Effectiveness of Depot-Holders Introduced in Urban Areas: Evidence from a Pilot in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brahmanbaria District Joint Need Assessment Report, 2013

Tornado in North Eastern Bangladesh: Brahmanbaria District Joint Need Assessment Report, 2013 Assessment conducted jointly by Shelter Cluster WASH Cluster Early Recovery Cluster 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary....................................................................................................... 6 Recommended Interventions......................................................................................... 8 Background.................................................................................................................... 10 Assessment Methodology.............................................................................................. 12 Key Findings.................................................................................................................. 14 Priorities identified by Upazila Officials.......................................................................... 18 Detailed Assessment Findings...................................................................................... 20 Shelter........................................................................................................................ 20 Water Sanitation & Hygiene....................................................................................... 20 Livelihoods.................................................................................................................. 21 Education.................................................................................................................... 24 -

Bangladesh – Hindus – Awami League – Bengali Language

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: BGD30821 Country: Bangladesh Date: 8 November 2006 Keywords: Bangladesh – Hindus – Awami League – Bengali language This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Are Hindus a minority religion in Bangladesh? 2. How are religious minorities, notably Hindus, treated in Bangladesh? 3. Is the Awami League traditionally supported by the Hindus in Bangladesh? 4. Are Hindu supporters of the Awami League discriminated against and if so, by whom? 5. Are there parts of Bangladesh where Hindus enjoy more safety? 6. Is Bengali the language of Bangladeshis? RESPONSE 1. Are Hindus a minority religion in Bangladesh? Hindus constitute approximately 10 percent of the population in Bangladesh making them a religious minority. Sunni Muslims constitute around 88 percent of the population and Buddhists and Christians make up the remainder of the religious minorities. The Hindu minority in Bangladesh has progressively diminished since partition in 1947 from approximately 25 percent of the population to its current 10 percent (US Department of State 2006, International Religious Freedom Report for 2006 – Bangladesh, 15 September – Attachment 1). 2. How are religious minorities, notably Hindus, treated in Bangladesh? In general, minorities in Bangladesh have been consistently mistreated by the government and Islamist extremists. Specific discrimination against the Hindu minority intensified immediately following the 2001 national elections when the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) gained victory with its four-party coalition government, including two Islamic parties. -

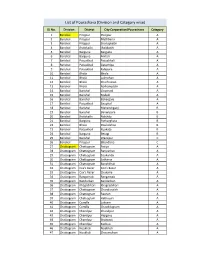

List of Pourashava (Division and Category Wise)

List of Pourashava (Division and Category wise) SL No. Division District City Corporation/Pourashava Category 1 Barishal Pirojpur Pirojpur A 2 Barishal Pirojpur Mathbaria A 3 Barishal Pirojpur Shorupkathi A 4 Barishal Jhalokathi Jhalakathi A 5 Barishal Barguna Barguna A 6 Barishal Barguna Amtali A 7 Barishal Patuakhali Patuakhali A 8 Barishal Patuakhali Galachipa A 9 Barishal Patuakhali Kalapara A 10 Barishal Bhola Bhola A 11 Barishal Bhola Lalmohan A 12 Barishal Bhola Charfession A 13 Barishal Bhola Borhanuddin A 14 Barishal Barishal Gournadi A 15 Barishal Barishal Muladi A 16 Barishal Barishal Bakerganj A 17 Barishal Patuakhali Bauphal A 18 Barishal Barishal Mehendiganj B 19 Barishal Barishal Banaripara B 20 Barishal Jhalokathi Nalchity B 21 Barishal Barguna Patharghata B 22 Barishal Bhola Doulatkhan B 23 Barishal Patuakhali Kuakata B 24 Barishal Barguna Betagi B 25 Barishal Barishal Wazirpur C 26 Barishal Pirojpur Bhandaria C 27 Chattogram Chattogram Patiya A 28 Chattogram Chattogram Bariyarhat A 29 Chattogram Chattogram Sitakunda A 30 Chattogram Chattogram Satkania A 31 Chattogram Chattogram Banshkhali A 32 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Cox’s Bazar A 33 Chattogram Cox's Bazar Chakaria A 34 Chattogram Rangamati Rangamati A 35 Chattogram Bandarban Bandarban A 36 Chattogram Khagrchhari Khagrachhari A 37 Chattogram Chattogram Chandanaish A 38 Chattogram Chattogram Raozan A 39 Chattogram Chattogram Hathazari A 40 Chattogram Cumilla Laksam A 41 Chattogram Cumilla Chauddagram A 42 Chattogram Chandpur Chandpur A 43 Chattogram Chandpur Hajiganj A -

127 Branches

মেটলাইফ পলললির প্রিপ্রিয়াি ও অꇍযাꇍয মপমেন্ট বযা廬ক এপ্রিয়ার িকল শাখায় ꇍগদে প্রদান কমর তাৎক্ষপ্রিকভাদব বমু ে লনন ররপ্রভপ্রꇍউ স্ট্যাম্প ও সীলসহ রিটলাইদের প্ররপ্রসট এই িলু বধা পাওয়ার জনয গ্রাহকমক মকান অলিলরক্ত লফ অথবা স্ট্যাম্প চাজ জ প্রদান করমি হমব না Sl. No. Division District Name of Branches Address of Branch 1 Barisal Barisal Barishal Branch Fakir Complex 112 Birshrashtra Captain Mohiuddin Jahangir Sarak 2 Barisal Bhola Bhola Branch Nabaroon Center(1st Floor), Sadar Road, Bhola 3 Chittagong Chittagong Agrabad Branch 69, Agrabad C/ A, Chittagong 4 Chittagong Chittagong Anderkilla Branch 184, J.M Sen Avenue Anderkilla 5 Chittagong Chittagong Bahadderhat Branch Mamtaz Tower 4540, Bahadderhat 6 Chittagong Chittagong Bank Asia Bhaban Branch 39 Agrabad C/A Manoda Mansion (2nd Floor), Holding No.319, Ward No.3, College 7 Chittagong Comilla Barura Branch Road, Barura Bazar, Upazilla: Barura, District: Comilla. 8 Chittagong Chittagong Bhatiary Branch Bhatiary, Shitakunda 9 Chittagong Brahmanbaria Brahmanbaria Branch "Muktijoddha Complex Bhaban" 1061, Sadar Hospital Road 10 Chittagong Chittagong C.D.A. Avenue Branch 665 CDA Avenue, East Nasirabad 1676/G/1 River City Market (1st Floor), Shah Amant Bridge 11 Chittagong Chaktai Chaktai Branch connecting road 12 Chittagong Chandpur Chandpur Branch Appollo Pal Bazar Shopping, Mizanur Rahman Road 13 Chittagong Lakshmipur Chandragonj Branch 39 Sharif Plaza, Maddho Bazar, Chandragonj, Lakshimpur 14 Chittagong Noakhali Chatkhil Branch Holding No. 3147 Khilpara Road Chatkhil Bazar Chatkhil 15 Chittagong Comilla Comilla Branch Chowdhury Plaza 2, House- 465/401, Race Course 16 Chittagong Comilla Companigonj Branch Hazi Shamsul Hoque Market, Companygonj, Muradnagar J.N. -

BRAHMANBARIA District

GEO Code based Unique Water Point ID Brahmanbaria District Department of Public Health Engineering (DPHE) June, 2018 How to Use This Booklet to Assign Water Point Identification Code: Assuming that a contractor or a driller is to install a Shallow Tube Well with No. 6 Pump in SULTANPUR village BEMARTA union of BAGERHAT SADAR uapzila in BAGERHAR district. This water point will be installed in year 2010 by a GOB-Unicef project. The site of installation is a bazaar. The steps to assign water point code (Figure 1) are as follows: Y Y Y Y R O O W W Z Z T T U U U V V V N N N Figure 1: Format of Geocode Based Water Point Identification Code Step 1: Write water point year of installation as the first 4 digits indicated by YYYY. For this example, it is 2010. Step 2: Select land use type (R) code from Table R (page no. 4). For this example, a bazaar for rural commercial purpose, so it is 4. Step 3: Select water point type of ownership (OO) from Table OO (page no. 4) . For this example, it is 05. Step 4: Select water point type (WW) code from Table WW (page no. 5). For this example, water point type is Shallow Tube Well with No. 6 Pump. Therefore its code is 01. Step 5: Assign district (ZZ), upazila (TT) and union (UUU) GEO Code for water point. The GEO codes are as follows: for BAGERGAT district, ZZ is 01; for BAGERHAR SADAR upazila, TT is 08; and for BEMARTA union, UUU is 151. -

Traditional Institutions As Tools of Political Islam in Bangladesh

01_riaz_055072 (jk-t) 15/6/05 11:43 am Page 171 Traditional Institutions as Tools of Political Islam in Bangladesh Ali Riaz Illinois State University, USA ABSTRACT Since 1991, salish (village arbitration) and fatwa (religious edict) have become common features of Bangladesh society, especially in rural areas. Women and non-governmental development organizations (NGOs) have been subjected to fatwas delivered through a traditional social institution called salish. This article examines this phenomenon and its relationship to the rise of Islam as political ideology and increasing strengths of Islamist parties in Bangladesh. This article challenges existing interpretations that persecution of women through salish and fatwa is a reaction of the rural community against the modernization process; that fatwas represent an important tool in the backlash of traditional elites against the impoverished rural women; and that the actions of the rural mullahs do not have any political links. The article shows, with several case studies, that use of salish and fatwa as tools of subjection of women and development organizations reflect an effort to utilize traditional local institutions to further particular interpretations of behavior and of the rights of indi- viduals under Islam, and that this interpretation is intrinsically linked to the Islamists’ agenda. Keywords: Bangladesh; fatwa; political Islam Introduction Although the alarming rise of the militant Islamists in Bangladesh and their menacing acts in the rural areas have received international media attention in recent days (e.g. Griswold, 2005), the process began more than a decade ago. The policies of the authoritarian military regimes that ruled Bangladesh between 1975 and 1990, and the politics of expediency of the two major politi- cal parties – the Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) – enabled the Islamists to emerge from the political wilderness to a legit- imate political force in the national arena (Riaz, 2003). -

A Case Study of Brahmanaria Tornado Mdrezwan Siddiqui* and Taslima Hossain* Department of Geography and Environment, University of Dhaka, Yunus Centre, Thailand

aphy & N r at og u e ra G l Siddiqui and Hossain, J Geogr Nat Disast 2013, 3:2 f D o i s l a Journal of a s DOI: 10.4172/2167-0587.1000111 n t r e u r s o J ISSN: 2167-0587 Geography & Natural Disasters ResearchCase Report Article OpenOpen Access Access Geographical Characteristics and the Components at Risk of Tornado in Rural Bangladesh: A Case Study of Brahmanaria Tornado MdRezwan Siddiqui* and Taslima Hossain* Department of Geography and Environment, University of Dhaka, Yunus Centre, Thailand Abstract On 22 March 2013, a tornado swept over the Brahmanaria and Akhura Sadar Upazila (sub-district) of Brahmanaria district in Chittagong Division of Bangladesh and caused 35 deaths. There were also high levels of property damages. The aim of this paper is to present the geographical characteristics of Brahmanaria tornado and the detail of damages it has done. Through this we will assess the components at risk of tornado in the context of rural Bangladesh. Research shows that, though small in nature and size, Brahmanaria tornado was very much catastrophic – mainly due to the lack of awareness about this natural phenomenon. This tornado lasts for about 15 minutes and traveled a distance of 12 kilometer with an area of influence of 1 square kilometer of area. Poor and unplanned construction of houses and other infrastructures was also responsible for 35 deaths, as these constructions were unable to give any kind of protection during tornado. From this research, it has been seen that human life, poultry and livestock are mostly at risk of tornadoes in case of rural Bangladesh. -

Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 10 04 10 04

Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 BARISAL DIVISION 10 04 BARGUNA 10 04 09 AMTALI 10 04 19 BAMNA 10 04 28 BARGUNA SADAR 10 04 47 BETAGI 10 04 85 PATHARGHATA 10 04 92 TALTALI 10 06 BARISAL 10 06 02 AGAILJHARA 10 06 03 BABUGANJ 10 06 07 BAKERGANJ 10 06 10 BANARI PARA 10 06 32 GAURNADI 10 06 36 HIZLA 10 06 51 BARISAL SADAR (KOTWALI) 10 06 62 MHENDIGANJ 10 06 69 MULADI 10 06 94 WAZIRPUR 10 09 BHOLA 10 09 18 BHOLA SADAR 10 09 21 BURHANUDDIN 10 09 25 CHAR FASSON 10 09 29 DAULAT KHAN 10 09 54 LALMOHAN 10 09 65 MANPURA 10 09 91 TAZUMUDDIN 10 42 JHALOKATI 10 42 40 JHALOKATI SADAR 10 42 43 KANTHALIA 10 42 73 NALCHITY 10 42 84 RAJAPUR 10 78 PATUAKHALI 10 78 38 BAUPHAL 10 78 52 DASHMINA 10 78 55 DUMKI 10 78 57 GALACHIPA 10 78 66 KALAPARA 10 78 76 MIRZAGANJ 10 78 95 PATUAKHALI SADAR 10 78 97 RANGABALI Geo Code list (upto upazila) of Bangladesh As On March, 2013 Division Zila Upazila Name of Upazila/Thana 10 79 PIROJPUR 10 79 14 BHANDARIA 10 79 47 KAWKHALI 10 79 58 MATHBARIA 10 79 76 NAZIRPUR 10 79 80 PIROJPUR SADAR 10 79 87 NESARABAD (SWARUPKATI) 10 79 90 ZIANAGAR 20 CHITTAGONG DIVISION 20 03 BANDARBAN 20 03 04 ALIKADAM 20 03 14 BANDARBAN SADAR 20 03 51 LAMA 20 03 73 NAIKHONGCHHARI 20 03 89 ROWANGCHHARI 20 03 91 RUMA 20 03 95 THANCHI 20 12 BRAHMANBARIA 20 12 02 AKHAURA 20 12 04 BANCHHARAMPUR 20 12 07 BIJOYNAGAR 20 12 13 BRAHMANBARIA SADAR 20 12 33 ASHUGANJ 20 12 63 KASBA 20 12 85 NABINAGAR 20 12 90 NASIRNAGAR 20 12 94 SARAIL 20 13 CHANDPUR 20 13 22 CHANDPUR SADAR 20 13 45 FARIDGANJ -

Under Threat: the Challenges Facing Religious Minorities in Bangladesh Hindu Women Line up to Vote in Elections in Dhaka, Bangladesh

report Under threat: The challenges facing religious minorities in Bangladesh Hindu women line up to vote in elections in Dhaka, Bangladesh. REUTERS/Mohammad Shahisullah Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International This report has been produced with the assistance of the Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency. non-governmental organization (NGO) working to secure The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the rights of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and Minority Rights Group International, and can in no way be indigenous peoples worldwide, and to promote cooperation taken to reflect the views of the Swedish International and understanding between communities. Our activities are Development Cooperation Agency. focused on international advocacy, training, publishing and outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by our worldwide partner network of organizations, which represent minority and indigenous peoples. MRG works with over 150 organizations in nearly 50 countries. Our governing Council, which meets twice a year, has members from 10 different countries. MRG has consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Minority Rights Group International would like to thank Social Council (ECOSOC), and observer status with the Human Rights Alliance Bangladesh for their general support African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights in producing this report. Thank you also to Bangladesh (ACHPR). MRG is registered as a charity and a company Centre for Human Rights and Development, Bangladesh limited by guarantee under English law: registered charity Minority Watch, and the Kapaeeng Foundation for supporting no. 282305, limited company no. 1544957. the documentation of violations against minorities. -

Violence Originated from Facebook: a Case Study in Bangladesh

Violence originated from Facebook: A case study in Bangladesh Matiur Rahman Minar Jibon Naher Department of Computer Science and Engineering Department of Computer Science and Engineering Chittagong University of Engineering and Technology Chittagong University of Engineering and Technology Chittagong-4349, Bangladesh Chittagong-4349, Bangladesh [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Facebook as in social network is a great innovation We are going to discuss the incidents in section II. In section of modern times. Among all social networking sites, Facebook is III, we will analyze the cases, discuss the similarities and the the most popular social network all over the world. Bangladesh is links with social network i.e. Facebook. Section IV is about no exception. People use Facebook for various reasons e.g. social networking and communication, online shopping and business, some possible recommendations about how we can prevent knowledge and experience sharing etc. However, some recent these kind of violence from technology perspectives. incidents in Bangladesh, originated from or based on Facebook activities, led to arson and violence. Social network i.e. Facebook II. CASE OVERVIEW was used in these incidents mostly as a tool to trigger hatred In recent 5-6 years, quite a number of incidents happened, and violence. This case study discusses these technology related incidents and recommends possible future measurements to where Facebook was the trigger to initiate the violent situ- prevent such violence. ations. We are going to discuss these cases in descending Index Terms—Human-computer interaction, Social network, manner, starting from the latest. Relevant pictures of these Facebook, Technology misuse, Violence, Bangladesh violence are added, which are collected from referenced news articles. -

Digital Disinformation and Communalism in Bangladesh

China Media Research, 15(2), 2019 ISSN: 1556-889X Digital Disinformation and Communalism in Bangladesh Md. Sayeed Al-Zaman Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh Abstract: Traditional society of Bangladesh has been enduring explicit transformation. Individuals’ increasing income, flourishing consumer culture, and security in social life as a cumulative force smooths the scope of modern global amenities to come in and grow up amid this changing society. Of them, new age digital communication is vital one. Digital media is encompassing people’s everyday life. Process of acquiring information has also changed remarkably: instead of searching to get one, people now struggle to look for reliable information due to ample information. Cyberspace becomes the cornucopia of fluid information that often baffles the surfers by providing distorted information. Bangladesh has been experiencing digital media-initiated disinformation from the beginning of 2010s. Interest groups are playing with digital disinformation conjoining religious sentiment. As a result, incidents of assault on religious minorities based on digital (dis)information have become frequent. Considering the importance of digital disinformation instigating communalism in Bangladesh, this study explores the nature of contemporary digital communalism and violence on religious minorities. It has been seen that beyond mere religious sentimentalism and sensationalism, historical and political along with several other factors significantly contribute to these atrocities. Keywords: disinformation, religion, communal violence, social media, digital communalism, minority [Md. Sayeed Al-Zaman. Digital Disinformation and Communalism in Bangladesh. China Media Research, 15(2):68-76] Introduction number of digital media user is large enough, and the In October 2017, Israeli police mistakenly arrested a growth is continuing; (b) beyond mainstream media, Palestinian construction worker after the Artificial digital media works as a primary source of Intelligence (AI) of Facebook mistranslated a post. -

Ecology of Shakla Beel (Brahmanbaria), Bangladesh

Bangladesh f Fish. Res.,8(2), 2004: 101-lll ©BFRI Ecology of Shakla heel (Brahmanbaria), Bangladesh K.K.U. Ahmed, K.R. Hasan, S.U. Ahamed, T. Ahmed and G. Mustafa1 Bangladesh Fisheries Research Institute, Riverine Station, Chandpur 3602, Bangladesh 1WorldFish Center-Bangladesh, House# 22, Road-7, Block-F, Banani, Dhaka Absrracu: The bed Shakla, comprising an average area of 75.0 ha is located in the northeastern region (Brahmanbaria district) of Bangladesh. The study was carried out to assess the ecological aspects of bed ecosystem. Surface run-off and increase inflow of rain water from the upper stretch during monsoon cause inundation and resumption of connection between beel and parent rivers. The range of dissolved oxygen (DO) content ( 4.5-8.9 mg/L) was found congenial for aquatic life. pH was in the alkaline range (7.3-8.5) and free C02 was reletavely high. Lower values of total hardness and total alkalinity indicated less nutrients in the beel water. A wide variation (1.4-27.2 x 103 ceHs/L) in the standing crop of total plankton was recorded during study period of which phytoplankton alone contributed about 90%. Phytoplankton diversity in the beel represented by three groups viz. Chlorophyceae, Myxophyceae and Bacillariophyceae in order of abundance. A total of 52 fish species belonging to 36 genera, 20 families and 1 species of prawn were identified so far from the beel. About l3 types of fishing method were found in operation. Seine nets (moshari berja~ ghono berjal) and gill net (current jal) were identified as detrimental gear killing juveniles of different species during post spawning period.