A View of Unconcealed Alterities and Affirmations of Chicana Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 WS 560 Chicana Feminism Course Syllabus Class Time

WS 560 Chicana Feminism Course Syllabus Class time: MW 1:30-3:18 Phone: 247-7720 Classroom: ----- Email: [email protected] Instructor: Professor Guisela Latorre Office Hours: ------ Office: ------ Course Description This course will provide students with a general background on Chicana feminist thought. Chicana feminism has carved out a discursive space for Chicanas and other women of color, a space where they can articulate their experiences at the intersection of race, class, gender, sexuality, among other considerations. In the process, Chicana feminists have critically challenged Chicano nationalist discourse as well as European and North American feminism. This challenge has placed them in a unique albeit isolated position in relationship other established discourses about liberation and decolonization. Through this class, we will address the diversity in thinking and methodology that defines these discourses thus acknowledging the existence of a variety of feminisms that occur within Chicana intellectual thought. We will also explore the diversity of realms where this feminist thinking is applied: labor, education, cultural production (literature, art, performance, etc.), sexuality, spirituality, among others. Ultimately, we will arrive at the understanding that Chicana feminism is as much an intellectual and theoretical discourse as it is a strategy for survival and success for women of color in a highly stratified society. Each class will be composed of a lecture and discussion component. During the lecture I will cover some basic background information on Chicana feminism to provide students with the proper contextualization for the readings. After the lecture we will engage in a seminar-style discussion about the readings and their connections to the lecture material. -

806/317-0676 E-Mail: [email protected]

DR. CONSTANCE CORTEZ School of Art, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas 79409 (cell) 806/317-0676 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: 1995 Doctor of Philosophy (Art History), University of California, Los Angeles Dissertation: "Gaspar Antonio Chi and the Xiu Family Tree" •Major: Contact Period and Colonial Art of México •Minors: Chicano/a Art, Pre-Columbian Art of México, Classical Art •Areas of Specialization: Conquest Period cultures of the Americas & colonial and postcolonial discourse 1986 Master of Arts (Art History), The University of Texas at Austin Masters Thesis: "The Principal Bird Deity in Late Preclassic & Early Classic Maya Art" •Major: Pre-Columbian Art •Minor: Latin American Studies •Area of Specialization: Classic Maya Iconography and Epigraphy 1981 Bachelor of Arts (Art History), The University of Texas at Austin TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Sept.2003- Associate Professor, Texas Tech University (Tenure/Promotion to Associate, March 6, 2009) present Graduate courses: Themes of Contemporary Art [1985-2013]; Contemporary Theory; Methodology; Memory & Art; The Body in Contemporary Art. Undergraduate courses: Themes of Contemporary Art; Contemporary Chicana/o Art; 19th-20th century Mexican Art; Colonial Art of México; Survey II [Renaissance -Impression.]; Survey III [Post Impressionism - Contemporary]. Sept.1997- Assistant Professor, Santa Clara University May 2003 Tenure-track appointment. Undergraduate: Chicana/o Art; Modern Latin American Art; Colonial Art of Mexico & Perú; Pre-Columbian Art, Native North American Art; Survey of the Arts of Oceania, Africa, & the Americas. Sept.1996- Visiting Lecturer, University of California at Santa Cruz June 1997 Nine-month appointment. Undergraduate: Chicana/o Art; Colonial Art of México; Pre-Columbian Art, Native North American Art; Survey of the Arts of Oceania, Africa, & the Americas. -

(RCAF) Chicano/A Art Collective

INTRODUCTION Mapping the Chicano/a Art History of the Royal Chicano Air Force he Royal Chicano Air Force (RCAF) Chicano/a art collective pro duced major works of art, poetry, prose, music, and performance in T the United States during the second half of the twentieth century and the first decades of the twenty-first. Merging the hegemonic signs, sym bols, and texts of two nations with particular but often fragmented knowl edge of their indigenous ancestries, members of the RCAF were among a generation of Chicano/a artists in the 1960s and 1970s who revolution ized traditional genres of art through fusions of content and form in ways that continue to influence artistic practices in the twenty-first century. Encompassing artists, students, military veterans, community and labor activists, professors, poets, and musicians (and many members who identi fied with more than one of these terms), the RCAF redefined the meaning of artistic production and artwork to account for their expansive reper toire, which was inseparable from the community-based orientation of the group. The RCAF emerged in Sacramento, California, in 1969 and became established between 1970 and 1972.1 The group's work ranged from poster making, muralism, poetry, music, and performance, to a breakfast program, community art classes, and political and labor activism. Subsequently, the RCAF anticipated areas of new genre art that rely on community engage ment and relational aesthetics, despite exclusions of Chicano/a artists from these categories of art in the United States (Bourriaud 2002). Because the RCAF pushed definitions of art to include modes of production beyond tra ditional definitions and Eurocentric values, women factored significantly in the collective's output, navigating and challenging the overarching patri archal cultural norms of the Chicano movement and its manifestations in the RCAF. -

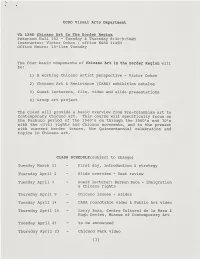

UCSD Visual Arts Department VA 128D Chicano Art

- UCSD Visual Arts Department VA 128D Chicano Art In The Border Region Peterson Hall 102 - Tuesday & Thursday 8:30-9:50AM Instructor: Victor Ochoa / office H&SS 1145D Office Hours: 10-11am Tuesday The four basic components of Chicano Art in the Border Region will be: 1) A working Chicano artist perspective - Victor Ochoa 2) Chicano Art & Resistance (CARA) exhibition catalog 3) Guest lecturers, film, video and slide presentations 4) Group art project The class will provide a basic overview from Pre-Colombian art to Contemporary Chicano art. This course will specifically focus on the Pachuco period of the 1940's on through the 1960's and 70's with the civil rights and Chicano movements, and to the present with current border issues, the Quincentennial celebration and topics in Chicana art. CLASS SCHEDULE(subject to change) Tuesday March 31 First day, introduction & strategy Thursday April 2 Slide overview - Text review Tuesday April 7 Guest lecturer: Herman Baca - immigration & Chicano rights Thursday April 9 - Chicano issues - slides Tuesday April 14 - CARA roundtable video & Public Art video Thursday April 16 - Larry Baza, Centro Cultural de la Raza & Hugh Davies, Museum of Contemporary Art Tuesday April 21 - to be announced Thursday April 23 - Chicano Park video [1] VA 128D(cont.) Saturday April 25 - Chicano Park Day - required field trip Tuesday April 28 - Issac Artenstein - "Mi Otro Yo" & video potpourri Thursday April 30 - Ireina Cervantes: personal work, Chicanas & Frida (Midterm due) Tuesday May 5 - David Avalos & BAW/TAF the -

Altar/Installations by Amalia Mesa-Bains in a Feminist Context

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-2-2019 Altar/Installations by Amalia Mesa-Bains in a Feminist Context Carmen del Valle Hermo CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/437 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Altar/Installations by Amalia Mesa-Bains in a Feminist Context by Carmen del Valle Hermo Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York May 6, 2019 Thesis Sponsor: April 15, 2019 Dr. Harper Montgomery Date Signature April 4, 2019 Dr. Cynthia Hahn Date Signature of Second Reader TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Illustrations………………………………………………………………………………..iii Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………..........1 Chapter 1: Chicanx Traditions, Refreshed and Refashioned: Creating and Naming the Altar/Installation………………………………………………………………………………....13 Chapter 2: Honoring a Woman, Honoring an Experience……………………………………….39 Chapter 3: Mesa-Bains, Between Feminisms……………………………………………………54 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….74 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..77 Illustrations………………………………………………………………………………………81 i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to begin by thanking Dr. Harper Montgomery for her insight, guidance, and support throughout my time at Hunter College, and especially in the preparation of this thesis. Her careful readings and revisions sharpened my arguments and sustained me during the editing process. I also thank Dr. Cynthia Hahn for her generosity in time and attention spent with this paper. -

Chicano and Chicana Art a CRITICAL ANTHOLOGY

Jennifer A. González, C. Ondine Chavoya, Chon Noriega, Chicano & Terezita Romo, editors and Chicana Art A CRITICAL ANTHOLOGY Chicano and Chicana Art A CRITICAL ANTHOLOGY jennifer a. gonzález, c. ondine chavoya, chon noriega, and terezita romo, editors Duke University Press · Durham and London · 2019 © 2019 DUKE UNIVERSITY PRESS All rights reserved. Printed in the United States isbn 9781478003403 (ebook) of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞. Designed by isbn 9781478001874 (hardcover : alk. paper) Courtney Leigh Baker. Typeset in Minion Pro and isbn 9781478003007 (pbk. : alk. paper) Myriad Pro by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Subjects: lcsh: Mexican American art. | Mexican American artists. | Art— Political aspects— United States. | Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Art and society. Names: González, Jennifer A., editor. | Classification: lcc n6538.m4 (ebook) | Chavoya, C. Ondine, editor. | lcc n6538.m4 c44 2019 (print) | Noriega, Chon A., [date] editor. | Romo, Terecita, editor. ddc 704.03/6872073— dc23 Title: Chicano and Chicana art : a critical anthology / lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2018026167 Jennifer A. González, C. Ondine Chavoya, Chon Noriega, Terezita Romo, editors. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Frontispiece: Ester Hernández, Libertad, 1976. Includes bibliographical references and index. Etching. Image courtesy of the artist. Identifiers: lccn 2018026167 (print) Cover art: Richard A. Lou, Border Door, 1988. lccn 2018029607 (ebook) Photo by James Elliot. Courtesy of the artist. PART I. DEFINITIONS AND DEBATES Introduction · 13 chon noriega 1. Looking for Alternatives: Notes on Chicano Art, 1960–1990 · 19 philip brookman 2. Con Safo (C/S) Artists: A Contingency Factor · 30 mel casas Contents 3. -

Documents of 20Th-Century Latin American and Latino Art a DIGITAL ARCHIVE and PUBLICATIONS PROJECT at the MUSEUM of FINE ARTS, HOUSTON

International Center for the Arts of the Americas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Documents of 20th-century Latin American and Latino Art A DIGITAL ARCHIVE AND PUBLICATIONS PROJECT AT THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON ICAA Record ID: 803291 Access Date: 2017-12-06 Bibliographic Citation: Goldman, Shifra M. "Introduction" In Chicano Voices and Visions: A National Exhibit of Women Artists, Exh. cat.,Venice, CA: Social & Public Art Resource Center (SPARC), 1983 WARNING: This document is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Reproduction Synopsis: or downloading for personal Shifra M. Goldman’s essay provides a brief history of the Chicano Movement and also names use or inclusion of any portion some of the early Mexican American women’s political groups, professional associations, and art of this document in another work intended for commercial groups. She discusses the overall failure of the Chicano Movement in order to challenge gender purpose will require permission inequality and the sexist stereotypes inflicted upon Chicanas. While acknowledging the influence from the copyright owner(s). of feminism on Chicanas, she says that the racism and classism within white feminism at times ADVERTENCIA: Este docu- polarized Euro-American and Third World feminists. Goldman explains the difficulties that mento está protegido bajo la ley de derechos de autor. Se women artists faced in participating in the early phase of the Chicano art movement that was reservan todos los derechos. dominated by public art forms, comparing this to the surge of Chicana artists who appeared in Su reproducción o descarga the late-1970s when Chicano art shifted to gallery, museum, and college exhibition venues. -

The Visual Rhetoric of Pre-Columbian Imagery in Chicano Murals

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research 2011 Reclaiming Aztlán: The iV sual Rhetoric of Pre- Columbian Imagery in Chicano Murals Kelsey Mahler [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Contemporary Art Commons Recommended Citation Mahler, Kelsey, "Reclaiming Aztlán: The iV sual Rhetoric of Pre-Columbian Imagery in Chicano Murals" (2011). Summer Research. Paper 119. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/119 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reclaiming Aztlán: The Visual Rhetoric of Pre-Columbian Imagery in Chicano Murals As the Chicano movement took shape in the 1960s, Chicano artists quickly began to articulate the attitudes and goals of the movement in the form of murals that decorated businesses, freeway underpasses, and low-income housing developments. It did not take long for a distinct aesthetic to emerge. Many of the same visual symbols repeatedly appear in these murals, especially those produced during the first two decades of the movement. These included images of historical Mexican or Chicano figures such as Cesar Chavez, Pancho Villa, and Dolores Huerta, cultural icons like the Virgin of Guadalupe, and emblems of political consciousness like the flag of the United Farm Workers. But one of the most important visual themes that emerged was the use of pre-Columbian imagery, which could include images of Aztec or Mayan warriors, gods like Coatlicue or Quetzacoatl, the Aztec calendar stone, depictions of ancient Mesoamerican pyramid architecture, or the Olmec head sculptures found at San Lorenzo and La Venta. -

A Chicana Experience

Sincronía ISSN: 1562-384X [email protected] Universidad de Guadalajara México Objects and narratives from Mexican roots artists: a Chicana experience Castellano González, Cristina Isabel Objects and narratives from Mexican roots artists: a Chicana experience Sincronía, no. 72, 2017 Universidad de Guadalajara, México Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=513852524037 PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Miscelanea Objects and narratives from Mexican roots artists: a Chicana experience Objetos y narrativas de artistas con raíces mexicanas: una experiencia chicana Cristina Isabel Castellano González [email protected] Universidad de Guadalajara, México Abstract: e purpose of this brief article is to discuss the context and the political tensions that existed when women artists with Mexican roots invented a political Chicano art engagé at Los Angeles. We study the creations of Judithe Hernandez and Patssi Valdez, two artists with Mexican roots, who have challenged the codes of the dominant, patriarchal, and white art world of the United States since 1970. As artists, they become a symbol of professional success for women in the arts. Sincronía, no. 72, 2017 ey developed personal art expressions and leg their own art vision of America, Universidad de Guadalajara, México women, and community. ey used streets, walls and displayed public performances. Nevertheless, the originality of this text relies on the analyses of some art pieces from Received: 11 December 2016 their contemporary period. e text emphasizes the technical transformation of both Revised: 13 March 2017 Accepted: 25 April 2017 legendary artists who gave up performance and mural art to develop personal and critical propositions about women condition (myths, femicide) and borders. -

The Chicano Art Movement Curated by Chon A

Mapping Another L.A.: The Chicano Art Movement Curated by Chon A. Noriega, Terezita Romo, and Pilar Tompkins Rivas. Shown at the Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles October 16, 2011- February 26, 2012 Robb Hernandez A mural façade entitled The Birth of Our Art (1971), designed by Don Juan otherwise known as Johnny D. Gonzalez, opened Mapping Another L.A.: The Chicano Art Movement, on view at the Fowler Museum at UCLA from October 2011 until February 2012. For the first time since 1981, the wood panels that once covered the exterior walls of the Goez Art Gallery in East Los Angeles were reconstructed for public viewing after being recovered from the storage unit of the designer’s brother and Goez co-founder, Joe Gonzalez.1 The mural’s appearance in the immediate foray of the gallery space was a bold visual and spatial statement that rearticulated the interrelationship between Chicana/o image and place – an indexing of barrio aesthetics and vernacular architecture in the Goez gallery front, as well as the commemorative style and language of the modern frieze it composes. A 33-foot long towering landmark that honors Chicana/o artists’ prolific art and literary production at the precipice of the Chicano civil rights movement in the late 1960s, this mural memorialized culturally-affirming narratives as it beckoned passage: beyond a Spanish-colonial suit of armor and a Quetzalcoatl head standing guard before the Goez façade in the main gallery stood the artifacts of “another L.A.” For the museum visitor, these figures, silkscreens, newsprint, ephemera, and maps visually encapsulated the regenerative sentiment of the mural’s title and thus gave “birth [to] our art.” For this, Mapping Another L.A.’s provocative mural installation in the Fowler museum challenged the dominant vision of contemporary art in California by revealing a counter image of the city, one that vacillates against and between violent racially-stratified realities and proliferating cultural visibility. -

Barbara Carrasco Interviewed by Karen Mary Davalos on August 30, September 11 and 21, and October 10, 2007

CSRC ORAL HISTORIES SERIES NO. 3, NOVEMBER 2013 BARBARA CARRASCO INTERVIEWED BY KAREN MARY DAVALOS ON AUGUST 30, SEPTEMBER 11 AND 21, AND OCTOBER 10, 2007 Artist and muralist Barbara Carrasco lives and works in Los Angeles. She received her BFA from UCLA and her MFA from California Institute of the Arts. Her work has been exhibited throughout the United States, Europe, and Latin America. Carrasco has taught at UC Riverside, UC Santa Barbara, and Loyola Marymount University and is the recipient of a number of fellowships and grants. Her papers are held in the Department of Special Collections at Stanford University and the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Karen Mary Davalos is chair and professor of Chicana/o studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Her research interests encompass representational practices, including art exhibition and collection; vernacular performance; spirituality; feminist scholarship and epistemologies; and oral history. Among her publications are Yolanda M. López (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2008); “The Mexican Museum of San Francisco: A Brief History with an Interpretive Analysis,” in The Mexican Museum of San Francisco Papers, 1971–2006 (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2010); and Exhibiting Mestizaje: Mexican (American) Museums in the Diaspora (University of New Mexico Press, 2001). This interview was conducted as part of the L.A. Xicano project. Preferred citation: Barbara Carrasco, interview with Karen Mary Davalos, August 30, September 11 and 21, and October 10, 2007, Los Angeles, California. CSRC Oral Histories Series, no. 3. Los Angeles: UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2013. -

1 Chicana and Chicano

Chicana and Chicano Art: A History of an American Art Movement, 1965 to the Present Professor Holly Barnet-Sanchez University of New Mexico T/Th, 12:30-1:45 Course Description: The Chicano Art Movement began in the mid-1960s in support of the Chicano Civil Rights Movement (el movimiento). For the next two decades Chicana and Chicano artists throughout the nation created artworks in all media that addressed, celebrated, and critiqued the rich cultural heritage of the Mexican American people, the political and civil struggles of their communities, and their commitment to international contemporary cultural and political innovation. If the Chicano Art Movement ended in 1985 or 1990 (as is debated) what has been happening in the past 20 + years? This semester we will explore the history of Chicana/o artistic production from its beginnings in political struggle, aesthetic exploration, and community building, to recent developments in the art world and in digital/new media, among other areas of engagement. We will examine the critical role of collective art forms and practices and the relationship to other Chicana/o arts (teatro, cinema, music, literature). In addition, we will address the historical and ongoing debates within Chicana/o communities about the purposes and limits of art, how it can affect understanding and effect meaning, how it can or cannot change lives, social structures, and systems of control and knowledge. Within a structure that organizes the material both chronologically and thematically, we will study the work of individual artists, grupos (artists’ groups or collectives), and several of the key centros (cultural centers) throughout the United States in order to arrive at a hopefully extensive, if not exhaustive, overview of the myriad forms, transformations of traditional practices, iconographical and formal innovations, practices, issues, and debates that inform this movement.