and how they relate to toys and play. Toys are ideally suited to developing not only the specific skills of science, technology, engineering, and math, but also inspiring children to connect to their artistic and creative abilities. The report, entitled “Decoding STEM/STEAM” can be downloaded at www.toyassociation.org. In PHASE 2 of this effort, The Toy Association set out to define the key unifying characteristics of STEM/STEAM toys. Before diving into the characteristics of STEM/STEAM toys, we wanted to take the pulse of their primary purchaser—parents of young children. The “Parents’ Report Card,” is a look inside the hopes, fears, frustrations, and aspirations parents have surrounding STEM careers and STEM/STEAM toys. Lastly, we turned to those who have dedicated their careers to creating toys by tapping into the expertise of Toy Association members. -

Apparel Performance Specifications March 2011

APPAREL PERFORMANCE SPECIFICATIONS MARCH 2011 APPAREL PERFORMANCE SPECIFICATIONS NPS -1 All Children’s Apparel All Children’s Apparel NPS - 2 Knit Apparel Children’s Apparel Knit Sleepwear NPS - 3 Knit Apparel Fine Gauge - Natural Fibers NPS - 4 Knit Apparel Fine Gauge - Wool, Silk NPS - 5 Knit Apparel Fine Gauge - Man - made Fibers NPS - 6 Knit Apparel Sweaters - Man-made Fibers NPS - 7 Knit Apparel Sweaters - Natural Fibers NPS - 8 Knit Apparel Swimwear NPS - 12 Woven Apparel Children’s Woven Sleepwear NPS - 13 Woven Apparel Indigo, Sulfur Dyed, Denim and Chambray NPS - 14 Woven Apparel Silk NPS - 15 Woven Apparel Stretch Woven NPS - 16 Woven Apparel Wool and Specialty Fibers NPS - 17 Woven Apparel Terry Cloth/Velour NPS - 18 Woven Apparel Water Repellent Woven’s NPS - 19 Woven Apparel Man-made Fibers NPS - 20 Woven Apparel Natural Fibers NPS - 21 Woven Apparel Swimwear NPS - 22 Woven Apparel Synthetic Lining Fabrics NPS - 24 Leather and Suede Leather and Suede NPS - 25 Trims & Findings For all adult apparel NPG Supplier Procedures Manual © 2011 Nordstrom, Inc., all rights reserved. CONFIDENTIAL: These documents contain proprietary, trade secret, and confidential information which are the property of Nordstrom, Inc. These documents and their contents may not be duplicated or disclosed to any other party without express authorization of Nordstrom, Inc. Page 1 of 23 APPAREL PERFORMANCE SPECIFICATIONS MARCH 2011 KNIT PRODUCT SPECIFICATIONS The Knit Product Specifications are divided by Fiber Content and Fabrication. The following chart gives some examples of which Nordstrom Product Specification (NPS) to use for some of the more common fabrications. The colorfastness level indicated as “Special” indicates a raised surface or special treatment that affects the colorfastness properties differently than a plain surface. -

ED 043 305 PUP DATE Enrs PRICE DOCUMENT RESUME

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 043 305 HE 001 /76 TTTLr The Trustee; A Key to Progress in the Small College. TNSTITUTION Council for the Advancement of Small Colleges, Vashinaton, D.C. PUP DATE [101 NOTE 164p.: Papers presented at an Institute for trustees and administrators of small colleges, Michigan State nniversity, Fast Lansina, Michigan, August, 196c' EnRs PRICE FDES Price 4F-$0.15 FC-5B.30 OESCRIPTORS *Administrator Role, College Administration, Educational Finance, Governance, *Governing aoards, *Nigher Fducation, Leadership Responsibility, Planning, *Ic.sponsibilltv, *Trustees IOSTRACT The primary pw:pose of the institute was to give members (IC the board of trustees of small colleges a better understanding of their proper roles and functions. The emphasis was on increasing the effectiveness of the trustee, both in his general relationship to the college and in his working and policy-formulating relationship to the president and other top-level cdministralors. This boo}- presents the rapers delivered during the week -long program: "College Trusteeship, 1069," by Myron F. Wicket "Oporational Imperatives for a College Poari of Trustees in the 1910s," by Arthur C. rrantzreb; "A Trustee Examines "is Role," by warren M. "uff; "The College and university Student Today," by Richall F. Gross; "The College Student Today," by Eldon Nonnamaker; "Today's l'aculty Member,'' by Peter °prevail; "The Changing Corricilum: Implications for the Small College," by G. tester Pnderson; "How to get the 'lowly," by Gordon 1. Caswell; "Founflations and the Support of ?nigher rduPation," by Manning M.Pattillo; "The Trustee and Fiscal Develorment," by 0ohn R. Haines; "tong-Range Plannina: An Fs.ential in College Administration," by Chester M.Alter; and "Trustee-Presidential Relationships," by Roger J. -

A Strategic Audit of Oriental Trading Company Isaac Coleman University of Nebraska - Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln Honors Program Spring 2019 A Strategic Audit of Oriental Trading Company Isaac Coleman University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses Part of the Business Commons Coleman, Isaac, "A Strategic Audit of Oriental Trading Company" (2019). Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 150. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/honorstheses/150 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses, University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A STRATEGIC AUDIT OF ORIENTAL TRADING COMPANY An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of University Honors Program Requirements University of Nebraska-Lincoln By Isaac Coleman Computer Science College of Arts and Sciences April 7, 2019 Faculty Mentor: Samuel Nelson, Ph.D., Center for Entrepreneurship ABSTRACT Oriental Trading Company is a direct marketer and seller of toys, novelties, wedding favors, custom apparel, and other event supplies. Its products are sold by five brands, each of which participates in a different market. Though its flagship brand, Oriental Trading, is a powerful market leader in novelties and is doing extremely well, the four most recent brands each face distinct challenges and have low name recognition. To increase name recognition and direct sales of these brands, this audit proposes that OTC revitalize its social media presence, add a blog to all of its websites, and resume public participation in local events.