Proustian Metaphor and the Automobile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: DOI: 10.7766/Orbit.V1.1.30

Orbit: Writing Around Pynchon https://www.pynchon.net ISSN: 2044-4095 Author(s): Erik Ketzan Affiliation(s): Institut für Deutsche Sprache, Mannheim, Germany Title: Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Date: 2012 Volume: 1 Issue: 1 URL: https://www.pynchon.net/owap/article/view/30 DOI: 10.7766/orbit.v1.1.30 Abstract: This paper argues that Pynchon may allude to Marcel Proust through the character Marcel in Part 4 of Gravity's Rainbow and, if so, what that could mean. I trace the textual clues that relate to Proust and analyze what Pynchon may be saying about a fellow great experimental writer. Pynchon Nods: Proust in Gravity's Rainbow Erik Ketzan Editorial note: a previous draft of this paper appeared on The Modern Word in 2010. Remember the "Floundering Four" part in Gravity's Rainbow? It's a short story of sorts that takes place in a city of the future called Raketen-Stadt (German for "Rocket City") and features a cast of comic book-style super heroes called the Floundering Four. One of them is named Marcel, and I submit that he is meant as some kind of representation of the great Marcel Proust. Only eight pages long, the Floundering Four section is a parody/riff on a sci-fi comic book story, loosely patterned on The Fantastic Four by Marvel Comics. It appears near the end of Gravity's Rainbow among a set of thirteen chapterettes, each one a fragmentary "text". As Pynchon scholar Steven Weisenburger explains, "A variety of discourses, modes and forms are parodied in the… subsections.. -

Jonathan Greenberg

Losing Track of Time Jonathan Greenberg Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation tells a story of doing nothing; it is an antinovel whose heroine attempts to sleep for a year in order to lose track of time. This desire to lose track of time constitutes a refusal of plot, a satiric and passive- aggressive rejection of the kinds of narrative sequences that novels typically employ but that, Moshfegh implies, offer nothing but accommodation to an unhealthy late capitalist society. Yet the effort to stifle plot is revealed, paradoxically, as an ambi- tion to be achieved through plot, and so in resisting what novels do, My Year of Rest and Relaxation ends up showing us what novels do. Being an antinovel turns out to be just another way of being a novel; in seeking to lose track of time, the novel at- tunes us to our being in time. Whenever I woke up, night or day, I’d shuffle through the bright marble foyer of my building and go up the block and around the corner where there was a bodega that never closed.1 For a long time I used to go to bed early.2 he first of these sentences begins Ottessa Moshfegh’s 2018 novelMy Year of Rest and Relaxation; the second, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. More ac- T curately, the second sentence begins C. K. Scott Moncrieff’s translation of Proust, whose French reads, “Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure.” D. J. Enright emends the translation to “I would go to bed”; Lydia Davis and Google Translate opt for “I went to bed.” What the translators famously wrestle with is how to render Proust’s ungrammatical combination of the completed action of the passé composé (“went to bed”) with a modifier (“long time”) that implies a re- peated, habitual, or everyday action. -

Anthony Tropolle Life of Cicero

ANTHONY TROPOLLE LIFE OF CICERO VOLUME I 2008 – All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted HE LIFE OF CICERO BY ANTHONY TROLLOPE _IN TWO VOLUMES_ VOL. I. CONTENTS OF VOLUME I. CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION. CHAPTER II. HIS EDUCATION. CHAPTER III. THE CONDITION OF ROME. CHAPTER IV. HIS EARLY PLEADINGS.--SEXTUS ROSCIUS AMERINUS.--HIS INCOME. CHAPTER V. CICERO AS QUAESTOR. CHAPTER VI. VERSES. CHAPTER VII. CICERO AS AEDILE AND PRAETOR. CHAPTER VIII. CICERO AS CONSUL. CHAPTER IX. CATILINE. CHAPTER X. CICERO AFTER HIS CONSULSHIP. CHAPTER XI. THE TRIUMVIRATE. CHAPTER XII. HIS EXILE. * * * * * APPENDICES. APPENDIX A. APPENDIX B. APPENDIX C. APPENDIX D. APPENDIX E. THE LIFE OF CICERO. CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION. I am conscious of a certain audacity in thus attempting to give a further life of Cicero which I feel I may probably fail in justifying by any new information; and on this account the enterprise, though it has been long considered, has been postponed, so that it may be left for those who come after me to burn or publish, as they may think proper; or, should it appear during my life, I may have become callous, through age, to criticism. The project of my work was anterior to the life by Mr. Forsyth, and was first suggested to me as I was reviewing the earlier volumes of Dean Merivale's History of the Romans under the Empire. In an article on the Dean's work, prepared for one of the magazines of the day, I inserted an apology for the character of Cicero, which was found to be too long as an episode, and was discarded by me, not without regret. -

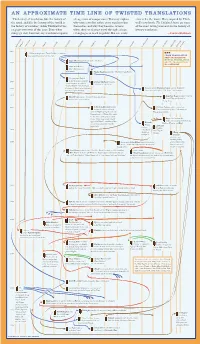

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE of TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The History of Translation, Like the History of a Long Series of Compromises

AN APPROXIMATE TIME LINE OF TWISTED TRANSLATIONS “The history of translation, like the history of a long series of compromises. This may explain error is for the worse. Here, inspired by Thirl- the novel, and like the history of the world, is why some novelists refuse every translator but well’s new book, The Delighted States, are some the history of mistakes,” Adam Thirlwell writes themselves, and why they become anxious of the most vexing moments in the history of on page seventeen of this issue. Even when when their work must travel through a chain literary translation. things go well, however, any translation requires of languages to reach its public. But not every —Jascha Hoffman E N S E A N H I H H N N U N H H A C A S H S I C S A A H G A S I S N L I H H I I C I I I I B B L M S U D A A T C C N N S I T S N D U B A T G E R L S E R T L E N R R A D L R A E Z U N I R E E O O U P W I O A A C C C D E F F G P P P R S S Y Y 1490 KEY: A Valencian knight writes Tirant Lo Blanc in Catalan. CHAIN TRANSLATION It is finished by a friend after his death. SELF TRANSLATION Edgar Allan Poe publishes his poem “The Raven.” MUTUAL TRANSLATION 1850 GROUP TRANSLATION NO CATEGORY Lewis Carroll writes Alice’s Adventures in W onderland. -

Wine.Kittlehouse Wine List 8.10

! The Story of the Wine Cellar at Crabtree’s Kittle House Restaurant and Inn The year was 1988 and John Crabtree’s idea was to create one of the greatest restaurant wine lists in the world. Grounded in the belief that great winemakers make great wine, we set out to learn who the world’s greatest winemakers were - the talented people making the most compelling and delicious wines of their type, creating the greatest expressions of a special place, the grapes that grow there and that winemaker’s vision of how that wine should taste. When we started our wine journey, the Kittle House wine list had about 150 selections and the wine cellar held a few thousand bottles and took up a small fraction of the space compared to what it is today. Both the list and the cellar grew very fast. We invited winemakers to the Kittle House for winemaker dinners and travelled to meet them on their estates and in their vineyards. We started in California with the wines from legendary producers like Robert Mondavi, Caymus, Groth and Dunn and from the new guard like Marcassin, Peter Michael, Bryant, Colgin and Turley. We then went to France and procured wines from the big boys in Bordeaux and Burgundy – Lafite, Latour, Margaux, Mouton, DRC, Coche-Dury, Leflaive, Dujac and Drouhin. Then we moved on to the Rhone Valley, the Loire, Alsace, Champagne and the rest of France, then on to Italy, Spain, Germany, Austria, Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Northwest. So many great winemakers, so many great wines! In each place we would ask those great winemakers who, besides them, were making the best wines in the region. -

View of Race and Culture, Winter, 1957

71-27,438 BOSTICK, Herman Franklin, 1929- THE INTRODUCTION OF AFRO-FRENCH LITERATURE AND CULTURE IN THE AMERICAN SECONDARY SCHOOL . CURRICULUM: A TEACHER'S GUIDE. I The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Education, curriculum development. I i ( University Microfilms, A XEROKCompany, Ann Arbor, Michigan ©Copyright by Herman Franklin Bostick 1971 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE INTRODUCTION OF AFRO-FRENCH LITERATURE AND CULTURE IN THE AMERICAN SECONDARY SCHOOL CURRICULUM; A TEACHER'S GUIDE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Herman Franklin Bostick, B.A., M.A. The Ohio State University Approved by College of Education DEDICATION To the memory of my mother, Mrs. Leola Brown Bostick who, from my earliest introduction to formal study to the time of her death, was a constant source of encouragement and assistance; and who instilled in me the faith to persevere in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles, I solemnly dedicate this volume. H.F.B. 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To list all of the people who contributed in no small measure to the completion of this study would be impossible in the limited space generally reserved to acknowledgements in studies of this kind. Therefore, I shall have to be content with expressing to this nameless host my deepest appreciation. However, there are a few who went beyond the "call of duty" in their assistance and encouragement, not only in the preparation of this dissertation but throughout my years of study toward the Doctor of Philosophy Degree, whose names deserve to be mentioned here and to whom a special tribute of thanks must be paid. -

CLAUDIA BAEZ Paintings After Proust

ART 3 109 Ingraham Street T 646 331 3162 Brooklyn NY 11237 www.art-3gallery.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST Curated by Anne Strauss October 8 – November 22, 2014 Opening: Wednesday, October 8, 6 - 9 PM Claudia Baez, PAINTINGS after PROUST “And as she played, of all Albertine’s multiple tresses I could see but a single heart-shaped loop of black hair dinging to the side of her ear like the bow of a Velasquez Infanta.”, 2014, oil on canvas, 18 x 24 in. (45.7 x 61 cm.) © Claudia Baez Courtesy of ART 3 gallery Brooklyn, NY, September 19, 2014 – ART 3 opened in Bushwick in May 2014 near Luhring Augustine with its Inaugural Exhibition covered by The New York Times T Magazine, Primer. ART 3 was created by Silas Shabelewska-von Morisse, formerly of Haunch of Venison and Helly Nahmad Gallery. In July 2014, Monika Fabijanska, former Director of the Polish Cultural Institute in New York, joined ART 3 as Co-Director in charge of curatorial program, museums and institutions. ART 3 presents CLAUDIA BAEZ, PAINTINGS after PROUST on view at ART 3 gallery, 109 Ingraham Street, Bushwick, Brooklyn, from October 8 to November 22, 2014, Tue-Sat 12-6 PM. The opening will take place on Wednesday, October 8, from 6-9 PM. “In PAINTINGS after PROUST, Baez offers us an innovative chapter in contemporary painting in ciphering her art via a modernist work of literature within a postmodernist framework. […] In Claudia Baez’s exhibition literary narrative is poetically refracted through painting and vice versa, which the painter reminds us with artistic verve and aplomb of the adage that every picture tells a story as well as the other way around”. -

Rabelais' Pantagruel and Gargantua As Instruction Manuals

FROM POPULAR CULTURE TO ENLIGHTENMENT: RABELAIS’ PANTAGRUEL AND GARGANTUA AS INSTRUCTION MANUALS Ashley Robb A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August: 2012: Committee: Dr. Beatrice Guenther, Advisor Dr. Robert Berg ii ABSTRACT Dr. Beatrice Guenther, Advisor Popular references are a defining feature of François Rabelais’ Pantagruel and Gargantua. One cannot read either of these narratives without being exposed to a barrage of popular characters, imagery, and events. This study serves to elucidate Rabelais’ use of popular characters within Pantagruel and Gargantua by arguing that the author used these characters as instructional tools. The first component of this thesis will analyze the manner in which Rabelais makes use of his mythical protagonists in order to denounce the ideological use of myth. This study will also demonstrate how Rabelais uses popular characters in his second narrative, Gargantua, to evoke Erasmian evangelism. The final chapter of this thesis will examine several narrative techniques employed by Rabelais in order to transmit to his readers lessons on wisdom and truth. The culmination of these examples serves to show how Rabelais’ Pantagruel and Gargantua function as instruction manuals, by redefining and reclaiming what it means to be a Christian, and informing readers how to live a better, more evangelical, life. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. -

Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2000 Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust. John Stephen Larose Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Larose, John Stephen, "Memory, Time and Identity in the Novels of William Faulkner and Marcel Proust." (2000). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7206. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7206 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

An Obsession with Time in Selected Works of T

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 52 (2016) 207-215 EISSN 2392-2192 An Obsession with Time in Selected Works of T. S. Eliot as a Major Modernist Ensieh Shabanirad1,*, Ronak Ahmady Ahangar2 1Department of English Language and Literature, University of Tehran, Iran 2Department of English Language and Literature, University of Semnan, Iran *E-mail address: [email protected] ABSTRACT As a poet, Eliot seems obsessed with time: the speaker of "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock" keeps worrying about being late, and the passage of time in general as he gets older seems to continuously haunt him. In "The Waste Land" we have another form of obsession that presents itself in form of intertexuality; the many narrators of the poem go back and forth in time and provide almost random recollections of the past or haphazard bits of literary texts that are equally concerned with time. This article aims to look deeper into the importance of the concept time in Eliot's poetry, the two poems already mentioned as well as "Four Quartets" (in which a whole section is devoted to time and its philosophy) and then take the important works of other key figures of Modernism and the movement's characteristics into comparison in order to determine whether Eliot's seeming obsession is a fruit of its era or a personal motif of the poet. Keywords: T. S. Eliot; Concept of Time; Intertextuality; Modernist Poetry 1. INTRODUCTION T. S. Eliot is the well known leading figure of the Modernism movement and winner of the Nobel Prize for literature in 1948. -

New York University

New York University Spring 2020 CORE-UA 761 EXPRESSIVE CULTURES LA BELLE ÉPOQUE: PAINTING, MUSIC AND LITERATURE IN FRANCE 1852-1914 TUESDAY, THURSDAY 11-12.15 Cantor 101 Professor Thomas Ertman ([email protected]) This course takes as its subject the Belle Époque, that period in the life of France’s pre-World War I Third Republic (1871-1914) associated with extraordinary artistic achievement, as well as the Second Empire (1851-1871) that preceded it. Not only was Paris during this time the undisputed western capital of painting and sculpture, it also was the most important production site for new works of musical theater and, arguably, literature as well. It was during these decades that Impressionism launched its assault on the academic establishment, only to be superseded itself by an ever-changing avant-garde associated first with the Nabis, then with fauvism and cubism; that the operas of Bizet, Saint-Saëns and Massenet and the plays of Sardou and Rostand filled the world’s theaters; and that the novels of Zola and stories of Maupassant were translated into dozens of languages. Finally, this was the society that gave birth to one of the greatest literary works of all time, Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, the first volume of which appeared just as World War I was about to bring the Belle Époque to a violent end. In this course, we will attempt to gain a deeper understanding of the artistic works of this era by placing them in the context of the society within which they were produced, France’s Second Empire and Third Republic.