ARTISTS and ANARCHISM ANARCHY 91 2/- Or 30¢

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anarchist Weekly • Who Will Rid Us of This Meddlesome Priest ?

No Voles of Eighteen! Anarchist Weekly • EVERYBODY KNOWS THAT not idealists (have no ideals), who representative of a minority as the youngsters mature much earlier are realists (have no principles), who old ones. The leaders become the NOVEMBER 16 1968 Vol 29 No 35 nowadays. Puberty at 13, 12 or are adjusted (have no imagination). new elite; the rank and file begin a even 11 is regulation—the late But what if the youngsters won't new experience in disillusionment. starter begins to think something is be fobbed off with lies, spit out the 4. You isolate the real revolutionaries. wrong! What with the permissive soothing syrup, answer the gentle These are the hard core of real direct society, Dr. Spock, bless him, pro- actionists who embrace direct action pat with a smack in*the mouth— as a principle not as a tactic, because gressive parents (if you're lucky), what then? What if the society of what they want—a reorganisation propaganda for the pill, a vague the squares does not impress them, of society without any government grasp of what Reich was on about, in fact disgusts them? What if they at all—cannot be achieved by playing Who will rid us of and the beat, beat, beat of the pop want to run their own world on their politics and choosing masters. Once group hammering at our heart- own terms and begin to find ways isolated, these can be deah with by all strings, to fix the 'age of consent' at and means, to bring it all about? the extra-parliamentary methods that 16 seems a bloody imposition. -

Freedom Is for Taking

munreMstmaweeUty 5P Vol. 35 No. 31 3 August, 1974 LIBERTY, MORALITY, AND THE HUMAN DIGNITY OF MAN CONSIST PRECISELY IN THIS, THAT HE DOES GOOD, NOT BECAUSE IT'IS COMMANDED, BUT BECAUSE HE CONCEIVES IT, WILLS IT, AJTO LOVES IT. Bakunin. Cyprus: FREEDOM IS FOR TAKING WILE THE wrangling is still power and slaughter punctuate Makarios or Clerides? Indeed we going on about Cyprus — the the Byzaitine mess of this bar- once interned Makarios. Turks; confident in their nine gaining pressure point of the The centuries old enmity bet- points of possession; the Near East. ween Greece and Turkey is no bar Greeks uneasy in their loss of to the N.A.T.O. alliance or the face but acquisition of late It is obvious that neither British bases. Indeed, to spon-' respectability; the U-nited Na- Turkey nor Greece nor Makarios' sor a conflict in an occupied tions baffled in the prospective Cyprus are enlightened regimes; country between the 'natives' is threat to N.A.T.O.; the British all are equally adept at politi- an old trick of conquerors. They conscious of their powerlessness cal persecution and torture and are then so busy arguing between •and need to keep their bases; even the re-exhumed Karamanlis themselves that they cannot see U.N.O. conscious (as ever) of sponsored an eight-year regime what the occupiers (whether they its impotence in the face of not without blemish. The charac- be American NATO bases or Brit- power and Russia sitting-in ter of the regimes in Turkey and with poker-playing impassivity Greece is a matter of indiffer- ish NATO bases) are putting over — we only see the Cypriots (be ence to the United States, its on them. -

Scanned Image

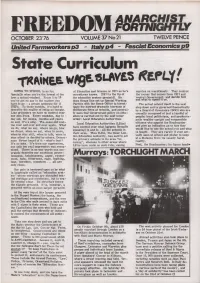

R HI T OCTOBER 2376 VOLUME 37 No 21 TWELVE PENCE UnitedFarmworkersn3 ~ Italyn4 - FascistEconomics£9 Aiuse LN/£5 e. 1.! GOING TO SCHOOL is no fun. of Education and Science or DES as he's carries on mercilessly. They control Specially when you're the lowest of the sometimes known. (DES is the tip of the money that comes from DES and low: a school-student. From 5 to 16 the education system pyramid). He central Government. and decide how you've got no say in the matter: you does things like set up Special Working and what to spend it on. have to go - a prison sentence for ll Parties with the Home Office to invest- The actual school itself is the next years. To those outside, it's hard to igate the current dramatic increase of step down and is governed theoretically describe the reality of being an inmate. deliberate fires at schools, and general- by a Board of Governors (BOG) who are Like prisoners we have no control over ly sees that Government policy on educ- ususally composed of just a handful of our own lives. Every weekday, day in - ation is carried out by the next lower people; local politicians, and predomin- day out, for weeks, months and years order: Local Education Authorities. antly wealthy upright and responsible on end, it's a slog. The same old rout- Local Education Authorities (LEAs) citizens who appoint the Headmaster ine over and over and over again. What and give an indication as to how they we do, what we say, where we go, how " have control over what happens (broadly speaking) in and to - all the schools in would like to see the school run and what we dress, when we eat. -

Hethel, Norfolk 11 Born Again 12 Busyness

Trials and Inspirations Autobiography of John Myhill Contents 1 Hong Kong Child 2 Primary Guides 3 Annals of the Parish 4 Secondary Boyhood 5 University 6 Research 7 Real Life 8 Wisdom from the Past 9 Mental Distress 10 Hethel, Norfolk 11 Born Again 12 Busyness Copyright 2013, John Myhill, all rights reserved. The views contained in this book are those of John Myhill alone. The names of some people have been changed to protect their anonymity Hong Kong Child Birth I was born in a tropical thunderstorm, never to be forgotten by the doctor called out to attend my mother. It was reminiscent of the storm outside Wuthering Heights when the ghost of Cathy tries to get in. But it was the spirit of Gandhi that entered my life. The date was September 28, 1948. We were living in Hong Kong, where my father was headmaster of St Stephen’s College missionary school I cannot remember a time when I just experienced events without reflecting upon the experience, but my reflections were determined by what I saw and what I saw in dreams was more powerful than what I saw when awake. What I saw in films and cartoons, and later through books and conversation, was closer to my dreams and thus more influential on my thinking. Before my memories begin, my father mentions in his diary: “Miss Scott Moncrieff” 12/03/1952. I would not be writing if the Scott Moncrieff (1889-1930) translation of Proust’s (1871-1922) great work had not inspired me. The certainty that one memory will provide another, until we not only understand the characters and their author, but ourselves and our own fulfilment of Being. -

F Volu»E 34 N'o. 51 22 December, 1973 Ul Mi |L

f 5p Volu»e 34 N'o. 51 22 December, 1973 Ul Mi |L BOTH Mr. Heath, the Prime Mini stake in the capitalist syst It is not the job of the pro ster, and Mr. Wilson, leader of em and to do-operate with the ducers of wealth to save frn» the Opposition, have appealed employers and government to disaster those who exploit to the British public for a perpetuate their own economic their labour for profit and po sense of national unity in ord and political slavery. The wer. Already t*he miners, rail er to face and overcome the en people who have produced the way men and electrical engineers ergy and economic crises. It wealth are once again called have shown where power really now becomes a patriotic duty of upon to save the system which lies. Their labour, like that everyone to assist the nation is "walking on the edge of a of all workers, has been taken to pull through the present precipice". But it is only a so much for granted. Many who difficulties. Arthur Moyse's minority who own and control don't actually produce them cartoon expressed this so well the industrial wealth of this selves or perform any useful last week with his caption country. It is only a minor work look upon those who do as "It's curious but the country ity who operate and control their servants. Like some only becomes ours when there's the repressive institutions of "god-ordained order" they ex a bloody war or we're on strike” the State. -

The Rape of the Couhtryside

Nationalism and Freedom One of the most interesting phases of the great revolt is the agitation tion, begin to put up candidates for elec- of the Keltic populations, if not for a free land, at least for land less tions or even to form armies. (Anarchists are not necessarily pacifists, but an anar- MARCH 15 1969 Vol 30 No 8 heavily burdened for the maintenance of their Teutonic masters. Foreign competition has reduced the value of agricultural produce by something chist army is difficult to visualise, like half. But the non-producing classes, i.e. proprietors and clergy, although I believe something of the kind was tried in Spain.) Or become, as they and farmers in localities where these have been bitten by the idea of sometimes do, racist. To make a religion degrading themselves from workers into gentlemen—are struggling to out of the Welsh or Irish languages, or of wring the same unearned benefit from the toil of the labourers as before. having a black skin, is no more sense Amongst the Keltic peoples this attempt to extort the uttermost farthing than making a religion out of the tongue is aggravated by antagonism of race, by the tradition of conqueror of Shakespeare, or out of Norman or THE RAPE OF and conquered, by the imposition of an alien law. The tithe war in . Saxon blood. Anarchists have many Wales is a current example. These tithes are an arbitrary charge upon bitter experiences of the results of sup- the rent of the land, varying from 6d. to 10s. 4d. -

Anarchist Ioflniehfls

anarchist ioflniehfls 12 Se!’ *6’"be"_1_?§_¥,_lf0l. 4.2.» No.1 8 FREEDOM has not had a good hard look The Ukraine used to be referred to as Soviet leaders obviously, for all their at Poland for exactly one year. Our last the ‘breadbasket of Europe’. Now oddly Marxist ideology, have contempt for the front page headline on Poland (13th Sept enough, year after year, there is crop workers, just like capitalists have. 80), was: ‘The Betrayal Begins’. failure after crop failure, while across the But what about these workers in Well, surprise, surprise, the betrayal in Atlantic, in spite of the fearful results of Poland? September 1980, that seemed to begin, the dustbowls of the 30’s, due to the never really got off the ground. For the erosion caused by overcropping, abun- Somehow, without the party hier- fact is that the real betrayal began in dance follows abundance year after year. archy realising it, subversive ideas have October 1917 when the bourgeois So Russia buys food from America, year been spreading, steadily but firmly. Ten counter-revolution began with the Bol- after year. years of stability, apparent servility, can shevik seizure of power. Ever since then, There is of course a price to pay for breed a smugness in a ruling class de- the ability of the men in the Kremlin to that. It is Western investment in the tached from the grass roots. (Compare react to a threat other than by an ex- Soviet economy -— that other kind of our own ruling class, here, and the anger hibition of naked power has seemed im- erosion: the inroads of foreign investment among the young!) And it is now very Dossible. -

Black Flag Supplement

-I U The oodcock - Sansom School of Fals|f|cat|o (Under review: the new revised edition of Geo. Woodcock’s no mnnection with this George Spanish). The book wrote the Anarchists off ‘Anarchism’, published by Penguin books; the Centenary Edition Woodcock! Wrote all essay 111 3 trade altogether. The movement was dead. of ‘Freedom’, published by Freedom Press.) ‘figiggmfii“,:§°:i;mfit‘3’§ar’§‘,ia’m,‘§f“;L3;S, He was its ‘obituarist’. Now he has fulsome praise of his ‘customary issued a revised version of the book brilliance (he had only written one brought up ‘to date’. He wasn’t HEALTH WARNING; Responses to preparing for a three volume history °i3iiei' Pieee) and ’iiiei5iVe insight’ " it wrong, he says, it did die — but his (‘I find the influence of Stirner on was a Pavlovian response from his book brought it back to life again! Freedom Press clique have been namesake’s coterie. It explains what It adds a history’ of the British described by our friends as ‘terminally British anarchism very interesting. .’) The Amsterdam Institute for Social this George Woodcock set out movement for his self-glorification, boring’ but can we let everything History, funded by the Dutch govem- steadily to build up. actually referring to the British pass? We suggest using this as a ment, now utilises the CNT archives He came on the anarchist scene delegate to the Carrara conference supplement to either ‘Anarchism’ or to establish itself (to quote Rudolf de during the war, profiteering on the denouncing those who pretended to ‘Freedom Centennial’, especially when Jong) as ‘paterfamilias’ between the boom in anarchism to get into the be anarchists but were so in name you feel tired of living. -

Üddon's COSMOPOLITAN REVIEW Vol.L.No.L

üddon's COSMOPOLITAN REVIEW Vol.l.No.l. ^U April. 13.1965. THE BENEFITS MORAL AND SECULAR OF ASSASSINATION If authority success and eugenic usefulness can sanction homicide,then history records numerous murders which have fulfilled the expectations of their perpetrators,and the names of the assassins command the respect all who value statecraft,wisdom and courage; for they were the very pillars of all the most successful of older governments. Those most pleasant to live within and most high in achievement. In the best of these the strongest assassin was the king,for so long as his courage and administrative ability sustained his right to office, and degeneration or abuse of power was corrected by violent dethronement or assassination. The wiser public opinion of the ancient world every where approved of assassination as an instrument of political or racial improvement. Works of art abounded. Since that golden age,it must be confessed,the art has seen only retro gression almost unchecked. Occassionally some generation or isolated community,by an effort of intellectual emancipation has freed itself temporarily from the domination of the superstitious,the crafty and the stupid; but even in the brightest of these periods the clouds of false civilisation have blinded truly great assassins to the august nature of tlmrdmts, and they are found spoiling some of their own greatest strokes by paying lip-service to the tenets of the mystagogues. Nevertheless encouragement can be found for the hope of a truly universal renaissance (if only the pragmatic sanctions for this art can be made clear to the well-disposed and ins true ted.persons everywhere) in the recurrence,by force of necessity or through individual genius,of natural assassins throughout every generation,persisting even to our benighted day. -

Anarchists in Social Work

ANARCHISTS IN SOCIAL WORK KNOWN TO THE AUTHORITIES Martin Gilbert ULVERSTON 1 Published by Martin S. Gilbert 4, Sandhall, Ulverston, Cumbria LA12 9EQ First published 2004 Second Edition 2005 Illustrations: Original drawings for Peter Good's contribution by Arthur Moyse Other illustrations by "Trott” (John Evans) ISBN: 0-9549159-0-9 Anarchists in Social Work: Known to the Authorities 1. Radical Social Work 2. Anarchist Perspective 3. Empirical Accounts 2 Anarchists in Social Work: Known To the Authorities CONTENTS Introduction and author profiles, Martin S Gilbert, Mark A Newns, Peter Good, John Evans, Doreen Frampton SRN 4 An Anarchist in Social Work, Martin S Gilbert 7 Anarchist Ideas in Action, Mark A Newns 33 Something Should Be Done, Peter Good 90 The Cycle of Deprivation, John Evans 126 Orpheus in the Underworld, John Evans 133 New Town Story, John Evans 140 Poetic Interlude 145 Whistle Blowing in the National Health Service, 146 Doreen Frampton, SRN Select Bibliography 148 Friends and Neighbours 149 3 INTRODUCTION This book contends that anarchist thought and action have at times positively informed professional social work. The introductory essay, by Martin Gilbert, outlines some ideas in the literature of radical social work, suggesting that the profession has had a radical tradition underlying its aspects of oppressive social control. Within that tradition, he contends that anarchists have made a significant, if hidden, contribution. Martin starts by mentioning some of this theory, progressing to record how libertarian ideas and methods of working helped him to organise groups; and networks in mental health services. Martin shows the stages of such development, its pitfalls, and what can be seen as repeatable results. -

Ullelit Piicllui

anarchistmmiveehly the oppressive nature of British capitalism. While the Special Branch spies UlLEliT PiiClLui on us, the SPG is l^t loose in the streets to finish their job, AUi/UT 10,000 anti-fascists marched 4th International, thus making arresting and repressing the peo- silently last Saturday afternoon political capital out of the vio- ple of this country who courage- (22.6.64) through the streets of lent death of an anti-fascist com- ously refuse to go down on their central London, in protest against rade. Nevertheless, this march w knees under the weight of exploit- the police brutality which made a was, because of the absence of the ation. As in any other authori- another victim in the person of usual empty slogans and blaring tarian regime, the British Estab- Kevin Gately, the 21-year old stu- megaphones, one of the most imp- lishment will use any powerful dent from Warwick University, ressive since the war. It ended method to smash people's will for killed as a result of a mounted in Hyde Park, where student and change, especially those pushing police charge in Bed Lion Square trade union leaders denounced the forward for a just, equitable and on Saturday 15th. brutal class nature of the Brit- free society. ish police, particularly the in- Let's make sure that Kevin We noticed with regret that the famous SPG (Special Patrol Groups) Gately did not fight and die in Trotskyist sections of the march which have been specially set up, va|n. Oppose racism and fascism, chose not to respect the National trained and used to smash pickets, the ultimate tools of capitalist Union of Students' call for a strikes, demos, squats and other rule. -

Scanned Image

paranoia by the anti-Fascist left - sink i.nto their deserved obscurity before the reality of two Woodford non-political, non-intellectual deaths. -J. J; -Jo anarchist fortnightly ‘P ‘P ‘P VOL.37 NO.11 29 MAY 1976 TWE LVE PENCE It is a thankless task to cloud with facts minds that are clear-cut with prejudicial theories, but for the record it must be done. The shortage of hous- ing and jobs which it is feared will come should restrictions on immigra- tion (even to the homecoming of British passport-holders) be relaxed has al- ways been the lot of workers under the capitalist (or state-capitalist) system. The arrival of immigrant workers, in COLOURED WORKERS at Bradford those who acted on the bloody instructi- any quantity or colour, is always ar- recently demonstrating (under their on so kindly handed out in the platitude. ranged when they are needed for speci- own steam) against the National Front Seeking for the approval of their elders, alist or sordid tasks. mocked (vide New Society) the Front's Paki-bashing, queer-bashing and drunk- cries of ‘Blacks Go Home‘ by chanting: rolling are only the words of ta conform- It was indeed Mr. Enoch Powell, he " ist and prejudiced society made into who is preserving us from the racialist LET'S GO BACK bruised and slashed flesh. ‘rivers of blood‘, who instituted the im-» --Who'll drive the buses ? portation of West Indians for necessary LET'S GO BACK These deaths at Woodford were the hospital tasks. All honour to him for --Who'll sweep the streets 2 product of hatred, not only racial hat- that -- it was necessary.