West Elk Coal Mining Order

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1:13-Cv-01723-RBJ Document 91 Filed 06/27/14 USDC Colorado Page 1 of 36

Case 1:13-cv-01723-RBJ Document 91 Filed 06/27/14 USDC Colorado Page 1 of 36 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO Judge R. Brooke Jackson Civil Action No. 13-cv-01723-RBJ HIGH COUNTRY CONSERVATION ADVOCATES, WILDEARTH GUARDIANS, and SIERRA CLUB, Plaintiffs, v. UNITED STATES FOREST SERVICE, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, UNITED STATES BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR, DANIEL JIRÓN, in his official capacity as Regional Forester for the U.S. Forest Service’s Rocky Mountain Region, SCOTT ARMENTROUT, in his official capacity as Supervisor of the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests, and RUTH WELCH, in her official capacity as the Bureau of Land Management’s Colorado State Office Acting Director, Defendants, and ARK LAND COMPANY, INC., and MOUNTAIN COAL COMPANY, L.L.C., Intervenor-Defendants. ORDER The North Fork Valley in western Colorado is blessed with valuable resources. The area hosts several coal mines as well as beautiful scenery, abundant wildlife, and outstanding recreational opportunities. And as is sometimes the case in rich places like this, people disagree about how to manage the development of those resources. In the case before the Court, the plaintiff environmental organizations seek judicial review of three agency decisions that together 1 Case 1:13-cv-01723-RBJ Document 91 Filed 06/27/14 USDC Colorado Page 2 of 36 authorized on-the-ground mining exploration activities in a part of the North Fork Valley called the Sunset Roadless Area. These exploration activities are scheduled to begin on July 1, 2014. -

A Classification of Riparian Wetland Plant Associations of Colorado a Users Guide to the Classification Project

A Classification of Riparian Wetland Plant Associations of Colorado A Users Guide to the Classification Project September 1, 1999 By Gwen Kittel, Erika VanWie, Mary Damm, Reneé Rondeau Steve Kettler, Amy McMullen and John Sanderson Clockwise from top: Conejos River, Conejos County, Populus angustifolia-Picea pungens/Alnus incana Riparian Woodland Flattop Wilderness, Garfield County, Carex aquatilis Riparian Herbaceous Vegetation South Platte River, Logan County, Populus deltoides/Carex lanuginosa Riparian Woodland California Park, Routt County, Salix boothii/Mesic Graminoids Riparian Shrubland Joe Wright Creek, Larimer County, Abies lasiocarpa-Picea engelmannii/Alnus incana Riparian Forest Dolores River, San Miguel County, Forestiera pubescens Riparian Shrubland Center Photo San Luis Valley, Saguache County, Juncus balticus Riparian Herbaceous Vegetation (Photography by Gwen Kittel) 2 Prepared by: Colorado Natural Heritage Program 254 General Services Bldg. Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 [email protected] This report should be cited as follows: Kittel, Gwen, Erika VanWie, Mary Damm, Reneé Rondeau, Steve Kettler, Amy McMullen, and John Sanderson. 1999. A Classification of Riparian Wetland Plant Associations of Colorado: User Guide to the Classification Project. Colorado Natural Heritage Program, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO. 80523 For more information please contact: Colorado Natural Heritage Program, 254 General Service Building, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523. (970) -

Coal Fields of Northwestern Colorado and Northeastern Utah

COAL FIELDS OF NORTHWESTERN COLORADO AND NORTHEASTERN UTAH. By HOYT S. GALE. INTRODUCTION. NATURE OF THE PRESENT INVESTIGATION. This paper is a preliminary statement of the results of work in the coal fields of northwestern Colorado and northeastern Utah during the summer of 1907.° In 1905 a preliminary reconnaissance of the Yampa coal field, of Routt County, was made.6 In the summer of 1906 similar work was extended southwestward from the Yampa field, and the Danforth Hills and Grand Hogback coal fields, of Routt, Rio Blanco, and Garfield counties, were mapped.6 The work of the past season was a continuation of that of the two preceding years, extend ing the area studied westward through Routt and Rio Blanco counties, Colo., and including some less extensive coal fields in^Uinta County, Utah, and southern Uinta County, Wyo. ACCESSIBILITY. At present these fields have no_ railroad connection, although surveys for several projected lines have recently been made into the region. Of these lines, the Denver, Northwestern and Pacific Railway ("Moffat road") is under active construction in .the eastern part of Routt County and bids fair to push westward not far from the lower Yampa and White River fields in the near future. An extension of the Uintah Railway has been surveyed from Dragon to Vernal, Utah, crossing the projected route of the "MofFat road" near Green River. The Union Pacific Railroad has made a preliminary survey south from Rawlins, Wyo., intending to reach the Yampa Valley in the vicinity of Craig. a A more complete report combining the results of the preceding season's work in the Danforth Hills and Grand Hogback fields with those of last season's work as outlined here, together with detailed contour maps of the whole area, will be published as a (separate bulletin of the Survey. -

In the United States District Court for the District of Colorado

Case 1:19-cv-01920-RBJ Document 30 Filed 09/06/19 USDC Colorado Page 1 of 33 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO Civil Action No. 1:19-cv-1920 WILDEARTH GUARDIANS, HIGH COUNTRY CONSERVATION ADVOCATES, CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, SIERRA CLUB, and WILDERNESS WORKSHOP, Petitioners, v. DAVID L. BERNHARDT, Secretary, United States Department of the Interior, UNITED STATES OFFICE OF SURFACE MINING RECLAMATION AND ENFORCEMENT, JOSEPH R. BALASH, Assistant Secretary, Land and Minerals Management, United States Department of the Interior, GLENDA H. OWENS, Acting Director of the United States Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, DAVID BERRY, Regional Director, Western Region Office of the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, Federal Respondents, and MOUNTAIN COAL COMPANY, LLC, Intervenor-Respondents. FEDERAL RESPONDENTS’ OPPOSITION TO PETITIONERS’ OPENING BRIEF ON THE MERITS Case 1:19-cv-01920-RBJ Document 30 Filed 09/06/19 USDC Colorado Page 2 of 33 INTRODUCTION For the fourth time in ten years, Petitioner WildEarth Guardians, joined by other conservation groups, asks this Court to halt coal mining operations on National Forest System (“NFS”) lands in the North Fork Valley of western Colorado. In the first and third challenges, each alleging violations of the National Environmental Policy Act (“NEPA”), the Court rejected petitioners’ varied reasons why the Department of the Interior, the Department of Agriculture (“USDA”), or the United States Forest Service (“Service”) allegedly erred in their administrative proceedings. In the second challenge, High Country Conservation Advocates v. United States Forest Service, 52 F. Supp. 3d 1174 (D. Colo. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

Biological Assessment

Gunnison Basin Federal Lands Travel Management Plan - Biological Assessment BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT for GUNNISON BASIN FEDERAL LANDS TRAVEL MANAGEMENT PLAN Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests Gunnison Ranger District Prepared by Clay Speas (Wildlife, Fish and Rare Plants Program Lead) Michael Jackson (Gunnison RD Terrestrial Biologist – retired) INTRODUCTION: The purpose of this biological assessment is to determine the likely effects of the preferred alternative of the proposed Gunnison Basin Federal Lands Travel Management (GTM) project on federally listed species (endangered, threatened, and proposed) in the planning area. The federal lands addressed are National Forest System lands on the Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests (GMUG) that include the Gunnison and Paonia Ranger Districts and public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Gunnison Field Office. Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended, requires federal agencies to use their authorities to carry out programs to conserve endangered and threatened species, and to insure that actions authorized, funded, or carried out by them are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of listed or proposed species, or result in the destruction or adverse modification of their critical habitats. A Biological Assessment must be prepared for federal actions that are ―major construction activities‖ (also defined as a project significantly affecting the quality of the human environment as defined under NEPA) to evaluate the potential effects of the proposal on listed or proposed species. The contents of the BA are at the discretion of the federal agency, and will depend on the nature of the federal action (50 CFR 402.12(f)). -

West Elk Coal Mine: Complaint

Case 1:19-cv-01920 Document 1 Filed 07/02/19 USDC Colorado Page 1 of 50 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO Civil Action No. 1:19-1920 WILDEARTH GUARDIANS, HIGH COUNTRY CONSERVATION ADVOCATES, CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, SIERRA CLUB, and WILDERNESS WORKSHOP, Petitioners, v. DAVID L. BERNHARDT, in his official capacity as United States Secretary of the Interior; UNITED STATES OFFICE OF SURFACE MINING RECLAMATION AND ENFORCEMENT; JOSEPH BALASH, in his official capacity as Assistant Secretary of Land and Minerals Management, U.S. Department of the Interior, GLENDA OWENS, in her official capacity as Acting Director of U.S. Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement; DAVID BERRY, in his official capacity as Regional Director of U.S. Office of Surface Mining, Western Region; Federal Respondents. PETITION FOR REVIEW OF AGENCY ACTION INTRODUCTION 1. For the past thirty-seven years, the beautiful, forested mountains of Western Colorado have been under siege as the West Elk Coal Mine has metastasized across the landscape. Through a series of more than a dozen modifications to its federal coal leases and mining plans, West Elk has continually grown and now sprawls over nearly 20,000 acres of lands, including more than 13,000 acres of National Forest lands. In 2017, BLM and the Forest Case 1:19-cv-01920 Document 1 Filed 07/02/19 USDC Colorado Page 2 of 50 Service authorized the most recent 1,720 acre expansion of West Elk into the previously undisturbed Sunset Roadless Area. 2. This action challenges Federal Defendants’ recent approval of the “Mining Plan” authorizing the development of publicly owned coal across this new expansion. -

DWR Dam Safety Non-Jurisdictional Dam

DWR Dam Safety Non-Jurisdictional Dam DAMID Dam Name Other Dam Names WDID 400537 WEIR PARK 290148 GALLEGOS POND 400215 DELTA #3 020106 BOWLES #2 0203870 510220 HOMESTEAD HILLS POND HOMESTEAD HILLS HOA DAM 380246 SPAYD POND DAM 290131 REX S DAM 510113 LINKE 5103680 100104 BANNING LEWIS #1 020659 US36 POND OS-A3 670439 WHITE FARMS & SONS SOUTH FARM DAM 670415 Ausmus Pond 370210 LD #1 DAM LD POND 3704095 020238 MAGERS 0203321 110770 Droz Creek Pond #2 570205 Schaefermeyer #2 5703579 Page 1 of 640 10/03/2021 DWR Dam Safety Non-Jurisdictional Dam Physical Status DIV WD County PM Township Range Section Q160 Active 4 40 DELTA S 12.0 S 94.0 W 3 Active 7 29 ARCHULETA N 34.0 N 3.0 W 20 SE Active 4 28 DELTA S 13.0 S 96.0 W 27 Active 1 2 ADAMS S 1.0 S 65.0 W 6 NW Active 5 51 GRAND S 1.0 N 76.0 W 31 SW Active 5 38 GARFIELD S 7.0 S 87.0 W 20 SE Active 7 29 ARCHULETA N 35.0 N 2.0 W 11 SE Active 5 51 GRAND S 1.0 N 76.0 W 18 NW Active 2 10 EL PASO S 13.0 S 65.0 W 27 SE Active 1 2 BROOMFIELD S 1.0 S 69.0 W 34 Active 2 67 BENT S 22.0 S 49.0 W 26 2 67 PROWERS S 22.0 S 46.0 W 7 NE Active 5 37 EAGLE S 4.0 S 84.0 W 19 SE Active 1 2 ADAMS S 1.0 S 66.0 W 20 Active 2 11 CHAFFEE N 48.0 N 8.0 E 6 NE Active 6 57 ROUTT S 7.0 N 87.0 W 6 NE Page 2 of 640 10/03/2021 DWR Dam Safety Non-Jurisdictional Dam Q40 UTM x UTM y Location Accuracy Latdecdeg Longdecdeg NE 305326 4116697 GPS 37.176442 -107.192879 NE 524707.1 4427611.9 GPS 39.998337 -104.710572 NE 418985 4428643 User supplied 40.0041 -105.949161 SW 316652.5 4366267.8 GPS 39.426465 -107.130145 SW 320463 4127793 GPS -

USGS Quadrangle and Trails Illustrated Index

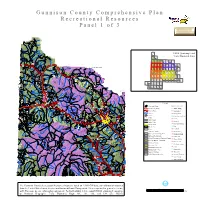

GunnisonGunnison CountyCounty ComprehensiveComprehensive PlanPlan RecreationalRecreational ResourcesResources PanelPanel 11 ofof 33 CO O C ESA N M SO NI GUN A S E M R E USGS Quadrangle and K A U Q B Trails Illustrated Index A T O I N C K A K L L P E N N I S IN I A S A A T A T N S K K P T E L A A N N U L E L O E E U U B E P P C O B O R M K N M S N E M A S N E R D L IR M A O D O L O Y N A M Y E U R A P B H W W C A H E E O M N D N N S N I IR I 265B O A V T T R N L D 47 E U U S K R 56 E S S O F S E A E C E R M Y I A D V E R O P R T L A J H C N R M IA - T L I E A O N E O N A S N I B L F H O L - G AR I A P N A L E E I T 265 P H P L I N !9 E O A P W McClure C T U 4567 I O PITKIN R C R O A 133 131 I M K M N O E I V Pass SNOWMASS MOUNTAIN S A G N A S I R E N E T E A P T A P A L T N S !( H R L T N U E T E X A I E E U U O R L T B T O P A W I M K U GUN O D M Y !F NIS K C S R ON S CO AXT E C E C A . -

ANNUAL REPORT Water Year Irrigation Diuision No

ANNUAL REPORT 1980 Water Year Irrigation Diuision No 4 February 10 1981 Jeris A Danielson State Engineer Division of Water Resources 1313 Sherman Street Denver Colorado 80203 Dear Mr Danielson On behalf of the office and field personnel of Irrigation Division Four I submit herewith the Annual Report for 1980 Special recognition is made for highly competent Division Four Staff from which the various responsibilities of w ter management have been attended to in a professional manner Respectfully submitted i alp tl V Kelling l Division Engineer RVK j d TABLE OF CONTENTS Pa e I Introductory Statement 1 Special Note 7 II Pers onnel 9 14 III Water Supply 15 36 A Snaw Pack 15 16 B Precigitation 16 17 C Floods 18 D Water Budget 18 19 E Underground Water 19 20 F Transmountain and Transbasin Diversions 21 22 G Annual Diversion and Storage Records 23 24 H Reservoir Storage 24 36 Special Note 18 25 IV Agriculture 37 42 V Campacts and Court Stipalations 43 VI Dams 43 45 Reservoir Restrictions 44 Livestock Water Tanks 45 C VII Water Rights 46 47 A Tabulation 46 B Referee Findings and Decrees 46 VIII Organizations 48 54 A Water Conservation and Conservancy Districts 48 B Water Related Organizations 49 54 IX Water Ca issioner s u ary 55 61 Division s Summary Annual Summary Latest Format 62 A Direct Flow Diversions 63 B Storage Report 64 Miscellaneous Reports and Tables 55 74 1 Budget Workload and Statistieal Indicators 65 2 Uncompahgre Project 1979 Season 66 3 Water Supply Outlook May 1979 6 7 70 4 Table of Organization 71 5 Areas of Responsibility Field -

A Preliminary Habitat Type Classification

Historic, Archive Document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. i United States JUjj Department of Forest Vegetation of the Agriculture Gunnison and Parts of the Forest Service Uncompahgre National Forests: Rocky Mountain Forest and Range A Preliminary Habitat Experiment Station Type Classification Fort Collins, r- -.v.---. Colorado 80526 05 Vera Komarkova, Robert R. Alexander, and Barry^^Johrt^on General Teclinical Report RM-163 MS 908826 USDA Forest Service August 1988 General Technical Report RM-163 Forest Vegetation of the Gunnison and Parts of the Uncompahgre National Forests: A Preliminary Habitat Type Classification Vera Komarkova, Research Associate University of Colorado Robert R. Alexander, Chief Silviculturist Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station^ Barry C. Johnston, Ecologist USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region Abstract A vegetation classification based on a combination of concepts and methods developed by Braun-Blanquet and Daubenmire was used to identify 37 tentative forest habitat types on the Gunnison National Forest. Woodland habitat types comprised two series with a total of 3 habitat types, and forest habitat types included nine series with a total of 34 habitat types. A key to identify the habitat types is provided and the management implications associated with each are discussed. Cover Photo.— Subalpine forests near Los Pinos Pass, Gunnison National Forest. Headquarters is in Fort Collins, in cooperation with Colorado State University. Contents Page -

July 24, 2017 Mr. Scott Armentrout, Supervisor GMUG

July 24, 2017 Mr. Scott Armentrout, Supervisor GMUG National Forest 2250 Highway 50 Delta, CO 81416 Via Email: [email protected] Via web: https://cara.ecosystem-management.org/Public/CommentInput?Project=32459 Re: Comments of High Country Conservation Advocates et al. on the Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement on Federal Coal Lease Modifications COC- 1362 & COC-67232 (Project #32459) Dear Supervisor Armentrout: Thank you for this opportunity to submit comments on the supplemental draft environmental impact statement (SDEIS) on the Forest Service’s proposal to consent to Bureau of Land Management (BLM) modifying Federal Coal Leases COC-1362 and COC-67232 by adding 800 and 920 acres, respectively, to those leases. The SDEIS also addresses the impacts of Arch Coal’s Sunset Trail Area Coal Exploration Plan within the Lease Modifications area. This letter is sent on behalf of five conservation groups, all of whom have a longstanding interest in the protection and wise stewardship of roadless national forest lands and our climate. Given the important roadless, wilderness, wildlife and other values at stake, and the climate impacts of allowing Arch Coal to bulldoze over 6 miles of roads in publicly owned backcountry forests so that it might profit from mining and burning 17.6 million tons of coal, we urge the Forest Service and BLM to reject Arch’s proposal, and instead adopt the “environmentally preferred alternative”: the No Action Alternative.1 For the reasons set forth below, the undersigned groups, among other things,