Mejia Orta, Clara.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

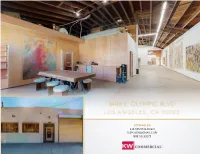

SETH POLEN 213.595.5726 Direct [email protected] DRE

SETH POLEN 213.595.5726 Direct [email protected] DRE 01133279 CONFIDENTIALITY AND DISCLAIMER All materials and information received or derived from KW COMMERCIAL its directors, officers, agents, advisors, affiliates and/or any third party sources are provided without representation or warranty as to completeness , veracity, or accuracy, condition of the property, compliance or lack of compliance with applicable governmental requirements, developability or suitability, financial performance of the property, projected financial performance of the property for any party’s intended use or any and all other matters. Neither KW COMMERCIAL its directors, officers, agents, advisors, or affiliates makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to accuracy or completeness of the materials or information provided, derived, or SETH POLEN received. Materials and information from any source, whether written or verbal, that may be furnished for review DIRECTOR are not a substitute for a party’s active conduct of its own due diligence to determine these and other matters of 213.595.5726 Direct significance to such party. KW COMMERCIAL will not investigate or verify any such matters or conduct due diligence for a party unless otherwise agreed in writing. [email protected] DRE 01133279 EACH PARTY SHALL CONDUCT ITS OWN INDEPENDENT INVESTIGATION AND DUE DILIGENCE. SETHPOLEN.COM Any party contemplating or under contract or in escrow for a transaction is urged to verify all information and to conduct their own inspections and investigations including through appropriate third party independent professionals selected by such party. All financial data should be verified by the party including by obtaining and reading applicable documents and reports and consulting appropriate independent professionals. -

Granite's Construction Experience

PUGET SOUND REGION June 8, 2010 Jim Wilkerson Purchasing Division Tacoma Public Utilities 3628 S. 35th Street Tacoma, WA 98409 RE: Statement for Qualifications for Murray Morgan Bridge Rehabilitation Design-Build Project (Specification No: PW10-0128F) Dear Jim: The rehabilitation of the Murray Morgan Bridge offers the City of Tacoma yet another creative element to the City’s infrastructure that provides beneficial use to its citizens while honoring its past. Granite Construction Company (Granite), one of the largest and most established regional and national design-build construction contractors, offers the City of Tacoma a focused team of engineers and subconsultants that has the skills, experience, and local resources to partner with the City on the delivery of this truly unique project. The Granite Team was specifically structured to deliver the most cost-effective approach to reopening the Murray Morgan Bridge by November 2012. In doing so, we are confident that we are the team best suited to: Deliver on your schedule commitments Incorporate quality systems and materials Provide the highest value for the budget Reduce operating and maintenance costs Allow for maximum supplemental work Honor stakeholder commitments To achieve these objectives, Granite has carefully selected the following key team members: FIRM ROLE Granite Construction Company Submitter, Design-Build Contractor HDR Engineering, Inc. Lead Designer (Major Participant) Kleinfelder Quality Management, Materials Testing PRR Public Involvement CivilTech Engineering Retaining Walls & Lifesafety Structures Hough Beck & Baird Urban Streetscape Design & Sustainability Link Controls Electrical Controls Design-Builder Northwest Archaeological Associates Historic/Cultural Specialist Granite / Everett Area Office | 1525 E. Marine View Dr., Everett, WA 98201-1927 | Ph: (425) 551-3100 | Fax: (425) 551-3116 Granite / Whatcom Area Office | 3876 Hannegan Rd., Bellingham, WA 98226-9103 | Ph: (360) 676-2450 | Fax: (360) 733-6735 Granite / Thurston Area Office | 7717 New Market St. -

A View of Unconcealed Alterities and Affirmations of Chicana Identity

LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 22 2013 Chicana Aesthetics: A View of Unconcealed Alterities and Affirmations of Chicana Identity through Laura Aguilar’s Photographic Images Daniel Perez California State University, Dominguez Hills, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/lux Part of the Chicano Studies Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Perez, Daniel (2013) "Chicana Aesthetics: A View of Unconcealed Alterities and Affirmations of Chicana Identity through Laura Aguilar’s Photographic Images," LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 22. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/lux/vol2/iss1/22 Perez: Unconcealed Alterities and Affirmations of Chicana Identity through Laura Aguilar’s Images Perez 1 Chicana Aesthetics: A View of Unconcealed Alterities and Affirmations of Chicana Identity through Laura Aguilar’s Photographic Images Daniel Perez California State University Dominguez Hills Abstract In this paper I will argue that Chicana feminist artist Laura Aguilar, Alma Lopez, Laura Molina, and Yreina D. Cervantez established a continuing counter-narrative of cultural hegemony and Western essentialized hegemonic identification. Through artistic expression they have developed an oppositional discourse that challenges racial stereotypes, discrimination, socio-economic inequalities, political representation, sexuality, femininity, and hegemonic discourse. I will present a complex critique of both art and culture through an inquiry of the production and evaluation of the Chicana feminist artist, their role as the artist, and their contributions to unfixing the traditional and marginalized feminine. -

GENERAL CONTRACTORS Largest Public Companies the LIST Ranked by 2020 L.A

JULY 12, 2021 LOS ANGELES BUSINESS JOURNAL 27 NEXT WEEK GENERAL CONTRACTORS Largest Public Companies THE LIST Ranked by 2020 L.A. County billings Rank Company 2020 Financials Types of Projects Current Projects Profile Top Local Executive • name (partial list) (partial list) • L.A. County • name • address Billings Contracts employees • title • website • L.A. County • L.A. County • offices • phone • U.S. • U.S. (L.A.C./total) (in millions) (in millions) • headquarters AECOM $1,393 $4,586 airports, education, Sofi Stadium, The Grand, 3545 Wilshire 225 Troy Rudd 1 300 S. Grand Ave. $10,791 NA entertainment, health care, 1 / 9 CEO Los Angeles 90071 high tech, hotel, office, Los Angeles (213) 593-8100 aecom.com parking, retail, mixed-use Swinerton Builders 1,006 3,346 airports, education, Culver Studios Office Complex – Core & Shell, TI & 1,070 Peter Ruiz 2 1150 S. Olive St., 27th Floor 5,110 13,870 entertainment, health care, Parking Structure; Dignity California Hospital and 1 / 20 Division Manager Los Angeles 90015 high tech, hotel, office, Medical Center Expansion; Westfield Topanga Center San Lia Tatevosian swinerton.com parking, retail, mixed-use Expansion; LA Union Station; TikTok Headquarters Francisco VP, Division Manager (213) 896-3400 PCL Construction Services Inc. 894 1,970 airports, education, LAX Consolidated Rent-A-Car facility, LAX Terminal 6 255 Michael Headrick 3 655 N. Central Ave., Suite 1600 2,800 7,900 entertainment, health care, Redevelopment, UCLA Southwest Campus 1 / 18 VP and District Glendale 91203 hotel, office, -

1 WS 560 Chicana Feminism Course Syllabus Class Time

WS 560 Chicana Feminism Course Syllabus Class time: MW 1:30-3:18 Phone: 247-7720 Classroom: ----- Email: [email protected] Instructor: Professor Guisela Latorre Office Hours: ------ Office: ------ Course Description This course will provide students with a general background on Chicana feminist thought. Chicana feminism has carved out a discursive space for Chicanas and other women of color, a space where they can articulate their experiences at the intersection of race, class, gender, sexuality, among other considerations. In the process, Chicana feminists have critically challenged Chicano nationalist discourse as well as European and North American feminism. This challenge has placed them in a unique albeit isolated position in relationship other established discourses about liberation and decolonization. Through this class, we will address the diversity in thinking and methodology that defines these discourses thus acknowledging the existence of a variety of feminisms that occur within Chicana intellectual thought. We will also explore the diversity of realms where this feminist thinking is applied: labor, education, cultural production (literature, art, performance, etc.), sexuality, spirituality, among others. Ultimately, we will arrive at the understanding that Chicana feminism is as much an intellectual and theoretical discourse as it is a strategy for survival and success for women of color in a highly stratified society. Each class will be composed of a lecture and discussion component. During the lecture I will cover some basic background information on Chicana feminism to provide students with the proper contextualization for the readings. After the lecture we will engage in a seminar-style discussion about the readings and their connections to the lecture material. -

806/317-0676 E-Mail: [email protected]

DR. CONSTANCE CORTEZ School of Art, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409 (cell) 806/317-0676 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: 1995 Doctor of Philosophy (Art History), University of California, Los Angeles Dissertation: "Gaspar Antonio Chi and the Xiu Family Tree" •Major: Contact Period and Colonial Art of México •Minors: Chicano/a Art, Pre-Columbian Art of México, Classical Art •Areas of Specialization: Conquest Period cultures of the Americas & colonial and postcolonial discourse 1986 Master of Arts (Art History), The University of Texas at Austin Masters Thesis: "The Principal Bird Deity in Late Preclassic & Early Classic Maya Art" •Major: Pre-Columbian Art •Minor: Latin American Studies •Area of Specialization: Classic Maya Iconography and Epigraphy 1981 Bachelor of Arts (Art History), The University of Texas at Austin TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Sept.2003- Associate Professor, Texas Tech University (Tenure/Promotion to Associate, March 6, 2009) present Graduate courses: Themes of Contemporary Art [1985-2013]; Contemporary Theory; Methodology; Memory & Art; The Body in Contemporary Art. Undergraduate courses: Themes of Contemporary Art; Contemporary Chicana/o Art; 19th-20th century Mexican Art; Colonial Art of México; Survey II [Renaissance -Impression.]; Survey III [Post Impressionism - Contemporary]. Sept.1997- Assistant Professor, Santa Clara University May 2003 Tenure-track appointment. Undergraduate: Chicana/o Art; Modern Latin American Art; Colonial Art of Mexico & Perú; Pre-Columbian Art, Native North American Art; Survey of the Arts of Oceania, Africa, & the Americas. Sept.1996- Visiting Lecturer, University of California at Santa Cruz June 1997 Nine-month appointment. Undergraduate: Chicana/o Art; Colonial Art of México; Pre-Columbian Art, Native North American Art; Survey of the Arts of Oceania, Africa, & the Americas. -

(RCAF) Chicano/A Art Collective

INTRODUCTION Mapping the Chicano/a Art History of the Royal Chicano Air Force he Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF) Chicano/a art collective pro duced major works of art, poetry, prose, music, and performance in T the United States during the second half of the twentieth century and the first decades of the twenty-first. Merging the hegemonic signs, sym bols, and texts of two nations with particular but often fragmented knowl edge of their indigenous ancestries, members of the RCAF were among a generation of Chicano/a artists in the 1960s and 1970s who revolution ized traditional genres of art through fusions of content and form in ways that continue to influence artistic practices in the twenty-first century. Encompassing artists, students, military veterans, community and labor activists, professors, poets, and musicians (and many members who identi fied with more than one of these terms), the RCAF redefined the meaning of artistic production and artwork to account for their expansive reper toire, which was inseparable from the community-based orientation of the group. The RCAF emerged in Sacramento, California, in 1969 and became established between 1970 and 1972.1 The group's work ranged from poster making, muralism, poetry, music, and performance, to a breakfast program, community art classes, and political and labor activism. Subsequently, the RCAF anticipated areas of new genre art that rely on community engage ment and relational aesthetics, despite exclusions of Chicano/a artists from these categories of art in the United States (Bourriaud 2002). Because the RCAF pushed definitions of art to include modes of production beyond tra ditional definitions and Eurocentric values, women factored significantly in the collective's output, navigating and challenging the overarching patri archal cultural norms of the Chicano movement and its manifestations in the RCAF. -

The Politics of Urban Sustainability and Environmental Justice in the Los Angeles River Watershed

Restoring a River to Reclaim a City?: The Politics of Urban Sustainability and Environmental Justice in the Los Angeles River Watershed By Esther Grace Kim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jeff Romm, Chair Professor Nancy Peluso Professor Richard Walker Fall 2017 Restoring a River to Reclaim a City?: The Politics of Urban Sustainability and Environmental Justice in the Los Angeles River Watershed Copyright © 2017 by Esther Grace Kim Abstract Restoring a River to Reclaim a City?: The Politics of Urban Sustainability and Environmental Justice in the Los Angeles River Watershed by Esther Grace Kim Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management University of California, Berkeley Professor Jeff Romm, Chair This dissertation examines the intersection of urban sustainability and environmental justice (EJ) in Los Angeles, California. ‘Urban sustainability’, the idea that incorporating sustainable measures into urban development plans/strategies can ameliorate ecological degradation and social inequality without compromising economic growth, has recently emerged as a powerful discourse with regards to city planning and environmental governance. In this dissertation, I critically interrogate urban sustainability’s claims, questioning how equitable socio-spatial configurations can be created through modes of urban governance, which despite its optimistic rhetoric, are still driven by the logic of capitalist economic development and overseen by the racial state. To investigate the ways in which environmental justice, then, is facilitated and/or constrained under the programmatic realization of urban sustainability, I focus on one particular sustainability project in Los Angeles—the restoration/revitalization of the Los Angeles River Watershed. -

Top-40-Arch-Firms.Pdf

JANUARY 26, 2015 LOS ANGELES BUSINESS JOURNAL 17 NEXT WeeK ARCHITECTURE FIRMS The Largest Motion Picture Distributors THE LIST Ranked by 2014 L.A. County billings and Largest Production Companies Rank Company L.A. County Current Projects Profile Top Local Executive THE PACESETTER: Gensler • name Billings1 (partial list) • L.A. architects • name tops the list of the largest • address • 2014 • L.A. employees2 • title architecture firms operating • website • 2013 • offices (L.A./total) • phone in L.A. County with $81 • headquarters million in billings last year. Gensler $81.1 Television Academy, Sony, LAX Midfield, Element LA, 125 John Adams/Barbara Bouza/ That’s an increase of $5.1 500 S. Figueroa St. $76.0 Metropolis, NBC Universal, JPL/NASA, Wiseburn High 279 Michael White million from 2013. The 1 Los Angeles 90071 School, Waldorf Astoria, California State University 1/46 Co-Managing Directors firm employs 279 people gensler.com N/A (213) 327-3600 dedicated to its architecture RTKL Associates Inc. 49.4 Grand Avenue Hotel and Residences, LXM Residential 47 Nate Cherry practice, including 125 2 333 S. Hope St., Suite C200 31.9 Towers, W Hotel Beijing, Eau Claire Mixed Use, ARC 232 Vice President licensed architects, in its Los Angeles 90071 Centre Plaza, Wuxi Suning 1/15 (213) 633-6000 downtown Los Angeles rtkl.com Baltimore office. Aecom Technology Corp. 38.0 New Face of the Central Terminal Area, Midfield Satellite 13 Ross Wimer 515 S. Flower St. 16.5 Concourse, San Diego Airport Parking Plaza, Downtown 26 Senior Vice President 3 Los Angeles 90071 Harbor, Glendale Narrows Phase 1, San Pedro 14/923 (213) 593-8000 aecom.com/architecture Waterfront Master Plan Los Angeles ZGF Architects 35.1 California Science Center, UCLA Wasserman Football 30 Ted Hyman 515 S. -

Milwaukee Police Department

MILWAUKEE POLICE DEPARTMENT MILWAUKEE POLICE DEPARTMENT HEADQUARTERS 935 North Eighth Street Miiwaukee 3, Wisconsin ANNUAL REPOR'I 1956 TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary of Department Activities 1-2 New Innovations 3 .Pe-1"--sennel and Salal'y Scal-e , Me-mbe-rs--of the- Dep-t., 1-'a-ble !-A 4-5-6-7-8-9 Organization Chart 10 Personnel Distribution of Dept., Table I-B 11 Changes in Authorized and Actual Strength, Table II 12 Changes in Personnel, Table II-A 13 Report of Police Physicians , Table III 14 Urinalysis , Table III-A 14 Offenses Known to the Police, Table IV 15 Adult Arrests and Juvenile Detentions , Table V 16 Monthly Statement of Arrests , Table VI 17 Adult Arrests, Table VII 18 Nativity Age Domestic Status Color Detective Bureau 19 Auto Theft Statistics, Suicides, Sudden Death, etc . , Table VIII 19 Bureau of Identification 20 Youth Aid Bureau 20 Police Training School 21 Communications Bureau 21 Traffic Bureau 22 Vice Squad 22 Property Bureau 23 Homicides 24-25 Miscellaneous Services, Table X 26 Distribution of Plant Equipment, Table .XI-A 27 Police Department Expenditures, Table XI-B 28 Cash Receipts by Police District, Table XI-C 28 Traffic Accidents Analysis of Traffic Accidents - 1956, Table XII-A 29 Persons Killed, Table XII-B 30 Persons Injured, Table XII-C 31 By Hour of Day, Table XII-D 32 By Day of Week, Table XII-E 33 Light Conditions, Table XII-F 33 Type of Vehicle , Table XII-G 33 Pedestrian Accidents , Table XII-H 34 Summary of All Traffic Accidents Reported, Table XII-I 35 Comparison of Motor Vehicle Fatalities and Motor Vehicle Registration, Table XII-J 36 Official Citations - 1956 37-38 Chiefs of Police 39 Obituary 39 Pictorial Review of Spe~ial Events - 19 56 40 DED ICAT ION The merits of. -

50 DI Sixth Street Viaduct.Indd

INDUSTRY INNOVATION Busy on set Los Angeles replaces famous Hollywood backdrop By Vic Martinez and Michael Jones Often seen looming above riverbed car In 2004, a seismic vulnerability study Contributing Authors chases along the Los Angeles River, the bridge, was conducted that concluded the weak- like many celebrities, is more complicated ened state of the 3,500-ft viaduct put it at ne of America’s most famous underneath the surface than the public persona high risk for failure in a major earthquake. it has projected since it was built in 1932. Due to the viaduct’s geometric design and and recognizable bridges, the When the bridge was just 20 years old, safety deficiencies, the city of Los Angeles’ O Sixth Street Viaduct, has been its concrete supports began to disintegrate, Bureau of Engineering now had a convinc- caused by a chemical reaction known as alkali ing argument for replacing the bridge. used to represent Los Angeles’ more gritty silica reaction. Over the years, costly restor- What they didn’t have was a replacement side in countless movies, music videos ative measures attempted to save the structure, design concept that would be worthy of but none worked. the iconic viaduct. and TV commercials. 50 August 2015 • ROADS&BRIDGES ROADSBRIDGES.com 51 “The Ribbon of Light” features 10 pairs of arches, canted at 9°, forming a single stress ribbon running the whole length of the viaduct. The initiative to build a new bridge to list: AECOM, HNTB Corp. and Parsons Vic Martinez, HNTB’s project manager, replace the structure drew worldwide atten- Brinckerhoff. -

“The Whiteness Project of Gentrification: the Battle Over Los

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2018 The Whiteness Project of Gentrification: The Battle vo er Los Angeles' Eastside Jaime Guzmán University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Ethnic Studies Commons, and the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons Recommended Citation Guzmán, Jaime, "The Whiteness Project of Gentrification: The Battle over Los Angeles' Eastside" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1433. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1433 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. THE WHITENESS PROJECT OF GENTRIFICATION: THE BATTLE OVER LOS ANGELES’ EASTSIDE __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Jaime Guzmán June 2018 Advisor: Armond Towns ©Copyright by Jaime Guzmán 2018 All Rights Reserved Author: Jaime Guzmán Title: THE WHITENESS PROJECT OF GENTRIFICATION: THE BATTLE OVER LOS ANGELES’ EASTSIDE Advisor: Armond Towns Degree Date: June 2018 ABSTRACT For many years, the city of Los Angeles has declared war on communities of color. In the past decade, former communities of color like Echo Park, Silver Lake, and Highland Park have all been converted into predominantly white, affluent neighborhoods. In essence, working-class people of colors’ neighborhoods are being uplifted in order to welcome a much more affluent population to town.