Literature, Emotions, and Pre- Modern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Apish Art': Taste in Early Modern England

‘THE APISH ART’: TASTE IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND ELIZABETH LOUISE SWANN PHD THESIS UNIVERSITY OF YORK ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE JULY 2013 Abstract The recent burgeoning of sensory history has produced much valuable work. The sense of taste, however, remains neglected. Focusing on the early modern period, my thesis remedies this deficit. I propose that the eighteenth-century association of ‘taste’ with aesthetics constitutes a restriction, not an expansion, of its scope. Previously, taste’s epistemological jurisdiction was much wider: the word was frequently used to designate trial and testing, experiential knowledge, and mental judgement. Addressing sources ranging across manuscript commonplace books, drama, anatomical textbooks, devotional poetry, and ecclesiastical polemic, I interrogate the relation between taste as a mode of knowing, and contemporary experiences of the physical sense, arguing that the two are inextricable in this period. I focus in particular on four main areas of enquiry: early uses of ‘taste’ as a term for literary discernment; taste’s utility in the production of natural philosophical data and its rhetorical efficacy in the valorisation of experimental methodologies; taste’s role in the experience and articulation of religious faith; and a pervasive contemporary association between sweetness and erotic experience. Poised between acclaim and infamy, the sacred and the profane, taste in the seventeenth century is, as a contemporary iconographical print representing ‘Gustus’ expresses it, an ‘Apish Art’. My thesis illuminates the pivotal role which this ambivalent sense played in the articulation and negotiation of early modern obsessions including the nature and value of empirical knowledge, the attainment of grace, and the moral status of erotic pleasure, attesting in the process to a very real contiguity between different ways of knowing – experimental, empirical, textual, and rational – in the period. -

Religious Forms and Institutions in Piers Plowman

This essay appeared in The Cambridge Companion to Piers Plowman, edited by Andrew Cole and Andy Galloway (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 97-116 Religious Forms and Institutions in Piers Plowman James Simpson KEY WORDS: William Langland, Piers Plowman, selfhood and institutions; late medieval religious institutions ABSTRACT Which comes first: institutions or selves? Liberal democracies operate as if selves preceded institutions. By and large, pre-Reformation culture places the institution before the self. The self, and particularly the conscience as the source of deepest ethical and spiritual counsel, is intimately shaped, by the institution of the Church. This shaping is both ethical and spiritual; by no means least, it ensures the soul’s salvation, though administering the sacraments especially of baptism, penance, and the Eucharist. The conscience is not a lonely entity in such an institutional culture. It is, rather, the portable voice of accumulated, communal history and wisdom: it is, as the word itself suggests, a ‘con-scientia’, a ‘knowing with’. These tensions generate the extraordinary and conflicted account of self and institution in Langland’s Piers Plowman. 1 Religious Forms and Institutions in Piers Plowman Which comes first: institutions or selves? Liberal democracies operate as if selves preceded institutions, since electors choose their institutional representatives, who themselves vote to shape institutions. Liberal ideology, indeed, traces its genealogy back to heroic moments of the lonely, fully-formed conscience standing up against the might of institutions; those heroes (Luther is the most obvious example) are lionized precisely because they are said to have established the grounds of choice: every individual will be able to choose, in freedom, his or her institutional affiliation for him or herself. -

THE EARLY MODERN BOOK AS SPECTACLE by PAULINE

THROUGH A GLASS DARKLY: THE EARLY MODERN BOOK AS SPECTACLE by PAULINE E. REID (Under the Direction of Sujata Iyengar) ABSTRACT This dissertation approaches the print book as an epistemologically troubled new media in early modern English culture. I look at the visual interface of emblem books, almanacs, book maps, rhetorical tracts, and commonplace books as a lens for both phenomenological and political crises in the era. At the same historical moment that print expanded as a technology, competing concepts of sight took on a new cultural prominence. Vision became both a political tool and a religious controversy. The relationship between sight and perception in prominent classical sources had already been troubled: a projective model of vision, derived from Plato and Democritus, privileged interior, subjective vision, whereas the receptive model of Aristotle characterized sight as a sensory perception of external objects. The empirical model that assumes a less troubled relationship between sight and perception slowly advanced, while popular literature of the era portrayed vision as potentially deceptive, even diabolical. I argue that early print books actively respond to these visual controversies in their layout and design. Further, the act of interpreting different images, texts, and paratexts lends itself to an oscillation of the reading eye between the book’s different, partial components and its more holistic message. This tension between part and whole appears throughout these books’ technical apparatus and ideological concerns; this tension also echoes the conflict between unity and fragmentation in early modern English national politics. Sight, politics, and the reading process interact to construct the early English print book’s formal aspects and to pull these formal components apart in a process of biblioclasm. -

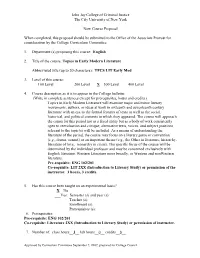

LIT 372 Topics in Early Modern Literature

John Jay College of Criminal Justice The City University of New York New Course Proposal When completed, this proposal should be submitted to the Office of the Associate Provost for consideration by the College Curriculum Committee. 1. Department (s) proposing this course: English 2. Title of the course: Topics in Early Modern Literature Abbreviated title (up to 20 characters): TPCS LIT Early Mod 3. Level of this course: ___100 Level ____200 Level ___X__300 Level ____400 Level 4. Course description as it is to appear in the College bulletin: (Write in complete sentences except for prerequisites, hours and credits.) Topics in Early Modern Literature will examine major and minor literary movements, authors, or ideas at work in sixteenth and seventeenth century literature with an eye to the formal features of texts as well as the social, historical, and political contexts in which they appeared. The course will approach the canon for this period not as a fixed entity but as a body of work consistently open to reevaluation and critique; alternative texts, voices, and subject positions relevant to the topic(s) will be included. As a means of understanding the literature of the period, the course may focus on a literary genre or convention (e.g., drama, sonnet) or an important theme (e.g., the Other in literature, hierarchy, literature of love, monarchy in crisis). The specific focus of the course will be determined by the individual professor and may be concerned exclusively with English literature, Western Literature more broadly, or Western and nonWestern literature. Pre-requisite: ENG 102/201 Co-requisite: LIT 2XX (Introduction to Literary Study) or permission of the instructor. -

On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’Ichi)

On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’ichi) On the Study of Early Modern“ Elegant” Literature Suzuki Ken’ichi On 21 November 2014, I was fortunate enough to be given the opportunity to talk about my past research at the Research Center for Science Systems affiliated to the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. There follows a summary of my talk. (1)Elucidating the distinctive qualities of early-Edo 江戸 literature, with a special focus on “elegant” or “refined”(ga 雅)literature, such as the poetry circles of the emperor Go-Mizunoo 後水尾 and the literary activities of Hayashi Razan 林羅山 . The importance of the study of “elegant” literature ・Up until around the 1970s interest in the field of early modern, or Edo-period, literature concentrated on figures such as Bashō 芭蕉,Saikaku 西鶴,and Chikamatsu 近松 of the Genroku 元禄 era(1688─1704)and Sanba 三馬,Ikku 一 九,and Bakin 馬 琴 of the Kasei 化 政 era(1804─30), and the literature of this period tended to be considered to possess a high degree of “common” or “popular”(zoku 俗)appeal. This was linked to a tendency, influenced by postwar views of history and literature, to hold in high regard that aspect of early modern literature in which “commoners resisted the oppression of the feudal 39 On the Study of Early Modern “Elegant” Literature(Suzuki Ken’ichi) system.” But when considered in light of the actual situation at the time, there can be no doubt that ga literature in the form of poetry written in both Japanese (waka 和歌)and Chinese(kanshi 漢詩), with its strong traditions, was a major presence in terms of both its authority and the formation of literary currents of thought. -

Piers Plowman

THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO PIERS PLOWMAN EDITED BY ANDREW COLE AND ANDREW GALLOWAY Downloaded from Cambridge Companions Online by IP 130.132.173.181 on Fri Nov 21 02:24:17 GMT 2014. http://universitypublishingonline.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CCO9780511920691 Cambridge Companions Online © Cambridge University Press, 2014 University Printing House, Cambridge cb2 8bs,UnitedKingdom Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107401587 ⃝c Cambridge University Press 2014 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2014 Printed in the United Kingdom by Clays, St Ives plc AcataloguerecordforthispublicationisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data The Cambridge Companion to Piers Plowman / edited by Andrew Cole and Andrew Galloway. pages cm. – (Cambridge Companions to Literature) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-1-107-00918-9 (hardback) 1.Langland,William,1330?–1400?PiersPlowman. I.Cole,Andrew,1968– editor of compilation. II. Galloway, Andrew, editor of compilation. pr2015.c27 2013 821′.1 – dc23 2013039685 isbn 978-1-107-00918-9 Hardback isbn 978-1-107-40158-7 Paperback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. -

The Forest and Social Change in Early Modern English Literature, 1590–1700

The Forest and Social Change in Early Modern English Literature, 1590–1700 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Elizabeth Marie Weixel IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. John Watkins, Adviser April 2009 © Elizabeth Marie Weixel, 2009 i Acknowledgements In such a wood of words … …there be more ways to the wood than one. —John Milton, A Brief History of Moscovia (1674) —English proverb Many people have made this project possible and fruitful. My greatest thanks go to my adviser, John Watkins, whose expansive expertise, professional generosity, and evident faith that I would figure things out have made my graduate studies rewarding. I count myself fortunate to have studied under his tutelage. I also wish to thank the members of my committee: Rebecca Krug for straightforward and honest critique that made my thinking and writing stronger, Shirley Nelson Garner for her keen attention to detail, and Lianna Farber for her kind encouragement through a long process. I would also like to thank the University of Minnesota English Department for travel and research grants that directly contributed to this project and the Graduate School for the generous support of a 2007-08 Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship. Fellow graduate students and members of the Medieval and Early Modern Research Group provided valuable support, advice, and collegiality. I would especially like to thank Elizabeth Ketner for her generous help and friendship, Ariane Balizet for sharing what she learned as she blazed the way through the dissertation and job search, Marcela Kostihová for encouraging my early modern interests, and Lindsay Craig for his humor and interest in my work. -

The Problem of Poverty in Piers Plowman

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2008 "Of beggeris and of bidderis what best be to doone?": The Problem of Poverty in Piers Plowman Dina Bevin Hess University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hess, Dina Bevin, ""Of beggeris and of bidderis what best be to doone?": The Problem of Poverty in Piers Plowman. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2008. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Dina Bevin Hess entitled ""Of beggeris and of bidderis what best be to doone?": The Problem of Poverty in Piers Plowman." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Thomas Heffernan, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Laura Howes, Joseph Trahern, Thomas Burman Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Dina Bevin Hess entitled “Of beggeris and of bidderis what best be to doone?: The Problem of Poverty in Piers Plowman.” I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. -

Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre

Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre Thomas Gaubatz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Thomas Gaubatz All rights reserved ABSTRACT Urban Fictions of Early Modern Japan: Identity, Media, Genre Thomas Gaubatz This dissertation examines the ways in which the narrative fiction of early modern (1600- 1868) Japan constructed urban identity and explored its possibilities. I orient my study around the social category of chōnin (“townsman” or “urban commoner”)—one of the central categories of the early modern system of administration by status group (mibun)—but my concerns are equally with the diversity that this term often tends to obscure: tensions and stratifications within the category of chōnin itself, career trajectories that straddle its boundaries, performative forms of urban culture that circulate between commoner and warrior society, and the possibility (and occasional necessity) of movement between chōnin society and the urban poor. Examining a range of genres from the late 17th to early 19th century, I argue that popular fiction responded to ambiguities, contradictions, and tensions within urban society, acting as a discursive space where the boundaries of chōnin identity could be playfully probed, challenged, and reconfigured, and new or alternative social roles could be articulated. The emergence of the chōnin is one of the central themes in the sociocultural history of early modern Japan, and modern scholars have frequently characterized the literature this period as “the literature of the chōnin.” But such approaches, which are largely determined by Western models of sociocultural history, fail to apprehend the local specificity and complexity of status group as a form of social organization: the chōnin, standing in for the Western bourgeoisie, become a unified and monolithic social body defined primarily in terms of politicized opposition to the ruling warrior class. -

Piers Plowman William Langland

Table of Content PIERS PLOWMAN 1. Historical and cultural context 2. English Literature 1150-1400 WILLIAM LANGLAND 3. Religious Context 4. William Langland 5. Piers Plowman 6. Translation of the text 7. Biblical background By Daniela Bartel and Irina Giesbrecht 8. Dialectal Diversity in ME 9. North vs. South Historical and cultural context Historical and cultural context The Hundred Year’s War (1337-1453) Rise of the English language open hostility with France (Patriotism?) The ‘Black Death’ (1348-1351) waning of the feudal system Statute of Pleading (1362) emerging of the ‘Middle Class’ increased social mobility Parliament opened in English (1362) economic and political opportunity (guilds) Peasants’ Revolt (1381) necessity for people to understand the law Lollards Historical and cultural context Historical and cultural context “[...] and that reasonably the said laws and customs The Peasants’ Revolt (1381) shall be most quickly learned and known, and consequences of the ‘Black Death’ better understood in the tongue used in the said about 30% of the population died realm, and by so much every man of the said realm poor suffered most may the better govern himself without offending of shortage of labor the law [...]” three poll taxes (1377, 1379, 1380) (Statute of Pleading 1362) Æ “general spirit of discontent arose” (Baugh & Cable) Historical and cultural context English Literature 1150-1400 Changes in social and economic life led to the literature = writing in general reestablishment of English 1150-1250: Period of Religious -

Graduate School of Arts and Letters (MA Courses)

Graduate School of Arts and Letters (MA Courses) 【Arts and Letters Studies】 *Subject* *CREDITS* Ancient Japanese Literature A (Prose) 4 Ancient Japanese Literature B (Poetry) 4 Medieval and Early Modern JapaneseLiterature A (Prose) 4 Medieval and Early Modern JapaneseLiterature B (Poetry) 4 Modern Japanese Literature A (Prose) 4 Modern Japanese Literature B (Poetry) 4 Japanese Language A (Ancient) 4 Japanese Language B (Modern) 4 Classical Chinese Literature 4 Library Science(Books as Cultural Objects) 4 Japanese Literature: Basic Studies A(Classical) 4 Japanese Literature: Basic Studies B(Modern) 4 English Expression I(Basic English Composition 2 English Expression Ⅱ(Advanced Writing Practice) 2 English Academic Writing I(Introduction to the Reserch Paper) 2 English Academic Writing Ⅱ(Practice in Writing Research Paper) 2 Topics in English Linguistics A(Linguistics for Literary Research) 4 Topics in English Linguistics B(Linguistics and Communicaton) 4 Medieval and Early Modern EnglishLiterature A (Medieval Literature) 4 Medieval and Early Modern EnglishLiterature B (Early Modern Literature) 4 Modern British Literature I(Modern British Literature) 2 Modern British Literature Ⅱ(Contemporary British Literature) 2 Modern American LiteratureⅠ(Modern) 2 Modern American Literature Ⅱ(Contemporary) 2 Topics in Modern British and AmericanLiterature I (British criticism) 2 Topics in Modern British and AmericanLiterature Ⅱ (American criticism) 2 Reading Modern British and AmericanLiteratureA(British and American Drama) 2 Reading Modern British and -

Piers Plowman, Anthony Trollope, and Charities Law Jill R

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2009 Nonprofits and Narrative: Piers Plowman, Anthony Trollope, and Charities Law Jill R. Horwitz UCLA School of Law, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/515 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Nonprofit Organizations Law Commons, and the Social Welfare Law Commons Recommended Citation Horwitz, Jill R. "Nonprofits nda Narrative: Piers Plowman, Anthony Trollope, and Charities Law." Mich. St. L. Rev. 2009, no. 4 (2009): 989-1016. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NONPROFITS AND NARRATIVE: PIERS PLOWMAN, ANTHONY TROLLOPE, AND CHARITIES LAW Jill Horwitz* 2009 MICH. ST. L. REV. 989 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ....................................................... 989 INTRODUCTION ...................................... ....... 990 I. LITERATURE IN NONPROFIT LAW: THE VISION OFPIERS PLO WMAN, THE STATUTE OF ELIZABETH, AND AMERICAN CHARITIES LAW ........ 995 A. The Statute of Elizabeth and Piers Plowman.................... 996 B. English and American Charities Law............. ..... 1000 11. NONPROFIT LAW IN LITERATURE: ST. CROSS HOSPITAL AND THE WARDEN ................................. ..... 1005 A. St. Cross Hospital ......................... ....... 1007 B. The Warden .......................................1009 CONCLUSION ................................................. 1015 ABSTRACT What are the narrative possibilities for understanding nonprofit law? Given the porous barriers between nonprofit law and the literature about it, there are many.