Mark the Evangelist: His African Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Gospel of Mark

The Gospel of MARK Part of the Holy Bible A Translation From the Greek by David Robert Palmer https://bibletranslation.ws/palmer-translation/ ipfs://drpbible.x ipfs://ebibles.x To get printed edtions on Amazon go here: http://bit.ly/PrintPostWS With Footnotes and Endnotes by David Robert Palmer July 23, 2021 Edition (First Edition was March 1998) You do not need anyone's permission to quote from, store, print, photocopy, re-format or publish this document. Just do not change the text. If you quote it, you might put (DRP) after your quotation if you like. The textual variant data in my footnote apparatus are gathered from the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament 3rd Edition (making adjustments for outdated data therein); the 4th Edition UBS GNT, the UBS Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, ed. Metzger; the NA27 GNT; Swanson’s Gospels apparatus; the online Münster Institute transcripts, and from Wieland Willker’s excellent online textual commentary on the Gospels. The readings for Φ (043) I obtained myself from Batiffol, Source gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France. PAG E 1 The Good News According to MARK Chapter 1 John the Baptizer Prepares the Way 1The beginning of the good news about Jesus Christ, the Son of God.1 2As2 it is written in the prophets: 3 "Behold, I am sending my messenger before your face, who will prepare your way," 3"a voice of one calling in the wilderness, 'Prepare the way for the Lord, make the paths straight for him,'4" 4so5 John the Baptizer appeared in the wilderness, proclaiming a baptism of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. -

Divine Liturgy

THE DIVINE LITURGY OF OUR FATHER AMONG THE SAINTS JOHN CHRYSOSTOM H QEIA LEITOURGIA TOU EN AGIOIS PATROS HMWN IWANNOU TOU CRUSOSTOMOU St Andrew’s Orthodox Press SYDNEY 2005 First published 1996 by Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia 242 Cleveland Street Redfern NSW 2016 Australia Reprinted with revisions and additions 1999 Reprinted with further revisions and additions 2005 Reprinted 2011 Copyright © 1996 Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia This work is subject to copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted without prior written permission from the publisher. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data The divine liturgy of our father among the saints John Chrysostom = I theia leitourgia tou en agiois patros imon Ioannou tou Chrysostomou. ISBN 0 646 44791 2. 1. Orthodox Eastern Church. Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. 2. Orthodox Eastern Church. Prayer-books and devotions. 3. Prayers. I. Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia. 242.8019 Typeset in 11/12 point Garamond and 10/11 point SymbolGreek II (Linguist’s Software) CONTENTS Preface vii The Divine Liturgy 1 ïH Qeiva Leitourgiva Conclusion of Orthros 115 Tevlo" tou' ÒOrqrou Dismissal Hymns of the Resurrection 121 ÆApolutivkia ÆAnastavsima Dismissal Hymns of the Major Feasts 127 ÆApolutivkia tou' Dwdekaovrtou Other Hymns 137 Diavforoi ÓUmnoi Preparation for Holy Communion 141 Eujcai; pro; th'" Qeiva" Koinwniva" Thanksgiving after Holy Communion 151 Eujcaristiva meta; th;n Qeivan Koinwnivan Blessing of Loaves 165 ÆAkolouqiva th'" ÆArtoklasiva" Memorial Service 177 ÆAkolouqiva ejpi; Mnhmosuvnw/ v PREFACE The Divine Liturgy in English translation is published with the blessing of His Eminence Archbishop Stylianos of Australia. -

The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English

The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English A Revised Critical Edition Translated by Anna M. Silvas A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical Press Cover design by Jodi Hendrickson. Cover image: Wikipedia. The Latin text of the Regula Basilii is keyed from Basili Regula—A Rufino Latine Versa, ed. Klaus Zelzer, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum, vol. 86 (Vienna: Hoelder-Pichler-Tempsky, 1986). Used by permission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences. Scripture has been translated by the author directly from Rufinus’s text. © 2013 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, micro- fiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Basil, Saint, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 329–379. The Rule of St Basil in Latin and English : a revised critical edition / Anna M. Silvas. pages cm “A Michael Glazier book.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8146-8212-8 — ISBN 978-0-8146-8237-1 (e-book) 1. Basil, Saint, Bishop of Caesarea, approximately 329–379. Regula. 2. Orthodox Eastern monasticism and religious orders—Rules. I. Silvas, Anna, translator. II. Title. III. Title: Rule of Basil. -

Anselm's Cur Deus Homo

Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo: A Meditation from the Point of View of the Sinner Gene Fendt Elements in Anselm's Cur Deus Homo point quite differently from the usual view of it as the locus classicus for a theory of Incarnation and Atonement which exhibits Christ as providing the substitutive revenging satisfaction for the infinite dishonor God suffers at the sin of Adam. This meditation will attempt to bring out how the rhetorical ergon of the work upon faith and conscience drives the sinner to see the necessity of the marriage of human with divine natures offered in Christ and how that marriage raises both man and creation out of sin and its defects. This explanation should exhibit both to believers, who seek to understand, and to unbelievers (primarily Jews and Muslims), from a common root, a solution "intelligible to all, and appealing because of its utility and the beauty of its reasoning" (1.1). Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo is the locus classicus for a theory of Incarnation and Atonement which exhibits Christ as providing the substitutive revenging satisfaction for the infinite dishonor God suffers at the sin of Adam (and company).1 There are elements in it, however, which seem to point quite differently from such a view. This meditation will attempt to bring further into the open how the rhetorical ergon of the work upon “faith and conscience”2 shows something new in this Paschal event, which cannot be well accommodated to the view which makes Christ a scapegoat killed for our sin.3 This ergon upon the conscience I take—in what I trust is a most suitably monastic fashion—to be more important than the theoretical theological shell which Anselm’s discussion with Boso more famously leaves behind. -

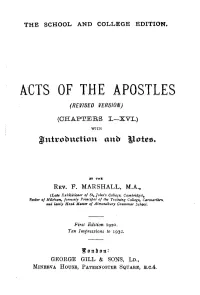

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

Letters. with an English Translation by Roy J. Deferrari

THE XOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY T. E. PAGE, C.H., MTT.D. E. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. W. H. D. ROUSE, litt.d. SAINT BASIL THE LETTERS IV SAINT BASIL, t ^e Gr. THE LETTERS WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY ROY J. DEFERRARI, Ph.D. OF THE CATHOLIC ITNIVERSITY OF AMERICA ADDRESS TO YOUNG MEN ON READING GREEK LITERATURE WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY ROY JOSEPH DEFERRARI AND MARTIN R. P. McGUIRE OF THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA IN FOUR VOLUMES IV LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MCMXXXIV Printed in Oreat Britain PREFATORY NOTE The present volume marks the fourth and last of the collected Letters of St. Basil in the Loeb Classical Library and includes Letters CCXLIX to CCCLXVIIL Of these, the last two are here added to the corpus of Basil's letters for the first time. Furthermore, many of the later letters of this volume appear here with an English translation for the first time. Most of the dubia and spuria are included in this volume, and wherever possible I have attempted to summarize the best scholarly opinion regarding their authenticity and to add such new evidence as I have been able to find. The text of this fourth volume has been treated exactly as that of the second and third volumes. Letters CCXLIX to CCCLVI, exclusive of Letter CCCII, appear in the MS. known as Coisslinianus 237 (sig. = E), and do not occur in any of the other MSS. collated by me. Letters CCCII and CCCLVII to CCCLXVIII appear in no MS. -

St Mark the Evangelist April 25 2021 Worship Bulletin

Service of Daily Prayer St. Mark the Evangelist Athens Lutheran Church - Athens, TN April 25, 2021 St. Mark, the Evangelist Today, the Holy Church celebrates the Festival of St. Mark, Evangelist, author of the second Gospel and companion of St. Peter and St. Paul. John Mark was cousin to the apostle Barnabas. His mother’s home in Jerusalem was a meeting place for the Early Church. “The weak by grace made strong” in the hymn stanza refers to the famous incident recorded in Acts 15. Though John Mark had begun the first missionary journey with Paul and Barnabas, he did not finish it. We’re not told exactly why he returned, but it was clearly without Paul’s blessing. Barnabas, the true son of encouragement, was all for giving the young man a second chance when he and Paul determined to begin a second journey. Paul adamantly refused. The disagreement became so sharp that they ended up splitting ways. Paul took Silas and went to Asia Minor; Barnabas took Mark and went to Cyprus. If that were the end of the story it would be sad indeed. What a comfort, then, to read in St. Paul’s final letter, 2 Timothy 4:11: “Luke alone is with me. Get Mark and bring him with you, for he is very useful to me for ministry.” Though a veil of silence remains over the details of how it happened, the two were reconciled before Paul’s death and the Church’s ministry strengthened all the more. Additionally, Peter, writing from Rome, would say, “She who is at Babylon [code name for Rome, as in Revelation], who is likewise chosen, sends you greetings, and so does Mark, my son.” Thus Mark ministered not only with the apostles Barnabas and Paul but with Peter too. -

Read Online (PDF)

BREAKING THE BREAD OF THE WORD A LECTIO DIVINA Approach to the Weekday Liturgy PROPER OF SAINTS January 25: Conversion of Saint Paul, Apostle (n. 109) January 25: Saints Timothy and Titus (n. 110) February 22: Chair of Saint Peter (n. 111) April 25: Saint Mark Evangelist (n. 112) May 1: Saint Joseph the Worker (n. 113) May 14: Saint Matthias, Apostle (n. 114) June 11: Saint Barnabas, Apostle (n. 115) July 3: Saint Thomas (n. 116) July 22: Saint Mary Magdalene (n. 117) July 25: Saint James, Apostle (n. 118) June 19: Saint Mary Magdalene (n. 119) August 10: Saint Lawrence (n. 120) August 24: Saint Bartholomew, Apostle (n. 121) August 29: Passion of John the Baptist (n. 122) September 8: Nativity of Blessed Virgin Mary (n. 123) September 15: Our Lady of Sorrows (n. 124) September 21: Saint Matthew, Apostle and Evangelist (n. 125) September 29: Saints Michael, Gabriel and Raphael, Archangels (n. 126) October 2: Guardian Angels (n. 127) October 18: Saint Luke Evangelist (n. 128) October 28: Saints Simon and Jude, Apostles (n. 129) November 30: Saint Andrew, Apostle (n. 130) December 12: Our Lady of Guadalupe (n. 131) Prepared by Sr. Mary Margaret Tapang, PDDM *** Text of the Cover Page ends here. *** A Lectio Divina Approach to the Weekday Liturgy BREAKING THE BREAD OF THE WORD (n. 109) January 25: CONVERSION OF PAUL, APOSTLE “JESUS SAVIOR: He Transforms His Persecutor Saul into an Apostle” BIBLE READINGS Acts 22:3-16 or Acts 9:1-22 // Mk 16:15-18 I. BIBLICO-LITURGICAL REFLECTIONS: A Pastoral Tool for the LECTIO The feast of the Conversion of Saint Paul provides wonderful insights into his spiritual journey. -

April 8, 2018 Sunday of Divine Mercy Dimanche De La Miséricorde Divine CALENDAR of EVENTS “We Are More Than Sunday Morning”

65 W. 138th Street, New York, NY 10037 (212) 281.4931 One of The Catholic Parishes of the Central Harlem Deanery MISSION STATEMENT : We are more than Sunday Morning. We are worship, service, and fellowship. We are a community of Faith. All are Welcome ! MASS SCHEDULE : Saturday - 5:00 pm Sunday - 8:30 am 11:15 am 5:00 pm (French) Tue-Fri - 12:15pm Friday- 8am to 7pm - Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament Confessions-anytime by request Website: stmark138.com Email: [email protected] Facebook: St. Mark Church - Harlem Fax: 212.491.6803 April 8, 2018 Sunday of Divine Mercy Dimanche de la Miséricorde Divine CALENDAR OF EVENTS “We are more than Sunday morning” PRAYER CORNER Friends and family, as a reminder you can remember your loved ones through a mass inten- Please remember in your prayers: Gloria Palmer, Doris Moss, Henry Isom, Eleanor Jefferson, Ishmael Jackson, tion. It is a beautiful way to honor them. You can Willa Mae Washington, Tyrone Randell, DeCosta Stroble, have an intention said at mass any day of the Elizabeth Young, Tracey Bultron-Lewis, Myrtle Patterson, week or weekend. What a beautiful way to Walter Thompson, Rivanna Johnson, Dorothy Allen, remember and honor those we love, living or de- Kenny Love, Birdell Cotton , Muriel William-Young, Rose Jean Jacques Mandazou, Shirley Cuevas, Pearl Rollerson, ceased. At your request, we have beautiful mass Debra Woodland-Lee, Lottie Culpepper, Violet cards. If you would like a mass intention call or Stephenson, Louise Owens, Louisa John visit the office to schedule. If your name or the name of a loved one has been omitted or needs to be added to the prayer corner, please call the office to be placed on Religious Education Classes will be every other the list for another month. -

St. Mark the Evangelist Catholic Church Fourth Sunday of Advent | December 20, 2020 Cuarto Domingo De Adviento | 20 De Diciembre, 2020

5601 South Flamingo Road Southwest Ranches, Florida 33330 Tel 954.434.3777 • Fax 954.434.3125 • www.stmarkparish.org • Email: [email protected] St. Mark The Evangelist Catholic Church Fourth Sunday of Advent | December 20, 2020 Cuarto Domingo de Adviento | 20 de Diciembre, 2020 W E L C O M E ! ~ B I E N V E N I D O S ! HOLY MASS ● SANTA MISA Church Information (*Streaming times) PASTORAL STAFF Monday - Friday: 7:00 am & 8:30 am* Pastor: Rev. Jaime H. Acevedo English - Parish Center Parochial Vicar: Rev. Paul VI Karenga Saturday: 8:30 am Deacons: Rev. Mr. Vincent Farinato, English - Parish Center Rev. Mr. John Lorenzo, Rev. Mr. Jose Escudero, Saturday Vigil: 5:00 pm* English - Church Rev. Mr. José M. Gordillo, This is a temporary Vigilia: 7:00 pm Español - Iglesia schedule of Masses Rev. Mr. Jesús Tosco Sunday: 8:00 am & 10:30 am* † Este es un horario English - Church temporal de misas PARISH OFFICE HOURS 1:00 pm* Español - Iglesia Mon - Thurs: 9:00 am - 8:00 pm (Closed 12:00 noon - 1:00 pm) HOLY MASS INTENTIONS † Friday: 9:00 am - 3:00 pm Saturday: Closed Sunday, December 20 Sunday: 8:30 am - 12:30 pm 8:00 am & 10:30 am: † Nani Perez, † Louis Gomez, † People of St. Mark, † Michael Torlone † Jimmy Maguddatu ST. MARK SCHOOL 1:00 pm: † Haydee Rojas De Franco, † Virgilio Rafael Gonzalez School Principal: Teresita Wardlow Monday, December 21 Tel: 954-434-3777 7:00 am: † Hernando Matiz & Fam, † Anna & Devasia Ouseph Web: school.stmarkparish.org 8:30 am: † Rose Fontana, Poor Souls in Purgatory † Tuesday, December 22 RELIGIOUS EDUCATION 7:00 am: † Juana Valle, † Anna & Devasia Ouseph 8:30 am: † Sabina Roach, † Fouad & Rahme Abourizk Director of Religious Education: Donna Villavisanis Wednesday, December 23 Tel: 954-252-9899 7:00 am: (L) Luis Iglesias, Poor Souls in Purgatory Web: faithformation.stmarkparish.org 8:30 am: † Leon Lathrop, † Boleslaw Tokarz † Thursday, December 24 3:00 pm: † Edward Amos, † Jean & Charles Pariseau ADORATION ● ADORACION 5:00 pm: † Julia Brickman Gillen, † Teresa & Gabriel Perera Monday - Friday: 9:00 am - 10:00 am 7:00 pm: People of St. -

Basil of Caesarea, Canonical Letters (Letters 188, 199, 217) Translated

Selection [DRAFT] Basil of Caesarea, Canonical Letters (Letters 188, 199, 217) Translated by Andrew Radde-Gallwitz, forthcoming in Ellen Muehlberger, ed. The Cambridge Edition of Early Christian Writings, Volume Two: Practice (Cambridge UP). INTRODUCTION Basil of Caesarea (ca. 330-378) left behind one of the largest bodies of writing from the early Christian period, including monastic legislation, homilies, theological treatises, and an extensive correspondence. The three letters translated here are traditionally known as his canonical letters, and were read as authoritative documents in Byzantine tradition. The letters make no attempt to codify all of church law, but rather respond to specific queries sent by Basil’s protégé, Amphilochius of Iconium, who became a significant theologian in his own right. It is crucial to bear in mind that Amphilochius has asked for Basil’s judgment regarding specific cases that have come up in Amphilochius’ church in Iconium. Basil comments on cases dealing with murder, sex and marriage, the consultation of seers, and the conversions of heretics and schismatics. (Canon 1, incidentally, contains one of the classic statements of the differences between heresy and schism.) Precedent is decisive for Basil’s casuistry, and the reader can see his frequent appeal to the prior tradition of canonical legislation. By Basil’s time, this tradition included canons from individual bishops and rulings from church councils such as Elvira, Nicaea, and Laodicea, though Basil’s knowledge and use of these councils’ disciplinary decrees is uncertain. While conciliar legislation begins in the early fourth century, the individual episcopal canons on which Basil draws go back to the mid-third century: Basil mentions Dionysius of Alexandria, Cyprian of Carthage, and his own predecessor Firmilian of Caesarea. -

Mark the Evangelist 1 Mark the Evangelist

Mark the Evangelist 1 Mark the Evangelist "Saint Mark" redirects here. For other uses, see Saint Mark (disambiguation). Mark the Evangelist Evangelist, Martyr Born 1st century AD Cyrene, Pentapolis of North Africa, according to Coptic tradition Died traditionally 68 AD Honored in All Christian churches Feast April 25 Patronage Barristers, Venice, Egypt, Mainar is the purported (מרקוס :Mark the Evangelist (Latin: Mārcus; Greek: Μᾶρκος; Coptic: Μαρκοϲ; Hebrew traditional author of the Gospel of Mark. One of the Seventy Disciples, Mark founded the Church of Alexandria, one of the original three main episcopal sees of Christianity. His feast day is celebrated on April 25, and his symbol is the winged lion. Mark's identity According to William Lane (1974), an "unbroken tradition" identifies Mark the Evangelist with John Mark, and John Mark as the cousin of Barnabas.[1] However, Hippolytus of Rome in On the Seventy Apostles distinguishes Mark the Evangelist (2 Tim 4:11), John Mark (Acts 12:12, 25; 13:5, 13; 15:37), and Mark the cousin Mark the Evangelist symbol is the winged lion of Barnabas (Col 4:10; Phlm 1:24). According to Hippolytus, they all belonged to the "Seventy Disciples" who were sent out by Jesus to saturate Judea with the gospel (Luke 10:1ff.). However, when Jesus explained that his flesh was "real food" and his blood was "real drink", many disciples left him (John 6:44–6:66), presumably including Mark. He was later restored to faith by the apostle Peter; he then became Peter’s interpreter, wrote the Gospel of Mark, founded the church of Africa, and became the bishop of Alexandria.