MACZAC Hotspots 2/10/2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Island of Maui

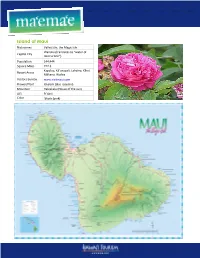

Island of Maui Nicknames Valley Isle; the Magic Isle Wailuku (translates to "water of Capital City destruction") Population 144,444 Square Miles 727.3 Kapalua, Kā‘anapali, Lahaina, Kīhei, Resort Areas Mākena, Wailea Visitors Bureau www.visitmaui.com Flower/Plant lokelani (also roselani) Mountain Haleakalā (House of the sun) Ali'i Pi‘ilani Color ‘ākala (pink) “‘O Maui o nā Hono o Pi‘ilani; Maui nō ka ‘oi” Maui of the Hono bays of Chief Pi‘ilani, Maui is the best MAUI Maui is an island rich with culture and history. The seaport town of Lahaina served as the capital and center of government for the Hawaiian Kingdom from 1820 until 1845. Maui was also an international whaling center in the 19th century where, at one point, 400 whaling ships visited the island during a single season. On November 26, 1778, explorer Captain James Cook became the first European to see Maui. Cook never set foot on the island, however, because he was unable to find a suitable landing. Kamehameha I invaded Maui in 1790 and fought the Battle of Kepaniwai. It wasn’t until a few years later that he finally subdued Maui. Hāna Ranch, Maui Sites of Interest Kā‘anapali Beach The Kā‘anapali area was once a retreat for the high chiefs of Maui. Along this coast is a cliff called Keka‘a, also known as Black Rock. This sacred site is believed to be a place where souls jump off into the spirit world. ‘Īao Valley State Park The Battle of Kepaniwai was a significant battle in Kamehameha’s unification efforts, upon which his forces defeated Maui’s army, led by the Chief Kahekili. -

Spr in G 20 19

SPRING 2019 SPRING JOURNAL OF ACADEMIC RESEARCH & WRITING | Kapi‘olani Community College Board of Student Publications Kapi‘olani Community College 4303 Diamond Head Road Honolulu, HI 96816 1| Ka Hue Anahā Journal of Academic Research & Writing | 2 SPRING 2019 SPRING JOURNAL OF ACADEMIC RESEARCH & WRITING Board of Student Publications | Kapi‘olani Community College 4303 DIAMOND HEAD ROAD HONOLULU, HI 96816 Acknowledgments Works selected for publication were chosen TO FUTURE AUTHORS to reflect the ideas and quality of writing The KCC Board of Student Publications looks across a wide range of courses here at the forward to reading your work in subsequent College. The Faculty Writing Coordinator editions of Ka Hue Anahā Journal of Academic and the Review and Editing Staff would & Research Writing. It is your efforts that keep like to congratulate the authors whose this publication going, and your support and papers were selected for the Spring enthusiasm are sincerely appreciated. 2018 edition of Ka Hue Anahā Journal of Academic & Research Writing, and to Remember to follow the College’s News and acknowledge and encourage all students Events (https://news.kapiolani.hawaii.edu/) who submitted papers. We regret not for information and calls for submissions. being able to publish all of the fine work You can also submit work anytime online submitted this semester. We hope that (http://go.hawaii.edu/ehj) or by contacting you will continue to write, and to engage the Board of Student Publications with the Board of Student Publications by at [email protected]. submitting more work in the future. Furthermore, and with much appreciation, TO FACULTY we would like to extend a sincere thank Please encourage your students to read and you to the faculty, staff and administrators, critically analyse works published in Ka Hue without whose support these student voices Anahā, and to submit their own work for would not be heard. -

Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons All Theses & Dissertations Student Scholarship 2014 Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840 Anatole Brown MA University of Southern Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd Part of the Other American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Anatole MA, "Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England's Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778-1840" (2014). All Theses & Dissertations. 62. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/etd/62 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIMINAL ENCOUNTERS AND THE MISSIONARY POSITION: NEW ENGLAND’S SEXUAL COLONIZATION OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS, 1778–1840 ________________________ A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF THE ARTS THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE AMERICAN AND NEW ENGLAND STUDIES BY ANATOLE BROWN _____________ 2014 FINAL APPROVAL FORM THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE AMERICAN AND NEW ENGLAND STUDIES June 20, 2014 We hereby recommend the thesis of Anatole Brown entitled “Liminal Encounters and the Missionary Position: New England’s Sexual Colonization of the Hawaiian Islands, 1778 – 1840” Be accepted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Professor Ardis Cameron (Advisor) Professor Kent Ryden (Reader) Accepted Dean, College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis has been churning in my head in various forms since I started the American and New England Studies Masters program at The University of Southern Maine. -

American Imperialism and the Annexation of Hawaii

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1933 American imperialism and the annexation of Hawaii Ruth Hazlitt The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Hazlitt, Ruth, "American imperialism and the annexation of Hawaii" (1933). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1513. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1513 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN IMPERIALISM AND THE ANNEXATION OF liAWAII by Ruth I. Hazlitt Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. State University of Montana 1933 Approved Chairman of Examining Committee Chairman of Graduate Committee UMI Number: EP34611 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI EP34611 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest' ProQuest LLC. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 Cover Art from Einaudi Center Events and the Fall 2016 Student Photo Competition (From Top Left, Photo Credit in Parenthesis)

MARIO EINAUDI Center for International Studies ANNUAL REPORT 2016-2017 Cover Art from Einaudi Center events and the Fall 2016 student photo competition (from top left, photo credit in parenthesis): Conference on sustainability in Asia (by Tommy Tan, Hong Kong); Cornell International Fair (by Gail Fletcher); Bartels Lecture by Svetlana Alexievich (by University Photography); Distinguished Speaker Naoto Kan (by Gail Fletcher); "Kenyan Hospitality", Kenya (by Guarav Toor); Distinguished Speaker Mohamed Abdel-Kader (by Gail Fletcher); Annual Reception (by Shai Eynav); Symposium in Zambia on African income inequality (by IAD); "Fishermen", Lebanon (by Zeynep Goksel); Palonegro performance (by LASP); Nepal and Himalayan Studies conference (by SAP); CCCI & CICER student symposium (by EAP); Cornell in Cambodia (by SEAP); "Tortillas de Maiz", Mexico (by Nathan Kalb) 1. Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies.......................................................1 2. International Relations Minor...................................................................................24 3. Comparative Muslim Societies Program..................................................................27 4. Cornell Institute for European Studies.................................................................... 35 5. East Asia Program...................................................................................................... 42 6. Institute for African Development............................................................................ 58 7. Judith -

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print. -

A Portrait of EMMA KAʻILIKAPUOLONO METCALF

HĀNAU MA KA LOLO, FOR THE BENEFIT OF HER RACE: a portrait of EMMA KAʻILIKAPUOLONO METCALF BECKLEY NAKUINA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HAWAIIAN STUDIES AUGUST 2012 By Jaime Uluwehi Hopkins Thesis Committee: Jonathan Kamakawiwoʻole Osorio, Chairperson Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa Wendell Kekailoa Perry DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Kanalu Young. When I was looking into getting a graduate degree, Kanalu was the graduate student advisor. He remembered me from my undergrad years, which at that point had been nine years earlier. He was open, inviting, and supportive of any idea I tossed at him. We had several more conversations after I joined the program, and every single one left me dizzy. I felt like I had just raced through two dozen different ideas streams in the span of ten minutes, and hoped that at some point I would recognize how many things I had just learned. I told him my thesis idea, and he went above and beyond to help. He also agreed to chair my committee. I was orignally going to write about Pana Oʻahu, the stories behind places on Oʻahu. Kanalu got the Pana Oʻahu (HWST 362) class put back on the schedule for the first time in a few years, and agreed to teach it with me as his assistant. The next summer, we started mapping out a whole new course stream of classes focusing on Pana Oʻahu. But that was his last summer. -

Cultural Impact Assessment

Cultural Impact Assessment for the Honouliuli/Waipahu/Pearl City Wastewater Facilities, Honouliuli, Hō‘ae‘ae, Waikele, Waipi‘o, Waiawa, and Mānana, and Hālawa Ahupua‘a, ‘Ewa District, O‘ahu Island TMK: [1] 9-1, 9-2, 9-4, 9-5, 9-6, 9-7, 9-8, 9-9 (Various Plats and Parcels) Prepared for AECOM Pacific, Inc. Prepared by Brian Kawika Cruz, B.A., Constance R. O’Hare, B.A., David W. Shideler, M.A., and Hallett H. Hammatt, Ph.D. Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i, Inc Kailua, Hawai‘i (Job Code: HONOULIULI 35) April 2011 O‘ahu Office Maui Office P.O. Box 1114 16 S. Market Street, Suite 2N Kailua, Hawai‘i 96734 Wailuku, Hawai‘i 96793 www.culturalsurveys.com Ph.: (808) 262-9972 Ph: (808) 242-9882 Fax: (808) 262-4950 Fax: (808) 244-1994 Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i Job Code: HONOULIULI 35 Prefatory Remarks on Language and Style Prefatory Remarks on Language and Style A Note about Hawaiian and other non-English Words: Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i (CSH) recognizes that the Hawaiian language is an official language of the State of Hawai‘i, it is important to daily life, and using it is essential to conveying a sense of place and identity. In consideration of a broad range of readers, CSH follows the conventional use of italics to identify and highlight all non-English (i.e., Hawaiian and foreign language) words in this report unless citing from a previous document that does not italicize them. CSH parenthetically translates or defines in the text the non-English words at first mention, and the commonly-used non-English words and their translations are also listed in the Glossary of Hawaiian Words (Appendix A) for reference. -

MAUI: the MAGIC ISLE Stand Above a Sea of Clouds High Atop Haleakala

MAUI: THE MAGIC ISLE Stand above a sea of clouds high atop Haleakala. Watch a 45- foot whale breach off the coast of Lahaina. Lose count of the waterfalls along the road as you maneuver the hairpin turns of the Hana highway. One visit and it’s easy to see why Maui is called “The Magic Isle.” The second largest Hawaiian island has a smaller population than you’d expect, making Maui popular with visitors who are looking for sophisticated diversions and amenities in the small towns and airy resorts spread throughout the island. From the scenic slopes of fertile Upcountry Maui to beaches that have repeatedly been voted among the best in the world, a visit to the Magic Isle recharges the senses. But like every good magic trick, you’ll have to see it for yourself to believe it. YOUR FIRST TRIP TO MAUI The thought of lying on sun soaked beaches regularly named “the best” by travel magazines is enough to make any of your friends jealous. But once you arrive on Maui, you’ll see there’s so much more for them to envy. Most flights arrive at Maui’s main airport, Kahului Airport (OGG). Many airlines fly direct to Maui while others include Maui as a stopover. You’ll find resorts and hotels of every size and budget in Kapalua, Kaanapali, Lahaina, Kihei, Makena and Wailea on the sunny western coast as well as one resort in Hana in East Maui. It’s about a 45-minute drive from Kahului Airport to Lahaina. Once you’ve settled in you’ll want to explore Maui’s sweeping canvas of attractions. -

Table 4. Hawaiian Newspaper Sources

OCS Study BOEM 2017-022 A ‘Ikena I Kai (Seaward Viewsheds): Inventory of Terrestrial Properties for Assessment of Marine Viewsheds on the Main Eight Hawaiian Islands U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region August 18, 2017 Cover image: Viewshed among the Hawaiian Islands. (Trisha Kehaulani Watson © 2014 All rights reserved) OCS Study BOEM 2017-022 Nā ‘Ikena I Kai (Seaward Viewsheds): Inventory of Terrestrial Properties for Assessment of Marine Viewsheds on the Eight Main Hawaiian Islands Authors T. Watson K. Ho‘omanawanui R. Thurman B. Thao K. Boyne Prepared under BOEM Interagency Agreement M13PG00018 By Honua Consulting 4348 Wai‘alae Avenue #254 Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96816 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region August 18, 2016 DISCLAIMER This study was funded, in part, by the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Environmental Studies Program, Washington, DC, through Interagency Agreement Number M13PG00018 with the US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. This report has been technically reviewed by the ONMS and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and has been approved for publication. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. REPORT AVAILABILITY To download a PDF file of this report, go to the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Environmental Studies Program Information System website and search on OCS Study BOEM 2017-022. -

Download the Conference Brochure

UH Master Gardener 2014 Statewide Conference October 24-26, 2014 REGISTRATION PACKAGE Aloha Master Gardeners, Family, & Friends, Welcome to the 2014 Master Gardener Conference: “Celebrating 100 Years of Extending Knowledge and Changing Lives.” This year we are gathering on Maui. The conference runs Friday, October 24th to Sunday, October 26th. Come to Maui and see why it is “N¯o Ka ‘Oi.” Friday night is Upcountry in Pukalani. Come and enjoy food and drinks, static displays, and maybe even some fun and games with us while we watch the sunset from the slopes of Haleakal¯a. If you will need a ride up, check the transportation box and we’ll arrange one for you. The welcome and registration event will run from 5PM to 8PM and is free to everyone. Saturday, take a tour and visit a side of Maui you may not have seen before. Check out the websites of the destinations for more information. After the tour, the banquet will be held right on the beach at the restaurant Cary & Eddie’s Hideaway. The banquet features a buffet, goodie bags, a silent auction, and an awards ceremony. An emcee will round out the evening. Sunday is an advanced education day with many great choices. Both Saturday and Sunday, we will have a continental breakfast at the college. For accommodations, we have set up a block of rooms at the beachfront Maui Seaside (877-3311). Mention “UH Master Gardener” when you make your reservations for the Kama‘¯aina rate of $99. The hotel is a short 10-minute walk from the college, where everything is beginning, and the banquet is located across the parking lot. -

Ka'iana, the Once Famous "Prince of Kaua'i3

DAVID G. MILLER Ka'iana, the Once Famous "Prince of Kaua'i3 KA'IANA WAS SURELY the most famous Hawaiian in the world when he was killed in the battle of Nu'uanu in 1795, at the age of 40. He was the first Hawaiian chief who had traveled abroad, having in 1787-1788 visited China, the Philippines, and the Northwest Coast of America. In China, according to Captain Nathaniel Portlock, "his very name [was] revered by all ranks and conditions of the people of Canton."1 Books published in London in 1789 and 1790 by Portlock and Captain John Meares about their voyages in the Pacific told of Ka'iana's travels, and both included full-page engravings of the handsome, muscular, six-foot-two chief arrayed in his feathered cloak and helmet, stalwartly gripping a spear (figs. 1 and 2). Meares, on whose ships Ka'iana had sailed, captioned the portrait as "Tianna, a Prince of Atooi" (Kaua'i) and made Ka'iana "brother to the sovereign" of Kaua'i, a central character in his narrative.2 In the early 1790s, it was Ka'iana whom many foreign voyagers had heard of and sought out when visiting the Hawaiian Islands. Islanders from Kaua'i to Hawai'i knew Ka'iana personally as a warrior chief who had resided and fought on the major islands and who shifted his allegiance repeatedly among the ruling chiefs of his time. Today, when Ka'iana is remembered at all, he is likely to be David G. Miller, a Honolulu resident, has been researching biographical information on Hawaiian chiefs and chief esses, particularly lesser-known ones.