Human Trafficking and Trauma in the Digital Era: the Ongoing Tragedy of the Trade in Refugees from Eritrea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

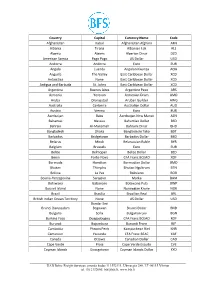

Country, Capital, Currency

List of all Countries, Capitals & Currencies of the World Country Capital Currency Afghanistan Kabul Afghan afghani Albania Tirana Albanian lek Algeria Agiers Algerian dinar Andorra Andorra la Vella Euro Angola Luanda Kwanza Antigua and Barbuda St. John’s East Caribbean dollar Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine peso Armenia Yerevan Armenian dram Australia Canberra Australian dollar Austria Vienna Euro Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijani manat Bahamas Nassau Bahamian dollar Bahrain Manama Bahraini dinar Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi taka Barbados Bridgetown Barbadian dollar Belarus Minsk Belarusian ruble Belgium Brussels Euro Belize Belmopan Belize dollar Benin Porto-Novo (official) West African CFA franc Bhutan Thimpu Bhutanese ngultrum Bolivia Sucre Bolivian boliviano Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevo Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark Botswana Gaborone Pula Brazil Brasília Brazilian real Brunei Bandar Seri Begawan Brunei dollar Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian lev Burkina Faso Ouagadougou West African CFA franc Burundi Bujumbura Burundian franc Cambodia Phnom Penh Cambodian riel Cameroon Yaoundé Central African CFA franc Canada Ottawa Canadian dollar Cape Verde Praia Cape Verdean escudo Central African Republic Bangui Central African CFA franc Chad N’Djamena Central African CFA franc Chile Santiago Chilean peso China Beijing Chinese Yuan Renminbi Colombia Bogotá Colombian peso Comoros Moroni Comorian franc Costa Rica San José Costa Rican colon Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) Yamoussoukro (official),Abidjan West African CFA franc (seat of government) Croatia -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

Country Scheme Alpha 3 Alpha 2 Currency Albania MC / VI ALB AL

Country Scheme Alpha 3 Alpha 2 Currency Albania MC / VI ALB AL Lek Algeria MC / VI DZA DZ Algerian dinar Argentina MC / VI ARG AR Argentine peso Australia MC / VI AUS AU Australian dollar -Christmas Is. -Cocos (Keeling) Is. -Heard and McDonald Is. -Kiribati -Nauru -Norfolk Is. -Tuvalu Christmas Island MC CXR CX Australian dollar Cocos (Keeling) Islands MC CCK CC Australian dollar Heard and McDonald Islands MC HMD HM Australian dollar Kiribati MC KIR KI Australian dollar Nauru MC NRU NR Australian dollar Norfolk Island MC NFK NF Australian dollar Tuvalu MC TUV TV Australian dollar Bahamas MC / VI BHS BS Bahamian dollar Bahrain MC / VI BHR BH Bahraini dinar Bangladesh MC / VI BGD BD Taka Armenia VI ARM AM Armenian Dram Barbados MC / VI BRB BB Barbados dollar Bermuda MC / VI BMU BM Bermudian dollar Bolivia, MC / VI BOL BO Boliviano Plurinational State of Botswana MC / VI BWA BW Pula Belize MC / VI BLZ BZ Belize dollar Solomon Islands MC / VI SLB SB Solomon Islands dollar Brunei Darussalam MC / VI BRN BN Brunei dollar Myanmar MC / VI MMR MM Myanmar kyat (effective 1 November 2012) Burundi MC / VI BDI BI Burundi franc Cambodia MC / VI KHM KH Riel Canada MC / VI CAN CA Canadian dollar Cape Verde MC / VI CPV CV Cape Verde escudo Cayman Islands MC / VI CYM KY Cayman Islands dollar Sri Lanka MC / VI LKA LK Sri Lanka rupee Chile MC / VI CHL CL Chilean peso China VI CHN CN Colombia MC / VI COL CO Colombian peso Comoros MC / VI COM KM Comoro franc Costa Rica MC / VI CRI CR Costa Rican colony Croatia MC / VI HRV HR Kuna Cuba VI Czech Republic MC / VI CZE CZ Koruna Denmark MC / VI DNK DK Danish krone Faeroe Is. -

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

PUB CATE 70 NOTE 136P.;(178 References) ERRS PRICE MF

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 07-784 LI 004 194 TITLE International Library Manpower; Education and Placement in North America (ALA Preconference Institute. Detroit, Michigan; June 26-27, 1970). Education for Librarianship: Country Fact Sheets. INSTITUTION American Library Association, Chicago, Ill. Office for Library Education.; Pratt Inst., Brooklyn, N.Y. Graduate School of Library and Information Science.; Wayne State Univ., Detroit, Mich. Dept. of Library Science. PUB CATE 70 NOTE 136p.;(178 References) ERRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Conference Reports; *Foreign Countries; *Librarians; Library Associations; *Library Education; Library Schools; Library Standards; Manpower Development IDENTIFIERS *Librarianship AESTRACT Fact sheets on the general education system and education for librarianship are presented for 49 countries. The following countries are represented: Algeria, Australia, Austria, Burma, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Denmark, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Germany Ghana, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Jordan, Korea, Kuwait, Latin America, Lebanon, Libya, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria, Taiwan (Formosa), Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Republic, United Kingdom, Uruguay, Venezuela, Viet Nam, West Africa, Yemen.(A related document is LI 004193.) (03) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY U S DEPARTMENT OF HTAllti FOUCATION A WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS Li EiN trkit, DIXED EXACTLY AS r Trt f Rom THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION 0516 INATINO IT POINTS OF VIEW 05 (+PIN IONS STATER DO NW NEt:rr,',1,,, REPRESENT OFT-KART (II I It.E of ,00 CATION POSITION OtHPOLICY INTERNATIONAL LIBRARY MANPOWER EDUCATION AND PLACEMENT IN NORTH AMERICA. ALA Preconference Institute. Detroit, Michigan June 2.6- 27, 1970 EDUCATION FORAABRARIANSHIP: COUNTRY FACT SHEETS. -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

Status of Postgraduate Training in the Livestock Sector in East and Central Africa and Priorities for ILRI’S Support

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CGSpace Status of postgraduate training in the livestock sector in East and Central Africa and priorities for ILRI’s support ILRI INTERNATIONAL LIVESTOCK RESEARCH INSTITUTE Status of postgraduate training in the livestock sector in East and Central Africa and priorities for ILRI’s support International Livestock Research Institute Capacity Strengthening Unit (CaSt) Lusato R Kurwijila May 2009 i © 2009 ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute). All rights reserved. Parts of this publication may be reproduced for non-commercial use provided that such reproduction shall be subject to acknowledgement of ILRI as holder of copyright. Editing, design and layout—ILRI Publication Unit, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Correct citation: Kurwijila LR. 2009. Status of postgraduate training in the livestock sector in East and Central Africa and priorities for ILRI’s support. ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute), Nairobi, Kenya. 42 pp. ii Table of Contents List of Tables iv Acronyms and abbreviations v Acknowledgements vii Preface viii Executive summary ix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background and rationale 1 1.2 Objective/terms of reference 2 1.3 Approach and methodology 3 1.4 Outline of the report 3 2 Current profile of livestock training in the region 4 2.1 Importance of the livestock sector in the region 4 2.2 Emerging challenges of livestock production in the ASARECA region 5 2.3 Different categories of livestock training institutes 7 2.4 Current status -

List of Currencies That Are Not on KB´S Exchange Rate

LIST OF CURRENCIES THAT ARE NOT ON KB'S EXCHANGE RATE , BUT INTERNATIONAL PAYMENTS IN THESE CURRENCIES CAN BE MADE UNDER SPECIFIC CONDITIONS ISO code Currency Country in which the currency is used AED United Arab Emirates Dirham United Arab Emirates ALL Albanian Lek Albania AMD Armenian Dram Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh ANG Netherlands Antillean Guilder Curacao, Sint Maarten AOA Angolan Kwanza Angola ARS Argentine Peso Argentine BAM Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark Bosnia and Herzegovina BBD Barbados Dollar Barbados BDT Bangladeshi Taka Bangladesh BHD Bahraini Dinar Bahrain BIF Burundian Franc Burundi BOB Boliviano Bolivia BRL Brazilian Real Brazil BSD Bahamian Dollar Bahamas BWP Botswana Pula Botswana BYR Belarusian Ruble Belarus BZD Belize Dollar Belize CDF Congolese Franc Democratic Republic of the Congo CLP Chilean Peso Chile COP Colombian Peso Columbia CRC Costa Rican Colon Costa Rica CVE Cape Verde Escudo Cape Verde DJF Djiboutian Franc Djibouti DOP Dominican Peso Dominican Republic DZD Algerian Dinar Algeria EGP Egyptian Pound Egypt ERN Eritrean Nakfa Eritrea ETB Ethiopian Birr Ethiopia FJD Fiji Dollar Fiji GEL Georgian Lari Georgia GHS Ghanaian Cedi Ghana GIP Gibraltar Pound Gibraltar GMD Gambian Dalasi Gambia GNF Guinean Franc Guinea GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal Guatemala GYD Guyanese Dollar Guyana HKD Hong Kong Dollar Hong Kong HNL Honduran Lempira Honduras HTG Haitian Gourde Haiti IDR Indonesian Rupiah Indonesia ILS Israeli New Shekel Israel INR Indian Rupee India, Bhutan IQD Iraqi Dinar Iraq ISK Icelandic Króna Iceland JMD Jamaican -

Impacts of Sida/Sweden Support to AAU/Ethiopia (2008-2017)

A Long Journey to Success: Impacts of Sida/Sweden Support to AAU/Ethiopia (2008-2017) Documented by the Grants’ Coordination Office, AAU Brook Lemma, Mastewal Moges and Echu Teshome July 2017 Addis Ababa ii AAU-SIDA Achievements: 2008-2017 Publisher’s page: This book is property of Addis Ababa University. The data that are contained in this book regarding the graduate program of AAU, particularly that of the PhD programs, came from actual records of the Grants’ Coordination Office of AAU. Any reference made from this book should be formally acknowledged. This book can be referred to as follows. Brook Lemma, Mastewal Moges and Echu Teshome (2017): A Long Journey to Success: Impacts of Sida/Sweden Support to AAU/Ethiopia (2008-2017). Compiled by the Grants’ Coordination Office of AAU and Published at AAU Printing Press, Addis Ababa; 92 pp. Cover page images Upper: From left to right, His Excellency Hailemariam Desalegn providing the award certificate, Professor Admasu Tsegaye, former President of AAU and His Excellency Ambassador Dr. Jan Sadek, Ambassador of Sweden receiving the award on behalf of Sida and himself. Lower: From left to right, Professor Admasu Tsegaye, former President of AAU, Dr. Jan Sadek receiving the award on behalf of Sida and himself, His Excellency Ato Kassa Tekleberhan, Chairman of AAU Board and Dr. Jeilu Oumer, Academic Vice President of AAU Background iii CONTENTS Table of Contents ........................................................................................... iii Acronym .......................................................................................................... -

HED/USAID Higher Education Partnerships in Africa 1997–2007

® HED/USAID Higher Education Partnerships in Africa 1997–2007 Prepared by Christine Morfit, M.I.P.P., Executive Director, Higher Education for Development (through spring 2008) Jane Gore, PhD, Senior Evaluation Specialist, Higher Education for Development P. Bai Akridge, PhD, President, WorldWise Services, Inc. Reissued in spring 2009 U.S. Higher Education Partnerships in Africa 1997 - 2007 Prepared by: Christine Morfit, M.I.P.P., Executive Director (through Spring 2008), Higher Education for Development Jane Gore, PhD, Senior Evaluation Specialist, Higher Education for Development P. Bai Akridge, PhD, President, WorldWise Services, Inc. Published in Spring 2009 CONTENTS Page Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 1 Background: U.S.-International Higher Education Partnerships ....................................... 4 HED African Partnerships: Assessment of Impacts .......................................................... 7 • International Science and Technology Institute (ISTI) ………….………………..8 • Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI)…...…………………………………...11 • 2007 HED Synergy Conference ………………………………………………….13 Partnership Contributions to Capacity Building as Cost-Effective Foreign Assistance.....17 Lessons Learned ................................................................................................................18 Conclusion .........................................................................................................................21 -

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary material BMJ Global Health Supplementary Table 1 List of African Universities and description of training or research offerings in biological science, medicine and public health disciplines Search completed Dec 3rd, 2016 Sources: 4icu.org/africa and university websites University Name Country/State City Website School of School of School of Biological Biological Biological Biological Medicine Public Health Science, Science, Science, Science Undergraduate Masters Doctoral Level Level Universidade Católica Angola Luanda http://www.ucan.edu/ No No Yes No No No Agostinhode Angola Neto Angola Luanda http://www.agostinhone Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes UniversidadeUniversity Angola Luanda http://www.unia.ao/to.co.ao/ No No No No No No UniversidadeIndependente Técnica de de Angola Luanda http://www.utanga.co.ao No No No No No No UniversidadeAngola Metodista Angola Luanda http://www.uma.co.ao// Yes No Yes Yes No No Universidadede Angola Mandume Angola Huila https://www.umn.ed.ao Yes Yes No Yes No No UniversidadeYa Ndemufayo Jean Angola Viana http://www.unipiaget- No Yes No No No No UniversidadePiaget de Angola Óscar Angola Luanda http://www.uor.ed.ao/angola.org/ No No No No No No UniversidadeRibas Privada de Angola Luanda http://www.upra.ao/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeAngola Kimpa Angola Uíge http://www.unikivi.com/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeVita Katyavala Angola Benguela http://www.ukb.ed.ao/ No Yes No No No No UniversidadeBwila Gregório Angola Luanda http://www.ugs.ed.ao/ No No No No No No UniversidadeSemedo José Angola Huambo http://www.ujes-ao.org/ No Yes No No No No UniversitéEduardo dos d'Abomey- Santos Benin Atlantique http://www.uac.bj/ Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Calavi Université d'Agriculture Benin Plateau http://www.uakbenin.or No No No No No No de Kétou g/ Université Catholique Benin Littoral http://www.ucao-uut.tg/ No No No No No No de l'Afrique de l'Ouest Université de Parakou Benin Borgou site cannot be reached No Yes Yes No No No Moïsi J, et al. -

They Are Making Us Into Slaves, Not Educating Us” How Indefinite Conscription Restricts Young People’S Rights, Access to Education in Eritrea

HUMAN “They Are Making Us into Slaves, RIGHTS Not Educating Us” WATCH How Indefinite Conscription Restricts Young People’s Rights, Access to Education in Eritrea “They Are Making Us into Slaves, Not Educating Us” How Indefinite Conscription Restricts Young People’s Rights, Access to Education in Eritrea Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-37526 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org AUGUST 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-37526 “They Are Making Us into Slaves, Not Educating Us” How Indefinite Conscription Restricts Young People’s Rights, Access to Education in Eritrea Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 “Sawa” as a Recruitment Channel .............................................................................................