Network and Device Forensic Analysis of Android Social-Messaging Applications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elixir Journal

49022 Shabna. T.P and Priyanka.P / Elixir Library Sci. 112 (2017) 49022-49028 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Library Science Elixir Library Sci. 112 (2017) 49022-49028 Knowledge Sharing Over Instant Messaging Apps: A Study among IT Professionals, Malappuram, Kerala. Shabna. T.P1 and Priyanka.P2 1 Assistant Professor, Department of Library and Information Science, Farook College, Kozhikode, Kerala, India. 2 Head librarian, Scholars international academy, Sharjah, UAE. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Advances in information technology have resulted in the development of various Received: 13 October 2017; computer-mediated communication tools of which the Instant messenger (IM) is one of Received in revised form: the most prevalent. Instant messaging apps are widely used today for information 11 November 2017; sharing. The present study “Knowledge sharing over instant messaging apps: a study Accepted: 20 November 2017; among Kinfra community, Malappuram” is based on the importance of instant messaging apps and the authenticity of the information sharing via those apps which helps the users Keywords to determine its reliability. The need to conduct a study based on trustworthiness of the Knowledge Sharing, information sharing is desirable and useful for the users. A structured questionnaire is Instant message, used for collecting data which are personally distributed or sent through mail. The Web 2.0 applications, collected data are classified, analyzed. The investigator‟s conclusion on whether or not IT Professionals. instant messaging has negative effects on real-life social networks is, well, inconclusive. People have varying opinions on the topic, and there is evidence that can demonstrate both the pros and cons of using instant messaging. -

Cisco SCA BB Protocol Reference Guide

Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide Protocol Pack #60 August 02, 2018 Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com Cisco has more than 200 offices worldwide. Addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers are listed on the Cisco website at www.cisco.com/go/offices. THE SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION REGARDING THE PRODUCTS IN THIS MANUAL ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. ALL STATEMENTS, INFORMATION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN THIS MANUAL ARE BELIEVED TO BE ACCURATE BUT ARE PRESENTED WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. USERS MUST TAKE FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THEIR APPLICATION OF ANY PRODUCTS. THE SOFTWARE LICENSE AND LIMITED WARRANTY FOR THE ACCOMPANYING PRODUCT ARE SET FORTH IN THE INFORMATION PACKET THAT SHIPPED WITH THE PRODUCT AND ARE INCORPORATED HEREIN BY THIS REFERENCE. IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO LOCATE THE SOFTWARE LICENSE OR LIMITED WARRANTY, CONTACT YOUR CISCO REPRESENTATIVE FOR A COPY. The Cisco implementation of TCP header compression is an adaptation of a program developed by the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) as part of UCB’s public domain version of the UNIX operating system. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1981, Regents of the University of California. NOTWITHSTANDING ANY OTHER WARRANTY HEREIN, ALL DOCUMENT FILES AND SOFTWARE OF THESE SUPPLIERS ARE PROVIDED “AS IS” WITH ALL FAULTS. CISCO AND THE ABOVE-NAMED SUPPLIERS DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, THOSE OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT OR ARISING FROM A COURSE OF DEALING, USAGE, OR TRADE PRACTICE. IN NO EVENT SHALL CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, LOST PROFITS OR LOSS OR DAMAGE TO DATA ARISING OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THIS MANUAL, EVEN IF CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS HAVE BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. -

Security System for Mobile Messaging Applications Pejman Dashtinejad

Security System for Mobile Messaging Applications Pejman Dashtinejad Master of Science Thesis Stockholm, Sweden TRITA–ICT–EX-2015:2 Introduction | 1 Security System for Mobile Messaging Applications Pejman Dashtinejad 8 January 2015 Master of Science Thesis Examiner Professor Sead Muftic Department of ICT KTH University SE-100 44 Stockholm, Sweden TRITA–ICT–EX-2015:2 Abstract | iii Abstract Instant messaging (IM) applications are one of the most popular applications for smartphones. The IMs have the capability of sending messages or initiating voice calls via Internet which makes it almost cost free for the users to communicate with each other. Unfortunately, like any other type of applications, majority of these applications are vulnerable to malicious attacks and have privacy issues. The motivation for this thesis is the need to identifying security services of an IM application and to design a secure system for any mobile messaging application. This research proposes an E2EE (End-to-End Encryption) approach which provides a secure IM application design which protects its users with better integrity, confidentiality and privacy. To achieve this goal a research is conducted to investigate current security features of popular messaging applications in the mobile market. A list of requirements for good security is generated and based on those requirements an architecture is designed. A demo is also implemented and evaluated. Keywords: Mobile, Application, messaging, Chat, Encryption, Security Acknowledgments | v Acknowledgments First and foremost, thank you God to give me another chance to complete my higher education and to learn enormous skills and knowledge through all these years of study at the university. -

Enterprise Edition

Secure Communication. Simplified. SAFECHATS Problem Most companies use popular insecure email and ⛔ messaging services to communicate confidential information P The information flow within the Company is ⛔ disorganized Metadata is exposed and available to third-party ⛔ services SAFECHATS Introducing SAFECHATS Ultra-secure communication solution P Designed with security in mind SAFECHATS Why SAFECHATS? ✔ Information is always end-to-end encrypted by default P ✔ All-in-one communication suite: • Text messaging (one-on-one and group chats) • Voice calls • File transfers (no size and file type limits) SAFECHATS How does SAFECHATS solve the problem? ✔ Customizable white label solution ✔ Integrates with existing softwareP infrastructure ✔ Enterprise-wide account and contact list management, supervised audited chats for compliance SAFECHATS What makes SAFECHATS different? ✔ Your own isolated cloud environment or on-premise deployment P ✔ Customizable solution allows to be compliant with internal corporate security policies ✔ No access to your phone number and contact list SAFECHATS Screenshot Protection ✔ Notifications on iOS P ✔ DRM protection on Android SAFECHATS Identity Verification ✔ Protection from man-in-the-middle attacksP ✔ SMP Protocol SAFECHATS Privacy Features ✔ Show / hide messages and files P ✔ Recall messages and files ✔ Self-destructing messages and files SAFECHATS Additional Protection ✔ History retention control P ✔ Application lock: • PIN-code • Pattern-lock on Android devices • Touch ID on iOS devices SAFECHATS How does SAFECHATS -

REGUS Infographic Rev 1

The changing world of work New technologies are making it easier than ever to create intercontinental workforces and put our businesses on the global map. Employees are looking to use this new connectivity to create a better work-life balance and to make their daily output more efficient. Our latest survey shows how this change has already started, and reveals many of the ideas and motivations behind the flexible working revolution. Remote working on the rise 54% 83% 54% of global respondents 83% of executives plan to already work remotely 2.5 increase their use of flexible days per week or more. employment in the coming years, meaning these numbers are set to rise. The global context Working mothers, ageing populations and young workers seeking flexibility are changing the nature of the global workforce. 6% Returning mothers 13% Older workers remaining beyond their pensionable age 19% Outsourced suppliers 22% Part-time workers 29% Freelance workers 30% Consultants 33% Other The role of technology New Cloud technology, better Wi-Fi and modern communication tools mean we’re on call 24/7. Messaging tools used in the previous month: Whatsapp Skype Facebook Messenger WeChat Viber Snapchat LINE QQ MessageMe Tango ChatOn Hike Kakaotalk Nibuzz 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% Online flexible working tools used in the last month: Dropbox Google Drive Video conferencing Team Viewer WeTransfer Server cloud access Google Hangouts MS Remote Desktop Chrome remote desktop Virtual workgroups Apple remote desktop GoToMyPC LogMeIn Ignition Splashtop Wyse PocketCloud 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% Relishing remote work As these tech advances help employees take their work with them, they’re increasingly seeing the advantages of flexible workspaces. -

Network and Device Forensic Analysis of Android Social-Messaging Applications

DIGITAL FORENSIC RESEARCH CONFERENCE Network And Device Forensic Analysis Of Android Social-Messaging Applications By Daniel Walnycky, Ibrahim Baggili, Andrew Marrington, Frank Breitinger and Jason Moore Presented At The Digital Forensic Research Conference DFRWS 2015 USA Philadelphia, PA (Aug 9th - 13th) DFRWS is dedicated to the sharing of knowledge and ideas about digital forensics research. Ever since it organized the first open workshop devoted to digital forensics in 2001, DFRWS continues to bring academics and practitioners together in an informal environment. As a non-profit, volunteer organization, DFRWS sponsors technical working groups, annual conferences and challenges to help drive the direction of research and development. http:/dfrws.org Network'and'device'forensic'analysis'of'' Android'socialOmessaging'applica=ons' Daniel'Walnycky,'Ibrahim'Baggili,'Andrew'Marrington,' Jason'Moore,'Frank'Brei=nger' Graduate'Research'Assistant,'UNHcFREG'Member' Presen=ng'@'DFRWS,'Philadelphia,'PA,'2015' Agenda' • Introduc=on' • Related'work' • Methodology' • Experimental'results' • Discussion'and'conclusion' • Future'work' • Datapp' 2' Introduc=on' Tested'20'Android'messaging'apps'for'“low'hanging'fruit”'a.k.a'unencrypted'data:' • on'the'device,'in'network'traffic,'and'on'server'storage' Found'eviden=ary'traces:'passwords,'screen'shots,'text,'images,'videos,'audio,'GPS' loca=on,'sketches,'profile'pictures,'and'more…' 3' Related'work' • Forensic'value'of'smartphone'messages:' • Smartphones'may'contain'the'same'rich'variety'of'digital'evidence'which'might'be'found'on'a'computer' -

Digital Communications Protocols

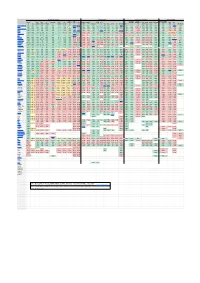

Security & Privacy Compatibility Features & Usability Sustainability E2E E2E Offline Local Decentralized Active Open Open On Anonymous E2E E2E Default Audit FIDO1 Desktop Mobile Apple AOSP Messages messaging File Audio Video Phoneless or Federated Open IETF [1] TLS Client Server Premise [2] Private Group [3] [4] / U2F Web Web Android iOS [5] Win macOS Linux *BSD Terminal MDM [6] [7] [8] Share Call Call [9] [10] Spec [11] Introduced Element/Matrix TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE PARTIAL TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE 2014 XMPP TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE PARTIAL [12]TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE [13] TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE 1999 NextCloud Talk TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE 2018 Wire TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE PARTIAL TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE 2014 Jami TRUE TRUE TRUE N/A [14] N/A TRUE TRUE FALSE [15] TRUE FALSE N/A [16] FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE PARTIAL PARTIAL[17] [18] 2016 Briar [19] TRUE TRUE TRUE N/A [20] N/A TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE N/A [21] FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE 2016 Tox TRUE TRUE TRUE -

Case No COMP/M.6281 - MICROSOFT/ SKYPE

EN Case No COMP/M.6281 - MICROSOFT/ SKYPE Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EC) No 139/2004 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(1)(b) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 07/10/2011 In electronic form on the EUR-Lex website under document number 32011M6281 Office for Publications of the European Union L-2985 Luxembourg EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 07/10/2011 C(2011)7279 In the published version of this decision, some information has been omitted pursuant to Article MERGER PROCEDURE 17(2) of Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets and other confidential information. The omissions are shown thus […]. Where possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a general description. PUBLIC VERSION To the notifying party: Dear Sir/Madam, Subject: Case No COMP/M.6281 - Microsoft/ Skype Commission decision pursuant to Article 6(1)(b) of Council Regulation No 139/20041 1. On 02.09.2011, the European Commission received notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of the Merger Regulation by which the undertaking Microsoft Corporation, USA (hereinafter "Microsoft"), acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)(b) of the Merger Regulation control of the whole of the undertaking Skype Global S.a.r.l, Luxembourg (hereinafter "Skype"), by way of purchase of shares2. Microsoft and Skype are designated hereinafter as "parties to the notified operation" or "the parties". I. THE PARTIES 2. Microsoft is active in the design, development and supply of computer software and the supply of related services. The transaction concerns Microsoft's communication services, in particular the services offered under the brands "Windows Live Messenger" (hereinafter "WLM") for consumers and "Lync" for enterprises. -

Protocol Filter Planning Worksheet, V7.X

Protocol Filter Planning Worksheet Websense Web Security Solutions (v7.x) Protocol filter (name): Applies to (clients): In policy (name): At (time and days): Legend Action Bandwidth Permit Block Network Protocol (percentage) Protocol Name Action Log Bandwidth Database SQL Net P B N P % File Transfer FTP P B N P % Gopher P B N P % WAIS P B N P % YouSendIt P B N P % Instant Messaging / Chat AOL Instant Messenger or ICQ P B N P % Baidu Hi P B N P % Brosix P B N P % Camfrog P B N P % Chikka Messenger P B N P % Eyeball Chat P B N P % 1 © 2013 Websense, Inc. Protocol filter name: Protocol Name Action Log Bandwidth Gadu-Gadu P B N P % Gizmo Project P B N P % Globe 7 P B N P % Gmail Chat (WSG Only) P B N P % Goober Messenger P B N P % Gooble Talk P B N P % IMVU P B N P % IRC P B N P % iSpQ P B N P % Mail.Ru P B N P % Meetro P B N P % MSC Messenger P B N P % MSN Messenger P B N P % MySpaceIM P B N P % NateOn P B N P % Neos P B N P % Netease Popo P B N P % netFM Messenger P B N P % Nimbuzz P B N P % Palringo P B N P % Paltalk P B N P % SIMP (Jabber) P B N P % Tencent QQ P B N P % TryFast Messenger P B N P % VZOchat P B N P % Wavago P B N P % Protocol Filter Planning Worksheet 2 of 8 Protocol filter name: Protocol Name Action Log Bandwidth Wengo P B N P % Woize P B N P % X-IM P B N P % Xfire P B N P % Yahoo! Mail Chat P B N P % Yahoo! Messenger P B N P % Instant Messaging File Attachments P B N P % AOL Instant Messenger or ICQ P B N P % attachments MSN Messenger attachments P B N P % NateOn Messenger -

Annual Report 2010 N T Ann Rrepo P

AnnualAnn RReReportpop rtt 2010 The Naspers Review of Governance and Financial Notice of Annual Group Operations Sustainability Statements General Meeting 2 Financial highlights 22 Review of operations 42 Governance 74 Consolidated 198 Notice of AGM 4 Group at a glance 24 Internet 51 Sustainability and company 205 Proxy form 6 Global footprInt 30 Pay television 66 Directorate annual financial 8 Chairman’s and 36 Print media 71 Administration and statements managing corporate information director’s report 72 Analysis of 16 Financial review shareholders and shareholders’ diary Entertainment at your fingertips Vision for subscribers To – wherever I am – have access to entertainment, trade opportunities, information and to my friends Naspers Annual Report 2010 1 The Naspers Review of Governance and Financial Notice of Annual Group Operations Sustainability Statements General Meeting Mission To develop in the leading group media and e-commerce platforms in emerging markets www.naspers.com 2 Naspers Annual Report 2010 The Naspers Review of Governance and Financial Notice of Annual Group Operations Sustainability Statements General Meeting kgFINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Revenue (R’bn) Ebitda (R’m) Ebitda margin (%) 28,0 6 496 23,2 26,7 6 026 22,6 09 10 09 10 09 10 Headline earnings Core HEPS Dividend per per share (rand) (rand) share (proposed) (rand) 8,84 14,26 2,35 8,27 11,79 2,07 09 10 09 10 09 10 2010 2009 R’m R’m Income statement and cash flow Revenue 27 998 26 690 Operational profit 5 447 4 940 Operating profit 4 041 3 783 Net profit attributable -

Skype Modile Download

Skype modile download Connect your way. Download the Skype mobile app for free, and talk, text, instant message, or video chat whenever, wherever. Get started.Skype Android · Skype Blackberry · iPhone · iPod touch. Call mobile and landline numbers – use the Skype app for Android to keep in touch with low-cost calls and SMS even if your friends aren't on Skype. Chat with. Make free Skype to Skype video and voice calls as well as send instant messages to friends and family around the world. Features: Call friends and family. The Skype you know and love has an all-new design, supercharged with a ton of new features and new ways to stay connected with the people you care about. Skype latest version: Skype, the telephone of the 21st century. Skype is the most popular application on the market for making video calls, mobile calls, and sen. Download this app from Microsoft Store for Windows 10, Windows 10 Mobile, HoloLens, Xbox One. See screenshots, read the latest customer reviews, and. Download Skype apps and clients across mobile, tablet, and desktop and across Windows, Mac, iOS, and Android. this video shows [HOW TO] Install and Create Skype Account on Mobile Phone. Skype for mobile is just about the same as Skype for desktop. That by itself is high praise - high-quality voice calls, convenient messaging, and low-cost phone. Download Skype For Every Mobile. Download Skype for All Mobiles at one place iPhone, Android, Symbian, Windows Phone, BlackBerry. All this will be available for anyone to see on Skype, except for your mobile number, which will be restricted to your own contacts. -

Resolving Mobile Communique App Using Classification of Data Mining Technique

ISSN:0975-9646 M.Mohamed Suhail et al, / (IJCSIT) International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technologies, Vol. 7 (2) , 2016, 583-587 Resolving Mobile Communique App Using Classification of Data Mining Technique M.Mohamed Suhail, Lecturer,Department of Computer Science, Jamal Mohamed College, Trichy, K.SyedKousarNiasi, Assistant Professor,Department of Computer Science, Jamal Mohamed College, Trichy, Abstract- A mobile app is a software application Data Mining refers to extracting or “mining” developed specifically for use on small, wireless computing knowledge from large amount of data.Many other terms devices, such as smartphones and tablets, rather than carry a similar or slightly different meaning to Data mining, desktop or laptop computers.On the Internet and mobile such as knowledge mining from data, knowledge app, chatting is talking to other people who are using the extraction, data/pattern analysis, Data archaeology, and Internet at the same time you are. Usually, this "talking" is Data dredging.Many people treat data mining as a synonym the exchange of typed-in messages requiring one site as the for another popularly used term, Knowledge Discovery repository for the messages (or "chat site") and a group of form Data, or KDD.Data mining has attracted a great deal users who take part from anywhere on the Internet.In this of attention in the information industry and in society as a work, we apply classification techniques of data mining whole in recent years, due to the wide availability of huge using a dataset of some mobile applications (eg. whatsapp, amounts of data and the imminent need for turning such Line…etc.,) to analyze the messengers.