Islamic Resurgence in Bangladesh: Genesis, Dynamics and Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eating-In-Delhi

S No. Premises Name Premises Address District 1 DOMINOS PIZZA INDIA LTD GF, 18/27-E, EAST PATEL NAGAR, ND CENTRAL DISTRICT 2 STANDARD DHABA X-69 WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 3 KALA DA TEA & SNACKS 26/140, WEST PATEL NAGAR, NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 4 SHARON DI HATTI SHOP NO- 29, MALA MKT. WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW CENTRAL DISTRICT DELHI 5 MAA BHAGWATI RESTAURANT 3504, DARIBA PAN, DBG ROAD, DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 6 MITRA DA DHABA X-57, WEST PATEL NAGAR NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 7 CHICKEN HUT 3181, SANGTRASHAN STREET PAHAR GANJ, NEW CENTRAL DISTRICT DELHI 8 DIMPLE RESTAURANT 2105,D.B.GUPTA ROAD KAROL BAGH NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 9 MIGLANI DHABA 4240 GALI KRISHNA PAHAR GANJ, NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 10 DURGA SNACKS 813,G.F. KAMRA BANGASH DARYA GANJ NEW DELHI- CENTRAL DISTRICT 10002 11 M/S SHRI SHYAM CATERERS GF, SHOP NO 74-76A, MARUTI JAGGANATH NEAR CENTRAL DISTRICT KOTWALI, NEAR POLICE STATION, OPPOSITE TRAFFIC SIGNAL, DAR 12 AROMA SPICE 15A/61, WEA KAROL BAGH, NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 13 REPUBLIC OF CHICKEN 25/6, SHOP NO-4, GF, EAST PATEL NAGAR,DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 14 REHMATULLA DHABA 105/106/107/110 BAZAR MATIYA MAHAL, JAMA CENTRAL DISTRICT MASJID, DELHI 15 M/S LOCHIS CHIC BITES GF, SHOP NO 7724, PLOT NO 1, NEW MARKET KAROL CENTRAL DISTRICT BAGH, NEW DELHI 16 NEW MADHUR RESTAURANT 26/25-26 OLD RAJENDER NAGAR NEW DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 17 A B ENTERPRISES( 40 SEATS) 57/13,GF,OLD RAJINDER,NAGAR,DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 18 GRAND MADRAS CAFE GF,8301,GALI NO-4,MULTANI DHANDA PAHAR CENTRAL DISTRICT GANJ,DELHI-55 19 STANDARD SWEETS 3510,CHAWRI BAZAR,DELHI CENTRAL DISTRICT 20 M/S CAFE COFFEE DAY 3631, GROUND FLOOR, NETAJI SUBASH MARG, CENTRAL DISTRICT DARYAGANJ, NEW DELHI 21 CHANGEGI EATING HOUSE 3A EAST PARK RD KAROL BAGH ND DELHI 110055 CENTRAL DISTRICT 22 KAKE DA DHABA SHOP NO.47,OLD RAJINDER NAGAR,MARKET,NEW CENTRAL DISTRICT DELHI 23 CHOPRA DHABA 7A/5 WEA CHANNA MKT. -

United Nations Study on Violence Against Children Response to The

United Nations Study on Violence against Children Response to the questionnaire received from the Government of BANGLADESH QUESTIONNAIRE I. Legal Framework This part of the questionnaire aims to determine how your country's legal framework addresses violence against children, including prevention of violence, protection of children from violence, redress for victims of violence, penalties for perpetrators and reintegration and rehabilitation of victims. International human rights instruments 1. Describe any developments with respect to violence against children, which have resulted from your country's acceptance of international human rights instruments, including, for example, the convention of the Rights of the Child and its optional protocols, the Palermo Protocol or regional human rights instruments. Provide information on cases concerning violence against children in which your country's courts or tribunals have referred to international or regional human rights standards. Answer 1: The Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh was among the first country to ratify the United Nations Convention on the rights of the child (CRC) in 1990. As a signatory to the CRC and its protocol the Government of Bangladesh has made various efforts towards implementing the provision of the CRC. The Government has taken prompt action to disseminate the CRC to the stakeholder i.e. policy makers, elected public representatives at grass root level and to the civil society member to aware them about the right of the children. To implement the CRC the government had formed a core group after signing of the CRC and its optional protocol. The esteem Ministry is maintaining a database on violence against children of the country. -

Rhd Road Network, Rangpur Zone

RHD ROAD NETWORK, RANGPUR ZONE Banglabandha 5 N Tentulia Nijbari N 5 Z 5 0 6 Burimari 0 INDIA Patgram Panchagarh Z Mirgarh 5 9 0 Angorpota 3 1 0 0 5 Z Dhagram Bhaulaganj Chilahati Atwari Z 57 Z 06 5 0 Kolonihat Boda 2 1 Tunirhat Gomnati 3 0 Dhaldanga 7 Ruhea Z 5 N 6 5 Z 5 0 0 Dimla 0 0 2 3 7 9 2 5 6 Z 54 INDIA 5 Debiganj Z50 Sardarhat Z 9 5 0 5 5 Domar Hatibanda Bhurungamari Baliadangi Z N Kathuria Boragarihat Z5 Bahadur Dragha 002 2 Z5 0 7 0 03 5 Thakurgaon Z RLY 7 R 0 Station 58 2 7 7 Jaldhaka 2 5 Bus 6 Dharmagarh Stand Z 5 1 Z Z5 70 029 Z5 Nekmand Z Mogalhat 5 Kaliganj 6 Z5 Tengonmari 17 Nageshwari 2 7 56 4 7 Z 2 09 1 Raninagar Kadamtala 0 Z 0 0 57 5 9 0 Z 0 5 Phulbari Z 5 5 2 Z 5 5 Z Namorihat 0 Kalibari 2 Khansama 16 6 5 56 Z 2 Z Z Aditmari 01 Madarganj 50 Z5018 N509 Z59 4 Ranisonkail N5 08 Tebaria Nilphamari Kishoreganj 8 Z5 Kutubpur 00 008 Lalmonirhat Bhitarbond Z5 Z 2 Z5018 Z5018 Shaptibari 5 2 6 4 Darwani Z 2 6 0 1 0 5 Manthanahat 5 R Z5 Z 9 6 Z 0 00 Pirganj Bakultala 0 Barabari 5 2 5 5 5 1 0 Z Z Z Z5002 7 5 5 Z5002 Birganj 0 0 02 Gangachara N 5 0 5 Moshaldangi Z5020 06 6 06 0 5 0 N 5 Haragach Haripur Z 7 0 N5 Habumorh Bochaganj 0 5 4 Z 2 Z5 61 3 6 5 1 11 Z 5 Taraganj 2 6 Kurigram 0 N Hazirhat 5 Kaharol 5 Teesta 18 Z N5 Ranirbandar N5 Z Kaunia Bridge Rajarhat Z Saidpur Rangpur Shahebganj 5 Beldanga 0 Medical 0 5 Shapla 6 1 more 1 1 more 0 0 5 5 25 Ghagat Z 50 N517 Z Z Bridge Taxerhat N5 Mohiganj 1 2 Mordern 6 4 more 5 02 Z 8 5 Z Shampur 0 Modhupur Z 5 Parbatipur 50 N Sonapukur Badarganj 1 Chirirbandar Z5025 0 Ulipur Datbanga Govt Z5025 Pirgachha College R 5025 Simultala Laldangi 5 Z Kolahat Z 8 Kadamtali Biral Cantt. -

REMEMBERING PARTITION of BENGAL and the LIBERATION WAR of BANGLADESH SUBHAM HAZRA State Aided College Teacher, Dept

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.9.Issue 1. 2021 Impact Factor 6.8992 (ICI) http://www.rjelal.com; (Jan-Mar) Email:[email protected]:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE REMEMBERING PARTITION OF BENGAL AND THE LIBERATION WAR OF BANGLADESH SUBHAM HAZRA State Aided College Teacher, Dept. of English, Vivekananda Mahavidyalaya, Burdwan,West Bengal Abstract Memory and amnesia are always at the core of the relation between human beings and History. The interplay between past and present, memory and amnesia are always considered as a shape giver to investigate the earlier years of cataclysmic events. Partition is an empirical reality of human civilization. But how far it is possible to recreate that defunct memory of the horror and anxiety through a speculative Article Received:22/02/2021 narrative? Even if one embarks on this project can he bring forth something more Article Accepted: 29/03/2021 than an exhaustive history of the Liberation War. The partition of Bengal in 1947 and Published online:31/03/2021 the Bangladesh liberation war of 1971 are the major tumultuous episodes dismantled DOI: 10.33329/rjelal.9.1.251 the course of history –millions of people become homeless, abducted and decapitated by the name of religion and politicized nationalism. The cataclysmic events of partition is not a matter of contingency –one has to understand the political and religious agenda of Pakistani colonialism and the ‘localized’ narratives that led the liberation war of Bangladesh. It is rightly unjustful to target one specific religion to withhold the other. -

Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-Kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L

Western Washington University Western CEDAR A Collection of Open Access Books and Books and Monographs Monographs 2008 Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal David L. Curley Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Curley, David L., "Poetry and History: Bengali Maṅgal-kābya and Social Change in Precolonial Bengal" (2008). A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs. 5. https://cedar.wwu.edu/cedarbooks/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Books and Monographs at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in A Collection of Open Access Books and Monographs by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents Acknowledgements. 1. A Historian’s Introduction to Reading Mangal-Kabya. 2. Kings and Commerce on an Agrarian Frontier: Kalketu’s Story in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 3. Marriage, Honor, Agency, and Trials by Ordeal: Women’s Gender Roles in Candimangal. 4. ‘Tribute Exchange’ and the Liminality of Foreign Merchants in Mukunda’s Candimangal. 5. ‘Voluntary’ Relationships and Royal Gifts of Pan in Mughal Bengal. 6. Maharaja Krsnacandra, Hinduism and Kingship in the Contact Zone of Bengal. 7. Lost Meanings and New Stories: Candimangal after British Dominance. Index. Acknowledgements This collection of essays was made possible by the wonderful, multidisciplinary education in history and literature which I received at the University of Chicago. It is a pleasure to thank my living teachers, Herman Sinaiko, Ronald B. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Trans-boundary elected representative workshop on Challenges and Management of Public Disclosure Authorized Sundarbans Landscape: Finding a Shared Way Forward on Sundarbans On MV Paramhansa Cruise; 20 – 22 March, 2015 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1. Background ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2. Objectives of the event .................................................................................................................. 5 1.3. Scope of the event ......................................................................................................................... 6 2. Background for the event .............................................................................................................................. 6 2.1. Assessment of current situation .................................................................................................... 6 2.1.1. Key issues and challenges ............................................................................................................... 6 2.1.2. Current perception of key stakeholders ......................................................................................... 7 2.1.3. Possible problem solving approaches -

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE the COLONIAL CONTEXT: the BIRTH of BANGLADESH in Retrospectt

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE THE COLONIAL CONTEXT: THE BIRTH OF BANGLADESH IN RETROSPECTt By VedP. Nanda* I. INTRODUCTION In the aftermath of the Indo-Pakistan War in December 1971, the independent nation-state of Bangladesh was born.' Within the next four months, more than fifty countries had formally recognized the new nation.2 As India's military intervention was primarily responsible for the success of the secessionist movement in what was then known as East Pakistan, and for the creation of a new political entity on the inter- national scene,3 many serious questions stemming from this historic event remain unresolved for the international lawyer. For example: (1) What is the continuing validity of Article 2 (4) of the United Nations Charter?4 (2) What is the current status of the doctrine of humanita- rian intervention in international law?5 (3) What action could the United Nations have taken to avert the Bangladesh crisis?6 (4) What measures are necessary to prevent such tragic occurrences in the fu- ture?7 and (5) What relationship exists between the principle of self- "- This paper is an adapted version of a chapter that will appear in Y. ALEXANDER & R. FRIEDLANDER, SELF-DETERMINATION (1979). * Professor of Law and Director of the International Legal Studies Program, Univer- sity of Denver Law Center. 1. See generally BANGLADESH: CRISIS AND CONSEQUENCES (New Delhi: Deen Dayal Research Institute 1972); D. MANKEKAR, PAKISTAN CUT TO SIZE (1972); PAKISTAN POLITI- CAL SYSTEM IN CRISIS: EMERGENCE OF BANGLADESH (S. Varma & V. Narain eds. 1972). 2. Ebb Tide, THE ECONOMIST, April 8, 1972, at 47. -

Birth of Bangladesh: Down Memory Lane

Indian Foreign Affairs Journal Vol. 4, No. 3, July - September, 2009, 102-117 ORAL HISTORY Birth of Bangladesh: Down Memory Lane Arundhati Ghose, often acclaimed for espousing wittily India’s nuclear non- proliferation policy, narrates the events associated with an assignment during her early diplomatic career that culminated in the birth of a nation – Bangladesh. Indian Foreign Affairs Journal (IFAJ): Thank you, Ambassador, for agreeing to share your involvement and experiences on such an important event of world history. How do you view the entire episode, which is almost four decades old now? Arundhati Ghose (AG): It was a long time ago, and my memory of that time is a patchwork of incidents and impressions. In my recollection, it was like a wave. There was a lot of popular support in India for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his fight for the rights of the Bengalis of East Pakistan, fund-raising and so on. It was also a difficult period. The territory of what is now Bangladesh, was undergoing a kind of partition for the third time: the partition of Bengal in 1905, the partition of British India into India and Pakistan and now the partition of Pakistan. Though there are some writings on the last event, I feel that not enough research has been done in India on that. IFAJ: From India’s point of view, would you attribute the successful outcome of this event mainly to the military campaign or to diplomacy, or to the insights of the political leadership? AG: I would say it was all of these. -

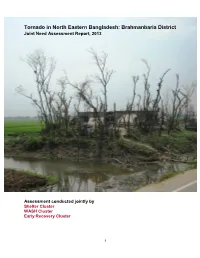

Brahmanbaria District Joint Need Assessment Report, 2013

Tornado in North Eastern Bangladesh: Brahmanbaria District Joint Need Assessment Report, 2013 Assessment conducted jointly by Shelter Cluster WASH Cluster Early Recovery Cluster 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary....................................................................................................... 6 Recommended Interventions......................................................................................... 8 Background.................................................................................................................... 10 Assessment Methodology.............................................................................................. 12 Key Findings.................................................................................................................. 14 Priorities identified by Upazila Officials.......................................................................... 18 Detailed Assessment Findings...................................................................................... 20 Shelter........................................................................................................................ 20 Water Sanitation & Hygiene....................................................................................... 20 Livelihoods.................................................................................................................. 21 Education.................................................................................................................... 24 -

Effectiveness of Depot-Holders Introduced in Urban Areas: Evidence from a Pilot in Bangladesh

J HEALTH POPUL NUTR 2005 Dec;23(4):377-387 © 2005 ICDDR,B: Centre for Health and Population Research ISSN 1606-0997 $ 5.00+0.20 Effectiveness of Depot-holders Introduced in Urban Areas: Evidence from a Pilot in Bangladesh Rukhsana Gazi, Alec Mercer, Jahanara Khatun, and Ziaul Islam Health Systems and Infectious Diseases Division ICDDR,B: Centre for Health and Population Research GPO Box 128, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh ABSTRACT Depot-holders are women from the community who promote good health practice and use of clinics. They keep a stock of contraceptives and oral rehydration salts to supply other women and are paid some incentives. In 2003, the NGO Service Delivery Program (NSDP) introduced depot-holders in three types of urban area in Bangladesh as a pilot. This evaluation study was carried out to: (a) establish a baseline for measuring the impact of activities of depot-holders on a comprehensive range of indicators in the long-term, (b) make a preliminary assessment of the impact on the use of selected services of the essen-tial services package (ESP) and other indicators at the end of the pilot phase, and (c) assess the cost of introducing depot-holders and running their activities for a year. Data from the baseline and end of pilot household surveys, together with service statistics from the intervention and comparison areas, were used for assessing the changes in clinic use and commodity distribution. The study found evidence that the depot-holders transferred knowledge to women in the community, provided services, and referred women to clinics run by non-governmental organizations (NGOs). -

Bangladesh – Hindus – Awami League – Bengali Language

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: BGD30821 Country: Bangladesh Date: 8 November 2006 Keywords: Bangladesh – Hindus – Awami League – Bengali language This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Are Hindus a minority religion in Bangladesh? 2. How are religious minorities, notably Hindus, treated in Bangladesh? 3. Is the Awami League traditionally supported by the Hindus in Bangladesh? 4. Are Hindu supporters of the Awami League discriminated against and if so, by whom? 5. Are there parts of Bangladesh where Hindus enjoy more safety? 6. Is Bengali the language of Bangladeshis? RESPONSE 1. Are Hindus a minority religion in Bangladesh? Hindus constitute approximately 10 percent of the population in Bangladesh making them a religious minority. Sunni Muslims constitute around 88 percent of the population and Buddhists and Christians make up the remainder of the religious minorities. The Hindu minority in Bangladesh has progressively diminished since partition in 1947 from approximately 25 percent of the population to its current 10 percent (US Department of State 2006, International Religious Freedom Report for 2006 – Bangladesh, 15 September – Attachment 1). 2. How are religious minorities, notably Hindus, treated in Bangladesh? In general, minorities in Bangladesh have been consistently mistreated by the government and Islamist extremists. Specific discrimination against the Hindu minority intensified immediately following the 2001 national elections when the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) gained victory with its four-party coalition government, including two Islamic parties. -

King for a Day Teacher's Guide

King for a Day Teacher’s Guide for Grades K - 3 With Student Activity Sheets by Rukhsana Khan www.rukhsanakhan.com About Rukhsana Khan Rukhsana has been writing seriously since 1989. Currently she has twelve books published, several of which have been nominated and/or won awards. She is an accomplished storyteller and has performed at numerous festivals. For more information on Rukhsana and her books please visit her website: www.rukhsanakhan.com Rukhsana was born in Lahore, Pakistan and immigrated to Canada, with her family, at the age of three. She began by writing for community magazines and went on to write songs and stories for the Adam's World children's videos. Rukhsana is a member of SCBWI, The Writers Union of Canada and Storytelling Toronto. She lives in Toronto with her husband and family. To see the video book talk/tutorials for King for a Day and other titles, check out Ru khsana‘s Youtube chann el Books by Rukhsana: https://www.youtube.com/user/MsRukhsanaKhan King for a Day Big Red Lollipop Wanting Mor A New Life Many Windows Silly Chicken Ruler of the Courtyard The Roses in My Carpets Muslim Child King of the Skies Bedtime Ba-a-a-lk Dahling if You Luv Me Would You Please Please Smile King for a Day Teacher’s Guide by Rukhsana Khan Page 2 The following curriculum applications are fulfilled by the discussion topics and activities outlined in this teacher’s guide: Legend writing applications character applications visual art math applications applications drama applications Social Studies For insights into the creation of this book, read the interview between the author Rukhsana Khan and the illustrator Christiane Kromer in Appendix 1 Discussion Topics before reading the book (Reading Standards, Integration of Knowledge & Ideas, Strand 7) (Speaking & Listening Standards, Comprehension & Collaboration, Strands 1 and 2) Grades K - 3: Examine the cover of King for a Day.