America the Beautiful Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

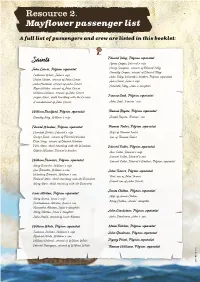

Resource 2 Mayflower Passenger List

Resource 2. Mayflower passenger list A full list of passengers and crew are listed in this booklet: Edward Tilley, Pilgrim separatist Saints Agnus Cooper, Edward’s wife John Carver, Pilgrim separatist Henry Sampson, servant of Edward Tilley Humility Cooper, servant of Edward Tilley Catherine White, John’s wife John Tilley, Edwards’s brother, Pilgrim separatist Desire Minter, servant of John Carver Joan Hurst, John’s wife John Howland, servant of John Carver Elizabeth Tilley, John’s daughter Roger Wilder, servant of John Carver William Latham, servant of John Carver Jasper More, child travelling with the Carvers Francis Cook, Pilgrim separatist A maidservant of John Carver John Cook, Francis’ son William Bradford, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Rogers, Pilgrim separatist Dorothy May, William’s wife Joseph Rogers, Thomas’ son Edward Winslow, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Tinker, Pilgrim separatist Elizabeth Barker, Edward’s wife Wife of Thomas Tinker George Soule, servant of Edward Winslow Son of Thomas Tinker Elias Story, servant of Edward Winslow Ellen More, child travelling with the Winslows Edward Fuller, Pilgrim separatist Gilbert Winslow, Edward’s brother Ann Fuller, Edward’s wife Samuel Fuller, Edward’s son William Brewster, Pilgrim separatist Samuel Fuller, Edward’s Brother, Pilgrim separatist Mary Brewster, William’s wife Love Brewster, William’s son John Turner, Pilgrim separatist Wrestling Brewster, William’s son First son of John Turner Richard More, child travelling with the Brewsters Second son of John Turner Mary More, child travelling -

Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds

Defining the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for The Nanjemoy and Mattawoman Creek Watersheds Prepared By: Scott M. Strickland Virginia R. Busby Julia A. King With Contributions From: Francis Gray • Diana Harley • Mervin Savoy • Piscataway Conoy Tribe of Maryland Mark Tayac • Piscataway Indian Nation Joan Watson • Piscataway Conoy Confederacy and Subtribes Rico Newman • Barry Wilson • Choptico Band of Piscataway Indians Hope Butler • Cedarville Band of Piscataway Indians Prepared For: The National Park Service Chesapeake Bay Annapolis, Maryland St. Mary’s College of Maryland St. Mary’s City, Maryland November 2015 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The purpose of this project was to identify and represent the Indigenous Cultural Landscape for the Nanjemoy and Mattawoman creek watersheds on the north shore of the Potomac River in Charles and Prince George’s counties, Maryland. The project was undertaken as an initiative of the National Park Service Chesapeake Bay office, which supports and manages the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. One of the goals of the Captain John Smith Trail is to interpret Native life in the Middle Atlantic in the early years of colonization by Europeans. The Indigenous Cultural Landscape (ICL) concept, developed as an important tool for identifying Native landscapes, has been incorporated into the Smith Trail’s Comprehensive Management Plan in an effort to identify Native communities along the trail as they existed in the early17th century and as they exist today. Identifying ICLs along the Smith Trail serves land and cultural conservation, education, historic preservation, and economic development goals. Identifying ICLs empowers descendant indigenous communities to participate fully in achieving these goals. -

Girls on the Mayflower

Girls on the Mayflower http://members.aol.com/calebj/girls.html (out of circulation; see: https://www.prettytough.com/girls-on-the-mayflower/ http://mayflowerhistory.com/girls https://itchyfish.com/oceanus-hopkins-the-child-born-aboard-the-mayflower/ ) While much attention is focused on the men who came on the Mayflower, few people realize and take note that there were eleven girls on board, ranging in ages from less than a year old up to about sixteen or seventeen. William Bradford wrote that one of the Pilgrim's primary concerns was that the "weak bodies" of the women and girls would not be able to handle such a long voyage at sea, and the harsh life involved in establishing a new colony. For this reason, many girls were left behind, to be sent for later after the Colony had been established. Some of the daughters left behind include Fear Brewster (age 14), Mary Warren (10), Anna Warren (8), Sarah Warren (6), Elizabeth Warren (4), Abigail Warren (2), Jane Cooke (8), Hester Cooke (1), Mary Priest (7), Sarah Priest (5), and Elizabeth and Margaret Rogers. As it would turn out however, the girls had the strongest bodies of them all. No girls died on the Mayflower's voyage, but one man and one boy did. And the terrible first winter, twenty-five men (50%) and eight boys (36%) got sick and died, compared to only two girls (16%). So who were these girls? One of them was under the age of one, named Humility Cooper. Her father had died, and her mother was unable to support her; so she was sent with her aunt and uncle on the Mayflower. -

James Dufresne: They Met at Appomattox Court House

November 2017 Vol XXXIII, No 3 Thurs Nov 9 James Dufresne: They Met at Appomattox Court House “From present indications, the retreat of the enemy is rapidly becoming a rout.” So wrote Philip H. Sheridan to Lt Gen Ulysses S. Grant on April 5, 1865, from Jetersville Depot, Virginia, three days after Lee’s army had abandoned the trenches of the fallen cities of Richmond and Petersburg and begun its flight west. From the start, Grant’s goal was not merely to pursue Lee’s army but to intercept it: to cut it off and prevent Lee from veering south and joining the Confederate army of Joseph Johnston in North Carolina. Grant wanted to bring this war to a conclusion, so he ordered his two top generals, Sheridan and Sherman, to keep Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia constantly on the move. Lee’s army was in dire straits with very little food and ammunition remaining. Lee had planned to resupply his army at various points along his march west; however, he had little to no success. Grant had sent Sheridan and his command ahead with orders to destroy any supplies or ammunition that Lee might be able to acquire on his route west. He was also to intercept Lee’s army on its route wherever the time and place would allow. Sheridan did get the opportunity to stop Lee and his army at a place called Appomattox Court House. Gen Grant had been corresponding with Gen Lee for a couple of days previously while both were on the march. -

LIST of STATUES in the NATIONAL STATUARY HALL COLLECTION As of April 2017

history, art & archives | u. s. house of representatives LIST OF STATUES IN THE NATIONAL STATUARY HALL COLLECTION as of April 2017 STATE STATUE SCULPTOR Alabama Helen Keller Edward Hlavka Alabama Joseph Wheeler Berthold Nebel Alaska Edward Lewis “Bob” Bartlett Felix de Weldon Alaska Ernest Gruening George Anthonisen Arizona Barry Goldwater Deborah Copenhaver Fellows Arizona Eusebio F. Kino Suzanne Silvercruys Arkansas James Paul Clarke Pompeo Coppini Arkansas Uriah M. Rose Frederic Ruckstull California Ronald Wilson Reagan Chas Fagan California Junipero Serra Ettore Cadorin Colorado Florence Sabin Joy Buba Colorado John “Jack” Swigert George and Mark Lundeen Connecticut Roger Sherman Chauncey Ives Connecticut Jonathan Trumbull Chauncey Ives Delaware John Clayton Bryant Baker Delaware Caesar Rodney Bryant Baker Florida John Gorrie Charles A. Pillars Florida Edmund Kirby Smith Charles A. Pillars Georgia Crawford Long J. Massey Rhind Georgia Alexander H. Stephens Gutzon Borglum Hawaii Father Damien Marisol Escobar Hawaii Kamehameha I C. P. Curtis and Ortho Fairbanks, after Thomas Gould Idaho William Borah Bryant Baker Idaho George Shoup Frederick Triebel Illinois James Shields Leonard Volk Illinois Frances Willard Helen Mears Indiana Oliver Hazard Morton Charles Niehaus Indiana Lewis Wallace Andrew O’Connor Iowa Norman E. Borlaug Benjamin Victor Iowa Samuel Jordan Kirkwood Vinnie Ream Kansas Dwight D. Eisenhower Jim Brothers Kansas John James Ingalls Charles Niehaus Kentucky Henry Clay Charles Niehaus Kentucky Ephraim McDowell Charles Niehaus -

Senior Newsletter September 2017

T HE S ENIORS CENE Programs and Activities for Older Adults Programas y Actividades para Adultos Mayores Offered by: Division of Senior Services SEPTEMBER http://www.santafenm.gov/senior_scene_newsletter 2017 CITY OF SANTA FE, DIVISION OF SENIOR SERVICES Administration Offices 1121 Alto Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 SEPTEMBER - 2017 The City of Santa Fe Division of Senior Services offers a variety of programs and services at five senior centers throughout Santa Fe. If you are age 60 or over, we invite you to utilize our facilities and participate in the various programs and activities that are available, most of which are free (some do request a small donation). Read through the activities section for more information about ongoing and current activities. These facilities and services are here for you – we encourage you to stop by and use them, and we look forward to meeting you! The Senior Scene newsletter is a free monthly publication designed to help you navigate our services and learn about upcoming events. You will find sections on community news, senior center activities and menus, volunteer programs, 50+ Senior Olympics, health, safety, legal and consumer issues, as well as word puzzles to sharpen the mind. The newsletter is available at all City of Santa Fe senior centers, fitness facilities, and public libraries, as well as various senior living communities and healthcare agencies. It is also available online at www.santafenm.gov, simply type “Senior Scene” in the keyword search box at the top then click the purple underlined words “Senior Scene Newsletter.” Front Desk Reception (505) 955-4721 In Home Support Services: Respite Care, Toll-Free Administration Line (866) 824-8714 Homemaker Gino Rinaldi, DSS Director 955-4710 Theresa Trujillo, Program Supervisor 955-4745 Katie Ortiz, Clerk Typist 955-4746 Administration Cristy Montoya, Administrative Secretary 955-4721 Foster Grandparent/Senior Companion Program Sadie Marquez, Receptionist 955-4741 Melanie Montoya, Volunteer Prog. -

Harvest Ceremony

ATLANTIC OCEAN PA\\' fl.. Xf I I' I \ f 0 H I PI \ \. I \I ION •,, .._ "', Ll ; ~· • 4 .. O\\'\\1S s-'' f1r~~' ~, -~J.!!!I • .. .I . _f' .~h\ ,. \ l.J rth..i'i., \ inc-v •.u d .. .. .... Harvest Ceremony BEYOND THE THANK~GIVING MYTH - a study guide Harvest Ceremony BEYOND THE THANKSGIVING MYTH Summary: Native American people who first encountered the “pilgrims” at what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts play a major role in the imagination of American people today. Contemporary celebrations of the Thanksgiving holiday focus on the idea that the “first Thanksgiving” was a friendly gathering of two disparate groups—or even neighbors—who shared a meal and lived harmoniously. In actuality, the assembly of these people had much more to do with political alliances, diplomacy, and an effort at rarely achieved, temporary peaceful coexistence. Although Native American people have always given thanks for the world around them, the Thanksgiving celebrated today is more a combination of Puritan religious practices and the European festival called Harvest Home, which then grew to encompass Native foods. The First People families, but a woman could inherit the position if there was no male heir. A sachem could be usurped by In 1620, the area from Narragansett Bay someone belonging to a sachem family who was able in eastern Rhode Island to the Atlantic Ocean in to garner the allegiance of enough people. An unjust or southeastern Massachusetts, including Cape Cod, unwise sachem could find himself with no one to lead, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, was the home as sachems had no authority to force the people to do of the Wampanoag. -

America the Beautiful Part 1

America the Beautiful Part 1 Charlene Notgrass 1 America the Beautiful Part 1 by Charlene Notgrass ISBN 978-1-60999-141-8 Copyright © 2020 Notgrass Company. All rights reserved. All product names, brands, and other trademarks mentioned or pictured in this book are used for educational purposes only. No association with or endorsement by the owners of the trademarks is intended. Each trademark remains the property of its respective owner. Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are taken from the New American Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by the Lockman Foundation. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Cover Images: Jordan Pond, Maine, background by Dave Ashworth / Shutterstock.com; Deer’s Hair by George Catlin / Smithsonian American Art Museum; Young Girl and Dog by Percy Moran / Smithsonian American Art Museum; William Lee from George Washington and William Lee by John Trumbull / Metropolitan Museum of Art. Back Cover Author Photo: Professional Portraits by Kevin Wimpy The image on the preceding page is of Denali in Denali National Park. No part of this material may be reproduced without permission from the publisher. You may not photocopy this book. If you need additional copies for children in your family or for students in your group or classroom, contact Notgrass History to order them. Printed in the United States of America. Notgrass History 975 Roaring River Rd. Gainesboro, TN 38562 1-800-211-8793 notgrass.com Thunder Rocks, Allegany State Park, New York Dear Student When God created the land we call America, He sculpted and painted a masterpiece. -

Charles Warren Fairbanks (1852–1918)

Charles Warren Fairbanks (1852–1918) A prosperous Indianapolis attorney who eoclassical sculptor Franklin Simmons specialized in was active in the Republican Party, depicting Americans and American history, though he Charles Warren Fairbanks served as both a U.S. senator from Indiana and 26th vice spent most of his career in Rome. Born and raised in president of the United States. Born in Maine, Simmons briefly studied under John Adams Union County, Ohio, Fairbanks was a Jackson in Boston. For two years in the mid-1860s, the keynote speaker at the 1896 Republican sculptor lived in Washington, D.C., and modeled Civil War officers National Convention that nominated N William McKinley for president. In that Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, and David G. Farragut. Soon after- same year, Fairbanks was elected to the ward, Simmons moved to Rome, where, like others of his generation, U.S. Senate, where he served from 1897 to 1905, chairing the Committee on Immi- he was attracted by the availability of materials and assistants and by gration and the Committee on Public the creative environment. Buildings and Grounds. Charles Fairbanks was vice president-elect in 1905 when he sat A leading conservative, Fairbanks was nominated for the vice presidency on the for the bust intermittently during visits to Washington. The sculptor, who 1904 ticket with Theodore Roosevelt. Upon had previously created busts of Vice Presidents Hannibal Hamlin (p. 180) election, Fairbanks resigned from the and Adlai E. Stevenson (p. 344) for the U.S. Capitol, apparently believed Senate. Although he was a favorite son candidate for the Republican nomination that his proposal for a likeness of Fairbanks had been officially accepted. -

Massasoits Town Sowams in Pokanoket

’ Massasoit s Town S owam s i n P okan oke t I TS H I S TO RY L EG EN D S A RA N D T D I TI ON S . By V I RGI NIA B AKE R Auth or of H t f W rr n R I i n h e W ar of th e R v lut n The s or o a e . t e o i y , o i LIB Q A n Y o f (30 51 6 9 63 5 Two C opi e s Rece i ve d MAR g 1904 Copyri g h t k wi ry 8 l w a x . 0 t g Cb C LAS S XXc. No ' fi 8 8 8f d ’ C OPY ' W rren 'ere r t be e the r le n t on a wh fi s sid c ad d a i , The old e too we love t tor e t chi f s d , hy s i d pas , S owam s is ple asan t for a habitation ’ — Twas thy first history may it be thy las t . — B W HE Z E KI AH UTTE R ORTH . C opy rig h t 1 904 b y V i rg i ni a B a k e r ’ M a s s a s o i t s T o w n S o w a m s i n P o k a n o k e t PECULIAR interest centres about everything per the s s s s taining to great Wampanoag achem Ma a oit . -

For Christmas I'd Like Betty Aldrich Iowa State College

Volume 23 Article 5 Number 5 The Iowa Homemaker vol.23, no.5 1943 For Christmas I'd Like Betty Aldrich Iowa State College Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/homemaker Part of the Home Economics Commons Recommended Citation Aldrich, Betty (1943) "For Christmas I'd Like," The Iowa Homemaker: Vol. 23 : No. 5 , Article 5. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/homemaker/vol23/iss5/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oI wa Homemaker by an authorized editor of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Betty Aldrich describe bring holiday sparkle f, ICKY will usher in the holiday sea low-heeled comfortable shoes the most V son with a flattering wardrobe in popular. But for dress, the opera pump spite of the curtailment of her wartime is still the hit of the coupon No. 18 era clothes budget. Christmas presents and would be an ideal Christmas pres which add to Vicky's wardrobe will be ent. especially welaome this year-particu Gone are the days when Vicky bought larly if they are convertible clothes which the first thing that looked pretty, re can be the foundation of numerous gardless of quality. A duration sensation smart, though inexpensive outfits. in her wardrobe is a dress of flame cash Vicky would be happy to find a dou mere wool. Its dash is carried out in such ble-purpose wool suit under the tree details as the buttoned patch pockets and Christmas morning. -

Why the Dutch? the Historical Context of New Netherland

1 Why the Dutch? The Historical Context of New Netherland Charles T. Gehring The past is elusive. No matter how hard we try to imagine what the world was like centuries ago, the attempt conjures up only blurry images, which slip away like a dream. However, we do have tools available to sharpen these images of the past: primary source materials and archaeological evi- dence. With both we can attempt to construct a world in which we never lived. If we have any advantage at all, it’s only that we know what that past world’s future will be like.proof The goal of this book is to provide the latest archaeology of the area that the Dutch once called Nieuw Nederlandt. As an increasing number of translations of the records of this West India Company (WIC) endeavor become available to researchers, it is hoped that this collection of articles will enhance the words that the Dutch left behind. It’s fitting that we review why the Dutch were here in the first place. Most of the narrative facts of the Dutch story are well known and ac- cepted among historians who specialize in the history of the Dutch Repub- lic and its colonial undertakings. Accordingly, I use citations here spar- ingly; however, the reader wishing a deeper understanding should consult the sources cited at the end of this chapter. In the seventeenth century, the Dutch possessions lay between the New England colonies to the northeast and the tobacco colonies of Maryland and Virginia to the southwest. In 1614 the region appeared in a document of the States General of the United Provinces of the Netherlands as New Netherland.