A Special Investigation of the Bethlehem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gingrich Winning in Both Arizona and Pennsylvania

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE November 21, 2011 INTERVIEWS: Tom Jensen 919-744-6312 IF YOU HAVE BASIC METHODOLOGICAL QUESTIONS, PLEASE E-MAIL [email protected], OR CONSULT THE FINAL PARAGRAPH OF THE PRESS RELEASE Gingrich winning in both Arizona and Pennsylvania Raleigh, N.C. – Newt Gingrich's momentum in the Republican Presidential race is just continuing to grow as Herman Cain's support fades away. Gingrich leads the GOP field in both Pennsylvania and Arizona. In Pennsylvania Gingrich has 32% to 15% for Cain, 12% for Mitt Romney and Rick Santorum, 9% for Ron Paul, 5% for Michele Bachmann, 3% for Rick Perry and Jon Huntsman, and 0% for Gary Johnson. In Arizona Gingrich has 28% to 23% for Romney, 17% for Cain, 8% for Paul, 5% for Huntsman, 3% for Bachmann, Perry, and Santorum, and 0% for Gary Johnson. Gingrich's leads are a result of Cain's support finally starting to really fall apart. For an 8 week period from the end of September through last week Cain was over 20% in every single poll we did at the state or national level. Over that period of time we also repeatedly found that Gingrich was the second choice of Cain voters. Now that Cain has slipped below that 20% threshold of support he had consistently held, Gingrich is gaining. There's reason to think Gingrich could get stronger before he gets weaker. In Pennsylvania he's the second choice of 49% of Cain voters to 10% for Romney. And in Arizona he's the second choice of 39% of Cain voters to 10% for Romney. -

2001-2002 Appropriations Hearings University of Pittsburgh

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS In re: 2001-2002 Appropriations Hearings University of Pittsburgh * * * * Stenographic report of hearing held in Majority Caucus Room, Main Capitol Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Wednesday February 28, 2001 9:00 A.M. HON. JOHN E. BARLEY, CHAIRMAN Hon. Gene DiGirolamo, Secretary Hon. Patrick E. Fleagle, Subcommittee on Education Hon. Jim Lynch, Subcommittee on Capitol Budget Hon. John J. Taylor, Subcommittee/Health and Human Services Hon. Dwight Evans, Democratic Chairman MEMBERS OF APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE Hon. William F. Adolph Hon. Steven R. Nickol Hon. Matthew E. Baker Hon. Jane C. Orie Hon. Stephen Barrar Hon. William R. Robinson Hon. Lita I. Cohen Hon. Samuel E. Rohrer Hon. Craig A. Dally Hon. Stanley E. Saylor Hon. Teresa E. Forcier Hon. Curt Schroder Hon. Dan Frankel Hon. Edward G. Staback Hon. Babette Josephs Hon. Jerry A. Stern Hon. John A. Lawless Hon. Stephen H. Stetler Hon. Kathy M. Manderino Hon. Jere L. Strittmatter Hon. David J. Mayernik Hon. Leo J. Trich, Jr. Hon. Phyllis Mundy Hon. Peter J. Zug Hon. John Myers Also Present: Michael Rosenstein, Executive Director Mary Soderberg, Democratic Executive Director Reported by: Nancy J. Grega, RPR ADELMAN REPORTERS 231 Timothy Road Gibsonia, Pennsylvania 15044 724-625-9101 INDEX Witnesses; Page Dr. Mark A. Nordenberg, Chancellor 4 Dr. James V. Maher, Provost and Senior Vice Chancellor Dr. Arthur A. Levin 26 CHAIRMAN BARLEY: This is day three of the first week of our hearings. We have before us today the University of Pittsburgh but as we have been doing customarily at this point, I will provide the members that are with us an opportunity to make brief introductions of themselves for the benefit of the audience. -

TEA Party Exposed by ANONYMOUS Political Party

ANONYMOUS Political Party would like to take the pleasure to introduce The TEA Party /// Tobacco Everywhere Always this DOX will serve as a wake-up call to some people in the Tea Party itself … who will find it a disturbing to know the “grassroots” movement they are so emotionally attached to, is in fact a pawn created by billionaires and large corporations with little interest in fighting for the rights of the common person, but instead using the common person to fight for their own unfettered profits. The “TEA Party” drives a wedge of division in America | It desires patriots, militias, constitutionalists, and so many more groups and individuals to ignite a revolution | to destroy the very fabric of the threads which were designed to kept this republic united | WE, will not tolerate the ideologies of this alleged political party anymore, nor, should any other individual residing in this nation. We will NOT ‘Hail Hydra”! United as One | Divided by Zero ANONYMOUS Political Party | United States of America www.anonymouspoliticalparty.org Study Confirms Tea Party Was Created by Big Tobacco and Billionaires Clearing the PR Pollution That Clouds Climate Science Select Language ▼ FOLLOW US! Mon, 2013-02-11 00:44 BRENDAN DEMELLE SUBSCRIBE TO OUR E- Study Confirms Tea Party Was Created by Big NEWSLETTER Get our Top 5 stories in your inbox Tobacco and Billionaires weekly. A new academic study confirms that front 12k groups with longstanding ties to the tobacco industry and the billionaire Koch Like DESMOG TIP JAR brothers planned the formation of the Tea Help us clear the PR pollution that Party movement more than a decade clouds climate science. -

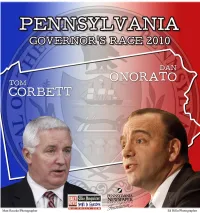

Corbett Leads Unknowns in Pennsylvania Governor's Race, Quinnipiac University Poll Finds; Voters Oppose Rendell Sales Tax

Peter Brown, Assistant Director, Quinnipiac University Polling Institute FOR RELEASE: MARCH 3, 2010 CORBETT LEADS UNKNOWNS IN PENNSYLVANIA GOVERNOR’S RACE, QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY POLL FINDS; VOTERS OPPOSE RENDELL SALES TAX PLAN Pennsylvania Attorney General Tom Corbett has a 43 – 5 percent lead over State Representative Sam Rohrer for the Republican nomination for governor and holds double-digit leads over the top Democratic candidates, all of whom who are virtual unknowns even to their own party members, according to a Quinnipiac University poll released today. “Don’t know” leads the field for the Democratic nomination with 59 percent, followed by Allegheny County Executive Dan Onorato with 16 percent, State Auditor General Jack Wagner with 11 percent, 2004 U.S. Senate nominee Joel Hoeffel at 10 percent and State. Sen. Tony Williams at 2 percent, the independent Quinnipiac (KWIN-uh-pe-ack) University poll finds. Gov. Ed Rendell remains unpopular with voters as he completes his final year in office, as voters disapprove 49 – 43 percent of the job he is doing, unchanged from December 17. Voters say 49 – 6 percent Gov. Rendell’s plan to increase state spending next year by 4.1 percent was too much rather than too little. Another 35 percent say it’s about right. By a 53 – 40 percent margin, voters oppose the Governor’s plan to raise more money by cutting the state sales tax but expanding items covered by it. “The Democratic candidates for Governor are almost invisible men as far as the voters are concerned. One of them will win the nomination, but at this point they are so closely bunched together and such mystery men to the vast majority of primary voters that any result is possible, given that the primary is little more than 10 weeks away,” said Peter Brown, assistant director of the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute. -

Verizon Political Contributions January – December 2008 Verizon Political Contributions January – December 2008 1

VERIZON POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS JANUARY – DECEMBER 2008 Verizon Political Contributions January – December 2008 1 A Message from Tom Tauke Verizon is affected by a wide variety of government policies — from telecommunications regulation to taxation to health care and more — that have an enormous impact on the business climate in which we operate. We owe it to our shareowners, employees and customers to advocate public policies that will enable us to compete fairly and freely in the marketplace. Political contributions are one way we support the democratic electoral process and participate in the policy dialogue. Our employees have established political action committees at the federal level and in 25 states. These political action committees (PACs) allow employees to pool their resources to support candidates for office who generally support the public policies our employees advocate. This report lists all PAC contributions and corporate political contributions made by Verizon in 2008. The contribution process is overseen by the Corporate Governance and Policy Committee of our Board of Directors, which receives a comprehensive report and briefing on these activities at least annually. We intend to update this voluntary disclosure twice a year and publish it on our corporate website. We believe this transparency with respect to our political spending is in keeping with our commitment to good corporate governance and a further sign of our responsiveness to the interests of our shareowners. Thomas J. Tauke Executive Vice President Public -

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania House of Representatives

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES GAME AND FISHERIES COMMITTEE HEARING STATE CAPITOL RYAN OFFICE BUILDING ROOM 205 HARRISBURG, PENNSYLVANIA THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 14, 2008 9:00 A.M. PRESENTATION ON PENNSYLVANIA FISH AND BOAT COMMISSION BEFORE: HONORABLE EDWARD G. STABACK, CHAIRMAN HONORABLE ANTHONY M. DeLUCA HONORABLE GORDON R. DENLINGER HONORABLE GARTH D. EVERETT HONORABLE KEITH J. GILLESPIE HONORABLE NEAL P. GOODMAN HONORABLE GARY HALUSKA HONORABLE ROB KAUFFMAN HONORABLE DEBERAH KULA HONORABLE TIM MAHONEY HONORABLE DAVID R. MILLARD HONORABLE DAN MOUL HONORABLE MICHAEL PEIFER HONORABLE SCOTT PERRY HONORABLE HARRY A. READSHAW HONORABLE SAMUEL E. ROHRER HONORABLE CHRIS SAINATO HONORABLE DAN A. SURRA DEBRA B. MILLER REPORTER 2 1 I N D E X 2 TESTIFIERS 3 4 NAME PAGE 5 DR. DOUGLAS J. AUSTEN 4 6 MR. GARY MOORE 82 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 3 1 CHAIRMAN STABACK: The hour of 9 o'clock 2 having arrived, I will call the hearing of the House 3 Game and Fisheries Committee to order. 4 Today we are here to take testimony in the 5 form of the annual report from the Pennsylvania Fish 6 and Boat Commission. 7 Before we get into that, I would like the 8 members of the Committee that are present to identify 9 themselves and the districts that they represent, 10 starting with myself. 11 Ed Staback, Chairman of the Committee. I 12 represent the mid and upper valley of Lackawanna 13 County and southern Wayne County. 14 Starting on my left. -

Franklin & Marshall

For immediate release Wednesday, May 12, 2010 May 2010 Franklin & Marshall College Poll SURVEY OF PENNSYLVANIANS SUMMARY OF FINDINGS Prepared by: Center for Opinion Research Floyd Institute for Public Policy Franklin & Marshall College BERWOOD A. YOST DIRECTOR, FLOYD INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY DIRECTOR, CENTER FOR OPINION RESEARCH HEAD METHODOLOGIST, FRANKLIN & MARSHALL COLLEGE POLL G. TERRY MADONNA DIRECTOR, CENTER FOR POLITICS AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS DIRECTOR, FRANKLIN & MARSHALL COLLEGE POLL ANGELA N. KNITTLE SENIOR PROJECT MANAGER, CENTER FOR OPINION RESEARCH PROJECT MANAGER, FRANKLIN & MARSHALL COLLEGE POLL KAY K. HUEBNER PROGRAMMER, CENTER FOR OPINION RESEARCH May 12, 2010 Table of Contents METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................................... 2 KEY FINDINGS ........................................................................................................................ 4 THE DEMOCRATIC US SENATE PRIMARY .................................................................................4 OTHER PENNSYLVANIA PRIMARY RACES .................................................................................7 ABOUT THE LIKELY VOTER MODEL .........................................................................................8 TABLE A-1 ............................................................................................................................... 9 MARGINAL FREQUENCY REPORT .....................................................................................10 -

CERTIFICATE on ELECTION EXPENSES Paul I

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA LEGISLATIVE JOURNAL TUESDAY, JANUARY 5,1993 SESSION OF 1993 17TTH OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY No. 1 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES troublesome times, finding in the examples hmow Nation's past steadfastness of spirit and strength of will not only to ANNOUNCEMENT behold the right but to meet its challenge. Remember, too, that this building has seen the mortal illness At 11:30 a.m., the HONORABLE MA.1-TIIEW J. RYAN, and death of many elected officials, one of the most recent of a member-elect from llelaware County, made the following which that of James Manderino, the rock of Monessen, ought announcement in the hall of the House: to serve to remind all who labor in this legislative vineyard that the Sun's majesty does not shine only on this building to In accordance with the provision5 of Article 11, section 4, of the exclusion of the rest of the that those who the Conslitut~on of Pennsylvania, the members-elect of the work here - to maintain a reservoir of Rood humor House of Representatives will meet thls day at 12 o'clock noon emotional detachment, trusting their own to in the hall of the House of Representatives for the purpose of . I same to opponent; remembering, too, that organlzatlon. I des~ite evidence to the contrary, one's own intellectual judgment on a bill or issue may possibly be in error and that, CALL TO ORDER believe it or not, the other fellow may possibly be right. I Neither side has a monopoly on the good and the true and The hour of 12 o'clock having amvcd, the IfONOKhSLE the beautiful. -

2010 GENERAL ELECTION CANDIDATE GUIDEBOOK Table of Contents

2010 GENERAL ELECTION CANDIDATE GUIDEBOOK Table of Contents Gubernatorial Race Page 2 Pennsylvania Governor Edward G. Rendell is term-limited. Republican Tom Corbett and Democrat Dan Onorato are facing off in the General Election for a four-year term. Their respective running mates are Jim Cawley and Scott Conklin. U.S. Senate Race Page 3 U.S. Senator Arlen Specter (D) was defeated in the Democrat Primary Election by Congressman Joe Sestak. The Republican nominee is former Congressman Pat Toomey. The two are vying for a six-year term. Congressional Races Pages 4-9 Pennsylvania’s 19 seats in the US House of Representatives are filled in every even-year election for two- year terms. All but one incumbent is seeking re-election. The 7th Congressional District is the only “open election” among Pennsylvania’s Congressional Delegation. State Senate Races Pages 10-12 One-half of Pennsylvania’s 50 state Senate Districts are filled in each even-year election. 22 of the 25 state Senators in those districts facing election are seeking re-election, leaving three “open seats” – all three open seats are being defended by the Democrats. Seven members of the state Senate (3 Republican/4 Democrat) are unopposed for re-election. State House Races Pages 13-33 All of Pennsylvania’s 203 state House Districts are filled in each even-year election. There are 17 open seats – 7 defended by the Republicans and 10 defended by the Democrats. 77 members of the House (41 Republican/36 Democrat) are unopposed for re-election. ABOUT PEG PAC The Pennsylvania Business Council’s political endorsements, political contributions and political action are made by the affiliated PEG PAC. -

Governor.Pdf

The Pennsylvania Governor’s Race 2010 Dear Students: Every four years, elementary and high school teachers scramble to gather materials that will enhance their curriculum Politics in the News regarding the Governor’s Election (Nov. 2, 2010). They have No matter what time of the year it is, there are always some the tough job of trying to explain this important election political stirrings being reported on in your local newspaper. Think process to you and the affects local politics will have on your about how many months go by when a President is campaigning. Every life. day the press is talking about some type of update. Look through the pages of your newspaper for a story about a candidate either running or From explaining what the election process is to identifying the in office. What is the story about? Why do you think this story should role of newspapers in this process, teachers, in their own ways, or shouldn’t be in the news? expose students to this precious right – freedom to choose a governor. This right may be the most important one, as it gives you a voice in the way the government works. Without a voice, freedom is not a certain advantage. Media Media Everywhere This guide, “Pennsylvania Governor’s Race 2010,” was Today, there are so many media outlets, it isn’t just newspapers that created to give teachers a resource to help explain these get the big story. Think about the immediate media sources that you important government processes. We have found that many can get up to date information from. -

N Re: 2000-2001 Appropriations Hearings Department of Community and Economic Development

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS [n re: 2000-2001 Appropriations Hearings Department of Community and Economic Development * * * Stenographic report of hearing held in Majority Caucus Room, Main Capitol Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Monday March 6, 2000 10:00 a.m. iON. JOHN 2. BARLEY, CHAIRMAN Ion. Gene DiGirolamo, Secretary ton. Patrick E. Fleagle, Subcommittee on Education Ion. Jim Lynch, Subcommittee on Capitol Budget Ion. Ron Raymond, Subcommitee on Health and Human Services ton. Dwight Evans, Minority Chairman MEMBERS OF APPROPRIATIONS COMMITTEE Ion. William F. Adolph Hon. Steven R. Nickol Ion. Matthew E. Baker Hon. Jane C. Orie Ion. Lita I. Cohen Hon. Joseph Preston, Jr. Ion. Craig Dally Hon. William Russell Robinson Ion. Teresa E. Forcier Hon. Samuel E. Rohrer ton. Dan Frankel Hon. Stanley E. Saylor ton. Babette Josephs Hon. Curt Schroder ton. George Kenney Hon. Edward Staback Ion. Frank LaGrotta Hon. Jerry A. Stern ton. John A. Lawless Hon. Stephen H. Stetier ton. Kathy Manderino Hon. Jere L. Strittmatter ton. Phyllis Mundy Hon. Leo J. Trich, Jr. Ion. John Myers Hon. Peter J. Zug Uso Present: Aichael Rosenstein, Executive Director Reported by: Dorothy M. Malone, RPR Dorotn4 M. M-l one Registered Professional Reporter 135 S- LanJis Street Hummelctown, Pennsijlvania 17036 \/ Also Presnt; (Cont'd) Mary Soderberg, Minority Executive Director Erik Randolph, Budget Analyst Dorol^ M- Malone Registered Professional Reporter 135 S- LanJis S*i«et {—lummelstown, Pennsylvania 17036 CHAIRMAN BARLEY: Good morning everyone and I would like to call the 'hearing to order and ask the members to be seated. Those making presentations if they would take their places. -

Budget Appropriation

1/30/13 Right Makes Might | Philadelphia City Paper | 07/28/2011 [ search ] login / register | contact us | contests NEWS FOOD/DRINK A&E BLOGS FEATURES CLASSIFIEDS LOVE/HATE ARCHIVES About Us Advertise With Us Staff Subscriptions Privacy Policy email print font size 3 comments Recommend 0 Contact Us Submit Your Event Jobs & Internships Posted: Thu, Jul. 28, 2011, 3:00 AM © Copyright 1995 2012 Philadelphia City Paper. All Rights Reserved. Right Makes Might Meet Daryl Metcalfe, the guntoting, gaybashing, teapartying state rep who's taking over Harrisburg. Daniel Denvir State Rep. Daryl Metcalfe, a guntoting 48yearold who represents Pittsburgh's fastgrowing, farout Butler County exurbs, has spent more than a decade slogging his way toward power. For years, he was a nobody in Harrisburg, and the media paid far more attention to his strongworded comments about gays, guns and immigrants than his colleagues ever did to his legislation. But in the wake of President Barack Obama's election, things changed: A national movement of angry conservatives took hold and voted out any Republicans or Democrats who smelled of moderation. Or, as Metcalfe put it to the liberal news website Talking Points Memo, "I was a Tea Partier before it was cool." In 2010, as rightwing challengers took on establishment conservatives nationwide, Metcalfe ran for lieutenant governor, promising to be an ideological watchdog rather than a running mate: "If Pennsylvania's next governor breaks his word and raises taxes, supports more government programs that redistribute wealth or signs laws that infringe on our Constitutional rights, then I will publicly expose his actions and be ready to challenge him in the next primary election," he wrote in a letter to Republican State Committee members.