Cultural Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

University Microiilms, a XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

71-18,075 RINEHART, John McLain, 1937- IVES' COMPOSITIONAL IDIOMS: AN INVESTIGATION OF SELECTED SHORT COMPOSITIONS AS MICROCOSMS' OF HIS MUSICAL LANGUAGE. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1970 Music University Microiilms, A XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan © Copyright by John McLain Rinehart 1971 tutc nTccrSTATmil HAS fiEEM MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED IVES' COMPOSITIONAL IDIOMS: AM IMVESTIOAT10M OF SELECTED SHORT COMPOSITIONS AS MICROCOSMS OF HIS MUSICAL LANGUAGE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy 3n the Graduate School of The Ohio State University £ JohnfRinehart, A.B., M«M. # # * -k * * # The Ohio State University 1970 Approved by .s* ' ( y ^MrrXfOor School of Music ACm.WTji.D0F,:4ENTS Grateful acknov/ledgement is made to the library of the Yale School of Music for permission to make use of manuscript materials from the Ives Collection, I further vrish to express gratitude to Professor IJoman Phelps, whose wise counsel and keen awareness of music theory have guided me in thi3 project. Finally, I wish to acknowledge my wife, Jennifer, without whose patience and expertise this project would never have come to fruition. it VITA March 17, 1937 • ••••• Dorn - Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 1959 • • • • • .......... A#B#, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 1960-1963 . * ........... Instructor, Cleveland Institute of Music, Cleveland, Ohio 1 9 6 1 ................ • • • M.M., Cleveland Institute of ITu3ic, Cleveland, Ohio 1963-1970 .......... • • • Associate Professor of Music, Heidelberg College, Tiffin, Ohio PUBLICATIONS Credo, for unaccompanied chorus# New York: Plymouth Music Company, 1969. FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: Theory and Composition Studies in Theory# Professor Norman Phelps Studies in Musicology# Professors Richard Hoppin and Lee Rigsby ill TAPLE OF CC NTEKTS A C KI JO WLE DGEME MT S ............................................... -

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad An extract from the Irish Sport Horse Studbook Stallion Book The Irish Sport Horse Studbook is maintained by Horse Sport Ireland and the Northern Ireland Horse Board Horse Sport Ireland First Floor, Beech House, Millennium Park, Osberstown, Naas, Co. Kildare, Ireland Telephone: 045 850800. Int: +353 45 850800 Fax: 045 850850. Int: +353 45 850850 Email: [email protected] Website: www.horsesportireland.ie Northern Ireland Horse Board Office Suite, Meadows Equestrian Centre Embankment Road, Lurgan Co. Armagh, BT66 6NE, Northern Ireland Telephone: 028 38 343355 Fax: 028 38 325332 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nihorseboard.org Copyright © Horse Sport Ireland 2015 HIGH PERFORMANCE STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD INDEX OF APPROVED STALLIONS BY BREED HIGH PERFORMANCE RECOGNISED FOREIGN BREED STALLIONS & STALLIONS STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD & ACANTUS GK....................................4 APPROVED THROUGH AI ACTION BREAKER.............................4 BALLOON [GBR] .............................10 KROONGRAAF............................... 62 AIR JORDAN Z.................................. 5 CANABIS Z......................................18 LAGON DE L'ABBAYE..................... 63 ALLIGATOR FONTAINE..................... 6 CANTURO.......................................19 LANDJUWEEL ST. HUBERT ............ 64 AMARETTO DARCO ......................... 7 CASALL LA SILLA.............................22 LARINO.......................................... 66 -

2018 Fall Olympics Events and Rules: Game 1: Flip Cup- 5 Games

2018 Fall Olympics Events and Rules: Game 1: Flip Cup- 5 games • Teams of 4 line up across the table from each other. • Each player has approximately half a cup of beer. The amount should be the same for each player. • The goal is for each player to chug their drink and then flip their empty solo cup using the edge of the table so that it lands upside down. • Once a cup is successfully flipped, the next player will than need to drink their beer and then flip the cup. • This is a relay race so the first team to have all their beer finished and their cups flipped wins. • Winning of team receives 1 point for each of the 5 games. Winning team remains at their table, losing team rotates to next table over. Game 2: Dizzy Bat – 2 Games • 4 players on each team • There will be 2 players on each side of a 20 yard “field” • Side A: Person 1 will do 5 spins with bat, then chug their beer, then run to side B with bat in hand • Person 1 from side A will hand bat to person 2 on Side B who then does the same…. 5 spins w/ bat, chug, then run to Side A to person 3…. Repeat until person 4 crosses line at sign A. • First team to get person 4 across side A wins. • Teams will be lined up 10 yds apart from each other (no tripping, adjusting the cones or interfering with the competing team or you will be given a 10 second penalty each time). -

Littleton Bible Chapel Position Paper Covering and Uncovering of The

Littleton Bible Chapel Position Paper Covering and Uncovering of the Head during Prayer and Ministry of the Word 1 Corinthians 11:2-16 It has been the practice of LBC for the past forty-five years to ask women to cover their heads when they pray and teach publicly, and for men to uncover their heads when they pray and teach in a public setting. This practice is not an empty tradition of our church but a direct injunction of the Scriptures. We have prepared the following paper on 1 Corinthians 11:2-16, for you to consider the accuracy and the truthfulness of our practice. It is our desire to encourage believers to take this passage seriously and to consistently practice the teaching therein. This has been a long neglected passage, and today is completely unacceptable in our feminist environment. We understand the offense of this teaching. But since we take the passage at face value and not as cultural, we have no choice but to practice its teaching. Our desire as elders is to make people aware of what the Bible teaches about this distinctive Christian practice and to encourage both men and women to practice this teaching. If however, people disagree with our interpretation, we do not force this practice on anyone. We respect the liberty of the conscience of all our fellow believers. 1 1 Corinthians 11:2-16 Headship and Subordination Symbolized by Covering and Uncovering of the Head The letter of 1 Corinthians deals with many practical local church issues and problems, ones that affect all churches in all ages. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2013 a 19

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe A Monografien und Periodika des Verlagsbuchhandels Wöchentliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2013 A 19 Stand: 08. Mai 2013 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2013 ISSN 1869-3946 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheA19_2013-3 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. In Reihe A werden Medienwerke, die im Verlagsbuch- chende Menüfunktion möglich. Die Bände eines mehrbän- handel erscheinen, angezeigt. Auch außerhalb des Ver- digen Werkes werden, sofern sie eine eigene Sachgrup- lagsbuchhandels erschienene Medienwerke werden an- pe haben, innerhalb der eigenen Sachgruppe aufgeführt, gezeigt, wenn sie von gewerbsmäßigen Verlagen vertrie- ansonsten -

“The Addams Family” Costume Plot

“THE ADDAMS FAMILY” COSTUME PLOT GOMEZ Black pinstriped suit, tie, suspenders and shirt Dinner: shawl collar or smoking jacket and bow tie Bull fighter cape Beret White button down shirt MORTICIA Long tight fitting black gown with breakaway skirt Half apron Black cape Floppy hat WEDNESDAY Black knee length dress with white collar and cuffs Yellow knee length dress with white collar and cuffs Black jacket or coat Short bridal dress and veil PUGSLEY Black and white striped tee shirt, black shorts Black and white striped pajamas Boy Scout scarf GRANDMA Loose dress, non-matching poncho or cardigan, fingerless gloves Nurse cap, candy striper apron, sleeve protectors LURCH Black suit, black bowtie, white button down shirt UNCLE FESTER Long black coat with fur trim, black pants, belly pad Black and white striped bathing suit. Goggles, aviator cap and scarf LUCAS Blazer, pants shirt and tie Page 1 of 2 “THE ADDAMS FAMILY” COSTUME PLOT MAL BEINEKE Three piece suit, tie, and white button down shirt Overcoat and hat Gomez style pajamas with spider on the back ALICE BEINEKE Yellow day dress, hat and purse Overcoat Morticia style pajamas GRIM REAPER Black hooded robe, belt Extra-long or two person grey fleece robe with hood and black out mask BATHING BEAUTIES Old fashion bathing attire STARS Black wraps skirt, black poncho and star headpiece ANCESTORS Caveman – tunic with layered fur pieces, fur caplet and rope belt Cavewoman – tunic with layered fur pieces, fur caplet and rope belt Conquistador – Cuirass, shirt with puffed sleeves, pants with puff -

Judicial System in India During Mughal Period with Special Reference to Persian Sources

Judicial System in India during Mughal Period with Special Reference to Persian Sources (Nezam-e-dadgahi-e-Hend der ahd-e-Gorkanian bewizha-e manabe-e farsi) For the Award ofthe Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submitted by Md. Sadique Hussain Under the Supervision of Dr. Akhlaque Ahmad Ansari Center Qf Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi -110067. 2009 Center of Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi -110067. Declaration Dated: 24th August, 2009 I declare that the work done in this thesis entitled "Judicial System in India during Mughal Period with special reference to Persian sources", for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy, submitted by me is an original research work and has not been previously submitted for any other university\Institution. Md.Sadique Hussain (Name of the Scholar) Dr.Akhlaque Ahmad Ansari (Supervisor) ~1 C"" ~... ". ~- : u- ...... ~· c "" ~·~·.:. Profess/~ar Mahdi 4 r:< ... ~::.. •• ~ ~ ~ :·f3{"~ (Chairperson) L~.·.~ . '" · \..:'lL•::;r,;:l'/ [' ft. ~ :;r ':1 ' . ; • " - .-.J / ~ ·. ; • : f • • ~-: I .:~ • ,. '· Attributed To My Parents INDEX Acknowledgment Introduction 1-7 Chapter-I 8-60 Chapter-2 61-88 Chapter-3 89-131 Chapter-4 132-157 Chapter-S 158-167 Chapter-6 168-267 Chapter-? 268-284 Chapter-& 285-287 Chapter-9 288-304 Chapter-10 305-308 Conclusion 309-314 Bibliography 315-320 Appendix 321-332 Acknowledgement At first I would like to praise God Almighty for making the tough situations and conditions easy and favorable to me and thus enabling me to write and complete my Ph.D Thesis work. -

Gesungene Aufklärung

Gesungene Aufklärung Untersuchungen zu nordwestdeutschen Gesangbuchreformen im späten 18. Jahrhundert Von der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg – Fachbereich IV Human- und Gesellschaftswissenschaften – zur Erlangung des Grades einer Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Dissertation von Barbara Stroeve geboren am 4. Oktober 1971 in Walsrode Referent: Prof. Dr. Ernst Hinrichs Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Peter Schleuning Tag der Disputation: 15.12.2005 Vorwort Der Anstoß zu diesem Thema ging von meiner Arbeit zum Ersten Staatsexamen aus, in der ich mich mit dem Oldenburgischen Gesangbuch während der Epoche der Auf- klärung beschäftigt habe. Professor Dr. Ernst Hinrichs hat mich ermuntert, meinen Forschungsansatz in einer Dissertation zu vertiefen. Mit großer Aufmerksamkeit und Sachkenntnis sowie konstruktiv-kritischen Anregungen betreute Ernst Hinrichs meine Promotion. Ihm gilt mein besonderer Dank. Ich danke Prof. Dr. Peter Schleuning für die Bereitschaft, mein Vorhaben zu un- terstützen und deren musiktheoretische und musikhistorische Anteile mit großer Sorgfalt zu prüfen. Mein herzlicher Dank gilt Prof. Dr. Hermann Kurzke, der meine Arbeit geduldig und mit steter Bereitschaft zum Gespräch gefördert hat. Manche Hilfe erfuhr ich durch Dr. Peter Albrecht, in Form von wertvollen Hinweisen und kritischen Denkanstößen. Während der Beschäftigung mit den Gesangbüchern der Aufklärung waren zahlreiche Gespräche mit den Stipendiaten des Graduiertenkollegs „Geistliches Lied und Kirchenlied interdisziplinär“ unschätzbar wichtig. Stellvertretend für einen inten- siven, inhaltlichen Austausch seien Dr. Andrea Neuhaus und Dr. Konstanze Grutschnig-Kieser genannt. Dem Evangelischen Studienwerk Villigst und der Deutschen Forschungsge- meinschaft danke ich für ihre finanzielle Unterstützung und Förderung während des Entstehungszeitraums dieser Arbeit. Ich widme diese Arbeit meinen Eltern, die dieses Vorhaben über Jahre bereit- willig unterstützt haben. -

Material Culture, Theoretical Culture, and Delocalization

PETER GALISON Material Culture, Theoretical Culture, and Delocalization Collection, laboratory, and theater – all face the unavoidable problem of moving the specific, tangible reality of a highly refined local circum- stance into a wider domain, if not of the universal, at least out of the here and now. In the study of science, simply recognizing the inevitably local origins of science has been an enormous accomplishment, perhaps the signal achievement of science studies over the past twenty years. But we then need to understand, again in specific terms, how this lo- cally-produced knowledge moves, how – without invoking an other- wise unexplained process of ‘generalization’ – scientific work is de- localized. My work over the last years (e.g. Image and Logic)1 has aimed at this goal, folding the local back on the local, so to speak, by asking how the local cultures of science link up through the piecewise coordination of bits of languages, objects, procedures. I have in mind much more austere and less grand ideas than the ‘translation,’ ‘trans- mission,’ or ‘diffusion’ of pre-existing meanings. Instead, my focus is on the way bare-bone trading may occur between different subcultures of science, or between subcultures of science and bits of the wider world in which they are fundamentally embedded. In this picture, nei- ther language nor the world of things changes all of a piece, and talk of world-changing Gestalt shifts give way to the particular building-up of scientific jargons, pidgins, and creoles. These trading languages be- come important as do shared bits of apparatus or fragments of theoreti- cal manipulation. -

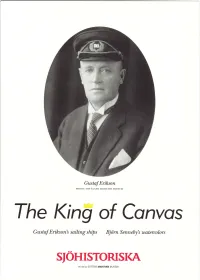

The Ki Ng of Conyos

The Ki ng of Conyos Gustaf Erikson's sai,ling shi,ps Bjtirn Senneby's watercolors sIoHrsToRrsKA en del av STATENS MARITIMA MUSEER ri#{ffi' r+f,**&:;]!$@$j! jr:+{ff 1*.; ff. Pamir Watercolor fu Bji;rn Senneby. GUSTAF ERIKSON The ship's owner, Gustaf Erikson, was born on Europe. The shipping company w:ls at its largest z4 October, r87z in Lemland, in southern Åland. in rg35, when Gustav was 58 years old. At the Both his father and grandfather had worked at time, the company had z9 vessels r5 of which sea. Gustafsson started his life at sea as a tG'year- were large sailing ships without alternative means old, when he served as a cabin boy on the bark of propulsion. GustafAdolf Mauritz Erikson died Neptun over the summer. When he reached r3, on August Lbn, rg47 in Mariehamn. he worked as a cook on the same vessel. He Gustaf Erikson was also part owner of advanced through the ranks and in r89r, at rg several steamers and motor vessels, but it was as years old, was the master's assistant on the barque the owner of the great sailing ships that he was Southern Bellc.In rgoo he took his captain's exlm best known. Four of his large sailing vessels, all and betr,veen 19o6 and r9r3 he was an executive four-masted steel barques, are preserved to this officer on different oceangoing voyages. day: Moshulu,whichwon the lastgrain race tggg, Over the years he had bought shares in is now a restaurant in Philadelphia, USA. -

Qt13j1570s.Pdf

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Early enlightenment in Istanbul Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/13j1570s Author Küc¿ük, Bekir Harun Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Early Enlightenment in Istanbul A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History and Science Studies by Bekir Harun Küçük Committee in charge: Professor Robert S. Westman, Chair Professor Frank P. Biess Professor Craig Callender Professor Luce Giard Professor Hasan Kayalı Professor John A. Marino 2012 Copyright Bekir Harun Küçük, 2012 All rights reserved. The dissertation of Bekir Harun Küçük is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii DEDICATION To Merve iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Dedication . iv Table of Contents . v List of Figures . vi List of Tables . vii Acknowledgements . viii Vita and Publications . xi Abstract of the Dissertation . xiii Chapter 1 Early Enlightenment in Istanbul . 1 Chapter 2 The Ahmedian Regime . 42 Chapter 3 Ottoman Theology in the Early Eighteenth Century . 77 Chapter 4 Natural Philosophy and Expertise: Convert Physicians and the Conversion of Ottoman Medicine . 104 Chapter 5 Contemplation and Virtue: Greek Aristotelianism at the Ottoman Court . 127 Chapter 6 The End of Aristotelianism: Upright Experience and the Printing Press . 160 Chapter 7 L’Homme Machine . 201 Bibliography . 204 v LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: The title page of Cottunius’s Commentarii.