Public Diplomacy: a Justification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sourcebook with Marie's Help

AIB Global Broadcasting Sourcebook THE WORLDWIDE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DIRECTORY | TV | RADIO | CABLE | SATELLITE | IPTV | MOBILE | 2009-10 EDITION WELCOME | SOURCEBOOK AIB Global WELCOME Broadcasting Sourcebook THE WORLDWIDE ELECTRONIC MEDIA DIRECTORY | TV | RADIO | CABLE | SATELLITE | IPTV | MOBILE | 2009 EDITION In the people-centric world of broadcasting, accurate information is one of the pillars that the industry is built on. Information on the information providers themselves – broadcasters as well as the myriad other delivery platforms – is to a certain extent available in the public domain. But it is disparate, not necessarily correct or complete, and the context is missing. The AIB Global Broadcasting Sourcebook fills this gap by providing an intelligent framework based on expert research. It is a tool that gets you quickly to what you are looking for. This media directory builds on the AIB's heritage of more than 16 years of close involvement in international broadcasting. As the global knowledge The Global Broadcasting MIDDLE EAST/AFRICA network on the international broadcasting Sourcebook is the Richie Ebrahim directory of T +971 4 391 4718 industry, the AIB has over the years international TV and M +971 50 849 0169 developed an extensive contacts database radio broadcasters, E [email protected] together with leading EUROPE and is regarded as a unique centre of cable, satellite, IPTV information on TV, radio and emerging and mobile operators, Emmanuel researched by AIB, the Archambeaud platforms. We are in constant contact -

External Services on Medium Wave

British DX Club External Services of the World on Mediumwave includes schedules and information, and a frequency order list of external services May 2021 DX Guide External Services of the World on Mediumwave Contents updated: 12 May 2021 2 Introduction 3-30 External services on mediumwave by continent and country: 3-7 Europe 8-12 Africa 13-17 Middle East, East Mediterranean and the Caucasus 17-26 Asia 27-29 Americas 30-57 Frequency order list of external services on mediumwave Introduction This is a guide to external services broadcasting on mediumwave in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Caucasus, Asia and the Americas. It is compiled with the intention of highlighting some of the more interesting services and programmes for the DXer and mediumwave listener. Many external services originate from high-power transmitters and offer a good opportunity to hear and identify more distant stations on mediumwave, especially as the use of clear ID's and familiar interval signal tunes often makes it easier to pick them out on a crowded channel. This guide will be regularly updated and more will be added in future. If you have any corrections, additions, comments or suggestions that will help inprove things, then they are more than welcome. There may be some unintentional errors that have crept in whilst compiling this first edition, so any help in getting these put right would also be greatly appreciated. Please send details to Tony Rogers by email at [email protected]. ______________________________________________________________________________________ 2 Europe Bosnia and Hercegovina Bosnia and Hercegovina - Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (Balkan Service) RFE/RL's Balkan Service in Bosnian is relayed by Radio 1503 Zavidovići, a partner of RFE/RL, daily at 0000, 0800, 1500, 1800 and 2200 local time, according the the RFE/RL website. -

THE ARRIVAL of RADIO FARDA: INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING to IRAN at a CROSSROADS by Hansjoerg Biener*

THE ARRIVAL OF RADIO FARDA: INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING TO IRAN AT A CROSSROADS by Hansjoerg Biener* Abstract: On December 19, 2002, Radio Farda, the new U.S. external service in Persian, officially started regular broadcasts on shortwave, mediumwave and satellite. With the reformatting of existing services into a 24-hour news and entertainment channel, external broadcasting to Iran has recently received more attention. Iran, however, has always been the target area of various international broadcasting services.(1) In its first worldwide press-freedom index published on October 23, 2002, Reporters Without Borders ranked Iran 122nd among 139 countries surveyed.(2) So, the need for independent reporting seems obvious, while some question the need for embedding news and information in a music and entertainment format. This article examines the question in the broader context of international broadcasting to Iran, including clandestine and even religious stations. CLASSIC EXTERNAL resumed operation. The service almost BROADCASTING exclusively drew on native speakers Having been a major political factor some of whom had broadcasting both under Shah Reza Pahlavi and under experience in Iranian radio and Mullah rule, Iran has been a traditional television before 1979. In the 1980s, target area for official external services long before the arrival of e-mail, the both from neighboring countries like Farsi service received several hundred Iraq, Kuwait, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and letters per week in response to the Turkey, as well as the world’s broadcasts.(3) On October 17, 1996, superpowers. In the framework of Voice of America and Worldnet centralized USSR external broadcasting, launched a weekly, call-in radio and TV Radio Baku of the Soviet Republic simulcast in Farsi, the first regularly Azerbaijan only had a minor role as an recurring program to be produced in full external broadcaster, which did however at the VoA headquarters. -

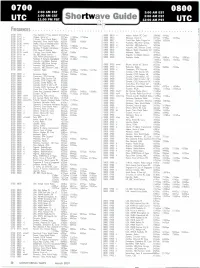

Shortwave Guide 12:00 AM PST UTC

0700 2:00 AM EST 3:00 AM EST 0800 1:00 AM CST 2:00 AM CST UTC 11:00 PM PST Shortwave Guide 12:00 AM PST UTC FREQUENCIES 07000705 New Zealand, R New Zeolond Intl 7675po 08000810 vl Molowi, Malawi BC Corp 3380do 5995do 07000715 Greece, Voice of 9375eu 11900ou 17520me 08000825 Malaysia, Voice of 6275as 9750os 15295os 07000720 0 S Africa, Trans World Radio 7200of 9500af 08000827 Czech Rep, Radio Prague Intl 11600eu 15255eu 07000720 Swaziland, Trans World Radio 6035of 7200af 9500af 08000830 vl Australia, ABC/Alice Springs 4835do 07000730mtwhfa Molto, Voice of Mediterranean 6010eu 07000730 vl Papua New Guinea, NBC 9675do 11880do 08000830 vl Austrolio,ABC/Katherine 5025do 07000730 Slovakia, R Slovakia International 15460ou17550ou 21705ou 08000830 vl Australia, ABC/Tennant Creek 4910do 07000730 USA, Voice of Americo 6873vo 08000830 Belgium, Radio Vlaanderen Intl 5985eu 07000735mtwhf S Africa, Trans World Radio 60350f 9500af 08000830 Myanmar, Radio 9730do 07000745os UK, BBC World Service 17885of 08000900 Anguilla, Caribbean Beacon 60900m 07000745 USA, WYFR Okeechobee FL 7355eu 9985eu 11850eu 08000900 Australia, Radio 5995po 9580vo 9710as 12080pa 07000756 Romania, R Romania International 17720of 21480af 13605vo15240va 15415os17750as 07000800 Anguilla, Caribbean Beacon 6090om 21725va 07000800 vl Australia, ABC/Alice Springs 4835do 08000900mtwhf Bhutan, Bhutan BC Service 07000800 vl Australia,ABC/Katherine 5025do 6035do 07000800 vl Australia, ABC/Tennant Creek 4910do 08000900 vl Botswana, Radio 7255do 9600do 7255do 07000800 Austrolio, Radio 9660po -

L'avenir De La Radiodiffusion Internationale

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCLouvain: Open Journal Repository (Université catholique de Louvain) L’AVENIR DE LA RADIODIFFUSION INTERNATIONALE Bernard Wuilleme1 La question de l’avenir de la radiodiffusion internationale, pour ne pas dire de sa survie, cette question est posée depuis la Chute du Mur de Berlin le 9 novembre 1989, même si cette date est symbolique. En effet, depuis sa naissance depuis les années 1930, la radiodiffu- sion internationale n’a cessé d’avoir un rôle paradoxal. Si sa création a des motifs bien précis : informer ses ressortissants à l’étranger de ce qui se passe en métropole, la réalité deviendra rapi- dement très différente pour devenir un outil de propagande aux mains des Etats. Car faut-il le rappeler : la radiodiffusion internationale est une radio fi nancée, dirigée (ses directeurs sont nommés par le gouver- nement du pays) par les États. Bref rappel de cette « histoire de la radiodiffusion internatio- nale » : – 1930-1939 : Période d’avant-guerre où les forces de l’Axe s’in- téressent aux publics récepteurs des pays colonisés ou sous mandat pour les convaincre de se rebeller contre la métropole. Bien entendu contre-propagande des États colonisateurs sur les mêmes publics. 1 Professeur en Sciences de l’Information et de la Communication Université Jean Moulin Lyon 3 Recherches en communication, n° 26 (2006). 184 BERNARD WUILLEME – 1939-1945 : Véritable « guerre des ondes » entre d’une part les Alliés (Grande-Bretagne, France, États-Unis, Hollande, Belgique, etc) qui contre carrent les actions de propagande, de désinformation, d’intoxication des forces ennemies (Allemagne, Italie, Japon). -

WRTH B18 Schedules Update

This file is a supplement to the 2019 edition of World Radio TV Handbook. It summarises the changes to the B18 schedules printed in the book. Contact details and other information about the stations shown in this file can be found in the International Radio section of WRTH 2019. If you haven’t yet got your copy, the book can be ordered from your nearest bookstore or directly from our website at www.wrth.com/_shop WRTH B18 SCHEDULE UPDATES - FEBRUARY 2019 INTERNATIONAL RADIO B18 BROADCAST SCHEDULES UPDATE (FEBRUARY 2019) Notes for using this update: AUSTRIA (AUT) Schedule additions, deletions, frequency changes and other updates, are shown in paren - TWR EUROPE AND CAMENA (Rlg) theses () at the end of the relevant line. + P.O. Box 12, 82002 Bratislava, Slovakia (HQ). New Dutch address: Schedule additions are shown as (add) , whilst Stichting Trans World Radio Europe, P.O.Box 371, 3770 AJ Barneveld, schedule deletions are shown as (del) . Netherlands. Frequency changes or other updates are Polish Days Area kHz detailed in black italics. Changes to broadcast times are shown in black 2045-2115 mtwtf.. Eu 1467rou (ex mtwtf.s) italics underneath the existing time. BELARUS (BLR) New broadcaster/station entries are shown entirely in green . RADIO BELARUS INTERNATIONAL (Gov) Changes since the previous file release (if any) W: www.r adiobelarus.by are marked in blue italics . French Days Area kHz ALASKA (ALS) 2030-2050 daily CEu,WEu 3985kll (add) Spanish Days Area kHz KNLS INTERNATIONAL (Rlg) 2050-2110 daily CEu,WEu 3985kll (add) Chinese Days Area kHz CAMEROON (CME) 0800-1000 daily EAs 9610nls (ex 7355) 1000-1100 daily EAs 9605nls (ex 7355) SAWTU LINJIILA (VOICE OF THE GOSPEL) (Rlg) 1100-1200 daily EAs 11610nls (ex 7355) Revised Complete Schedule 1300-1600 daily EAs 11890nls (ex 7560) Fulfulde Days Area kHz 1300-1400 daily EAs 11785nls (ex 7320) 1830-1900 mtwt.. -

Burl Edward "B. E." Davis Papers, 1936-1989

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Center for Restoration Studies Archives, Manuscripts and Personal Papers Finding Aids Finding Aids 11-9-2018 Burl Edward "B. E." Davis Papers, 1936-1989 Burl Edward Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/findingaids Preferred Citation [identification of item], [file or folder name], Burldwar E d Davis Papers, 1936-1989. Center for Restoration Studies MS #450. Abilene Christian University Special Collections and Archives, Brown Library. Abilene Christian University, Abilene, TX. This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Restoration Studies Archives, Manuscripts and Personal Papers Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. Burl Edward “B. E.” Davis Papers, (1936-1989) Center for Restoration Studies Manuscripts #450 Abilene Christian University Special Collections and Archives Brown Library Abilene Christian University Abilene, TX 79699-9208 21 January 2021 About this collection Title: Burl Edward “B. E.” Davis Papers Creator: Burl Edward Davis Identifier/Call Number: Center for Restoration Studies Manuscripts #450 Physical Description: 48 linear feet (48 boxes) Dates (Inclusive): 1936-1989 Dates (Bulk): 1965-1989 Location: Center for Restoration Studies Language of Materials: English Scope and Content Note: This collection includes term papers, research reports, journal articles, surveys, correspondence, pamphlets, and presentations. Biographical Note: Burl Edward “B. E.” Davis was a professor of Communication at Abilene Christian University from 1969. Burl Edward Davis married Frances Dawn Bartlett Davis on February 22, 1952. The couple had four children, Kathy, Kay, Phyllis, and Mike. -

BDXC Communication

ISSN 0958-2142 COMMUNICATION MONTHLY JOURNAL OF THE BRITISH DX CLUB SEPTEMBER 2018 EDITION 526 EDITOR CHRISSY BRAND [email protected] TREASURER DAVE KENNY [email protected] SECRETARY ANDREW TETT [email protected] PRINTING ALAN PENNINGTON [email protected] SOCIAL MEDIA STEPHEN HOWIE [email protected] BDXC WEB SITE: www.bdxc.org.uk BDXC FACEBOOK PAGE https://www.facebook.com/BDXCUK/ Contents 2-3 News from HQ 18-19 Radio Veritas 32-33 Beyond the Horizon 4-6 Open to Discussion 20-21 KDKA far north 33 Propagation 6-7 Oldrich Cip 22-23 QSL Report 34-36 MW Logbook 8-11 Listening Post 24-25 UK News 37-38 Tropical Logbook 12-13 Antenna testing 26 Webwatch 39-46 HF Logbook 14-15 My ideal world band radio 27-28 Mediumwave Report 47-50 Alternative Airwaves 16-17 S European Report 28-31 DX News 51 Contributors News From H.Q. Welcome to the September issue . This month's highlights include club member Peter Jones' visit to the now abandoned BBC World Service relay station in the Seychelles, Alan Roe listening to a great range of programmes including Radio Japan's haiku. David Harris looks at features on world band radios and Alexander Beryozkin puts three SW/MW aerials to the test. Put those together with all the latest DX and other radio news, your views plus members' regular QSL reports, AM and FM logs a nd you can see why Communication and the BDXC continue to thrive after 44 years! The BDXC Audio Circle is on hold at present as there aren't enough contributions to make a programme. -

The Listener TWR to South Africa? by C

The Listener TWR to South Africa? By C. M. Stanbury II IN THIS issue, El reports on Africa's cur- ate in the red. Bonneville also owns WRFM. rent hot spots. One item falling into this Under Good Family Stations ownership, category is Trans World Radio's announce- WNYW will no longer accept commercial ment that its newest high -power relay will be programming of any kind and it plans- built in the Republic of South Africa. The when current contractual obligations have ex- Pretoria government never before has al- pired-to adopt an entirely religious format. lowed a privately owned broadcast station to Radio New York has had a varied, and at operate from its territory. One wonders what times mysterious, history. Many people in service TWR has performed in the past, or broadcasting circles have believed for years promised for the future, to rate such a con- that the station was owned and operated by cession. the CIA. This was not the case, however, as Meanwhile, Trans World Radio's 500 -kw WRUL was never actually involved in secret medium -wave transmitter on the island of radio operations. During and immediately Bonaire continues to act as a relay for Radio after the Cuban crisis, the station did carry Nederland. Radio Nederland's world radio programs beamed to Latin America which service is broadcast on 800 kc from 1800 were sponsored by CIA -backed refugee until 1930 EST followed by TWR's religious groups, but this was as close as the station programming. At times this outlet can be actually got to CIA control. -

Contrôle Comprobación Técnica International Des International Monitoring Internacional De Las Emisiones Émissions

UIT - BUREAU DES ITU - UIT - OFICINA DE RADIOCOMMUNICATIONS RADIOCOMMUNICATION RADIOCOMUNICACIONES BUREAU CONTRÔLE COMPROBACIÓN TÉCNICA INTERNATIONAL DES INTERNATIONAL MONITORING INTERNACIONAL DE LAS EMISIONES ÉMISSIONS Cette publication contient les résultats de contrôle This publication contains spectrum Esta publicación contiene la información sobre comprobación des émissions soumis par les administrations monitoring information submitted by técnica de emisiones (CTE) presentada por las conformément à la lettre circulaire du BR CR/159 administrations in accordance with BR administraciones de acuerdo con la carta circular CR/159 de du 9 mai 2001 circular letter CR/159 of 9 May 2001 la BR del 9 de mayo 2001 RÉSUMÉ No: Dernière mise à jour des données: Période : SUMMARY No: 317 Date of last update: 21-01-2009 Monitoring Period: 01-01-08 - 31-03-08 o Ultima fecha de actualización de datos: RESUMEN N : Período : Colonne description Column description Descripción de columna Col. Rubrique Description Col. Item Description Col. Elemento Descripcion 1 M_ADM Administration responsable du centre de 1 M_ADM Administration code responsible for the monitoring 1 M_ADM Administración encargada del centro de contrôle des émissions centre comprobación 2 M_CENTER Centre de contrôle des émissions où les 2 M_CENTER Monitoring centre where the observation was 2 M_CENTER Centro de comprobación en el que se realizó la observations ont été faites made. observación 3 M_FREQ Fréquence mesurée en kHz 3 M_FREQ Frequency measured in kilohertz 3 M_FREQ Frecuencia -

Report 2012-2013

Panorama radiofonico internazionale n. 22 Dal 1982 dalla parte del Radioascolto Report 2012-2013 Rivista telematica edita in proprio dall'AIR Associazione Italiana Radioascolto c.p. 1338 - 10100 Torino AD www.air-radio.it l’editoriale ………………. radiorama PANORAMA RADIOFONICO INTERNAZIONALE organo ufficiale dell’A.I.R. Associazione Italiana Radioascolto Numero ormai storico quello del radiorama report che recapito editoriale: raccoglie tutti i vostri ascolti raccolti durante tutto un anno. radiorama - C. P. 1338 - 10100 TORINO AD e-mail: [email protected] AIR - radiorama Tantissime segnalazioni d’ascolto come sempre completati dagli - Responsabile Organo Ufficiale: Giancarlo VENTURI indirizzi delle emittenti e da brevi note informative sulle stazioni di - Responsabile impaginazione radiorama:Claudio RE - Responsabile Blog AIR-radiorama: i singoli Autori tempo e frequenza campione, su che cosa è l’ora GMT/UTC, che cosa - Responsabile sito web: Emanuele PELICIOLI ------------------------------------------------- sono i buoni di risposta internazionale ed alcuni link utili sulle principali Il presente numero di radiorama e' guide e organizzazioni che si occupano di radioascolto. pubblicato in rete in proprio dall'AIR Associazione Italiana Radioascolto, tramite il server Aruba con sede in località Per poi concludere con le ultime notizie dal mondo ed i Palazzetto, 4 - 52011 Bibbiena Stazione (AR). Non costituisce testata giornalistica, regolamenti per ottenere i diplomi AIR e dedicati al radioascolto. Da non ha carattere periodico ed è aggiornato segnalare inoltre la nuova chiavetta USB personalizzata AIR per avere secondo la disponibilità e la reperibilità dei sempre a portata di mano tutti i numeri di radiorama disponibili in materiali. Pertanto, non può essere considerato in alcun modo un prodotto formato elettronico e le informazioni fin qui raccolte! editoriale ai sensi della L. -

New Zealand DX Times Monthly Journal of the D X New Zealand Radio DX League (Est 1948) D X March 2014 Volume 66 Number 5 LEAGUE LEAGUE

N.Z. RADIO N.Z. RADIO New Zealand DX Times Monthly Journal of the D X New Zealand Radio DX League (est 1948) D X March 2014 Volume 66 Number 5 LEAGUE http://www.radiodx.com LEAGUE Deadline for next issue is Wed 2nd Apr 2014 . P.O Box 178, Mangawhai 0540 Old Radio Hauraki sticker from the CONTENTS FRONT COVER 1980’s. Bryan Clark Bandwatch Under 9 4 X-Band 30 with Ken Baird with Tony King Bandwatch Over 9 9 Branch News 32 with Kelvin Brayshaw with Chief Editor English in Time Order 13 ADCOM News 34 with Yuri Muzyka with Bryan Clark Shortwave Report 15 Ladders 44 with Ian Cattermole by Stuart Forsyth DXissimo 19 John Durham Utilities 21 with Arthur De Maine OTHER TV/FM 24 with Adam Claydon On the Shortwaves 36 Mailbag (On Holiday) by Jerry Berg with Theo Donnelly 14 Foot Fishing Rod Antenna 38 Broadcast News 26 by Philip Garden Including Trail and Mailbag with Bryan Clark NEW ZEALAND RADIO DX LEAGUE (Inc) The New Zealand Radio DX League (Inc) is a non- We are able to accept VISA or Mastercard (only profit organisation founded in 1948 with the main for International members) aim of promoting the hobby of Radio DXing. Contact Treasurer for more details. The NZRDXL is administered from Auckland NZ Radio DX League, P.O. Box 178, Mangawhai Club Magazine 0540, NEW ZEALAND The NZ DX Times. Published monthly. Registered publication. ISSN 0110-3636 Patron Frank Glen [email protected] Printed by ProCopy Ltd, President Bryan Clark Wellington [email protected] http://www.procopy.co.nz/ Vice President David Norrie © All material contained within this magazine is copy- [email protected] right to the New Zealand Radio DX League and may National Treasurer Phil van de Paverd not be used without written permission (which is here- [email protected] by granted to exchange DX magazines).