Sector Assessment (Summary): Public Sector Management1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORDER SHEET in the HIGH COURT of SINDH, KARACHI C.P No

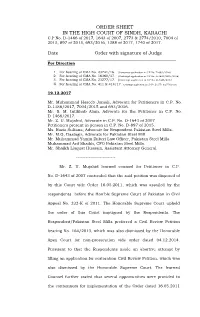

ORDER SHEET IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH, KARACHI C.P No. D-1466 of 2017, 1643 of 2007, 2773 & 2774/2010, 7004 of 2015, 897 of 2015, 693/2016, 1388 of 2017, 1740 of 2017. _________________________________________________________ Date Order with signature of Judge ________________________________________________________ For Direction 1. For hearing of CMA No. 23741/16. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-693/2016) 2. For hearing of CMA No. 16360/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-1643/2007/2016) 3. For hearing of CMA No. 23277/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-1466/2017) 4. For hearing of CMA No. 411 & 414/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-2773 & 2774/2010) 19.12.2017 Mr. Muhammad Haseeb Jamali, Advocate for Petitioners in C.P. No. D-1388/2017, 7004/2015 and 693/2016. Mr. S. M. Intikhab Alam, Advocate for the Petitioner in C.P. No. D-1466/2017. Mr. Z. U. Mujahid, Advocate in C.P. No. D-1643 of 2007 Petitioners present in person in C.P. No. D-897 of 2015. Ms. Razia Sultana, Advocate for Respondent Pakistan Steel Mills. Mr. M.G, Dastagir, Advocate for Pakistan Steel Mill Mr. Muhammad Yamin Zuberi Law Officer, Pakistan Steel Mills. Muhammad Arif Shaikh, CFO Pakistan Steel Mills. Mr. Shaikh Liaquat Hussain, Assistant Attorney General. ------------------------- Mr. Z. U. Mujahid learned counsel for Petitioner in C.P. No. D-1643 of 2007 contended that the said petition was disposed of by this Court vide Order 16.05.2011, which was assailed by the respondents before the Hon’ble Supreme Court of Pakistan in Civil Appeal No. -

Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (Ppra) Contract Award

ATTACHMENT – I (See regulation 2) PUBLIC PROCUREMENT REGULATORY AUTHORITY (PPRA) CONTRACT AWARD PROFORMA – I To Be Filled And Uploaded on PPRA Website In Respect of All Public Contracts of Works, Services and Goods Worth Fifty Million or More NAME OF THE ORGANIZATION Privatisation Commission__ FEDERAL / PROVINCIAL GOVT. Federal Government_________ TITLE OF CONTRACT Financial Advisory Services Agreement___ TENDER NUMBER TS233834E ______ BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF CONTRACT Divestment of Government of Pakistan shareholding in Pakistan Steel Mills Corporation (PSMC) TENDER VALUE Approx. US$ 3.6 Million______ ENGINEER’S ESTIMATE N/A_________________________ (for civil Works only) ESTIMATED COMPLETION PERIOD December, 2015 WHETHER THE PROCUREMENT WAS INCLUDED IN ANNUAL PROCUREMENT PLAN? _________ N/A _____________Yes / No ADVERTISEMENT : (i) PPRA Website____16-02-2015____ TS233834E _____Yes / No (Federal Agencies) (If yes give date and PPRA’s tender number) (ii) News Papers_Yes (List of Newspapers / Press (Annex – I) Yes / No (If yes give names of newspapers and dates) TENDER OPENED ON (DATE & TIME) _____14-04-2015 (1100 Hrs)____ NATURE OF PURCHASE Local and International _ (Local / International) EXTENSION IN DUE DATE (If any)_____ Yes ____Yes / No -: 2 :- NUMBER OF TENDER DOCUMENTS SOLD 2 (Attach list of Buyers) WHETHER QUALIFICATION CRITERIA WAS INCLUDED IN BIDDING/TENDER DOCUMENTS _Yes__Yes / No (If yes enclose a copy). WHETHER BID EVALUATION CRITERIA WAS INCLUDED IN BIDDING/TENDER DOCUMENTS_ Yes __Yes / No (If yes enclose a copy). -

Tundra Case – Aisha Steel Mills Limited

TUNDRA CASE AISHA STEEL MILLS LIMITED PAKISTAN TUNDRA CASE AISHA STEEL MILLS LIMITED TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION 3 STEEL INDUSTRY IN PAKISTAN 3 RATIONALE FOR TUNDRA’S INVESTMENT 4 REFERENCES 4 COMPANY FACTS AND ENGAGEMENT 5 DISCLAIMER 6 Capital invested in a fund may either increase or decrease in value and it is not certain that you will be able to recover all of your investment. Historical return is no guarantee of future return. The value of invested capital may vary substantially due to the composition of the fund and the investment process used by the fund manager. The Full Prospectus, KIID etc. are available on our homepage. You can also contact us to receive the documents free of charge. See full disclaimer on www.tundrafonder.se 2 TUNDRA CASE AISHA STEEL MILLS LIMITED INTRODUCTION In early 2017, Aisha Steel Mills Limited (ASML) was bought on behalf of three of Tundra Fonder’s funds. The first and only exposure in the steel market in Pakistan, ASML constitutes an interesting case study of a sustainable mid-sized steel company in the country. Factors such as continued economic growth in the country, an increased demand for steel, and regulations promoting domestic manufacturing created a favorable investment environment. The iron and steel sector is one of the most energy-intensive in the world. With a global capacity of just over 1.6bn tonnes (2016), the sector relies heavily on water, energy and labour [1]. Materials needed to make steel include iron ore, coal, limestone and recycled steel. Steel production methods have evolved significantly since the steel industry first began in the late 19th century. -

Muhammad Nawaz Khan & Beenish Altaf Introduction

Pakistan-Russia RapprochementIPRI Journal XIII, and no.Current 1 (Winter Geo-Politics 2013): 125-134 125 PAKISTAN-RUSSIA RAPPROCHEMENT AND CURRENT GEO-POLITICS ∗ Muhammad Nawaz Khan & Beenish Altaf Abstract The trend of improvement seen lately in Pakistan-Russia relations that remained tense for more than a half century augurs well not only for the two states but also for the two regions of Central and South Asia. It is going to help curb the rise of extremist forces and terrorism which have posed serious threats to not only regional peace and stability but economic development also particularly since the start of the conflict in Afghanistan which the two regions surround on all sides. If Pakistan and Russia are able to leave behind the legacy of their sour past the potential and opportunities to strengthen their relationship through trade, investment and collaboration in energy and defence sectors are immense. This study aims to analyze the different phases of Pakistan-Russia relations and the dynamics of the current rapprochement if it proceeds without hindrance and their impact on the geo-political and security environment of the region. In the end recommendations are suggested that may facilitate the reset in Pak-Russia ties. Key Words: Pakistan, Russia, Rapprochement, Security and Economic Cooperation. Introduction raditionally, Pak-Russian relations have been marred by two historical developments: (a) Pakistan’s early dependence on the West T led by the United States and (b) the Indo-centric approach adopted by Russia and Pakistan’s response to that policy. The story of Pak-Russian relationship can be described as a tale of misperceptions and lost opportunities.1 Opportunities that political developments offered in the past were missed by both the countries due to their divergent approaches. -

"Disintegration of Pakistan – the Role of Former Union of Soviet Socialist

Syed Waqar Ali Shah1 Shaista Parveen2 “Disintegration of Pakistan – The Role of Former Union of Soviet Socialist Republic (USSR)” An Appraisal Abstract The Pak-USSR relations have a much checkered history. Since independence there is an entanglement in relations of both the countries. Unfortunately, Pakistan tilted from the very beginning towards the West and failed to win the support of the neighboring countries. India, Afghanistan and China were the main countries with whom initially relations were not cordial. The former two countries never improved its relations with Pakistan however, with the direction of USA; Pakistan played a part of facilitator between China and USA. It was not acceptable to USSR, so it never hesitated to pressurize Pakistan for its pro-western policies and joining of security pacts. No doubt that as a super power USSR strengthened its relations with India and used it as a base against the pro- western Pakistan. Joining the western security pacts and its increasing dependence on China were the main causes for the resentment of USSR. That’s why it signed mutual defense and security pact with India to fully equip her against Pakistan. Pakistan also committed blunders in the formulation of its foreign policy and avoid the principle of bilateralism. It could not maintain its non-alignment position which caused serious threats to its security and the result was the dismemberment of East Pakistan with the help of USSR by India, while no western super power supported Pakistan in its war against Indian aggression. Introduction Pakistan – Soviet Union relationship is marked more by the security concerns of each of the two nations than any other factor. -

The Pakistani Lawyers' Movement and the Popular

NOTES THE PAKISTANI LAWYERS’ MOVEMENT AND THE POPULAR CURRENCY OF JUDICIAL POWER “I support the lawyers,” said the Pakistani farmer on the train from Lahore, “because if Musharraf can do whatever he wants to this man, the Chief Justice of Pakistan, then none of us is safe.”1 It was the summer of 2008, and for several months Pakistani lawyers had been leading protests seeking the restoration to office of sixty-plus superior court judges,2 including Chief Justice Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhry, who had been suspended by President Pervez Musharraf.3 The farm- er’s response to questions about his thoughts on the protests was typi- cal of Pakistanis at the time in its clear-headed articulation of the symbolic importance of the lawyers’ struggle and in its implicit under- standing of the central function of an independent judiciary. Indeed, the Chief Justice was the closest to a personal embodiment of “the law” that one could find in Pakistan. If even he served at the pleasure of a dictator — so the story went —the capacity of the law to constrain this dictator and protect ordinary Pakistanis was perilously weak. In March 2007, Chaudhry refused the urging of five generals to re- sign and was removed by Musharraf. Two years later, with Musharraf in exile and a civilian government in power, nationwide protests re- turned Chaudhry to his position atop the nation’s highest court.4 Af- ter twenty-four months of struggle, the lawyers’ movement thus ended with an improbable victory. Moreover, in a nation where the courts historically have followed the dictates of the military and allowed for the repeated subversion of the country’s constitutions,5 the restoration ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 1 Interview with Pakistani farmer, on train from Lahore, Pak. -

Pak-Russia Relations: Lost Opportunities and Future Options

Journal of Political Studies, Vol. 19, Issue - 1, 2012, 79:89 Pak-Russia Relations: Lost Opportunities and Future Options Nazir Hussain♣ Abstract Pak-Russian relations have been marred by historical legacies, over-emphasized western dependence and Pakistan’s Indo- centric approach. There have been many ups and downs in the history of their relations but most of the times they have perceived each other in negative mindset; Pakistan through the prism of western perception and the Soviets/Russia through the Indian eyes. Both countries have strong potential to improve their relations in the fast changing regional and global security environment but it depends how both countries utilize the new opportunities knocking their doors. Russian Federation is reasserting its role in its immediate sphere of influence and beyond, and Pakistan is looking for new avenues of opportunities in the face of US/western standoff. Therefore, both have geopolitical and strategic compulsions to improve their relations. Key Words: Pakistan, Russia, United States, policy, power Going back to the roots and analyzing theoretically, the history of Pak-Russia relations is a tale of misperceptions and lost opportunities. International political history is a western discourse; it is not intended here to go through the delicate discussion of post-modernism, especially of Michael Foucault, and demonstrate that knowledge is a function of the present power. In fact, here, it is just to highlight the obvious lack of rationality in the pursuit of Pakistan’s foreign policy towards Russia. Rationality can simply be defined as a state understands its ‘real’ interests and a ‘sincere’ conduct of its foreign policy in realization of them. -

The Russia-Pakistan Rapprochement: Should India Worry?

NOVEMBER 2015 ISSUE NO. 117 The Russia-Pakistan Rapprochement: Should India Worry? UMA PURUSHOTHAMAN ABSTRACT A rapprochement of sorts seems to be underway between two countries important to India's foreign policy calculusits long-time partner and primary supplier of arms, Russia, and a neighbour with which it has had hostile relations, Pakistan. Beginning with a thaw in the 2000s, the two countries appear to have taken their relationship to the next level with the recent transfer of MI-35 helicopters to Pakistan from Russia. What are the forces driving this new outreach between the two countries? And what are the implications for India? This paper argues that Russia-Pakistan relations are unlikely to develop into a true strategic partnership given India's leverage over Russia, the historical memory of Russia-India ties, and Pakistan's own relations with the US and China. Still, India must remain wary of this new dynamic in Russia-Pakistan ties and tailor its policies accordingly. INTRODUCTION fulfil its energy requirements. Signs of a thaw between Moscow and Islamabad were first In yet another sign of the recent warming of ties publicly noticed in 2009 when the idea of a between them, Russia and Pakistan signed an quadrilateral of Russia, Afghanistan, Tajikistan agreement in October 2015 to build a gas pipeline and Pakistan was floated to increase regional connecting LPG terminals in Lahore to terminals security and economic cooperation. Though the in Karachi. The 1,100-km long pipeline, quadrilateral held three summit meetings, it did scheduled to be completed in 2018, is expected to not take off. -

Social Movements in Pakistan During Authoritarian Regimes

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2021 Struggling Against the Odds: Social Movements in Pakistan During Authoritarian Regimes Sajjad Hussain University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the International Relations Commons Scholar Commons Citation Hussain, Sajjad, "Struggling Against the Odds: Social Movements in Pakistan During Authoritarian Regimes" (2021). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/8795 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Struggling Against the Odds: Social Movements in Pakistan During Authoritarian Regimes by Sajjad Hussain A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government School of Interdisciplinary Global Studies College of Arts and Science University of South Florida Co-Major Professor Bernd Reiter, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor Peter Funke, Ph.D. Rachel May, Ph.D. Earl Conteh-Morgan Date of Approval: March 31, 2021 Keywords: Contentious Politics, Democracy, South Asia, Civil Society Copyright © 2021, Sajjad Hussain Acknowledgements: Alhamdulillah. With an immeasurable sense of gratitude, I want to acknowledge the support of so many people who motivated and inspired me to complete my dissertation. They made this journey rewarding. I’d first like to thank my advisor, Professor Bernd Reiter whose mentorship has been an influential source in shaping my research work. His scholarly encouragement and support throughout these years have been invaluable. -

Pakistan-Russia Relations Redux: from Estrangement to Pragmatism

Pakistan-Russia Relations Redux: Muhammad Nawaz Khan From Estrangement to Pragmatism Muhammad Nawaz Khan* Abstract Pakistan-Russia relations have a complex history of divergences, contradictions and ambiguities that heightened during the Cold War and subsequent era of Afghan Jihad. However, the gradual rapprochement that paved the way for institutionalised engagement started after Pakistan joined the war against terrorism. Based on secondary review of academic and online sources, this article explores how relations between the two countries evolved from estrangement to institutional engagement, with a special focus on why this relationship is significant for both. Economic, energy, defence, counterterrorism, and socio-cultural domains are the important variables that are discussed. Given existing geopolitical compulsions like Moscow‟s quest for playing a decisive role in Afghanistan‟s security calculus; Pakistan‟s pursuit for coming out of the United States‟ straitjacket and finding alternative regional partners offer the reasons, challenges and outlook in shaping prospective ties. It is argued that Pakistan-Russia ties are likely to improve in the future, especially in terms of economic, defence and counterterrorism cooperation. Keywords: Bilateral Relations, Cold War, Defence Cooperation, Counterterrorism, Geopolitics, Regional Fragility. * The author is Research Officer at the Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI), Islamabad, Pakistan. He can be reached at: [email protected]. ________________________________ @2019 by the Islamabad Policy Research Institute. IPRI Journal XIX (1): 56-85. https://doi.org/10.31945/iprij.190103. 56 IPRI JOURNAL WINTER 2019 Pakistan-Russia Relations Redux: From Estrangement to Pragmatism Introduction akistan-Russia relations can be best summarised as a narrative of mutual misunderstandings, miscalculations and wasted opportunities P due to the shifting policies of the two states under geopolitical realities of the Cold War period. -

Pakistan: Ethno-Politics and Contending Elites Discussion Paper No

The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) is an autonomous agency engaging in multi-disciplinary research on the social dimensions of contemporary problems affecting development. Its work is guided by the conviction that, for effective development policies to be formulated, an understanding of the social and political context is crucial. The Institute attempts to provide governments, development agencies, grassroots organizations and scholars with a better understanding of how development policies and processes of economic, social and environmental change affect different social groups. Working through an extensive network of national research centres, UNRISD aims to promote original research and strengthen research capacity in developing countries. Current research programmes include: Business Responsibility for Sustainable Development; Emerging Mass Tourism in the South; Gender, Poverty and Well-Being; Globalization and Citizenship; Grassroots Initiatives and Knowledge Networks for Land Reform in Developing Countries; New Information and Communication Technologies; Public Sector Reform and Crisis-Ridden States; Technical Co-operation and Women’s Lives: Integrating Gender into Development Policy; and Volunteer Action and Local Democracy: A Partnership for a Better Urban Future. Recent research programmes have included: Crisis, Adjustment and Social Change; Culture and Development; Environment, Sustainable Development and Social Change; Ethnic Conflict and Development; Participation and Changes in Property -

Ray of Hope: the Case of Lawyers' Movement in Pakistan

Ray of Hope: The Case of Lawyers’ Movement in Pakistan Azmat Abbas and Saima Jasam A Ray of Hope: The Case of Lawyers’ Movement in Pakistan This piece is an excerpt out of the forthcoming book of Heinrich-Boll-Stiftung (Nov 09) in the publication series on promoting Democracy under Conditions of State Fragility. Pakistan: Reality, Denial and the Complexity of its state. OUTLINE This paper dwells on one of the historic movements, namely the Lawyers‟ Movement in Pakistan. For enhanced clarity and understanding, the paper is divided into five parts respectively. 1. The first part tries to define and touch upon various social, political and non-violent movements around the World and Pakistan. 2. Part two sheds light on Pakistan‟s judicial history. 3. Part three highlights the major associated conflicts. 4. Part four reflects upon state power and the resistance offered to it. 5. Part five a concluding part focuses on the long term implications and hope for the future. References Abbreviations The author’s Profile Azmat Abbas a Masters in Political Science from the University of Punjab, Abbas spent an academic year at the prestigious Stanford University, California, as a John S. Knight Fellow 2004. He has worked at various positions with the print and electronic media for more than 15 years. He has extensively written on religions violence, militancy, terrorism, sectarian conflict and issues of governance in Pakistan. He has also produced an 11-episode documentary series titled "Madressahs or Nurseries of Terror?" in 2008. Saima Jasam is presently working with Heinrich-Boll- Stiftung, Lahore Pakistan as head of the program section.