STATIONS TWENTIETH EDITION Philip Darrington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2002 7:45 PM THURSDAY 8Th August 2002 Greenhills Community House NERG Inc

NERG NEWS Incorporated 1985 in Victoria Reg No A0006776V - http://nerg.asn.au August 2002 7:45 PM THURSDAY 8th August 2002 Greenhills Community House NERG Inc. At the meeting this month: PO Box 270 Greensborough • Annual General Meeting Victoria 3088 • Inside a Panel Antenna What’s on this month? This month there will be loads to see and do. For a starters it’s August so it’s time for the AGM and the election of office bearers! - That should only take up the first few minutes of the meeting so don’t be late or you’ll get elected to something . Get your agenda items and nominations in quickly. • Birthday Celebrations Next a talk by a well-known club member on the inside secrets of a high gain "panel" • Membership fees are due antenna for mobile phone towers. Later the NERG Birthday Party finishes off Membership Fees Due Now International Lighthouse & the night with the traditional Chocolate Cake A quick reminder to all NERG members that st Lightship Weekend and other goodies. 2002 fees are due from the 1 August. Fees This event runs from 10 am (local EST) are $30 single, $40 family, $20 concession, th th Finally, a reminder that memberships fees Saturday 17 to 10 am Monday 19 August, rising much less than inflation! overlapping the Australian RD contest. are due and Marg will happily accept all Send payment to our treasurer (address on contributions to keep the club going another back of NERG NEWS) or drop in to our next NERGs plans will be discussed at the year. -

On Celestial Wings / Edgar D

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Whitcomb. Edgar D. On Celestial Wings / Edgar D. Whitcomb. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. 1. United States. Army Air Forces-History-World War, 1939-1945. 2. Flight navigators- United States-Biography. 3. World War, 1939-1945-Campaigns-Pacific Area. 4. World War, 1939-1945-Personal narratives, American. I. Title. D790.W415 1996 940.54’4973-dc20 95-43048 CIP ISBN 1-58566-003-5 First Printing November 1995 Second Printing June 1998 Third Printing December 1999 Fourth Printing May 2000 Fifth Printing August 2001 Disclaimer This publication was produced in the Department of Defense school environment in the interest of academic freedom and the advancement of national defense-related concepts. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the United States government. This publication has been reviewed by security and policy review authorities and is cleared for public release. Digitize February 2003 from August 2001 Fifth Printing NOTE: Pagination changed. ii This book is dedicated to Charlie Contents Page Disclaimer........................................................................................................................... ii Foreword............................................................................................................................ vi About the author .............................................................................................................. -

Micro-Broadcasting: License-Free Campus Radio in This Issue: • Carey Junior High School ARC • WEFAX Reception on an Ipad • MT Reviews: MFJ Mini-Frequency Counter

www.monitoringtimes.com Scanning - Shortwave - Ham Radio - Equipment Internet Streaming - Computers - Antique Radio ® Volume 30, No. 9 September 2011 U.S. $6.95 Can. $6.95 Printed in the United States A Publication of Grove Enterprises Micro-Broadcasting: License-Free Campus Radio In this issue: • Carey Junior High School ARC • WEFAX Reception on an iPad • MT Reviews: MFJ Mini-Frequency Counter CONTENTS Vol. 30 No. 9 September 2011 CQ DX from KC7OEK .................................................... 12 www.monitoringtimes.com By Nick Casner K7CAS, Cole Smith KF7FXW and Rayann Brown KF7KEZ Scanning - Shortwave - Ham Radio - Equipment Internet Streaming - Computers - Antique Radio Eighteen years ago Paul Crips KI7TS and Bob Mathews K7FDL wrote a grant ® Volume 30, No. 9 September 2011 U.S. $6.95 through the Wyoming Department of Education that resulted in the establishment Can. $6.95 Printed in the United States A Publication of Grove Enterprises of an amateur radio club station at Carey Junior High School in Cheyenne, Wyoming, known on the air as KC7OEK. Since then some 5,000 students have been introduced to amateur radio; nearly 40 students have been licensed, and last year there were 24 students in the club, seven of whom were ready to test for their own amateur radio licenses. In this article, Carey Junior High School students Nick, Cole and Rayann, all three of whom have received their licenses, relate their experiences with amateur radio both on and off the air. While older hams many times their ages are discouraged Micro-Broadcasting: about the direction of the hobby, these students let us all know that the future of License-Free Campus Radio amateur radio is already in good hands. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR13249 Implementation Status & Results Morocco Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Project (P086877) Operation Name: Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Project (P086877) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 16 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 03-Jan-2014 Country: Morocco Approval FY: 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Office National de l'Electricité et de l'Eau Potable (ONEE) Key Dates Board Approval Date 15-Dec-2005 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2012 Planned Mid Term Review Date 30-Sep-2009 Last Archived ISR Date 20-Jun-2013 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 07-Apr-2006 Revised Closing Date 30-Nov-2014 Actual Mid Term Review Date 30-Jun-2010 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The Project development objective is to support the Government program to increase sustainable access to potable water supply in rural areas, while promoting improved wastewater management and hygiene practices. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost WATER PRODUCTION AND CONVEYANCE 51.35 WATER DISTRIBUTION AND WASTEWATER MANAGEMENT 5.35 INSTITUTIONAL STRENGTHENING AND PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION SUPPORT 3.32 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Public Disclosure Authorized Overall Risk Rating Implementation Status Overview The implementation of works under component 1 is progressing well. The number of water standpoints (SPs) constructed has reached 85% of the end-of-project target. -

New Records of the Family Chalcididae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) from Egypt

Zootaxa 4410 (1): 136–146 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4410.1.7 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:6431DC44-3F90-413E-976F-4B00CFA6CD2B New records of the family Chalcididae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) from Egypt MEDHAT I. ABUL-SOOD1 & NEVEEN S. GADALLAH2,3 1Zoology Department, Faculty of Science (Boys), Al-Azhar University, P.O. Box 11884, Nasr City, Cairo, Egypt. E-mail: [email protected] 2Entomology Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In the present study, a checklist of new records of the family Chalcididae of Egypt is presented based on a total of 180 specimens collected from 24 different Egyptian localities between June 2011 and October 2016, mostly by sweeping and Malaise traps. Nineteen species as well as the subfamily Epitraninae and the genera Bucekia Steffan, Epitranus Walker, Proconura Dodd, and Tanycoryphus Cameron, are newly recorded from Egypt. A single species previously placed in the genus Hockeria is transferred to Euchalcis Dufour as E. rufula (Nikol’skaya, 1960) comb. nov. Key words: Parasitic wasps, Chalcidinae, Dirhininae, Epitraninae, Haltichellinae, new records, new combination Introduction The Chalcididae (Hymenoptera: Chalcidoidea) is a medium-sized family represented by more than 1500 described species in 93 genera (Aguiar et al. 2013; Noyes 2017; Abul-Sood et al. 2018). A large number of described species are classified in the genus Brachymeria Westwood (about 21%), followed by Conura Spinola (20.3%) (Noyes 2017). -

Quantitative Analysis and Correction of Temperature Effects On

sustainability Article Quantitative Analysis and Correction of Temperature Effects on Fluorescent Tracer Concentration Measurement Zhihong Zhang 1,2, Heping Zhu 2,* and Huseyin Guler 3 1 College of Agriculture and Food, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming 650500, China; [email protected] 2 USDA-ARS Application Technology Research Unit, Wooster, OH 44691, USA 3 Department of Agricultural Engineering and Technology, Ege University, 35040 Izmir, Turkey; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-330-263-3871 Received: 20 March 2020; Accepted: 27 May 2020; Published: 2 June 2020 Abstract: To ensure an accurate evaluation of pesticide spray application efficiency and pesticide mixture uniformity, reliable and accurate measurements of fluorescence concentrations in spray solutions are critical. The objectives of this research were to examine the effects of solution temperature on measured concentrations of fluorescent tracers as the simulated pesticides and to develop models to correct the deviation of measurements caused by temperature variations. Fluorescent tracers (Brilliant Sulfaflavine (BSF), Eosin, Fluorescein sodium salt) were selected for tests with the solution temperatures ranging from 10.0 ◦C to 45.0 ◦C. The results showed that the measured concentrations of BSF decreased as the solution temperature increased, and the decrement rate was high at the beginning and then slowed down and tended to become constant. In contrast, the concentrations of Eosin decreased slowly at the beginning and then noticeably increased as temperatures increased. On the other hand, the concentrations of Fluorescein sodium salt had little variations with its solution temperature. To ensure the measurement accuracy, correction models were developed using the response surface methodology to numerically correct the measured concentration errors due to variations with the solution temperature. -

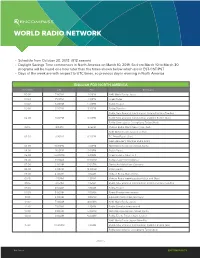

World Radio Network

WORLD RADIO NETWORK • Schedule from October 28, 2018 (B18 season) • Daylight Savings Time commences in North America on March 10, 2019. So from March 10 to March 30 programs will be heard one hour later than the times shown below which are in EST/CST/PST • Days of the week are with respect to UTC times, so previous day in evening in North America ENGLISH FOR NORTH AMERICA UTC/GMT EST PST Programs 00:00 7:00PM 4:00PM NHK World Radio Japan 00:30 7:30PM 4:30PM Israel Radio 01:00 8:00PM 5:00PM Radio Prague 00:30 8:30PM 5:30PM Radio Slovakia Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 02:00 9:00PM 6:00PM Radio New Zealand International: Dateline Pacific (Sun) Radio Guangdong: Guangdong Today (Mon) 02:15 9:15PM 6:15PM Vatican Radio World News (Tue - Sat) NHK World Radio Japan (Tue-Sat) 02:30 9:30PM 6:30PM PCJ Asia Focus (Sun) Glenn Hauser’s World of Radio (Mon) 03:00 10:00PM 7:00PM KBS World Radio from Seoul, Korea 04:00 11:00PM 8:00PM Polish Radio 05:00 12:00AM 9:00PM Israel Radio – News at 8 06:00 1:00AM 10:00PM Radio France International 07:00 2:00AM 11:00PM Deutsche Welle from Germany 08:00 3:00AM 12:00AM Polish Radio 09:00 4:00AM 1:00AM Vatican Radio World News 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Vatican Radio weekly podcast (Sun and Mon) 09:15 4:15AM 1:15AM Radio New Zealand International: Korero Pacifica (Tue-Sat) 09:30 4:30AM 1:30AM Radio Prague 10:00 5:00AM 2:00AM Radio France International 11:00 6:00AM 3:00AM Deutsche Welle from Germany 12:00 7:00AM 4:00AM NHK World Radio Japan 12:30 7:30AM 4:30AM Radio Slovakia International 13:00 -

COMMUNICATION and ADVERTISING This Text Is Prepared for The

DESIGN CHRONOLOGY TURKEY COMMUNICATION AND ADVERTISING This text is prepared for the 3rd Istanbul Design Biennial ARE WE HUMAN? The Design of the Species 2 seconds, 2 days, 2 years, 200 years, 200,000 years by Gökhan Akçura and Pelin Derviş with contributions by Barış Gün and the support of Studio-X Istanbul translated by Liz Erçevik Amado, Selin Irazca Geray and Gülce Maşrabacı editorial support by Ceren Şenel, Erim Şerifoğlu graphic design by Selin Pervan COMMUNICATION AND ADVERTISING 19th CENTURY perfection of the manuscripts they see in Istanbul. Henry Caillol, who grows an interest in and learns about lithography ALAMET-İ FARİKA (TRADEMARK) in France, figures that putting this technique into practice in Let us look at the market places. The manufacturer wants to Istanbul will be a very lucrative business and talks Jacques distinguish his goods; the tradesman wants to distinguish Caillol out of going to Romania. Henry Caillol hires a teacher his shop. His medium is the sign. He wants to give the and begins to learn Turkish. After a while, also relying on the consumer a message. He is trying to call out “Recognize me”. connections they have made, they apply to the Ministry of He is hanging either a model of his product, a duplicate of War and obtain permission to found a lithographic printing the tool he is working with in front of his store, or its sign, house. They place an order for a printing press from France. one that is diferent, interesting. The tailor hangs a pair of This printing house begins to operate in the annex of the scissors and he becomes known as “the one who is good with Ministry of War (the current Istanbul University Rectorate scissors”. -

Some Notes on Diffusion of Qanat

SOME NOTES ON DIFFUSION OF QANAT IWAO KOBORI I. Introductury Remarks The origin and diffusion of Qanat has been among the very important topics to have been studied by scientists, mainly by geographers and historians. The interest which has attracted the study might he due to its very wide distribu- tion all over the world and its close relationship to the arid environment. Al- though several studies on this topic have been published, no definite hypothesis has been widely accepted. From 1956 on, the author has had the same interest as his forerunners but with some difference in viewpoint. His standpoint is, at first, to observe Qanat in situ in their respective areas and synthesize as much as possible. The elabo- rate hypothesis of Qanat origin, i. e. the Achaemenid origin, or the diffusion of Qanat by the hand of Arabs or Spanish Conquistadores is fairly interesting, but is supported by little documentation. For example, the introduction of Qanat into Chinese Turkestam, is still a big theme to be resolved, i, e. when this Chinese Qanat, (kan-erh-ch'ing) was introduced from Persia. In the case of Chinese Turkestan, one document places this introduction in the 18th century, the other in the 2nd century B. C. The other example is a Qanat in South America. It is very easy to say that Qanat was introduced by Spanish Conquistandores from the Iberian Peninsula. However, recent archaeological exacavation may re- verse this hypothesis from the view point of the Pre-Incaic irrigation culture. The technique of Qanat construction is about the same in the different regions. -

AN 307: Altera Design Flow for Xilinx Users Supersedes Information Published in Previous Versions

Altera Design Flow for Xilinx Users June 2005, ver. 5.0 Application Note 307 Introduction Designing for Altera® Programmable Logic Devices (PLDs) is very similar, both in concept and in practice, to designing for Xilinx PLDs. In most cases, you can simply import your register transfer level (RTL) into Altera’s Quartus® II software and begin compiling your design to the target device. This document will demonstrate the similar flows between the Altera Quartus II software and the Xilinx ISE software. For designs, which the designer has included Xilinx CORE generator modules or instantiated primitives, the bulk of this document guides the designer in design conversion considerations. Who Should Read This Document The first and third sections of this application note are designed for engineers who are familiar with the Xilinx ISE software and are using Altera’s Quartus II software. This first section describes the possible design flows available with the Altera Quartus II software and demonstrates how similar they are to the Xilinx ISE flows. The third section shows you how to convert your ISE constraints into Quartus II constraints. f For more information on setting up your design in the Quartus II software, refer to the Altera Quick Start Guide For Quartus II Software. The second section of this application note is designed for engineers whose design code contains Xilinx CORE generator modules or instantiated primitives. The second section provides comprehensive information on how to migrate a design targeted at a Xilinx device to one that is compatible with an Altera device. If your design contains pure behavioral coding, you can skip the second section entirely. -

Egyptian Interest in the Oases in the New Kingdom and a New Stela for Seth from Mut El-Kharab

Egyptian Interest in the Oases in the New Kingdom and a New Stela for Seth from Mut el-Kharab Colin Hope and Olaf Kaper The study of ancient interaction between Egypt and the occupants of regions to the west has focused, quite understandably, upon the major confrontations with the groups now regularly referred to as Liby- ans from the time of Seti I to Ramesses III, and the impact these had upon Egyptian society.1 The situ- ation in the oases of the Western Desert and the role they might have played during these conflicts has not received, until recently, much attention, largely because of the paucity of information either from the Nile Valley or the oases themselves. Yet, given their strategic location, it is not unrealistic to imagine that their control would have been of importance to Egypt both during the confrontations and in the period thereafter. In this short study we present a summary of recently discovered material that contributes sig- nificantly to this question, with a focus upon discoveries made at Mut el-Kharab since excavations com- menced there in 001,3 and a more detailed discussion of one object, a new stela with a hymn dedicated to Seth, which is the earliest attestation of his veneration at the site. We hope that the comments will be of interest to the scholar to whom this volume is dedicated; they are offered with respect, in light of the major contribution he has made to Ramesside studies, and with thanks for his dedication as a teacher and generosity as a colleague. -

Digital Audio Broadcasting : Principles and Applications of Digital Radio

Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Digital Audio Broadcasting Digital Audio Broadcasting Principles and Applications of Digital Radio Second Edition Edited by WOLFGANG HOEG Berlin, Germany and THOMAS LAUTERBACH University of Applied Sciences, Nuernberg, Germany Copyright ß 2003 John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England Telephone (þ44) 1243 779777 Email (for orders and customer service enquiries): [email protected] Visit our Home Page on www.wileyeurope.com or www.wiley.com All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher. Requests to the Publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England, or emailed to [email protected], or faxed to (þ44) 1243 770571. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the Publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.