Social Movements in Pakistan During Authoritarian Regimes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 124, folder “Pakistan” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 124 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library MEMORANDUM THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON January 10, 1975 MEMORANDUM FOR: RON NESSEN FROM: LESJANKA SUBJECT: Morning Press Items IT EMS TO BE ANNOUNCED OR VOLUNTEERED: 1. Announcement of Bhutto Visit: 11The President has invited the Prime Minister of Pakistan Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Begum Nusrat Bhutto to Washington for an Official Visit February 4-7. The Prime Minister will meet with President Ford on February 5 and with other high level officials during his visit. The President and Mrs. Ford will host a dinner at the White House in honor of the Prime Minister and Begum Nusrat Bhutto on the evening of February 5. Secretary Kissinger conveyed this invitation to Prime Minister Bhutto during his visit to Pakistan October 31 - November 1, 1974. -

India-Pakistan Conflict: Records of the Us State Department, February 1963

http://gdc.gale.com/archivesunbound/ INDIA-PAKISTAN CONFLICT: RECORDS OF THE U.S. STATE DEPARTMENT, FEBRUARY 1963-1966 Over 16,000 pages of State Department Central Files on India and Pakistan from 1963 through 1966 make this collection a standard documentary resource for the study of the political relations between India and Pakistan during a crucial period in the Cold War and the shifting alliances and alignments in South Asia. Date Range: 1963-1966 Content: 15,387 images Source Library: U.S. National Archives Detailed Description: Relations with Pakistan have demanded a high proportion of India’s international energies and undoubtedly will continue to do so. India and Pakistan have divergent national ideologies and have been unable to establish a mutually acceptable power equation in South Asia. The national ideologies of pluralism, democracy, and secularism for India and of Islam for Pakistan grew out of the pre-independence struggle between the Congress and the All-India Muslim League, and in the early 1990s the line between domestic and foreign politics in India’s relations with Pakistan remained blurred. Because great-power competition—between the United States and the Soviet Union and between the Soviet Union and China—became intertwined with the conflicts between India and Pakistan, India was unable to attain its goal of insulating South Asia from global rivalries. This superpower involvement enabled Pakistan to use external force in the face of India’s superior endowments of population and resources. The most difficult problem in relations between India and Pakistan since partition in August 1947 has been their dispute over Kashmir. -

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE the COLONIAL CONTEXT: the BIRTH of BANGLADESH in Retrospectt

SELF-DETERMINATION OUTSIDE THE COLONIAL CONTEXT: THE BIRTH OF BANGLADESH IN RETROSPECTt By VedP. Nanda* I. INTRODUCTION In the aftermath of the Indo-Pakistan War in December 1971, the independent nation-state of Bangladesh was born.' Within the next four months, more than fifty countries had formally recognized the new nation.2 As India's military intervention was primarily responsible for the success of the secessionist movement in what was then known as East Pakistan, and for the creation of a new political entity on the inter- national scene,3 many serious questions stemming from this historic event remain unresolved for the international lawyer. For example: (1) What is the continuing validity of Article 2 (4) of the United Nations Charter?4 (2) What is the current status of the doctrine of humanita- rian intervention in international law?5 (3) What action could the United Nations have taken to avert the Bangladesh crisis?6 (4) What measures are necessary to prevent such tragic occurrences in the fu- ture?7 and (5) What relationship exists between the principle of self- "- This paper is an adapted version of a chapter that will appear in Y. ALEXANDER & R. FRIEDLANDER, SELF-DETERMINATION (1979). * Professor of Law and Director of the International Legal Studies Program, Univer- sity of Denver Law Center. 1. See generally BANGLADESH: CRISIS AND CONSEQUENCES (New Delhi: Deen Dayal Research Institute 1972); D. MANKEKAR, PAKISTAN CUT TO SIZE (1972); PAKISTAN POLITI- CAL SYSTEM IN CRISIS: EMERGENCE OF BANGLADESH (S. Varma & V. Narain eds. 1972). 2. Ebb Tide, THE ECONOMIST, April 8, 1972, at 47. -

Pakistan: Arrival and Departure

01-2180-2 CH 01:0545-1 10/13/11 10:47 AM Page 1 stephen p. cohen 1 Pakistan: Arrival and Departure How did Pakistan arrive at its present juncture? Pakistan was originally intended by its great leader, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, to transform the lives of British Indian Muslims by providing them a homeland sheltered from Hindu oppression. It did so for some, although they amounted to less than half of the Indian subcontinent’s total number of Muslims. The north Indian Muslim middle class that spearheaded the Pakistan movement found itself united with many Muslims who had been less than enthusiastic about forming Pak- istan, and some were hostile to the idea of an explicitly Islamic state. Pakistan was created on August 14, 1947, but in a decade self-styled field marshal Ayub Khan had replaced its shaky democratic political order with military-guided democracy, a market-oriented economy, and little effective investment in welfare or education. The Ayub experiment faltered, in part because of an unsuccessful war with India in 1965, and Ayub was replaced by another general, Yahya Khan, who could not manage the growing chaos. East Pakistan went into revolt, and with India’s assistance, the old Pakistan was bro- ken up with the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. The second attempt to transform Pakistan was short-lived. It was led by the charismatic Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who simultaneously tried to gain control over the military, diversify Pakistan’s foreign and security policy, build a nuclear weapon, and introduce an economic order based on both Islam and socialism. -

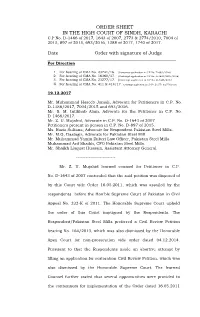

ORDER SHEET in the HIGH COURT of SINDH, KARACHI C.P No

ORDER SHEET IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH, KARACHI C.P No. D-1466 of 2017, 1643 of 2007, 2773 & 2774/2010, 7004 of 2015, 897 of 2015, 693/2016, 1388 of 2017, 1740 of 2017. _________________________________________________________ Date Order with signature of Judge ________________________________________________________ For Direction 1. For hearing of CMA No. 23741/16. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-693/2016) 2. For hearing of CMA No. 16360/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-1643/2007/2016) 3. For hearing of CMA No. 23277/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-1466/2017) 4. For hearing of CMA No. 411 & 414/17. (Contempt application in C.P No. D-2773 & 2774/2010) 19.12.2017 Mr. Muhammad Haseeb Jamali, Advocate for Petitioners in C.P. No. D-1388/2017, 7004/2015 and 693/2016. Mr. S. M. Intikhab Alam, Advocate for the Petitioner in C.P. No. D-1466/2017. Mr. Z. U. Mujahid, Advocate in C.P. No. D-1643 of 2007 Petitioners present in person in C.P. No. D-897 of 2015. Ms. Razia Sultana, Advocate for Respondent Pakistan Steel Mills. Mr. M.G, Dastagir, Advocate for Pakistan Steel Mill Mr. Muhammad Yamin Zuberi Law Officer, Pakistan Steel Mills. Muhammad Arif Shaikh, CFO Pakistan Steel Mills. Mr. Shaikh Liaquat Hussain, Assistant Attorney General. ------------------------- Mr. Z. U. Mujahid learned counsel for Petitioner in C.P. No. D-1643 of 2007 contended that the said petition was disposed of by this Court vide Order 16.05.2011, which was assailed by the respondents before the Hon’ble Supreme Court of Pakistan in Civil Appeal No. -

Islamabad Long March Declaration”

OFFICIAL TEXT: “Islamabad Long March Declaration” Following decisions were unanimously arrived at; having been taken today, 17 January 2013, in the meeting which was participated by coalition parties delegation led by Chaudry Shujaat Hussain including: 1) Makdoom Amin Fahim, PPP 2) Syed Khursheed Shah, PPPP 3) Qamar ur Zama Qaira, PPPP 4) Farooq H Naik, PPPP 5) Mushahid Hussain, PML-Q 6) Dr Farooq Sattar, MQM 7) Babar Ghauri, MQM 8) Afrasiab Khattak, ANP 9) Senator Abbas Afridi, FATA With the founding leader of Minhaj-ul-Quran International (MQI) and chairman Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT), Dr Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri. The Decisions 1) The National Assembly shall be dissolved at any time before March 16, 2013, (due date), so that the elections may take place within the 90 days. One month will be given for scrutiny of nomination paper for the purpose of pre-clearance of the candidates under article 62 and 63 of the constitution so that the eligibility of the candidates is determined by the Elections Commission of Pakistan. No candidate would be allowed to start the election campaign until pre-clearance on his/her eligibility is given by the Election Commission of Pakistan. 2) The treasury benches in complete consensus with Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT) will propose names of two honest and impartial persons for appointment as Caretaker Prime Minister. 3) Issue of composition of the Election Commission of Pakistan will be discussed at the next meeting on Sunday, January 27, 2013, 12 noon at the Minhaj-ul-Quran Secretariat. Subsequent meetings if any in this regard will also be held at the central secretariat of Minhaj-ul-Quran in Lahore. -

Pakistan, Country Information

Pakistan, Country Information PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Pakistan.htm[10/21/2014 9:56:32 AM] Pakistan, Country Information General 2.1 The Islamic Republic of Pakistan lies in southern Asia, bordered by India to the east and Afghanistan and Iran to the west. -

1. Syed Khalid Siraj Subhani 2. Mian Asad Hayaud

PROFILE OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE FILED THEIR INTENTION TO OFFER THEMSELVES TO CONTEST IN THE ELECTION OF DIRECTORS AT THE 11th EXTRAORDINARY GENERAL MEETING SCHEDULED TO BE HELD ON MARCH 17, 2021. 1. Syed Khalid Siraj Subhani Mr. Subhani is a Chemical Engineer with Executive Management Program from Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley and Leadership program from MIT, Boston. A seasoned executive, his career spanned over 33 years with Exxon Chemical Pakistan Limited, which subsequently became Engro Chemical Pakistan Limited and later Engro Corporation Limited. This included long term assignments with Esso Chemical Canada in Edmonton and at ICI site in Billingham UK. Over the years, he worked in numerous senior executive positions at Engro and played instrumental role in growth and diversification of the company to make it one of the largest business conglomerates of Pakistan. Prior to retirement from Engro he worked as President and Chief Executive Officer of Engro Corporation Limited, Engro Fertilisers Limited and Engro Polymer and Chemicals Limited. Mr. Subhani also served as President and Chief Executive Officer of ThalNova Power Thar Private Limited for a period of two years. Earlier Mr. Subhani also served on the board of Engro Corporation Limited (Director), Hub Power Company Limited (Director), Engro Foods Limited (Director), Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company Limited (Director), Laraib Energy Limited (Director), Engro Fertilisers Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Polymer and Chemicals Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Vopak Terminal Limited (Board Chairman), Thar Power Company Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Powergen Qadirpur Limited (Board Chairman), Engro Elengy Terminal (Private) Limited (Board Chairman) and Engro Eximp Agri Products (Private) Limited (Board Chairman). -

Pakistani Politics 1243 Pakistani Politics the Lesson of Gramdan 1244 ERSONALITIES Count in the Politics of Every Country

(Established January 1949) September 28, 1957 Volume IX—No, 39 Price 50 Naye Paise EDITORIALS Pakistani Politics 1243 Pakistani Politics The Lesson of Gramdan 1244 ERSONALITIES count in the politics of every country. But in WEEKLY NOTES P Pakistan, politics seem to centre mainly around personalities. Thin Kandla Nearing Capacity- explains the frequent changes in party tactics and the policies of parties. Reassessment Necessary In such circumstances, as is only to be expected, political stability eludes —Pibul Goes — Welcome the country. It is tempting to draw a parallel between Pakistan and Rapprochement — P r o- Prance. There are some similarities in the underlying conditions in blem of Housing—Scarcity Pakistan and Indonesia. But there are limits beyond which such com of Material — U P's Tax parisons are misleading. Even as President Soekarno experiments with on Large Holdings Bank "guided democracy", President Iskander Mirza talks about "controlled Rate Change and India- democracy". But the Indonesian President's policy is based on an ideal Production of Radio Re whereas the Pakistani President's interference with the affairs of the ceivers 1247 State is solely justified on considerations of that country's integrity. LETTER TO THE EDITOR That also is the main, if not the only, binding force among parties and Chair-borne Critics 1250 politicians in Pakistan. A CALCUTTA DIARY Yet, experience and developing events make it increasingly evident Not by the Police Alone 1251 that Pakistan's march to progress cannot be ensured on such negative foundations as the country's integrity, annexation of Kashmir and the FROM THE LONDON END ever-present problem of maintaining a precarious balance between the Seven Per Cent and the country's two wings. -

Students, Space, and the State in East Pakistan/Bangladesh 1952-1990

1 BEYOND LIBERATION: STUDENTS, SPACE, AND THE STATE IN EAST PAKISTAN/BANGLADESH 1952-1990 A dissertation presented by Samantha M. R. Christiansen to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts September, 2012 2 BEYOND LIBERATION: STUDENTS, SPACE, AND THE STATE IN EAST PAKISTAN/BANGLADESH 1952-1990 by Samantha M. R. Christiansen ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate School of Northeastern University September, 2012 3 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the history of East Pakistan/Bangladesh’s student movements in the postcolonial period. The principal argument is that the major student mobilizations of Dhaka University are evidence of an active student engagement with shared symbols and rituals across time and that the campus space itself has served as the linchpin of this movement culture. The category of “student” developed into a distinct political class that was deeply tied to a concept of local place in the campus; however, the idea of “student” as a collective identity also provided a means of ideological engagement with a globally imagined community of “students.” Thus, this manuscript examines the case study of student mobilizations at Dhaka University in various geographic scales, demonstrating the levels of local, national and global as complementary and interdependent components of social movement culture. The project contributes to understandings of Pakistan and Bangladesh’s political and social history in the united and divided period, as well as provides a platform for analyzing the historical relationship between social movements and geography that is informative to a wide range of disciplines. -

India-Pakistan Conflicts – Brief Timeline

India-Pakistan Conflicts – Brief timeline Added to the above list, are Siachin glacier dispute (1984 beginning – 2003 ceasefire agreement), 2016- 17 Uri, Pathankot terror attacks, Balakot surginal strikes by India Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 The war, also called the First Kashmir War, started in October 1947 when Pakistan feared that the Maharaja of the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu would accede to India. Following partition, princely states were left to choose whether to join India or Pakistan or to remain independent. Jammu and Kashmir, the largest of the princely states, had a majority Muslim population and significant fraction of Hindu population, all ruled by the Hindu Maharaja Hari Singh. Tribal Islamic forces with support from the army of Pakistan attacked and occupied parts of the princely state forcing the Maharaja Pragnya IAS Academy +91 9880487071 www.pragnyaias.com Delhi, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Tirupati & Pune +91 9880486671 www.upsccivilservices.com to sign the Instrument of Accession of the princely state to the Dominion of India to receive Indian military aid. The UN Security Council passed Resolution 47 on 22 April 1948. The fronts solidified gradually along what came to be known as the Line of Control. A formal cease-fire was declared at 23:59 on the night of 1 January 1949. India gained control of about two-thirds of the state (Kashmir valley, Jammu and Ladakh) whereas Pakistan gained roughly a third of Kashmir (Azad Kashmir, and Gilgit–Baltistan). The Pakistan controlled areas are collectively referred to as Pakistan administered Kashmir. Pragnya IAS Academy +91 9880487071 www.pragnyaias.com Delhi, Hyderabad, Bangalore, Tirupati & Pune +91 9880486671 www.upsccivilservices.com Indo-Pakistani War of 1965: This war started following Pakistan's Operation Gibraltar, which was designed to infiltrate forces into Jammu and Kashmir to precipitate an insurgency against rule by India.