Will the Long March to Democracy in Pakistan Finally Succeed?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISI in Pakistan's Domestic Politics

ISI in Pakistan’s Domestic Politics: An Assessment Jyoti M. Pathania D WA LAN RFA OR RE F S E T Abstract R U T D The articleN showcases a larger-than-life image of Pakistan’s IntelligenceIE agencies Ehighlighting their role in the domestic politics of Pakistan,S C by understanding the Inter-Service Agencies (ISI), objectives and machinations as well as their domestic political role play. This is primarily carried out by subverting the political system through various means, with the larger aim of ensuring an unchallenged Army rule. In the present times, meddling, muddling and messing in, the domestic affairs of the Pakistani Government falls in their charter of duties, under the rubric of maintenance of national security. Its extra constitutional and extraordinary powers have undoubtedlyCLAWS made it the potent symbol of the ‘Deep State’. V IC ON TO ISI RY H V Introduction THROUG The incessant role of the Pakistan’s intelligence agencies, especially the Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI), in domestic politics is a well-known fact and it continues to increase day by day with regime after regime. An in- depth understanding of the subject entails studying the objectives and machinations, and their role play in the domestic politics. Dr. Jyoti M. Pathania is Senior Fellow at the Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. She is also the Chairman of CLAWS Outreach Programme. 154 CLAWS Journal l Winter 2020 ISI IN PAKISTAN’S DOMESTIC POLITICS ISI is the main branch of the Intelligence agencies, charged with coordinating intelligence among the -

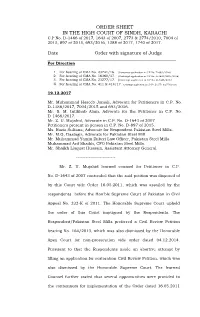

ORDER SHEET in the HIGH COURT of SINDH, KARACHI C.P No

ORDER SHEET IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH, KARACHI C.P No. D-1466 of 2017, 1643 of 2007, 2773 & 2774/2010, 7004 of 2015, 897 of 2015, 693/2016, 1388 of 2017, 1740 of 2017. _________________________________________________________ Date Order with signature of Judge ________________________________________________________ For Direction 1. For hearing of CMA No. 23741/16. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-693/2016) 2. For hearing of CMA No. 16360/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-1643/2007/2016) 3. For hearing of CMA No. 23277/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-1466/2017) 4. For hearing of CMA No. 411 & 414/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-2773 & 2774/2010) 19.12.2017 Mr. Muhammad Haseeb Jamali, Advocate for Petitioners in C.P. No. D-1388/2017, 7004/2015 and 693/2016. Mr. S. M. Intikhab Alam, Advocate for the Petitioner in C.P. No. D-1466/2017. Mr. Z. U. Mujahid, Advocate in C.P. No. D-1643 of 2007 Petitioners present in person in C.P. No. D-897 of 2015. Ms. Razia Sultana, Advocate for Respondent Pakistan Steel Mills. Mr. M.G, Dastagir, Advocate for Pakistan Steel Mill Mr. Muhammad Yamin Zuberi Law Officer, Pakistan Steel Mills. Muhammad Arif Shaikh, CFO Pakistan Steel Mills. Mr. Shaikh Liaquat Hussain, Assistant Attorney General. ------------------------- Mr. Z. U. Mujahid learned counsel for Petitioner in C.P. No. D-1643 of 2007 contended that the said petition was disposed of by this Court vide Order 16.05.2011, which was assailed by the respondents before the Hon’ble Supreme Court of Pakistan in Civil Appeal No. -

Islamabad Long March Declaration”

OFFICIAL TEXT: “Islamabad Long March Declaration” Following decisions were unanimously arrived at; having been taken today, 17 January 2013, in the meeting which was participated by coalition parties delegation led by Chaudry Shujaat Hussain including: 1) Makdoom Amin Fahim, PPP 2) Syed Khursheed Shah, PPPP 3) Qamar ur Zama Qaira, PPPP 4) Farooq H Naik, PPPP 5) Mushahid Hussain, PML-Q 6) Dr Farooq Sattar, MQM 7) Babar Ghauri, MQM 8) Afrasiab Khattak, ANP 9) Senator Abbas Afridi, FATA With the founding leader of Minhaj-ul-Quran International (MQI) and chairman Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT), Dr Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri. The Decisions 1) The National Assembly shall be dissolved at any time before March 16, 2013, (due date), so that the elections may take place within the 90 days. One month will be given for scrutiny of nomination paper for the purpose of pre-clearance of the candidates under article 62 and 63 of the constitution so that the eligibility of the candidates is determined by the Elections Commission of Pakistan. No candidate would be allowed to start the election campaign until pre-clearance on his/her eligibility is given by the Election Commission of Pakistan. 2) The treasury benches in complete consensus with Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT) will propose names of two honest and impartial persons for appointment as Caretaker Prime Minister. 3) Issue of composition of the Election Commission of Pakistan will be discussed at the next meeting on Sunday, January 27, 2013, 12 noon at the Minhaj-ul-Quran Secretariat. Subsequent meetings if any in this regard will also be held at the central secretariat of Minhaj-ul-Quran in Lahore. -

Pakistan, Country Information

Pakistan, Country Information PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Pakistan.htm[10/21/2014 9:56:32 AM] Pakistan, Country Information General 2.1 The Islamic Republic of Pakistan lies in southern Asia, bordered by India to the east and Afghanistan and Iran to the west. -

Pakistan's 2008 Elections

Pakistan’s 2008 Elections: Results and Implications for U.S. Policy name redacted Specialist in South Asian Affairs April 9, 2008 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RL34449 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Pakistan’s 2008 Elections: Results and Implications for U.S. Policy Summary A stable, democratic, prosperous Pakistan actively working to counter Islamist militancy is considered vital to U.S. interests. Pakistan is a key ally in U.S.-led counterterrorism efforts. The history of democracy in Pakistan is a troubled one marked by ongoing tripartite power struggles among presidents, prime ministers, and army chiefs. Military regimes have ruled Pakistan directly for 34 of the country’s 60 years in existence, and most observers agree that Pakistan has no sustained history of effective constitutionalism or parliamentary democracy. In 1999, the democratically elected government of then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif was ousted in a bloodless coup led by then-Army Chief Gen. Pervez Musharraf, who later assumed the title of president. In 2002, Supreme Court-ordered parliamentary elections—identified as flawed by opposition parties and international observers—seated a new civilian government, but it remained weak, and Musharraf retained the position as army chief until his November 2007 retirement. In October 2007, Pakistan’s Electoral College reelected Musharraf to a new five-year term in a controversial vote that many called unconstitutional. The Bush Administration urged restoration of full civilian rule in Islamabad and called for the February 2008 national polls to be free, fair, and transparent. U.S. criticism sharpened after President Musharraf’s November 2007 suspension of the Constitution and imposition of emergency rule (nominally lifted six weeks later), and the December 2007 assassination of former Prime Minister and leading opposition figure Benazir Bhutto. -

KAS International Reports 10/2015

Other Topics 10|2015 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 61 ROLE OR RULE? THE EVOLUTION OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN PAKISTAN 2014 - 2015 Zafar Nawaz Jaspal INTRODUCTION The Pakistanis celebrated the 67th anniversary of their country’s independence amidst immense political bewilderment. The power appeared to be draining away from elected Prime Minister Mian Nawaz Sharif. The celebration marking the anniversary of inde- pendence at the mid-night in front of the Parliament building on 14 August 2014 seemed a regime saving tactic. Notwithstanding, Dr. Zafar Nawaz the smart political move to demonstrate that the Prime Minister Jaspal is the Director of the enjoys complete trust and support of the military, the processes School of Politics for political polarisation has been unleashed in the insecurity- and International ridden country by both Azadi March (freedom movement) led by Relations at the Quaid-I-Azam Uni- cricketer-turned-politician Imran Khan and Inqlab March (revolu- versity Islamabad, tion movement) led by Canada-based Sunni cleric Tahir-ul- Qadri Pakistan. in Lahore on 14 August 2014. The demonstrators demanded the resignation of an elected Premier Sharif and fresh elections in the country. Imran Khan, chairman of Tehreek-i-Insaf,1 ques- tioned the legitimacy of the government by claiming that the 2013 general elections were rigged.2 Khan’s critics opined that he was being manipulated by the Military to try to bring down Premier Sharif or at least check him by questioning his political legitimacy. The accusation of rigging in general elections not only dented the legitimacy of elected government of Premier Nawaz Sharif, but also increased the role of the military in the Pakistani polity. -

Politics and Pirs: the Nature of Sufi Political Engagement in 20Th and 21St Century Pakistan

Ethan Epping Politics and Pirs: The Nature of Sufi Political Engagement in 20th and 21st Century Pakistan By Ethan Epping On November 27th, 2010 a massive convoy set off from Islamabad. Tens of thousands of Muslims rode cars, buses, bicycles, and even walked the 300 kilometer journey to the city of Lahore. The purpose of this march was to draw attention to the recent rash of terrorism in the country, specifically the violent attacks on Sufi shrines throughout Pakistan. In particular, they sought to demonstrate to the government that the current lack of action was unacceptable. “Our caravans will reach Lahore,” declared one prominent organizer, “and when they do the government will see how powerful we are.”1 The Long March to Save Pakistan, as it has come to be known, was an initiative of the recently founded Sunni Ittehad Council (SIC), a growing coalition of Barelvi Muslims. The Barelvi movement is the largest Islamic sect within Pakistan, one that has been heavily influenced by Sufism throughout its history. It is Barelvis whose shrines and other religious institutions have come under assault as of late, both rhetorically and violently. As one might expect, they have taken a tough stance against such attacks: “These anti-state and anti-social elements brought a bad name to Islam and Pakistan,” declared Fazal Karim, the SIC chairman, “we will not remain silent and [we will] defend the prestige of our country.”2 The Long March is but one example of a new wave of Barelvi political activism that has arisen since the early 2000s. -

“Reconciliation” in Pakistan, 2006-2017: a Critical Reappraisal

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan Volume No. 54, Issue No. 2 (July - December 2017) Muhammad Iqbal Chawla ERA OF “RECONCILIATION” IN PAKISTAN, 2006-2017: A CRITICAL REAPPRAISAL Abstract This paper deals with an era of unusual political development which can be described as the „era of reconciliation‟ from 2006 to 2017. This era was unique in Pakistan‟s history because it brought closer all political parties for restoration, protection, and continuation of democracy in Pakistan. However, after a decade this period, sometimes also can be characterized as the era of the Charter of Democracy (COD,) seems to be losing its relevance because of surfacing of anti- democratic forces. Therefore this paper traces the causes, events and the deep impact of the policy of „reconciliation‟ and also touches upon why and how it seems to be coming to an end. As a national leader Benazir Bhutto had political acumen and she propounded the “Philosophy of Reconciliation” after having gone through some bitter political experiences as a Prime Minister and leader of the Opposition. Both Benazir and Mian Nawaz Sharif learnt the lesson when they were sent into their respective exile by General Musharraf. Having learnt their lessons both of them decided upon strengthening the culture of democracy in Pakistan. Benazir not only originated the idea of Reconciliation but also tried to translate her ideas into actions by concluding the „Charter of Democracy‟ (“COD”) with other political parties especially with the Pakistan Muslim League (hereafter “PML (N)”), in 2006”. Introduction Asif Ali Zardari1 as PPP2‟s main leader tried to implement this philosophy after the sudden death of Benazir Buhtto and particularly during his term as President of Pakistan (2008-2013). -

Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (Ppra) Contract Award

ATTACHMENT – I (See regulation 2) PUBLIC PROCUREMENT REGULATORY AUTHORITY (PPRA) CONTRACT AWARD PROFORMA – I To Be Filled And Uploaded on PPRA Website In Respect of All Public Contracts of Works, Services and Goods Worth Fifty Million or More NAME OF THE ORGANIZATION Privatisation Commission__ FEDERAL / PROVINCIAL GOVT. Federal Government_________ TITLE OF CONTRACT Financial Advisory Services Agreement___ TENDER NUMBER TS233834E ______ BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF CONTRACT Divestment of Government of Pakistan shareholding in Pakistan Steel Mills Corporation (PSMC) TENDER VALUE Approx. US$ 3.6 Million______ ENGINEER’S ESTIMATE N/A_________________________ (for civil Works only) ESTIMATED COMPLETION PERIOD December, 2015 WHETHER THE PROCUREMENT WAS INCLUDED IN ANNUAL PROCUREMENT PLAN? _________ N/A _____________Yes / No ADVERTISEMENT : (i) PPRA Website____16-02-2015____ TS233834E _____Yes / No (Federal Agencies) (If yes give date and PPRA’s tender number) (ii) News Papers_Yes (List of Newspapers / Press (Annex – I) Yes / No (If yes give names of newspapers and dates) TENDER OPENED ON (DATE & TIME) _____14-04-2015 (1100 Hrs)____ NATURE OF PURCHASE Local and International _ (Local / International) EXTENSION IN DUE DATE (If any)_____ Yes ____Yes / No -: 2 :- NUMBER OF TENDER DOCUMENTS SOLD 2 (Attach list of Buyers) WHETHER QUALIFICATION CRITERIA WAS INCLUDED IN BIDDING/TENDER DOCUMENTS _Yes__Yes / No (If yes enclose a copy). WHETHER BID EVALUATION CRITERIA WAS INCLUDED IN BIDDING/TENDER DOCUMENTS_ Yes __Yes / No (If yes enclose a copy). -

Political Instability and Lessons for Pakistan: Case Study of 2014 PTI Sit in Protests

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Political Instability and Lessons for Pakistan: Case Study of 2014 PTI Sit in Protests Javed, Rabbia and Mamoon, Dawood University of Management and Technology 7 January 2017 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/76086/ MPRA Paper No. 76086, posted 11 Jan 2017 07:29 UTC Political Instability and Lessons for Pakistan: Case Study of 2014 PTI Sit in/Protests Rabbia Javed University of Management and Technology and Dawood Mamoon University of Management and Technology Abstract: It’s a short allegory to present the case for the importance of Political stability in the economic progress of a country. The Arab spring protests were seen as strengthening democracy in the Arab world. Notwithstanding the surprise Arab spring brought in shape of further destabilizing Middle East, a similar environment of unrest and protests in a practicing democracy like Pakistan capture same dynamics of uncertainty that dampen economic destabilization. The paper briefly covers PTI’s sit in protests in year 2014 to make a case for how political instability stifled economic progress in Pakistan though momentarily. 1. Introduction: The political stability is condition for the nation building and in return it is a process compulsory for the development of a nation. In most of developing countries the governments are not stable. A new government comes into the power overnight; either through coup or army takes over. The new government introduces a new system of rules for the operation of business which cause frustration and anger among the people. Political instability now becomes a serious problem especially in developing countries. -

Tundra Case – Aisha Steel Mills Limited

TUNDRA CASE AISHA STEEL MILLS LIMITED PAKISTAN TUNDRA CASE AISHA STEEL MILLS LIMITED TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION 3 STEEL INDUSTRY IN PAKISTAN 3 RATIONALE FOR TUNDRA’S INVESTMENT 4 REFERENCES 4 COMPANY FACTS AND ENGAGEMENT 5 DISCLAIMER 6 Capital invested in a fund may either increase or decrease in value and it is not certain that you will be able to recover all of your investment. Historical return is no guarantee of future return. The value of invested capital may vary substantially due to the composition of the fund and the investment process used by the fund manager. The Full Prospectus, KIID etc. are available on our homepage. You can also contact us to receive the documents free of charge. See full disclaimer on www.tundrafonder.se 2 TUNDRA CASE AISHA STEEL MILLS LIMITED INTRODUCTION In early 2017, Aisha Steel Mills Limited (ASML) was bought on behalf of three of Tundra Fonder’s funds. The first and only exposure in the steel market in Pakistan, ASML constitutes an interesting case study of a sustainable mid-sized steel company in the country. Factors such as continued economic growth in the country, an increased demand for steel, and regulations promoting domestic manufacturing created a favorable investment environment. The iron and steel sector is one of the most energy-intensive in the world. With a global capacity of just over 1.6bn tonnes (2016), the sector relies heavily on water, energy and labour [1]. Materials needed to make steel include iron ore, coal, limestone and recycled steel. Steel production methods have evolved significantly since the steel industry first began in the late 19th century. -

Muhammad Nawaz Khan & Beenish Altaf Introduction

Pakistan-Russia RapprochementIPRI Journal XIII, and no.Current 1 (Winter Geo-Politics 2013): 125-134 125 PAKISTAN-RUSSIA RAPPROCHEMENT AND CURRENT GEO-POLITICS ∗ Muhammad Nawaz Khan & Beenish Altaf Abstract The trend of improvement seen lately in Pakistan-Russia relations that remained tense for more than a half century augurs well not only for the two states but also for the two regions of Central and South Asia. It is going to help curb the rise of extremist forces and terrorism which have posed serious threats to not only regional peace and stability but economic development also particularly since the start of the conflict in Afghanistan which the two regions surround on all sides. If Pakistan and Russia are able to leave behind the legacy of their sour past the potential and opportunities to strengthen their relationship through trade, investment and collaboration in energy and defence sectors are immense. This study aims to analyze the different phases of Pakistan-Russia relations and the dynamics of the current rapprochement if it proceeds without hindrance and their impact on the geo-political and security environment of the region. In the end recommendations are suggested that may facilitate the reset in Pak-Russia ties. Key Words: Pakistan, Russia, Rapprochement, Security and Economic Cooperation. Introduction raditionally, Pak-Russian relations have been marred by two historical developments: (a) Pakistan’s early dependence on the West T led by the United States and (b) the Indo-centric approach adopted by Russia and Pakistan’s response to that policy. The story of Pak-Russian relationship can be described as a tale of misperceptions and lost opportunities.1 Opportunities that political developments offered in the past were missed by both the countries due to their divergent approaches.