'Crime and Utopia: Socialist and Anarchist Projections in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tommaso Campanella the Book and the Body of Nature Series: International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives Internationales D'histoire Des Idées

springer.com Germana Ernst Tommaso Campanella The Book and the Body of Nature Series: International Archives of the History of Ideas Archives internationales d'histoire des idées A comprehensive intellectual biography of an important and complex philosopher of the Renaissance A historical reconstruction of social and cultural relationships between the sixteenth and the seventeenth century A volume useful to clarify some philological and interpretative problems concerning modern editions and translations of Campanella’s texts A friend of Galileo and author of the renowned utopia The City of the Sun, Tommaso Campanella (Stilo, Calabria,1568- Paris, 1639) is one of the most significant and original thinkers of the early modern period. His philosophical project centred upon the idea of reconciling Renaissance philosophy with a radical reform of science and society. He produced a complex and articulate synthesis of all fields of knowledge – including magic and astrology. During his early formative years as a Dominican friar, he manifested a restless impatience 2010, XII, 281 p. towards Aristotelian philosophy and its followers. As a reaction, he enthusiastically embraced Bernardino Telesio’s view that knowledge could only be acquired through the observation of Printed book things themselves, investigated through the senses and based on a correct understanding of Hardcover the link between words and objects. Campanella’s new natural philosophy rested on the 139,99 € | £119.99 | $169.99 principle that the books written by men needed to be compared with God’s infinite book of [1]149,79 € (D) | 153,99 € (A) | CHF nature, allowing them to correct the mistakes scattered throughout the human ‘copies’ which 165,50 were always imperfect, partial and liable to revisions. -

Conversations with Stalin on Questions of Political Economy”

WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Lee H. Hamilton, Conversations with Stalin on Christian Ostermann, Director Director Questions of Political Economy BOARD OF TRUSTEES: ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Joseph A. Cari, Jr., by Chairman William Taubman Steven Alan Bennett, Ethan Pollock (Amherst College) Vice Chairman Chairman Working Paper No. 33 PUBLIC MEMBERS Michael Beschloss The Secretary of State (Historian, Author) Colin Powell; The Librarian of Congress James H. Billington James H. Billington; (Librarian of Congress) The Archivist of the United States John W. Carlin; Warren I. Cohen The Chairman of the (University of Maryland- National Endowment Baltimore) for the Humanities Bruce Cole; The Secretary of the John Lewis Gaddis Smithsonian Institution (Yale University) Lawrence M. Small; The Secretary of Education James Hershberg Roderick R. Paige; (The George Washington The Secretary of Health University) & Human Services Tommy G. Thompson; Washington, D.C. Samuel F. Wells, Jr. PRIVATE MEMBERS (Woodrow Wilson Center) Carol Cartwright, July 2001 John H. Foster, Jean L. Hennessey, Sharon Wolchik Daniel L. Lamaute, (The George Washington Doris O. Mausui, University) Thomas R. Reedy, Nancy M. Zirkin COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. -

Reading William Morris, Peter Kropotkin, Ursula K. Le Guin, and PM in the Light of Digital Socialism

tripleC 18(1): 146-186, 2020 http://www.triple-c.at The Utopian Internet, Computing, Communication, and Concrete Utopias: Reading William Morris, Peter Kropotkin, Ursula K. Le Guin, and P.M. in the Light of Digital Socialism Christian Fuchs University of Westminster, London, [email protected], http://fuchs.uti.at Abstract: This paper asks: What can we learn from literary communist utopias for the creation and organisation of communicative and digital socialist society and a utopian Internet? To pro- vide an answer to this question, the article discusses aspects of technology and communica- tion in utopian-communist writings and reads these literary works in the light of questions con- cerning digital technologies and 21st-century communication. The selected authors have writ- ten some of the most influential literary communist utopias. The utopias presented by these authors are the focus of the reading presented in this paper: William Morris’s (1890/1993) News from Nowhere, Peter Kropotkin’s (1892/1995) The Conquest of Bread, Ursula K. Le Guin’s (1974/2002) The Dispossessed, and P.M.’s (1983/2011; 2009; 2012) bolo’bolo and Kartoffeln und Computer (Potatoes and Computers). These works are the focus of the reading presented in this paper and are read in respect to three themes: general communism, technol- ogy and production, communication and culture. The paper recommends features of concrete utopian-communist stories that can inspire contemporary political imagination and socialist consciousness. The themes explored include the role of post-scarcity, decentralised comput- erised planning, wealth and luxury for all, beauty, creativity, education, democracy, the public sphere, everyday life, transportation, dirt, robots, automation, and communist means of com- munication (such as the “ansible”) in digital communism. -

Marx's Confrontation with Utopia Darren Webb Department of Politics

In Search of the Spirit of Revolution: Marx's Confrontation with Utopia Darren Webb Department of Politics Thesis presented to the University of Sheffield for the degree of PhD, June 1998 Summary This thesis offers a sympathetic interpretation of Marx' s confrontation with Utopia. It begins by suggesting that Marx condemned utopianism as a political process because it undermined the principles of popular self-emancipation and self-determination, principles deemed by Marx to be fundamental to the constitution of any truly working class movement. As a means of invoking the spirit of revolution, it was therefore silly, stale and reactionary. With regards to Marx's own 'utopia', the thesis argues that the categories which define it were nothing more than theoretical by-products of the models employed by Marx in order to supersede the need for utopianism. As such, Marx was an 'Accidental Utopian'. Two conclusions follow from this. The first is that Marx's entire project was driven by the anti-utopian imperative to invoke the spirit of revolution in a manner consistent with the principles of popular self-emancipation and self-determination. The second is that, in spite of his varied attempts to do so, Marx was unable to capture the spirit of revolution without descending into utopianism himself Such conclusions do not, however, justify the claim that utopianism has a necessary role to play in radical politics. For Marx's original critique of utopianism was accurate and his failure to develop a convincing alternative takes nothing away from this. The accuracy of Marx's original critique is discussed in relation to the arguments put forward by contemporary pro-utopians as well as those developed by William Morris, Ernst Bloch and Herbert Marcuse. -

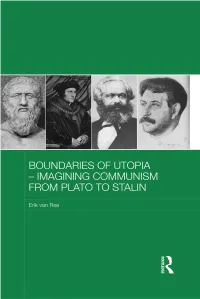

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin

Boundaries of Utopia – Imagining Communism from Plato to Stalin The idea that socialism could be established in a single country was adopted as an official doctrine by the Soviet Union in 1925, Stalin and Bukharin being the main formulators of the policy. Before this there had been much debate as to whether the only way to secure socialism would be as a result of socialist revolution on a much broader scale, across all Europe or wider still. This book traces the development of ideas about communist utopia from Plato onwards, paying particular attention to debates about universalist ideology versus the possibility for ‘socialism in one country’. The book argues that although the prevailing view is that ‘socialism in one country’ was a sharp break from a long tradition that tended to view socialism as only possible if universal, in fact the territorially confined socialist project had long roots, including in the writings of Marx and Engels. Erik van Ree is an Assistant Professor at the Institute of European Studies at the University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Routledge Contemporary Russia and Eastern Europe Series 1 Liberal Nationalism in 7 The Telengits of Central Europe Southern Siberia Stefan Auer Landscape, religion and knowledge in motion 2 Civil-Military Relations in Agnieszka Halemba Russia and Eastern Europe David J. Betz 8 The Development of Capitalism in Russia 3 The Extreme Nationalist Simon Clarke Threat in Russia The growing influence of 9 Russian Television Today Western Rightist ideas Primetime drama and comedy Thomas Parland -

Utopia & Terror in the 20Th Century.Pdf

Utopia and Terror in the 20th Century Part I Professor Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius THE TEACHING COMPANY ® Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History, University of Tennessee Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius was born in Chicago, Illinois. He grew up on Chicago’s Southside in a Lithuanian- American neighborhood and spent some years attending school in Aarhus, Denmark, and Bonn, Germany. He received his B.A. from the University of Chicago. In 1989, he spent the summer in Moscow and Leningrad (today St. Petersburg) in intensive language study in Russian. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in European history in 1994, specializing in modern German history. After receiving his doctorate, Professor Liulevicius spent a year as a postdoctoral research fellow at the Hoover Institution on War, Peace, and Revolution at Stanford University in Palo Alto, California. Since 1995, he has been a history professor at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. He teaches courses on modern German history, Western civilization, Nazi Germany, World War I, war and culture, 20th-century Europe, nationalism, and utopian thought. In 2003, he received the University of Tennessee’s Excellence in Teaching award. Professor Liulevicius’s research focuses on German relations with Eastern Europe in the modern period. His other interests include the utopian tradition and its impact on modern politics, images of the United States abroad, and the history of Lithuania and the Baltic region. He has published numerous articles and his first book, War Land on the Eastern Front: Culture, National Identity and German Occupation in the First World War (2000), published by Cambridge University Press, also appeared in German translation in 2002. -

Sos Political Science & Public Administration M.A.Political Science

Sos Political science & Public administration M.A.Political Science II Sem Political Philosophy:Mordan Political Thought, Theory & contemporary Ideologies(201) UNIT-IV Topic Name-Utopian Socialism What is utopian society? • A utopia is an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its citizens.The opposite of a utopia is a dystopia. • Utopia focuses on equality in economics, government and justice, though by no means exclusively, with the method and structure of proposed implementation varying based on ideology.According to Lyman Tower SargentSargent argues that utopia's nature is inherently contradictory, because societies are not homogenous and have desires which conflict and therefore cannot simultaneously be satisfied. • The term utopia was created from Greek by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book Utopia, describing a fictional island society in the south Atlantic Ocean off the coast of South America Who started utopian socialism? • Charles Fourier was a French socialist who lived from 1772 until 1837 and is credited with being an early Utopian Socialist similar to Robert Owen. He wrote several works related to his socialist ideas which centered on his main idea for society: small communities based on cooperation Definition of utopian socialism • socialism based on a belief that social ownership of the means of production can be achieved by voluntary and peaceful surrender of their holdings by propertied groups What is the goal of utopian societies? • The aim of a utopian society is to promote the highest quality of living possible. The word 'utopia' was coined by the English philosopher, Sir Thomas More, in his 1516 book, Utopia, which is about a fictional island community. -

The Walsall Anarchists: Trapped by the Police : Innocent Men in Penal Servitude : the Truth About the Walsall Plot

The Walsall anarchists: trapped by the police : innocent men in penal servitude : the truth about the Walsall plot. Author(s): Nicoll, David J.?. Source: LSE Selected Pamphlets, (1892) Published by: LSE Library Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/60215295 . Accessed: 30/09/2013 04:22 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Digitization of this work funded by the JISC Digitisation Programme. LSE Library and are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to LSE Selected Pamphlets. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 146.87.136.26 on Mon, 30 Sep 2013 04:22:06 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions m THE \-> Walsall /\r\ara\iSra. TRAPPED BY THE POLICE. Innocent Men in Penal Servitude. The Truth about the Walsall Plot. N.B.—These Revelations Were suppressed by the police " When they raided the Offices of the GommorvWeal," on April 18th, 1892. PRICE ONE PENNY. •*jm Printed and Published by DAVID NICOLL, at 194, Clarence Road, Kentish Town, London, N.W. This content downloaded from 146.87.136.26 on Mon, 30 Sep 2013 04:22:06 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions By Peter Kropotkine. -

Philosophy of Mind

Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY: PHILOSOPHY OF MIND ERAN ASOULIN, PAUL RICHARD BLUM, TONY CHENG, DANIEL HAAS, JASON NEWMAN, HENRY SHEVLIN, ELLY VINTIADIS, HEATHER SALAZAR (EDITOR), AND CHRISTINA HENDRICKS (SERIES EDITOR) Rebus Community Introduction to Philosophy: Philosophy of Mind by Eran Asoulin, Paul Richard Blum, Tony Cheng, Daniel Haas, Jason Newman, Henry Shevlin, Elly Vintiadis, Heather Salazar (Editor), and Christina Hendricks (Series Editor) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. CONTENTS What is an open textbook? vii Christina Hendricks How to access and use the books ix Christina Hendricks Introduction to the Series xi Christina Hendricks Praise for the Book xiv Adriano Palma Acknowledgements xv Heather Salazar and Christina Hendricks Introduction to the Book 1 Heather Salazar 1. Substance Dualism in Descartes 3 Paul Richard Blum 2. Materialism and Behaviorism 10 Heather Salazar 3. Functionalism 19 Jason Newman 4. Property Dualism 26 Elly Vintiadis 5. Qualia and Raw Feels 34 Henry Shevlin 6. Consciousness 41 Tony Cheng 7. Concepts and Content 49 Eran Asoulin 8. Freedom of the Will 58 Daniel Haas About the Contributors 69 Feedback and Suggestions 72 Adoption Form 73 Licensing and Attribution Information 74 Review Statement 76 Accessibility Assessment 77 Version History 79 WHAT IS AN OPEN TEXTBOOK? CHRISTINA HENDRICKS An open textbook is like a commercial textbook, except: (1) it is publicly available online free of charge (and at low-cost in print), and (2) it has an open license that allows others to reuse it, download and revise it, and redistribute it. -

Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989–2000 Rls 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Texte 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung

Wolfram Adolphi (Hrsg.) Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989–2000 rls 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Texte 12 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung WOLFRAM ADOLPHI (HRSG.) Michael Schumann Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989-2000 Mit einem Geleitwort von Lothar Bisky Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin Herausgegeben mit Unterstützung der PDS-Fraktion im Landtag Brandenburg. Ein besonderer Dank gilt Herrn Marco Schumann, Potsdam, für seine Hilfe und Mitarbeit. Wolfram Adolphi (Hrsg.): Michael Schumann. Hoffnung PDS Reden, Aufsätze, Entwürfe 1989-2000. Mit einem Geleitwort von Lothar Bisky (Reihe: Texte/Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung; Bd. 12) Berlin: Dietz, 2004 ISBN 3-320-02948-7 © Karl Dietz Verlag Berlin GmbH 2004 Satz: Jörn Schütrumpf Umschlag, Druck und Verarbeitung: MediaService GmbH BärenDruck und Werbung Printed in Germany Inhalt LOTHAR BISKY Zum Geleit 9 WOLFRAM ADOLPHI Vorwort 11 Abschnitt 1 Zum Herkommen und zur Entwicklung der PDS Wir brechen unwiderruflich mit dem Stalinismus als System! Referat auf dem Außerordentlichen Parteitag der SED in Berlin am 16. Dezember 1989 33 Von der SED zur PDS – geht die Rechnung auf? Interview für die Tageszeitung »Neues Deutschland« vom 26. Januar 1990 57 Programmatik und politisches System Artikel für die vom PDS-Parteivorstand herausgegebene Zeitschrift »Disput«, Heft 14/1992 (2. Juliheft) 69 Souverän mit unserer politischen Biographie umgehen Referat auf dem 3. Parteitag der PDS in Berlin (19.-21. Januar 1993) 74 Der Logik des Kräfteverhältnisses stellen! Rede auf dem 12. Parteitag der DKP, Gladbeck, am 13. November 1993 90 5 Vor fünf Jahren: »Wir brechen unwiderruflich mit dem Stalinismus als System!« Reminiszenzen und aktuelle Überlegungen 94 Antikommunismus? Schlußwort auf dem Historisch-rechtspolitischen Kolloquium »KPD-Verbot oder mit Kommunisten leben? Das KPD-Verbotsurteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichts vom 17. -

Socialism and the Blockchain

future internet Article Socialism and the Blockchain Steve Huckle * and Martin White Creative Technology Group, Department of Informatics, University of Sussex, Chichester 1, 128, Falmer, Brighton BN1 9QT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-0-1273-606755 Academic Editor: Carmen de Pablos Heredero Received: 5 August 2016; Accepted: 10 October 2016; Published: 18 October 2016 Abstract: Bitcoin (BTC) is often cited as Libertarian. However, the technology underpinning Bitcoin, blockchain, has properties that make it ideally suited to Socialist paradigms. Current literature supports the Libertarian viewpoint by focusing on the ability of Bitcoin to bypass central authority and provide anonymity; rarely is there an examination of blockchain technology’s capacity for decentralised transparency and auditability in support of a Socialist model. This paper conducts a review of the blockchain, Libertarianism, and Socialist philosophies. It then explores Socialist models of public ownership and looks at the unique cooperative properties of blockchain that make the technology ideal for supporting Socialist societies. In summary, this paper argues that blockchain technologies are not just a Libertarian tool, they also enhance Socialist forms of governance. Keywords: Bitcoin; blockchain; cryptocurrency; fiat money; libertarianism; socialism; Marxism; anarchism 1. Introduction Bitcoin (BTC) is referred to as cryptocurrency because it is a form of electronic cash that relies on cryptography. Since its inception in early 2009 [1], it has achieved a degree of prominence, not least in terms of market value; at the time of writing, its total market capitalisation was over US $6 billion [2]. Furthermore, governmental institutions are beginning to examine the blockchain technology underpinning BTC [3] because some of its properties, which we discuss below, may have implications that extend beyond economics and into social, political and humanitarian domains [4]. -

Mnfittt of Cbutation

GANDHI'S SOCIALISM AND ITS IMPACT ON EDUCATION DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Mnfittt of Cbutation BY Naseemul Haque Ansari Exam. Roll No. 3117 82 M. Ed.-9 Enrolment NO.-P-9708 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Dr. (Miss) Shakuntala Saxena Reader DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 1982-83 :P^^AZA *iO v >.,, .. •i>S5 9g. •^ JNtVKS''^ 25 MAYI985 r'^t^r'^'4"» 9^ fw DS598 CHEC;;„D-2033 CERTIFICATE Certified that Mr. Naseemul Haque Ansari has completed his dissertation entitled "Gandhi's Socialism and Its Impact on Education," under my supervision and, submitted for partial fulfilment of the degree of Master of Education in session 1982-83, ( Dr. (Miss) Sh^cuntala Saxena ) Supervisor ACKKOWLEDGEhENTS Acknowledging the help made available to me can never repay their labour and love extended to me. Keeping with the tradition I, therefore, extend my profound gratitude to Dr.(Miss) Shakuntala Saxena, Reader, Department of Education, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh without v/hose unremitting able guidance, sympathetic attitude and deep interest in the study, it would not have been possible for me to complete this dissertation. My sincere thanks are for Mr. Syed.Md. Noman for his ever available great contribution and making him available all the time for his selfless help. I am also greatful to Mr. Md. Parvez, Mr. Salman Israiely, Mr. Haseenuddin and Mr. Ejaz Ahmed Khan who provided their full support and cooperation in making the reference books available and thus enabling me to proceed with my work v/ithout any impediment. Besides help also came indirectly from several friends and office bearers to whoi^e I will always be thankful.