November 11, 2020 Dr. Alan Downer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Million Pounds of Sandalwood: the History of Cleopatra's Barge in Hawaii

A Million Pounds Of Sandalwood The History of CLEOPATRA’S BARGE in Hawaii by Paul Forsythe Johnston If you want to know how Religion stands at the in his father’s shipping firm in Salem, shipping out Islands I can tell you—All sects are tolerated as a captain by the age of twenty. However, he pre- but the King worships the Barge. ferred shore duty and gradually took over the con- struction, fitting out and maintenance of his fam- Charles B. Bullard to Bryant & Sturgis, ily’s considerable fleet of merchant ships, carefully 1 November expanded from successful privateering during the Re volution and subsequent international trade un- uilt at Salem, Massachusetts, in by Re t i re der the new American flag. In his leisure time, B Becket for George Crowninshield Jr., the her- George drove his custom yellow horse-drawn car- m a p h rodite brig C l e o p a t ra’s Ba r g e occupies a unique riage around Salem, embarked upon several life- spot in maritime history as America’s first ocean- saving missions at sea (for one of which he won a going yacht. Costing nearly , to build and medal), recovered the bodies of American military fit out, she was so unusual that up to , visitors heroes from the British after a famous naval loss in per day visited the vessel even before she was com- the War of , dressed in flashy clothing of his pleted.1 Her owner was no less a spectacle. own design, and generally behaved in a fashion Even to the Crowninshields, re n o w n e d quite at odds with his diminutive stature and port l y throughout the region for going their own way, proportions. -

Pastoral Letter ‘Aukake 2016 August 2016

GLAD TIDINGS Nu ‘Oli Pastoral Letter ‘Aukake 2016 August 2016 Nu ‘Oli / Glad Tidings Kahu Dennis v m WAIOLA CHURCH Members and Friends of Waiola UCC: Aloha Mai; Aloha Aku (United Church of Christ) Congregations, like most other organizations and families, do best when communication is prompt, accurate, focused, and useful. Transparency is crucial 535 Wainee Street to trust within the church, and regular communication is crucial to the endeavor. Lahaina, HI 96761 So it is that we have begun a monthly printed newsletter. Phone/ Fax: 808.661.4349 Facebook and the Waiola web page are of similar importance. It is my goal to see [email protected] that each is both current and inviting. In my experience, seekers find information these days by a group’s “web presence.” The website offers useful historical and logistical information; Facebook provides a day-to-day perspective, as we can post Interim Minister: the Stillspeaking Devotional and up-to-the-minute reminders for interested Kahu Dennis Alger persons. Through these forms of communication, as well as through Sunday reflections, you are able to get an idea about me and what I am up to in our sojourn together. Lay Minister: As a reminder, the kuleana of an interim minister is to build relationships (trust), Kahu Anela Rosa ask a lot of questions (learn from you), offer encouragement (speak and act on your truth), assist in clarifying complicated matters (find a particular tree in the forest), provide feedback (challenge and console), point to your desired future Moderator: (through Profile development and search for your next kahu), and keep a sense of Grale Lorenzo-Chong humor. -

(Letters from California, the Foreign Land) Kānaka Hawai'i Agency A

He Mau Palapala Mai Kalipōnia Mai, Ka ʻĀina Malihini (Letters from California, the Foreign Land) Kānaka Hawai’i Agency and Identity in the Eastern Pacific (1820-1900) By April L. Farnham A thesis submitted to Sonoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Committee Members: Dr. Michelle Jolly, Chair Dr. Margaret Purser Dr. Robert Chase Date: December 13, 2019 i Copyright 2019 By April L. Farnham ii Authorization for Reproduction of Master’s Thesis Permission to reproduce this thesis in its entirety must be obtained from me. Date: December 13, 2019 April L. Farnham Signature iii He Mau Palapala Mai Kalipōnia Mai, Ka ʻĀina Malihini (Letters from California, the Foreign Land) Kānaka Hawai’i Agency and Identity in the Eastern Pacific (1820-1900) Thesis by April L. Farnham ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to explore the ways in which working-class Kānaka Hawai’i (Hawaiian) immigrants in the nineteenth century repurposed and repackaged precontact Hawai’i strategies of accommodation and resistance in their migration towards North America and particularly within California. The arrival of European naturalists, American missionaries, and foreign merchants in the Hawaiian Islands is frequently attributed for triggering this diaspora. However, little has been written about why Hawaiian immigrants themselves chose to migrate eastward across the Pacific or their reasons for permanent settlement in California. Like the ali’i on the Islands, Hawaiian commoners in the diaspora exercised agency in their accommodation and resistance to Pacific imperialism and colonialism as well. Blending labor history, religious history, and anthropology, this thesis adopts an interdisciplinary and ethnohistorical approach that utilizes Hawaiian-language newspapers, American missionary letters, and oral histories from California’s indigenous peoples. -

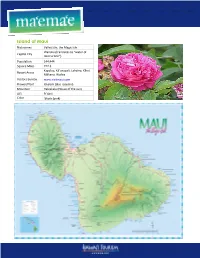

Island of Maui

Island of Maui Nicknames Valley Isle; the Magic Isle Wailuku (translates to "water of Capital City destruction") Population 144,444 Square Miles 727.3 Kapalua, Kā‘anapali, Lahaina, Kīhei, Resort Areas Mākena, Wailea Visitors Bureau www.visitmaui.com Flower/Plant lokelani (also roselani) Mountain Haleakalā (House of the sun) Ali'i Pi‘ilani Color ‘ākala (pink) “‘O Maui o nā Hono o Pi‘ilani; Maui nō ka ‘oi” Maui of the Hono bays of Chief Pi‘ilani, Maui is the best MAUI Maui is an island rich with culture and history. The seaport town of Lahaina served as the capital and center of government for the Hawaiian Kingdom from 1820 until 1845. Maui was also an international whaling center in the 19th century where, at one point, 400 whaling ships visited the island during a single season. On November 26, 1778, explorer Captain James Cook became the first European to see Maui. Cook never set foot on the island, however, because he was unable to find a suitable landing. Kamehameha I invaded Maui in 1790 and fought the Battle of Kepaniwai. It wasn’t until a few years later that he finally subdued Maui. Hāna Ranch, Maui Sites of Interest Kā‘anapali Beach The Kā‘anapali area was once a retreat for the high chiefs of Maui. Along this coast is a cliff called Keka‘a, also known as Black Rock. This sacred site is believed to be a place where souls jump off into the spirit world. ‘Īao Valley State Park The Battle of Kepaniwai was a significant battle in Kamehameha’s unification efforts, upon which his forces defeated Maui’s army, led by the Chief Kahekili. -

Spr in G 20 19

SPRING 2019 SPRING JOURNAL OF ACADEMIC RESEARCH & WRITING | Kapi‘olani Community College Board of Student Publications Kapi‘olani Community College 4303 Diamond Head Road Honolulu, HI 96816 1| Ka Hue Anahā Journal of Academic Research & Writing | 2 SPRING 2019 SPRING JOURNAL OF ACADEMIC RESEARCH & WRITING Board of Student Publications | Kapi‘olani Community College 4303 DIAMOND HEAD ROAD HONOLULU, HI 96816 Acknowledgments Works selected for publication were chosen TO FUTURE AUTHORS to reflect the ideas and quality of writing The KCC Board of Student Publications looks across a wide range of courses here at the forward to reading your work in subsequent College. The Faculty Writing Coordinator editions of Ka Hue Anahā Journal of Academic and the Review and Editing Staff would & Research Writing. It is your efforts that keep like to congratulate the authors whose this publication going, and your support and papers were selected for the Spring enthusiasm are sincerely appreciated. 2018 edition of Ka Hue Anahā Journal of Academic & Research Writing, and to Remember to follow the College’s News and acknowledge and encourage all students Events (https://news.kapiolani.hawaii.edu/) who submitted papers. We regret not for information and calls for submissions. being able to publish all of the fine work You can also submit work anytime online submitted this semester. We hope that (http://go.hawaii.edu/ehj) or by contacting you will continue to write, and to engage the Board of Student Publications with the Board of Student Publications by at [email protected]. submitting more work in the future. Furthermore, and with much appreciation, TO FACULTY we would like to extend a sincere thank Please encourage your students to read and you to the faculty, staff and administrators, critically analyse works published in Ka Hue without whose support these student voices Anahā, and to submit their own work for would not be heard. -

Honolulu Advertiser & Star-Bulletin Obituaries January 1

Honolulu Advertiser & Star-Bulletin Obituaries January 1 - December 31, 2004 K ANNIE "TAXI ANNIE" AKI KA, 78, of Kailua, Hawai'i, died Aug. 12, 2004. Born in Honaunau, Hawai'i. A professional lei maker, lei wholesaler, and professional hula dancer; member of 'Ahahui Ka'ahumanu O Kona (Ka'ahumanu Society, Kona); owner of Triple K Taxi Service; longtime Jack's Tours and Taxi Service employee; owner of a bicycle rental business, and Kona Inn Hotel bartender. Survived by sons, Joseph Sr., Harry and Jonathan; daughters, Annie Leong and Lorraine Wahinekapu; 13 grandchildren; 17 great-grandchildren; brothers, Archie, Ernest and Walter Aki; sisters, Lillian Hose, Dolly Salas and Elizabeth Aki. Visitation 8:30 to 10 a.m. Saturday at Lanakila Church, Kainaliu, Hawai'i; memorial service 10 a.m.; burial of urn to follow in church cemetery. No flowers; monetary donations accepted. Casual attire. Arrangements by Dodo Mortuary, Kona, Hawai'i. [Adv Aug 24, 2004] MYRTLE KAPEAOKAMOKU KAAA, 75, of Hilo, Hawai'i, died April 18, 2004. Born in Kapapala, Ka'u, Hawai'i. A homemaker. Survived by husband, William Jr.; sons, Kyle and Kelsey; daughter, Kawehi Walters and Kimelia Ishibashi; sister, Iris Boshard; 15 grandchildren; five great- grandchildren. Visitation 10 a.m. to noon Saturday at Haili Congregational Church; service noon; burial to follow at Hawai'i Veterans Cemetery No. 2. Aloha attire. Arrangements by Dodo Mortuary, Hilo. [Adv 27/04/2004] WILLIAM KELEKINO "JUNIOR" KAAE, 72, of Kane'ohe, died Jan. 17, 2004. Born in Honolulu. Spats nightclub employee; and a Waikiki beachboy. Survived by wife, Georgette; daughters, Danell Soares-Haae, Teresa Marshall and Kuulei; sons, Leonard, Dudley, Joe and Everett; brothers, George, Naleo and Leonard Kaae, and Nick and Sherman Tenn; sisters, Rose Gelter, Ethel Hanley and Wanda Naweli; 18 grandchildren; three great-grandchildren. -

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print. -

MAUI: the MAGIC ISLE Stand Above a Sea of Clouds High Atop Haleakala

MAUI: THE MAGIC ISLE Stand above a sea of clouds high atop Haleakala. Watch a 45- foot whale breach off the coast of Lahaina. Lose count of the waterfalls along the road as you maneuver the hairpin turns of the Hana highway. One visit and it’s easy to see why Maui is called “The Magic Isle.” The second largest Hawaiian island has a smaller population than you’d expect, making Maui popular with visitors who are looking for sophisticated diversions and amenities in the small towns and airy resorts spread throughout the island. From the scenic slopes of fertile Upcountry Maui to beaches that have repeatedly been voted among the best in the world, a visit to the Magic Isle recharges the senses. But like every good magic trick, you’ll have to see it for yourself to believe it. YOUR FIRST TRIP TO MAUI The thought of lying on sun soaked beaches regularly named “the best” by travel magazines is enough to make any of your friends jealous. But once you arrive on Maui, you’ll see there’s so much more for them to envy. Most flights arrive at Maui’s main airport, Kahului Airport (OGG). Many airlines fly direct to Maui while others include Maui as a stopover. You’ll find resorts and hotels of every size and budget in Kapalua, Kaanapali, Lahaina, Kihei, Makena and Wailea on the sunny western coast as well as one resort in Hana in East Maui. It’s about a 45-minute drive from Kahului Airport to Lahaina. Once you’ve settled in you’ll want to explore Maui’s sweeping canvas of attractions. -

2008 Annual Building Permits Detail

COUNTY OF MAUI DEVELOPMENT SERVICES ADMINISTRATION BUILDING PERMITS ISSUED 250 SOUTH HIGH STREET Run Date 1/6/10 WAILUKU, HI 96793 Page 1 of 155 (808) 270-7250 FAX (808) 270-7972 January 01, 2008 to December 31, 2008 Project Name/ Property Owner Description/ Location # Units Valuation Builder 101 SINGLE FAMILY, DETACHED 535 $152,951,147.00 1 B-20080001 MONIZ, HAROLD AND AUDREY 1ST FARM DWELLING/GARAGE (1000SF) 1.00 $127,320.00 B FLORO DELLA 1/2/2008 SHAMMAH LTD PART(B) 600 LUAHOANA PL WAILUKU TMK 3-3-017:044 2,426 sf 2 B-20080006 WARFEL, ROLAND MAIN DWELLING / GARAGE 1.00 $250,000.00 B JOHN L. MAXFIELD 1/3/2008 WARFEL,ROLAND HANS 36 NAMAUU PL KIHEI TMK 3-9-022:007 2,408 sf 3 B-20080009 VIDINHAR, STANLEY MAIN DWELLING/GARAGE/COVERED LANAI 1.00 $242,520.00 B RKC CONSTRUCTION 1/3/2008 VIDINHAR, STANLEY 48 KOANI LOOP WAILUKU TMK 3-5-032:010 3,221 sf 4 B-20080012 KAOPUIKI, GAY 1ST FARM DWELLING (<1000SF) 1.00 $83,000.00 X7 OWNER BUILDER 1/3/2008 KAOPUIKI, GAY 3184 MAUNALOA HWY HOOLEHUA TMK 5-2-004:096 sf 5 B-20080014 MOORE, WILLIAM B MAIN DWELLING 1.00 $200,000.00 X7 OWNER BUILDER 1/3/2008 MOORE,WILLIAM BAXTER 288 KAIWI ST KAUNAKAKAI TMK 5-3-008:077 3,000 sf 6 B-20080015 MIDDLETON, EULIE 2ND FARM DWL/COV LANAI/CARPORT 1.00 $114,680.00 X7 OWNER BUILDER 1/3/2008 MIDDLETON,EULIE L 955 KAUHIKOA RD HAIKU TMK 2-7-008:004 1,586 sf 7 B-20080016 KAMALAII ALAYNA PHASE 2 LOT 28 - DWELLING/GARAGE 1.00 $189,070.00 B BETSILL BROTHERS 1/4/2008 WAIPUILANI ASSOCIATES,LLC KIHEI TMK 3-9-059:003 2,733 sf CONSTRUCTION 8 B-20080017 KAMALII ALAYNA PH2 - LOT 30 MODEL -

Kekuaokalani: an Historical Fiction Exploration of the Hawaiian Iconoclasm

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Undergraduate Honors Theses 2018-12-07 Kekuaokalani: An Historical Fiction Exploration of the Hawaiian Iconoclasm Alex Oldroyd Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Oldroyd, Alex, "Kekuaokalani: An Historical Fiction Exploration of the Hawaiian Iconoclasm" (2018). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 54. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht/54 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Honors Thesis KEKUAOKALANI: AN HISTORAL FICTION EXPLORATION OF THE HAWAIIAN ICONOCLASM by Alexander Keone Kapuni Oldroyd Submitted to Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of graduation requirements for University Honors English Department Brigham Young University December 2018 Advisor: John Bennion, Honors Coordinator: John Talbot ABSTRACT KEKUAOKALANI: AN HISTORAL FICTION EXPLORATION OF THE HAWAIIAN ICONOCLASM Alexander K. K. Oldroyd English Department Bachelor of Arts This thesis offers an exploration of the Hawaiian Iconoclasm of 1819 through the lens of an historical fiction novella. The thesis consists of two parts: a critical introduction outlining the theoretical background and writing process and the novella itself. 1819 was a year of incredible change on Hawaiian Islands. Kamehameha, the Great Uniter and first monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, had recently died, thousands of the indigenous population were dying, and foreign powers were arriving with increasing frequency, bringing with them change that could not be undone. -

Download the Conference Brochure

UH Master Gardener 2014 Statewide Conference October 24-26, 2014 REGISTRATION PACKAGE Aloha Master Gardeners, Family, & Friends, Welcome to the 2014 Master Gardener Conference: “Celebrating 100 Years of Extending Knowledge and Changing Lives.” This year we are gathering on Maui. The conference runs Friday, October 24th to Sunday, October 26th. Come to Maui and see why it is “N¯o Ka ‘Oi.” Friday night is Upcountry in Pukalani. Come and enjoy food and drinks, static displays, and maybe even some fun and games with us while we watch the sunset from the slopes of Haleakal¯a. If you will need a ride up, check the transportation box and we’ll arrange one for you. The welcome and registration event will run from 5PM to 8PM and is free to everyone. Saturday, take a tour and visit a side of Maui you may not have seen before. Check out the websites of the destinations for more information. After the tour, the banquet will be held right on the beach at the restaurant Cary & Eddie’s Hideaway. The banquet features a buffet, goodie bags, a silent auction, and an awards ceremony. An emcee will round out the evening. Sunday is an advanced education day with many great choices. Both Saturday and Sunday, we will have a continental breakfast at the college. For accommodations, we have set up a block of rooms at the beachfront Maui Seaside (877-3311). Mention “UH Master Gardener” when you make your reservations for the Kama‘¯aina rate of $99. The hotel is a short 10-minute walk from the college, where everything is beginning, and the banquet is located across the parking lot. -

BABIN, FRANCES SHERRILL, 85, of Kailua, Died May 29, 2010. Born in Memphis, Tenn

BABIN, FRANCES SHERRILL, 85, of Kailua, died May 29, 2010. Born in Memphis, Tenn. Homemaker and librarian. Survived by son, Mark; daughter, Sherry Babin Nolte; grandchildren, Miles Nolte, Sarah Bauer, Jon and Michel. Service 5 p.m. Wednesday at St. Christopher's Church, Kailua. In lieu of flowers, donations to Family Promise of Hawaii. Arrangements by Ultimate Cremation Services of Hawaii. [Honolulu Advertiser 3 June 2010] Babin, Frances Sherrill, May 29, 2010 Frances Sherrill Babin, 85, of Kailua, a homemaker and librarian, died in Kailua. She was born in Memphis, Tenn. She is survived by son Mark, daughter Sherry B. Nolte and four grandchildren. Services: 5 p.m. Wednesday at St. Christopher's Church, Kailua. No flowers. Donations suggested to Family Promise of Hawaii. [Honolulu Star Bulletin 4 June 2010] Baclig, Buena Sabangan, June 12, 2010 Buena Sabangan Baclig, 95, of Kapolei died in Atwater, Calif. She was born in Cabugao, Ilocos Sur, Philippines. She is survived by son Epifanio; daughter Venancia Asuncion; brothers Jose and Eugene Sabangan; sister Maria Sabangan; three grandchildren; and six great-grandchildren. Services: 6:15 p.m. Tuesday at Mililani Mortuary-Waipio, makai chapel. Call after 5:30 p.m. Mass: 11 a.m. Wednesday at Our Lady of Good Council Catholic Church, 1525 Waimano Home Road, Pearl City. Call after 10:30 a.m. Burial: 1 p.m. at Valley of the Temples. [Honolulu Advertiser 27 June 2010] BADOYEN, ERIC "SAM" G., 55, of Honolulu, died May 16, 2010. Born in Lahaina, Maui. Former automobile salesman and Borthwick Mortuary employee. Survived by, Eric "Kekoa," Christopher "Baba," Shawn "Kamana" and Kyle; daughter, BrittanyLeigh "Kai"; former wife, Charlotte "Pikake" Thomas-Badoyen; 10 grandchildren; three great-grandchildren; brothers, James, Felipe, Gerald, Andrew, Wallace, John and Dexter; sister, Marlena Robinson.