(RCAF) Chicano/A Art Collective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Cary Cordova 2005

Copyright by Cary Cordova 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Cary Cordova Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE HEART OF THE MISSION: LATINO ART AND IDENTITY IN SAN FRANCISCO Committee: Steven D. Hoelscher, Co-Supervisor Shelley Fisher Fishkin, Co-Supervisor Janet Davis David Montejano Deborah Paredez Shirley Thompson THE HEART OF THE MISSION: LATINO ART AND IDENTITY IN SAN FRANCISCO by Cary Cordova, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2005 Dedication To my parents, Jennifer Feeley and Solomon Cordova, and to our beloved San Francisco family of “beatnik” and “avant-garde” friends, Nancy Eichler, Ed and Anna Everett, Ellen Kernigan, and José Ramón Lerma. Acknowledgements For as long as I can remember, my most meaningful encounters with history emerged from first-hand accounts – autobiographies, diaries, articles, oral histories, scratchy recordings, and scraps of paper. This dissertation is a product of my encounters with many people, who made history a constant presence in my life. I am grateful to an expansive community of people who have assisted me with this project. This dissertation would not have been possible without the many people who sat down with me for countless hours to record their oral histories: Cesar Ascarrunz, Francisco Camplis, Luis Cervantes, Susan Cervantes, Maruja Cid, Carlos Cordova, Daniel del Solar, Martha Estrella, Juan Fuentes, Rupert Garcia, Yolanda Garfias Woo, Amelia “Mia” Galaviz de Gonzalez, Juan Gonzales, José Ramón Lerma, Andres Lopez, Yolanda Lopez, Carlos Loarca, Alejandro Murguía, Michael Nolan, Patricia Rodriguez, Peter Rodriguez, Nina Serrano, and René Yañez. -

Points of Convergence Puntos De Convergencia

POINTS OF CONVERGENCE The Iconography of the Chicano Poster Tere Romo The concept of national identity refers loosely to a field of social representation in which the battles and symbolic synthesis between different memories and collective projects takes place. G ABRIEL P ELUFFO l 1NARI 1 + El concepto de identidad nacional se refiere en general a un campo de representaci6n social en que tienen Iugar las luchas y las sintesis simb61icas de diferentes memorias y proyectos colectivos. G ABR I EL P ELUFFO L INARI Tere Romo PUNTOS DE CONVERGENCIA La iconografia del cartel chicano The Chicano Movement of the late 1960s and El movimiento chicano de finales de los anos 60 1970s marked the beginning of Chicano art. It was y 70 marco el inicio del arte chicano. Fue dentro de within this larger movement for civil and cultural este movimiento mas am plio de derechos civiles y rights that many Chicano/a artists chose to utilize culturales que muchos artistas chicanos y chicanas their art-making to further the formation of cultural utilizaron su arte para avanzar Ia formacion de iden ti identity and political unity, as reflected in their dad cultural y unidad politica, como queda reflejado er choice of content, symbols, and media. As expressed su eleccion de contenido, simbolos y medias. Como in the seminal El Plan Espiritual de Aztltin expresa El Plan Espiritual de Azt/6n, redactado en Ia {Spiritual Plan of Aztltin}, drafted at the 1969 Conferencia Juvenil para Ia Liberacion Nacional Chicano National Liberation Youth Conference in Chicana (Chicano -

Southern California Artists Challenge America Paul Von Blum After the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001, America Experienc

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 20 (2004) : 17-27 Southern California Artists Challenge America Paul Von Blum After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, America experienced an outpouring of international sympathy. Political leaders and millions of people throughout the world expressed heartfelt grief for the great loss of life in the wake of the unspeakable horror at the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and in Pennsylvania. Four years later, America has had its world standing and moral credibility substantially reduced. In striking contrast to the immediate aftermath of 9/11, it faces profound isolation and disrespect throughout the world. The increasingly protracted war in Iraq has been the major catalyst for massive international disapproval. Moreover, the arrogance of the George W. Bush administration in world affairs has alienated many of America’s traditional allies and has precipitated widespread global demonstrations against its policies and priorities. Domestically, the Bush presidency has galvanized enormous opposition and has divided the nation more deeply than any time since the height of the equally unpopular war in Vietnam. Dissent against President Bush and his retrograde socio-economic agenda has become a powerful force in contemporary American life. Among the most prominent of those commenting upon American policies have been members of the artistic community. Musicians, writers, filmmakers, actors, dancers, visual artists, and other artists continue a long-held practice of using their creative talents to call dramatic attention to the enormous gap between American ideals of freedom, justice, equality, and peace and American realities of racism, sexism, and international aggression. In 2004, for example, Michael Moore’s film “Fahrenheit 9/11,” which is highly critical of President Bush, has attracted large audiences in the United States and abroad. -

Poster Power: the Dramatic Impact of Political Art

Poster Power: The Dramatic Impact of Political Art truthdig.com/articles/poster-power-dramatic-impact-political-art/ Poster Power: The Dramatic Impact of Political Art From "In Solidarity With Standing Rock," a 2016 poster by Josh Yoder. (Center for the Study of Political Graphics) See Truthdig’s photo essay depicting posters from the exhibition. In recent years, the shocking murders of unarmed African-Americans at the hands of police have horrified people throughout the nation and the world. The killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., Eric Garner in New York City, Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Laquan McDonald in Chicago, Oscar Grant in Oakland, Calif., Walter Scott in North Charleston, S.C., and many others reveal the horrific pattern of police brutality and misconduct in the United States. The mysterious deaths of Freddie Gray in Baltimore after a rough ride in a police van and Sandra Bland’s so-called suicide in a Texas jailhouse only underscore the dangers that people of color have faced from police authorities for centuries. Most of these atrocities are well known because of extensive media coverage. Still, the public 1/4 should be reminded of the deeper historical roots of these tragic events in order to place them into a coherent yet disconcerting context. In that vein, two venerable Los Angeles public arts organizations have collaborated to present one of the most powerful and effective political art exhibitions in recent years. The Center for the Study of Political Graphics has organized an exhibit drawn from its massive collection of political posters, the most recent of 30 years of distinguished poster exhibitions on multiple themes (see Truthdig’s accompanyingphoto essay with posters from the exhibit.) The show, which opened Dec. -

Ricardo Favela Royal Chicano Air Force Poster Collection MSS.2005.11.01

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1v19r5t3 No online items Guide to the Ricardo Favela Royal Chicano Air Force Poster Collection MSS.2005.11.01 Elizabeth Lopez Finding aid funded by the generous support of the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC). SJSU Special Collections & Archives © 2009 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Library San José State University One Washington Square San José, CA 95192-0028 [email protected] URL: http://library.sjsu.edu/sjsu-special-collections/sjsu-special-collections-and-archives Guide to the Ricardo Favela Royal MSS.2005.11.01 1 Chicano Air Force Poster Collection MSS.2005.11.01 Language of Material: Spanish; Castilian Contributing Institution: SJSU Special Collections & Archives Title: Ricardo Favela Royal Chicano Air Force Poster Collection creator: Royal Chicano Air Force source: Favela, Ricardo Identifier/Call Number: MSS.2005.11.01 Physical Description: 13 folders(192 posters) Date (inclusive): 1971-2005 Abstract: The Royal Chicano Air Force Poster Collection consists of 192 posters for community-based programs and events held by the city of Sacramento and students from California State University, Sacramento. Language of Material: Posters are in English and Spanish. Access The collection is open for research. Publication Rights Ricardo Favela has assigned copyright to the San José State University Library Special Collections & Archives where he is the copyright holder. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Director of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Special Collections & Archives as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which must also be obtained by the reader. -

A View of Unconcealed Alterities and Affirmations of Chicana Identity

LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 22 2013 Chicana Aesthetics: A View of Unconcealed Alterities and Affirmations of Chicana Identity through Laura Aguilar’s Photographic Images Daniel Perez California State University, Dominguez Hills, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/lux Part of the Chicano Studies Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Perez, Daniel (2013) "Chicana Aesthetics: A View of Unconcealed Alterities and Affirmations of Chicana Identity through Laura Aguilar’s Photographic Images," LUX: A Journal of Transdisciplinary Writing and Research from Claremont Graduate University: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 22. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/lux/vol2/iss1/22 Perez: Unconcealed Alterities and Affirmations of Chicana Identity through Laura Aguilar’s Images Perez 1 Chicana Aesthetics: A View of Unconcealed Alterities and Affirmations of Chicana Identity through Laura Aguilar’s Photographic Images Daniel Perez California State University Dominguez Hills Abstract In this paper I will argue that Chicana feminist artist Laura Aguilar, Alma Lopez, Laura Molina, and Yreina D. Cervantez established a continuing counter-narrative of cultural hegemony and Western essentialized hegemonic identification. Through artistic expression they have developed an oppositional discourse that challenges racial stereotypes, discrimination, socio-economic inequalities, political representation, sexuality, femininity, and hegemonic discourse. I will present a complex critique of both art and culture through an inquiry of the production and evaluation of the Chicana feminist artist, their role as the artist, and their contributions to unfixing the traditional and marginalized feminine. -

SERNA SUPERVISOR, FIRST DISTRICT Telephone (916) 874-5485 FAX (916) 874-7593 BOARD of SUPERVISORS E-Mail [email protected] COUNTY of SACRAMENTO

PHIL SERNA SUPERVISOR, FIRST DISTRICT Telephone (916) 874-5485 FAX (916) 874-7593 BOARD OF SUPERVISORS E-Mail [email protected] COUNTY OF SACRAMENTO 700 H STREET, SUITE 2450, SACRAMENTO, CA 95814 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Lisa Nava, Chief of Staff February 28, 2018 [email protected] 916.874.5485 Supervisor Serna, Royal Chicano Air Force and Sacramento Kings to dedicate new mural “Flight” at Golden 1 Center Sacramento, CA – This Thursday, March 1 at the Golden 1 Center, Sacramento County Supervisor Phil Serna, The Sacramento Kings, and founding members of the local art collective The Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF), will dedicate a new panel mural public art installation titled “Flight.” According to the artwork’s project manager, RCAF co-founder Juan Carrillo, “The 27x11-foot, three- paneled mural tells the story of humankind's multi-generational evolution from Quetzalcoatl to El Sexto Sol, The Sixth Sun.” Carrillo adds, “The art work is an RCAF legacy piece for our home community reflecting who we are and what we value.” The project idea came from Sacramento County Supervisor Phil Serna who wanted to acknowledge the RCAF's profound legacy. Serna, the son of the late Joe Serna, Jr. – an RCAF co-founder and Sacramento's first Latino Mayor – also assembled the funding to make the project possible. Serna’s office commissioned the work in coordination with the Sacramento Metropolitan Arts Commission and City of Sacramento, owner of the Golden 1 Center arena. “The Royal Chicano Air Force significantly shaped who I am today especially the intersection of expression and activism, and the obligation to pursue social justice, which I think more and more elected people should hone these days,” says Serna. -

1 WS 560 Chicana Feminism Course Syllabus Class Time

WS 560 Chicana Feminism Course Syllabus Class time: MW 1:30-3:18 Phone: 247-7720 Classroom: ----- Email: [email protected] Instructor: Professor Guisela Latorre Office Hours: ------ Office: ------ Course Description This course will provide students with a general background on Chicana feminist thought. Chicana feminism has carved out a discursive space for Chicanas and other women of color, a space where they can articulate their experiences at the intersection of race, class, gender, sexuality, among other considerations. In the process, Chicana feminists have critically challenged Chicano nationalist discourse as well as European and North American feminism. This challenge has placed them in a unique albeit isolated position in relationship other established discourses about liberation and decolonization. Through this class, we will address the diversity in thinking and methodology that defines these discourses thus acknowledging the existence of a variety of feminisms that occur within Chicana intellectual thought. We will also explore the diversity of realms where this feminist thinking is applied: labor, education, cultural production (literature, art, performance, etc.), sexuality, spirituality, among others. Ultimately, we will arrive at the understanding that Chicana feminism is as much an intellectual and theoretical discourse as it is a strategy for survival and success for women of color in a highly stratified society. Each class will be composed of a lecture and discussion component. During the lecture I will cover some basic background information on Chicana feminism to provide students with the proper contextualization for the readings. After the lecture we will engage in a seminar-style discussion about the readings and their connections to the lecture material. -

806/317-0676 E-Mail: [email protected]

DR. CONSTANCE CORTEZ School of Art, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409 (cell) 806/317-0676 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: 1995 Doctor of Philosophy (Art History), University of California, Los Angeles Dissertation: "Gaspar Antonio Chi and the Xiu Family Tree" •Major: Contact Period and Colonial Art of México •Minors: Chicano/a Art, Pre-Columbian Art of México, Classical Art •Areas of Specialization: Conquest Period cultures of the Americas & colonial and postcolonial discourse 1986 Master of Arts (Art History), The University of Texas at Austin Masters Thesis: "The Principal Bird Deity in Late Preclassic & Early Classic Maya Art" •Major: Pre-Columbian Art •Minor: Latin American Studies •Area of Specialization: Classic Maya Iconography and Epigraphy 1981 Bachelor of Arts (Art History), The University of Texas at Austin TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Sept.2003- Associate Professor, Texas Tech University (Tenure/Promotion to Associate, March 6, 2009) present Graduate courses: Themes of Contemporary Art [1985-2013]; Contemporary Theory; Methodology; Memory & Art; The Body in Contemporary Art. Undergraduate courses: Themes of Contemporary Art; Contemporary Chicana/o Art; 19th-20th century Mexican Art; Colonial Art of México; Survey II [Renaissance -Impression.]; Survey III [Post Impressionism - Contemporary]. Sept.1997- Assistant Professor, Santa Clara University May 2003 Tenure-track appointment. Undergraduate: Chicana/o Art; Modern Latin American Art; Colonial Art of Mexico & Perú; Pre-Columbian Art, Native North American Art; Survey of the Arts of Oceania, Africa, & the Americas. Sept.1996- Visiting Lecturer, University of California at Santa Cruz June 1997 Nine-month appointment. Undergraduate: Chicana/o Art; Colonial Art of México; Pre-Columbian Art, Native North American Art; Survey of the Arts of Oceania, Africa, & the Americas. -

The Place of Chicana Feminism and Chicano Art in the History

THE PLACE OF CHICANA FEMINISM AND CHICANO ART IN THE HISTORY CURRICULUM A Project Presented to the faculty of the Department of History California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History by Beatriz Anguiano FALL 2012 © 2012 Beatriz Anguiano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii THE PLACE OF CHICANA FEMINISM AND CHICANO ART IN THE HISTORY CURRICULUM A Project by Beatriz Anguiano Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Chloe S. Burke __________________________________, Second Reader Donald J. Azevada, Jr. ____________________________ Date \ iii Student: Beatriz Anguiano I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. __________________________, Chair ___________________ Mona Siegel, PhD Date Department of History iv Abstract of THE PLACE OF CHICANA FEMINISM AND CHICANO ART IN THE HISTORY CURRICULUM by Beatriz Anguiano Statement of Problem Chicanos are essentially absent from the State of California United States History Content Standards, as a result Chicanos are excluded from the narrative of American history. Because Chicanos are not included in the content standards and due to the lack of readily available resources, this presents a challenge for teachers to teach about the role Chicanos have played in U.S. history. Chicanas have also largely been left out of the narrative of the Chicano Movement, also therefore resulting in an incomplete history of the Chicano Movement. This gap in our historical record depicts an inaccurate representation of our nation’s history. -

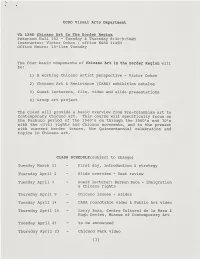

UCSD Visual Arts Department VA 128D Chicano Art

- UCSD Visual Arts Department VA 128D Chicano Art In The Border Region Peterson Hall 102 - Tuesday & Thursday 8:30-9:50AM Instructor: Victor Ochoa / office H&SS 1145D Office Hours: 10-11am Tuesday The four basic components of Chicano Art in the Border Region will be: 1) A working Chicano artist perspective - Victor Ochoa 2) Chicano Art & Resistance (CARA) exhibition catalog 3) Guest lecturers, film, video and slide presentations 4) Group art project The class will provide a basic overview from Pre-Colombian art to Contemporary Chicano art. This course will specifically focus on the Pachuco period of the 1940's on through the 1960's and 70's with the civil rights and Chicano movements, and to the present with current border issues, the Quincentennial celebration and topics in Chicana art. CLASS SCHEDULE(subject to change) Tuesday March 31 First day, introduction & strategy Thursday April 2 Slide overview - Text review Tuesday April 7 Guest lecturer: Herman Baca - immigration & Chicano rights Thursday April 9 - Chicano issues - slides Tuesday April 14 - CARA roundtable video & Public Art video Thursday April 16 - Larry Baza, Centro Cultural de la Raza & Hugh Davies, Museum of Contemporary Art Tuesday April 21 - to be announced Thursday April 23 - Chicano Park video [1] VA 128D(cont.) Saturday April 25 - Chicano Park Day - required field trip Tuesday April 28 - Issac Artenstein - "Mi Otro Yo" & video potpourri Thursday April 30 - Ireina Cervantes: personal work, Chicanas & Frida (Midterm due) Tuesday May 5 - David Avalos & BAW/TAF the -

Jose Montoya Dies at 81; Leading Figure in California Latino Culture - Lat

Jose Montoya dies at 81; leading figure in California Latino culture - lat... http://www.latimes.com/obituaries/la-me-jose-montoya-20131005,0,370... latimes.com/obituaries/la-me-jose-montoya-20131005,0,7872380.story Jose Montoya, the former Sacramento poet laureate, became a leading figure in California Latino culture of the post-World War II era. By Reed Johnson 8:43 PM PDT, October 4, 2013 The little farm towns of Central California held a poetry all their own for Jose Montoya. advertisement From childhood he knew their people, mostly immigrant laborers like his own family. He knew the labyrinthine rows of fruit trees, the dirt-floor houses and trailer camps. He knew the hardship and humanity of places named Del Rey and Fowler and Laton, Yuba City and Delano. "He just marveled that they had such a singsongy ring to them," said the poet's son, actor-playwright Richard Montoya of the L.A. performance group Culture Clash. As a man, Jose Montoya would translate his knowledge and affection for those landscapes and their campesino residents into poems like "The Resonant Valley" and "El Sol y Los de Abajo" — The Sun and Those Below, or, colloquially, the Underdogs — as well as into drawings, prints and paintings etched in fierce empathy. He also would channel his awareness of migrant workers' harsh living conditions into a lifetime of political activism and union organizing that would link his name with those of close friends like Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, co-founders of the United Farm Workers. And he would synthesize his various roles and concerns — community organizer, Chicano-rights advocate, Central Valley bard — as a co-founder of the Rebel Chicano Art Front (RCAF), the slyly subversive Sacramento art collective later re-christened the Royal Chicano Air Force.