Review Four Los Angeles Exhibits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Points of Convergence Puntos De Convergencia

POINTS OF CONVERGENCE The Iconography of the Chicano Poster Tere Romo The concept of national identity refers loosely to a field of social representation in which the battles and symbolic synthesis between different memories and collective projects takes place. G ABRIEL P ELUFFO l 1NARI 1 + El concepto de identidad nacional se refiere en general a un campo de representaci6n social en que tienen Iugar las luchas y las sintesis simb61icas de diferentes memorias y proyectos colectivos. G ABR I EL P ELUFFO L INARI Tere Romo PUNTOS DE CONVERGENCIA La iconografia del cartel chicano The Chicano Movement of the late 1960s and El movimiento chicano de finales de los anos 60 1970s marked the beginning of Chicano art. It was y 70 marco el inicio del arte chicano. Fue dentro de within this larger movement for civil and cultural este movimiento mas am plio de derechos civiles y rights that many Chicano/a artists chose to utilize culturales que muchos artistas chicanos y chicanas their art-making to further the formation of cultural utilizaron su arte para avanzar Ia formacion de iden ti identity and political unity, as reflected in their dad cultural y unidad politica, como queda reflejado er choice of content, symbols, and media. As expressed su eleccion de contenido, simbolos y medias. Como in the seminal El Plan Espiritual de Aztltin expresa El Plan Espiritual de Azt/6n, redactado en Ia {Spiritual Plan of Aztltin}, drafted at the 1969 Conferencia Juvenil para Ia Liberacion Nacional Chicano National Liberation Youth Conference in Chicana (Chicano -

Extensions of Remarks 1635 H

January 28, 1975 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 1635 H. Res. 103. Resolution expressing the m.itted by the Secretary of the Interior, pur By Mr. CONTE: sense of the House that the U.S. Government suant to the provisions of the act of October H.R. 2279. A bill for the relief of Mrs. Louise should seek agreement with other members 19, 1973 (87 Stat. 466), providing for the G. Whalen; to the Committee on the Judi of the United Nations on prohibition of distribution of funds appropriated in satis ciary. weather modification activity as a weapon of faction of an award of the Indian Claims By Mr. HELSTOSKI: war; to the Committee on Foreign Affairs. Commission to the Cowlitz Tribe of Indians H.R. 2280. A bill for the relief of Mr. and By Mr. HENDERSON (for himself and in docket No. 218; to the Committee on In 1\:!rs. Luis (Maria) Echavarria; to the Com Mr. DER~SKI) : terior and Insular Affairs. mittee on the Judiciary. H. Res. 104. Resolution to provide funds By Mr. PEYSER (for himself, Mr. By Mr. McCLOSKEY: for the expenses of the investigation and WmTH, and Mr. OTTINGER): H.R. 2281. A bill for the relief of Kim Ung study authorized by House Rule XI; to the H. Res. 108. Resolution expressing the sense Nyu; to the Committee on the Judiciary. Committee on House Administration. of the House that the Secretary of Agriculture H.R. 2282. A bill for the relief of Lee-Daniel By Mrs. HOLT: should rescind the food stamp regulations Alexander; to the Committee on the Judici H. -

Southern California Artists Challenge America Paul Von Blum After the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001, America Experienc

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 20 (2004) : 17-27 Southern California Artists Challenge America Paul Von Blum After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, America experienced an outpouring of international sympathy. Political leaders and millions of people throughout the world expressed heartfelt grief for the great loss of life in the wake of the unspeakable horror at the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and in Pennsylvania. Four years later, America has had its world standing and moral credibility substantially reduced. In striking contrast to the immediate aftermath of 9/11, it faces profound isolation and disrespect throughout the world. The increasingly protracted war in Iraq has been the major catalyst for massive international disapproval. Moreover, the arrogance of the George W. Bush administration in world affairs has alienated many of America’s traditional allies and has precipitated widespread global demonstrations against its policies and priorities. Domestically, the Bush presidency has galvanized enormous opposition and has divided the nation more deeply than any time since the height of the equally unpopular war in Vietnam. Dissent against President Bush and his retrograde socio-economic agenda has become a powerful force in contemporary American life. Among the most prominent of those commenting upon American policies have been members of the artistic community. Musicians, writers, filmmakers, actors, dancers, visual artists, and other artists continue a long-held practice of using their creative talents to call dramatic attention to the enormous gap between American ideals of freedom, justice, equality, and peace and American realities of racism, sexism, and international aggression. In 2004, for example, Michael Moore’s film “Fahrenheit 9/11,” which is highly critical of President Bush, has attracted large audiences in the United States and abroad. -

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set the Following Players Comprise the 1960 Season APBA Football Player Card Set

APBA 1960 Football Season Card Set The following players comprise the 1960 season APBA Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. BALTIMORE 6-6 CHICAGO 5-6-1 CLEVELAND 8-3-1 DALLAS (N) 0-11-1 Offense Offense Offense Offense Wide Receiver: Raymond Berry Wide Receiver: Willard Dewveall Wide Receiver: Ray Renfro Wide Receiver: Billy Howton Jim Mutscheller Jim Dooley Rich Kreitling Fred Dugan (ET) Tackle: Jim Parker (G) Angelo Coia TC Fred Murphy Frank Clarke George Preas (G) Bo Farrington Leon Clarke (ET) Dick Bielski OC Sherman Plunkett Harlon Hill A.D. Williams Dave Sherer PA Guard: Art Spinney Tackle: Herman Lee (G-ET) Tackle: Dick Schafrath (G) Woodley Lewis Alex Sandusky Stan Fanning Mike McCormack (DT) Tackle: Bob Fry (G) Palmer Pyle Bob Wetoska (G-C) Gene Selawski (G) Paul Dickson Center: Buzz Nutter (LB) Guard: Stan Jones (T) Guard: Jim Ray Smith(T) Byron Bradfute Quarterback: Johnny Unitas Ted Karras (T) Gene Hickerson Dick Klein (DT) -

Poster Power: the Dramatic Impact of Political Art

Poster Power: The Dramatic Impact of Political Art truthdig.com/articles/poster-power-dramatic-impact-political-art/ Poster Power: The Dramatic Impact of Political Art From "In Solidarity With Standing Rock," a 2016 poster by Josh Yoder. (Center for the Study of Political Graphics) See Truthdig’s photo essay depicting posters from the exhibition. In recent years, the shocking murders of unarmed African-Americans at the hands of police have horrified people throughout the nation and the world. The killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., Eric Garner in New York City, Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Laquan McDonald in Chicago, Oscar Grant in Oakland, Calif., Walter Scott in North Charleston, S.C., and many others reveal the horrific pattern of police brutality and misconduct in the United States. The mysterious deaths of Freddie Gray in Baltimore after a rough ride in a police van and Sandra Bland’s so-called suicide in a Texas jailhouse only underscore the dangers that people of color have faced from police authorities for centuries. Most of these atrocities are well known because of extensive media coverage. Still, the public 1/4 should be reminded of the deeper historical roots of these tragic events in order to place them into a coherent yet disconcerting context. In that vein, two venerable Los Angeles public arts organizations have collaborated to present one of the most powerful and effective political art exhibitions in recent years. The Center for the Study of Political Graphics has organized an exhibit drawn from its massive collection of political posters, the most recent of 30 years of distinguished poster exhibitions on multiple themes (see Truthdig’s accompanyingphoto essay with posters from the exhibit.) The show, which opened Dec. -

History and Results

H DENVER BRONCOS ISTORY Miscellaneous & R ESULTS Year-by-Year Stats Postseason Records Honors History/Results 252 Staff/Coaches Players Roster Breakdown 2019 Season Staff/Coaches Players Roster Breakdown 2019 Season DENVER BRONCOS BRONCOS ALL-TIME DRAFT CHOICES NUMBER OF DRAFT CHOICES PER SCHOOL 20 — Florida 15 — Colorado, Georgia 14 — Miami (Fla.), Nebraska 13 — Louisiana State, Houston, Southern California 12 — Michigan State, Washington 11 — Arkansas, Arizona State, Michigan 10 — Iowa, Notre Dame, Ohio State, Oregon 9 — Maryland, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Purdue, Virginia Tech 8 — Arizona, Clemson, Georgia Tech, Minnesota, Syracuse, Texas, Utah State, Washington State 7 — Baylor, Boise State, Boston College, Kansas, North Carolina, Penn State. 6 — Alabama, Auburn, Brigham Young, California, Florida A&M, Northwestern, Oklahoma State, San Diego, Tennessee, Texas A&M, UCLA, Utah, Virginia 5 — Alcorn State, Colorado State, Florida State, Grambling, Illinois, Mississippi State, Pittsburgh, San Jose State, Texas Christian, Tulane, Wisconsin 4 — Arkansas State, Bowling Green/Bowling Green State, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa State, Jackson State, Kansas State, Kentucky, Louisville, Maryland-Eastern Shore, Miami (Ohio), Missouri, Northern Arizona, Oregon State, Pacific, South Carolina, Southern, Stanford, Texas A&I/Texas A&M Kingsville, Texas Tech, Tulsa, Wyoming 3 — Detroit, Duke, Fresno State, Montana State, North Carolina State, North Texas State, Rice, Richmond, Tennessee State, Texas-El Paso, Toledo, Wake Forest, Weber State 2 — Alabama A&M, Bakersfield -

FALL 2016 JORDAN SCHNITZER MUSEUM of ART Robert Rauschenberg (American, 1925– SCRIMMAGE: 2008)

FALL 2016 JORDAN SCHNITZER MUSEUM OF ART Robert Rauschenberg (American, 1925– SCRIMMAGE: 2008). Junction, 1963. Oil and silkscreen on canvas and metal, 45 1/2 x 61 1/2 inches. Football in American Art from the Civil War to the Present Collection of Christopher Rauschenberg. Art © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation/ Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Barker Gallery | Through December 31 What do Winslow Homer, George Bellows, at the youth and high school levels) in which the Laura Gilpin, John Steuart Curry, Andy Warhol, artist, serving as the “matador,” is surrounded by Wayne Thiebaud, Catherine Opie, and Diego a revolving circle of semi-pro players who charge Romero all have in common? They, and nearly without warning from all sides. Leonardo experienced fifty other artists whose works are on view in this the drill as a football player at Bowdoin College in the special exhibition, have depicted football and the late 1990s, and in a 2008 interview at his alma mater he explained that “my intention is to perform an public culture surrounding the sport. Scrimmage— Curator’s Gallery Tour Native American Studies, in issues of brain trauma, he organized by Linny Frickman, director of the Gregory aesthetically scripted yet actual Bull in the Ring with Wednesday, September 14, Native American Student turned his attention to the Allicar Museum of Art at Colorado State University, an undetermined outcome [where] I, as the center 5:30 p.m. Union, and Native American history of images and how and Danielle Knapp, McCosh Associate Curator at participant, will either affirm my virility or fail; in Danielle Knapp, McCosh Law Student Association. -

Visual Art Activity Guide 2017-2018 Pro Football Hall of Fame 2017-2018 Educational Outreach Program Visual Art Table of Contents

Pro Football Hall of Fame Youth & Education Visual Art Activity Guide 2017-2018 Pro Football Hall of Fame 2017-2018 Educational Outreach Program Visual Art Table of Contents Lesson National Standards Page(s) Hands of Many Colors 1 - Understand/Apply VA 1 Create a Football Card 1 - Understand/Apply VA 2-3 Drawing a Cartoon Football Player 1 - Understand/Apply VA 4-5 Ernie Barnes: Athlete and Sports Artist 4 - History/Culture VA 6-7 Football Field in One-Point Perspective 1 - Understand/Apply, 2 - Structures VA 8-9 1 - Understand/Apply, 2 - Structures, Football Hero 3 - Evaluate VA 10-11 Football Themed Action Figures 1 - Understand/Apply VA 12-13 Football Themed Tessellations 1 - Understand/Apply VA 14-15 Gear for Spectators 1 - Understand/Apply VA 16-17 Designer Cleats 1 - Understand/Apply VA 18-19 Jersey Design 1 - Understand/Apply VA 20-21 Jewelry Design: Create Your Own Super Bowl Ring 3 - Evaluate VA 22-23 LeRoy Neiman, Sports Painter 4 - History/Culture VA 24-25 Photographer VA 26 Nametags VA 27 Pennant VA 28 Visual Art Hands of Many Colors Goals/Objectives: Students will: • Reinforce visual awareness of hand shape, skin color, value and overlapping National Standards: 1-Understanding and applying media, techniques, and processes Methods/Procedures: • Students may orient paper horizontally or vertically. Present them with the challenge of drawing an action picture featuring hands and forearms of football players. In order to ac- complish this, younger students may trace their hands, while intermediate elementary and middle school artists will likely chose to create freehand drawings by observing their own hands. -

The Studio Museum in Harlem Ma∂Azine/Summer 2009

Studio/ Summer 2009 The Studio Museum in Harlem Ma∂azine/ Summer 2009 James VanDerZee / Barefoot Prophet / 1929 / Courtesy Donna Mussenden The Studio Museum in Harlem Ma∂azine / 2009–10 02 What’s Up / Hurvin Anderson / Interview: Hurvin Anderson and Thelma Golden / Encodings / Portrait of the Artists / We Come With the Beautiful Things / Collected. / StudioSound / Harlem Postcards / 30 Seconds off an Inch / Wardell Milan: Drawings of Harlem 22 Sign of the Times 24 Collection Imagined 26 Facts + Figures 28 Elsewhere / Yinka Shonibare MBE / Project Room 1: Khalif Kelly: Electronicon / design for a living world / Stan Douglas: Klatsassin / Chakaia Booker: Cross Over Effects / Momentum 14: Rodney McMillian / Pathways to Unknown Worlds: Sun Ra, El Saturn & Chicago’s Afro-Futurist Underground, 1954–1968 34 Icon / Ernie Barnes 38 Feature / Islands of New York by Accra Shepp 44 Feature / Correspondence: Toomer & Johnson 46 Commissioned / Nina Chanel Abney 48 Feature / In the Studio 50 Icon / Robert Colescott 52 Feature / Expanding the Walls 54 Target Free Sundays at the Studio Museum 57 Education and Public Programs 61 New Product / Coloring Book 64 Development News / Spring Luncheon / Supporters 2008–09 / Membership 2009–10 72 Museum Store / More-in-Store: T-shirts Galore! Aishah Abdullah / Underdog / 2009 / Courtesy the artist 3 Studio 01/ Hurvin Anderson 02/ Hurvin Anderson Peter’s 1 Barbershop 1 What’s Up 2007 2006 Courtesy Government Courtesy Bridgitt Hurvin Anderson Arts Collection, London and Bruce Evans Peter's Series 2007–2009 July 16–October 25, 2009 The Studio Museum in Harlem is proud to present the shop was not only a place to get a haircut, but also a social first solo U.S. -

Sedrick Huckaby Was Born in 1975 in Fort Worth, Texas. He Earned a BFA at Boston University in 1997 and an MFA at Yale University in 1999

Philip Martin Gallery Sedrick Huckaby was born in 1975 in Fort Worth, Texas. He earned a BFA at Boston University in 1997 and an MFA at Yale University in 1999. Sedrick has earned many awards and honors for his art including a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2008 and a Joan Mitchell Grant in 2004. He is an associate professor of painting at the University of Texas at Arlington and his work is represented by Valley House Gallery in Dallas, Texas. As a kid, Sedrick loved reruns of the seventies TV show Good Times. We both did. We were both inspired by the artiste character — J.J. Walker — and especially Ernie Barnes who was the real painter behind the best paintings seen on that show. Ernie Barnes was famous as a painter and an athlete. He played professional football from 1959 to 1965. In high school, Sedrick was a competitive athlete too and fencing was his sport of choice. In my mind, this connects Sedrick to Caravaggio who was also good with a sword. Unlike Caravaggio and more like Ernie Barnes — Sedrick is levelheaded and loves people but I’ve always felt that I can see the swordsman in Sedrick’s paint handling. Sedrick is a devoted father of three and husband to Letitia Huckaby who is also a visual artist. They live in Fort Worth, Texas, not too far from the Highland Hills neighborhood where he grew up. His parents and extended family all live in Fort Worth too. Family and community are important to Sedrick. 2712 S. La Cienega Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90034 philipmartingallery.com (310) 559-0100 Philip Martin Gallery In early 2018 Sedrick spent time as artist in residence at a hospital in Philadelphia, PA where he made drawings of patients and doctors while listening to them tell their stories. -

(RCAF) Chicano/A Art Collective

INTRODUCTION Mapping the Chicano/a Art History of the Royal Chicano Air Force he Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF) Chicano/a art collective pro duced major works of art, poetry, prose, music, and performance in T the United States during the second half of the twentieth century and the first decades of the twenty-first. Merging the hegemonic signs, sym bols, and texts of two nations with particular but often fragmented knowl edge of their indigenous ancestries, members of the RCAF were among a generation of Chicano/a artists in the 1960s and 1970s who revolution ized traditional genres of art through fusions of content and form in ways that continue to influence artistic practices in the twenty-first century. Encompassing artists, students, military veterans, community and labor activists, professors, poets, and musicians (and many members who identi fied with more than one of these terms), the RCAF redefined the meaning of artistic production and artwork to account for their expansive reper toire, which was inseparable from the community-based orientation of the group. The RCAF emerged in Sacramento, California, in 1969 and became established between 1970 and 1972.1 The group's work ranged from poster making, muralism, poetry, music, and performance, to a breakfast program, community art classes, and political and labor activism. Subsequently, the RCAF anticipated areas of new genre art that rely on community engage ment and relational aesthetics, despite exclusions of Chicano/a artists from these categories of art in the United States (Bourriaud 2002). Because the RCAF pushed definitions of art to include modes of production beyond tra ditional definitions and Eurocentric values, women factored significantly in the collective's output, navigating and challenging the overarching patri archal cultural norms of the Chicano movement and its manifestations in the RCAF. -

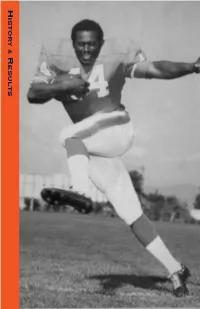

Special Art Exhibit Featuring Works of Ernie Barnes to Open June 19

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: June 12, 2014 Joe Horrigan at (330) 588-3627 Pete Fierle at (330) 588-3622 SPECIAL ART EXHIBIT FEATURING WORKS OF ERNIE BARNES TO OPEN JUNE 19 Renowned artist was former pro football player The “artistry” of football will be on display at the Pro Football Hall of Fame starting on Thursday, June 19. That is when a special exhibit “From Pads to Palette, Celebrating the Art of Ernie Barnes (1938-2009)” will open for a four-month stay at the museum. It will mark the first time that the Pro Football Hall of Fame has hosted an art exhibit by a former professional football player. Barnes, a 6-3, 247-pound offensive lineman was drafted by the Baltimore Colts in 1959. After being cut by the Colts, he joined the American Football League’s New York Titans in 1960. He then signed as a free agent with the San Diego Chargers where he played for two seasons (1961-62). Barnes ended his playing career as a member of the 1963-64 Denver Broncos. Although a gifted athlete, Barnes confessed that he had little interest in sports as a youngster. It wasn’t until he attended Hillside High School in Durham, N.C. and only after coaxing from the head coach did he decide to give football a try. His outstanding play earned him 26 athletic scholarship offers from colleges and universities. He settled on North Carolina College (now North Carolina Central University) where he distinguished himself as one of the top linemen in the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association.