Group B Expulsions of Jews and Muslims from Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Culture in the Christian World James Jefferson White University of New Mexico - Main Campus

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 11-13-2017 Jewish Culture in the Christian World James Jefferson White University of New Mexico - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation White, James Jefferson. "Jewish Culture in the Christian World." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/207 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. James J White Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Sarah Davis-Secord, Chairperson Timothy Graham Michael Ryan i JEWISH CULTURE IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD by JAMES J WHITE PREVIOUS DEGREES BACHELORS THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2017 ii JEWISH CULTURE IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD BY James White B.S., History, University of North Texas, 2013 M.A., History, University of New Mexico, 2017 ABSTRACT Christians constantly borrowed the culture of their Jewish neighbors and adapted it to Christianity. This adoption and appropriation of Jewish culture can be fit into three phases. The first phase regarded Jewish religion and philosophy. From the eighth century to the thirteenth century, Christians borrowed Jewish religious exegesis and beliefs in order to expand their own understanding of Christian religious texts. -

Shulchan Arukh Amy Milligan Old Dominion University, [email protected]

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Women's Studies Faculty Publications Women’s Studies 2010 Shulchan Arukh Amy Milligan Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/womensstudies_fac_pubs Part of the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Yiddish Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Milligan, Amy, "Shulchan Arukh" (2010). Women's Studies Faculty Publications. 10. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/womensstudies_fac_pubs/10 Original Publication Citation Milligan, A. (2010). Shulchan Arukh. In D. M. Fahey (Ed.), Milestone documents in world religions: Exploring traditions of faith through primary sources (Vol. 2, pp. 958-971). Dallas: Schlager Group:. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Women’s Studies at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spanish Jews taking refuge in the Atlas Mountains in the fifteenth century (Spanish Jews taking refuge in the Atlas Mountains, illustration by Michelet c.1900 (colour litho), Bombled, Louis (1862-1927) / Private Collection / Archives Charmet / The Bridgeman Art Library International) 958 Milestone Documents of World Religions Shulchan Arukh 1570 ca. “A person should dress differently than he does on weekdays so he will remember that it is the Sabbath.” Overview Arukh continues to serve as a guide in the fast-paced con- temporary world. The Shulchan Arukh, literally translated as “The Set Table,” is a compilation of Jew- Context ish legal codes. -

Traveling with Jewish Taste We're Off on the Road to Morocco – Culinarily, at Least by Carol Goodman Kaufman

Page 16 Berkshire Jewish Voice • jewishberkshires.org July 27 to September 6, 2020 BERKSHIRE JEWISH VOICES Traveling with Jewish Taste We're off on the Road to Morocco – culinarily, at least By Carol Goodman Kaufman As anyone who reads this column regularly may guess, I love to travel. And, much of what I love about traveling to points around the globe is sampling the amazing variety of native foods and flavors. So, since we can’t really visit places much farther than a gas tank’s capacity right now, why not do it in our kitchens? And, while we’re imagining our tour, why not “meet” some members of the Tribe. Let’s start our global trek in Morocco. Jews have been present in Morocco for two and a half millennia, tolerated under heavy taxation in the best of times, persecuted and executed during the worst. The first recorded presence of Jews in Morocco was in the 8th century under Carthaginian rule. Their numbers grew between the 8th and 12th centuries, and Slat Al Azama Synagogue in Marrakech Fez was a particularly attractive destination due to its diverse and tolerant popu- lation. A golden age for Fez Jews lasted for almost three hundred years. The next couple of centuries saw a somewhat tolerant Almoravid rule, although Jews lived under Moroccan Braised Chicken With Dates dhimmi status, meaning “protected person.” As Serves 6 non-Muslims, they were required to pay special taxes If there is one food that conjures up images of camel caravans, desert oases, in exchange for being able to fragrant spices, and coffee boiling over an open fire, it is the date. -

The Legacy of the Inquisition in the Colonization of New Spain and New Mexico C

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Student Papers (History) Department of History 5-11-2012 Lobos y Perros Rabiosos: The Legacy of the Inquisition in the Colonization of New Spain and New Mexico C. Michael Torres [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.utep.edu/hist_honors Comments: Master's Seminar Essay Recommended Citation Torres, C. Michael, "Lobos y Perros Rabiosos: The Legacy of the Inquisition in the Colonization of New Spain and New Mexico" (2012). Student Papers (History). Paper 2. http://digitalcommons.utep.edu/hist_honors/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Papers (History) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOBOS Y PERROS RABIOSOS: The Legacy of the Inquisition in the Colonization of New Spain and New Mexico Cheryl Martin, PhD. Master’s Seminar Essay May 11, 2012 C. Michael Torres 1 It is unlikely that any American elementary school student could forget the importance of the year 1492, as it immediately brings to mind explorer Christopher Columbus, his three tiny sailing ships and the daring voyage of discovery to the New World. Of no less importance was what historian Teofilo Ruiz of UCLA has called the Other 1492, the completion of the Reconquista (Reconquest) of the Moorish kingdoms in Iberia, and the expulsion of the Jews from Spain by the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragón, and Queen Isabella of Castile.1 These seemingly unconnected events influenced the history and economy of Spain and Europe, setting in motion the exploration, immigration, and colonization of the Americas which gave rise to Spain‟s Golden Age. -

1492 Reconsidered: Religious and Social Change in Fifteenth Century Ávila

1492 RECONSIDERED: RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN FIFTEENTH CENTURY ÁVILA by Carolyn Salomons A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland May 2014 © 2014 Carolyn Salomons All Rights Reserved Abstract This dissertation is an assessment of the impact of the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 on the city of Ávila, in northwestern Castile. The expulsion was the culmination of a series of policies set forth by Isabel I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon regarding Jewish-Christian relations. The monarchs invoked these policies in order to bolster the faith and religious praxis of Catholics in the kingdoms, especially those Catholics newly converted from Judaism. My work shows how the implementation of these strategies began to fracture the heretofore relatively convivial relations between the confessional groups residing in Ávila. A key component of the Crown’s policies was the creation of a Jewish quarter in the city, where previously, Jews had lived wherever they chose. This transformation of a previously shared civic place to one demarcated clearly by religious affiliation, i.e. the creation of both Jewish and Christian space, had a visceral impact on how Christians related to their former neighbors, and hostilities between the two communities increased in the closing decades of the fifteenth century. Yet at the same time, Jewish appeals to the Crown for assistance in the face of harassment and persecution were almost always answered positively, with the Crown intervening several times on behalf of their Jewish subjects. This seemingly incongruous attitude reveals a key component in the relationship between the Crown and Jews: the “royal alliance.” My work also details how invoking that alliance came at the expense of the horizontal alliances between Abulense Jews and Christians, and only fostered antagonism between the confessional groups. -

Sephardi Zionism in Hamidian Jerusalem

“The Spirit of Love for our Holy Land:” Sephardi Zionism in Hamidian Jerusalem Ari Shapiro Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, Georgetown University Advisor: Professor Aviel Roshwald Honors Program Chair: Professor Katherine Benton-Cohen May 7, 2018 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 2 Important Dates 3 Introduction 4 Chapter 1: Sephardi Identity in Context (5600-5668/1840-1908) 11 Sephardi Identity Among Palestinian Arabs 15 Sephardi Identity under the Ottoman Administration of Palestine 19 Chapter 2: Distinctly Sephardic Zionism (5640-5656/1880-1896) 23 Kol Yisra’el Ḥaverim and the New Sephardi Leadership 27 Land Purchase Through International Sephardi Networks 32 Land Purchase as a Religious Obligation 36 Chapter 3: Arab and Ottoman Influence on the Development of Sephardi Zionism (5646-5668/1886-1908) 43 Shifting Ottoman Boundaries and Jerusalem’s Political Ascent 45 European Liberalism, Ottoman Reform, and Sephardi Zionism 50 Sephardi Zionism as a Response to Hamidian Ottomanism 54 Chapter 4: The Decline of Sephardi Zionism in Jerusalem (5658-5668/1897-1908) 62 Aliyah, Jewish Demographics, and the Ashkenazi Ascent in Palestine 63 Palestinian Arab Opposition to Zionist Activity in Jerusalem 69 The Young Turk Revolt and the Death of Sephardi Zionism 73 Conclusion 79 Appendix 84 Glossary of Persons 85 Glossary of Terms 86 Bibliography 89 2 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the network of family, friends, peers, and mentors who have helped me get to this point. To my parents and Esti, thanks for being such interested sounding boards for new lines of exploration at any and all hours when I call. -

Spain's Offer to Sephardic Jews to 'Come Home' May Come with Costly Strings and Red Tape Attached Europe World the Independent

5/10/2015 Spain's offer to Sephardic Jews to 'come home' may come with costly strings and red tape attached Europe World The Independent THE INDEPENDENT SUNDAY 10 MAY 2015 Apps eBooks i Jobs Dating Shop Sign in Register NEWS VIDEO PEOPLE VOICES SPORT TECH LIFE PROPERTY ARTS + ENTS TRAVEL MONEY INDYBEST STUDENT OFFERS UK World Business People Science Environment Media Technology Education Images Obituaries Diary Corrections Newsletter Appeals News > World > Europe Spain's offer to Sephardic Jews to 'come home' may come with costly strings and red tape attached Search The Independent Advanced search Article archive Topics UK ELECTION RESULT All seats declared MAJORITY 326 331 Conservative 232 Labour 56 SNP 8 Liberal Democrat 1 UKIP 3 Plaid Cymru 8 DUP 4 Sinn Fein 3 SDLP 4 Other Source: Electoral Commission © GRAPHIC NEWS The application procedure for ʹreturningʹ Sephardic Jews has been criticised for cost and complication, and for the possible inclusion of a general knowledge test on Spainʹs constitution ALASDAIR FOTHERINGHAM BARCELONA Tuesday 05 May 2015 Shares: 385 PRINT A A A PEOPLE When it was confirmed that the descendants of a Jewish community exiled from Spain more than 500 years ago would be granted legal rights to apply for Spanish citizenship, Batsheba Chevalier Sola and Jose Romero Caballero, who run Granada’s 1 Naz Shah: Here's what the tiny but thriving Jewish information centre, were quietly woman who defeated George JK Rowling shuts contented with the news. Now, however, they – and others – are Galloway plans to do next down anti-Labour not so sure. Twitter trolls 2 These are the contenders for In medieval times, Granada was one of Spain’s most important the next Lib Dem leader VOICES Jewish centres. -

DNA Evidence Suggests Many Lowland Scots and Northern Irish Have Jewish Ancestry

IOSR Journal of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 26, Issue 6, Series 10 (June. 2021) 22-42 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org DNA Evidence Suggests Many Lowland Scots And Northern Irish Have Jewish Ancestry. Elizabeth C. Hirschman Hill Richmond Gott Professor of Business Department of Business and Economics University of Virginia-Wise Abstract: This study uses the newest genealogical DNA methodology of phylogenetic trees to identify a large population of Jewish descent in the Scottish Lowlands and Northern Ireland. It is proposed that the majority of these Lowland Scots and Northern Ireland colonists were likely crypto-Jews who had arrived in Scotland in three phases: (1) with the arrival of William the Conqueror in 1066, (2) after the 1290 Expulsion of Jews from England, and (3) after the 1490 Expulsion of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula. Evidence is found that both the Ashkenazic and Sephardic branches of Judaism are present among these Lowland Scot and Northern Ireland residents. Keywords: Scotland, Northern Ireland, Sephardic Jews, Ashkenazic Jews, Genetic Genealogy --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 10-06-2021 Date of Acceptance: 25-06-2021 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- I. INTRODUCTION Scotland is stereotypically thought of as a Celtic, Protestant and fiercely independent country. The present research takes issue with the first of these stereotypes and seeks to modify the second one. Although Celtic influence in genetics and culture is certainly present in the Scottish Highlands, we propose that there is a strong undercurrent of Judaic ancestry in the Scottish Lowlands that has influenced the country from the 1100s to the present day. -

First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States Jason H. Greenberg The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1820 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] FROM ROCHEL TO ROSE AND MENDEL TO MAX: FIRST NAME AMERICANIZATION PATTERNS AMONG TWENTIETH-CENTURY JEWISH IMMIGRANTS TO THE UNITED STATES by by Jason Greenberg A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 Jason Greenberg All Rights Reserved ii From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States: A Case Study by Jason Greenberg This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics. _____________________ ____________________________________ Date Cecelia Cutler Chair of Examining Committee _____________________ ____________________________________ Date Gita Martohardjono Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States: A Case Study by Jason Greenberg Advisor: Cecelia Cutler There has been a dearth of investigation into the distribution of and the alterations among Jewish given names. -

2 La Convivencia: Did the Catholic Reconquest of Granada in 1492

La Convivencia: Did the Catholic reconquest of Granada in 1492 bring an end to peaceful religious coexistence in Southern Spain? The Muslim surrender of the vassal state of Granada on 2nd January 1492 completed the Catholic Reconquista1 of the Iberian Peninsula. Whilst at first a certain degree of tolerance was shown towards non-Catholics, forced conversions and expulsions overseen by the devout Isabella soon ensued. Many historians have portrayed the Muslim rule over Al- Andalus, the name given by the Muslims themselves to the region, as a multicultural paradise where the ‘People of the Book’ lived in harmony. Presumably then, the infamous Inquisition established under the Catholic Monarchs, attempting to consolidate Christian rule in newly unified Spain, would stand in great juxtaposition to this quasi-utopia. However, this society of religious coexistence which may have been the hallmark of Al-Andalus in its formative years was already beginning to deteriorate early in the eleventh century once power had shifted from Umayyad princes to nomadic Berber tribes. Thus, the notion of religious and cultural intolerance, albeit not carried out by the Berbers in such extreme measures, was firmly established in the Peninsula well before Muhammad XII, last Muslim ruler of Granada, handed over the keys of the city to Los Reyes Católicos. Throughout the eight-hundred years of Al-Andalus, the Peninsula did not remain under continuous dynastical rule. It began as a province of the Umayyad Caliphate in 711 AD, ruled by the Umayyad dynasty and based in Damascus, Syria. Once the Umayyads were overthrown by the Abbasid Dynasty, Al-Andalus became an independent Emirate under Abd al-Rahman, exiled Umayyad prince who established himself as Emir, or commander. -

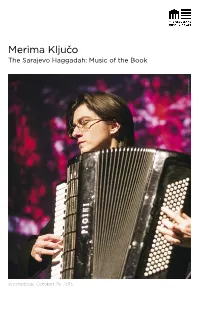

Merima Kljuc O

�������������� ���������������������������������������� ���������������������� ��������������������������� The Sarajevo Haggadah: ������������������������� Music of the Book ������������� Merima Ključo, composer and accordion ����������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� Seth Knopp, piano ������������������������������������������������������� Bart Woodstrup, artist ��������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������������������������������������� Geraldine Brooks, special guest ��������������������������������������������������� ������������������������������������������������������ Wednesday, October 28, 2015, 7:30 p.m. ����������������������������������������������������� Gartner Auditorium, the Cleveland Museum of Art ���������������� �������������������� ����������������������������������� Program ������������������������ Introduction by Geraldine Brooks �������������������������������������������� * * * * * �������������������������������� La Bendision de Madre (The Mother’s Prayer) found in a Sarajevo synagogue �������������������� ������������������������������ * * * * * The Creation ���������������������������������������������� �������������������������������� La Convivencia (The Coexistence) Al Mora Alhambra Decree Exodus In Silenzio Stampita Italkim The Inquisitor Sarajevo 1941 Derviš Korkut ������ ������������������������������������������������ ��������������������� Siege of Sarajevo La Bendision de Madre ��������������������������������������������� -

The 1492 Jewish Expulsion from Spain: How Identity Politics and Economics Converged

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2018 The 1492 ewJ ish Expulsion from Spain: How Identity Politics and Economics Converged Michelina Restaino Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Law and Economics Commons, Legislation Commons, Other Legal Studies Commons, and the Religion Law Commons Recommended Citation Restaino, Michelina, "The 1492 eJ wish Expulsion from Spain: How Identity Politics and Economics Converged" (2018). University Honors Program Theses. 325. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/325 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The 1492 Jewish Expulsion from Spain: How Identity Politics and Economics Converged An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in Department of History. By: Michelina Restaino Under the mentorship of Dr. Kathleen Comerford ABSTRACT In 1492, after Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand defeated the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula, they presented the Jewish community throughout their kingdoms with a choice: leaving or converting to Catholicism. The Spanish kingdoms had been anti-Jewish for centuries, forcing the creation of ghettos, the use of identifying clothing, etc. in an effort to isolate and “other” the Jews, who unsuccessfully sought peaceful co-existence. Those who did not accept expulsion, but converted, were the subject of further prejudice stemming from a belief that Jewish blood was tainted and that conversions were undertaken for financial gain.