Why Genetic Arguments for Acheulean Handaxes Are More Like Singing the Blues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Human Evolutionary Calendar - Evolution in a Year)I------1 January • December F------{( March ) ( June September

The Human Evolutionary Calendar - Evolution in a Year)I---------1 January • December f-------{( March ) ( June September SahelanthropusTchadensi Australopithecus sediba Homo rh odes iensis Ardipithecus ramidus 7,000,000 - 6,000,000 yrs. 2,000,000 - , ,750,000 yrs. 300,000 -125,000 yrs. 3,200,000 • 4,300,000 yrs. Homo rudolfensis Orrorin tugenensis 1,900,000 - 1.750,000 yrs. Homo pekin ensi s 6, 100,000 - 5,BOO,Oci:l yrs. 700,000 - 500,000 yrs. Australopit ec us anamensis 4,200,00 - 3,900,000 yrs. Ardipithecus kadabba 5,750,000 - 5,200,000 yrs. Ho m o Ergaster 1,900,000 - 1,3,000,000 yrs. Homo heidelberge nsis 700,000 • 200,000 yrs. Australopithecus afarensis Homo erectus 3,900,000 - 2,900,000 yrs. 1,800,000 • 250,000 yrs. Ho mo antecessor Australopithecus africa nus Ho mo habilis 1,000,000 -700,000 yrs. 3,800,000 - 3,000,000 yrs. 2,350,000 - 1,450,000 yrs. Ho m o g eorgicus Kenya nthropus platyo ps 1,800,000- 1.3000,000 yrs. 3,500,000 - 3,200,000 yrs. Ho m o nea nderthalensis 200,000 · 28,000 yrs. Paranthropus bo ise i Paranthropus aethiopicu 2,275,000- 1,250,000 yrs. De nisova ho minins 2,650,000 - 2,300,000 yrs. 200,000 - 30,000 yrs. Paranthropus robustus/crass iden s Australopithecus garhi 1,750,000- 1,200,000 yrs. 2,750,000 - 2.400,000 yrs. Red Deer Cave Peo ple ?- 11,000yrs. Ho mo sa piens sapien s 200~ Ho m o fl o res iensis 100,000 • 13,000 yrs. -

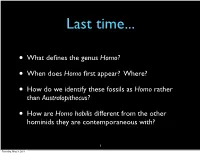

• What Defines the Genus Homo? • When Does Homo First Appear

Last time... • What defines the genus Homo? • When does Homo first appear? Where? • How do we identify these fossils as Homo rather than Australopithecus? • How are Homo habilis different from the other hominids they are contemporaneous with? 1 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 Olduwan tools • What are Olduwan tools? • How are they made? • When are they first found and with which species? 2 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 Adaptive pattern • How does the adaptive pattern of early Homo differ from that of the Australopithecines? • Why was brain size selected for? • What else changes in adaptation when brain size increases? 3 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 H. habilis v. H. erectus • What makes these two species different? • When are they found in time? space? 4 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 Possible Homo species Homo habilis • Sometimes the same • Homo rudolfensis • Homo ergaster Sometimes the same • Homo erectus 5 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 Homo erectus • Who is Homo erectus? • Where is this species found? • In what time frame? • What are its identifying anatomies? 6 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 Homo erectus lifeways • tool technologies that reflect advanced cognitive skills • Dietary shift to a more heavily meat- based diet than its predecessors 7 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 Zhoukoudian 300 kya 8 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 Homo floresiensis 95,000-13,000 9 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 10 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 11 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 Homo antecessor / Homo erectus? Atapuerca Atapuerca 1.2 mya 800,000 12 Tuesday, May 3, 2011 Cranial capacities Cranial Capacity Africa 690-1067 Indonesia 800-1250 China 855-1225 13 Tuesday, -

The Acheulean Handaxe Corbey, Raymond; Collard, Mark; Vaesen, Krist; Jagich, Adam

Tilburg University The Acheulean handaxe Corbey, Raymond; Collard, Mark; Vaesen, Krist; Jagich, Adam Published in: Evolutionary Anthropology DOI: 10.1002/evan.21467 Publication date: 2016 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Corbey, R., Collard, M., Vaesen, K., & Jagich, A. (2016). The Acheulean handaxe: More like a bird’s song than a Beatles’ tune? Evolutionary Anthropology, 25(1), 6-19. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21467 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. sep. 2021 Evolutionary Anthropology 25:6–19 (2016) ARTICLE The Acheulean Handaxe: More Like a Bird’s Song Than a Beatles’ Tune? RAYMOND CORBEY, ADAM JAGICH, KRIST VAESEN, AND MARK COLLARD The goal of this paper is to provoke debate about the nature of an iconic arti- lion square kilometers, multiple eco- fact—the Acheulean handaxe. -

The Origin of Modern Anatomy: by Speciation Or Intraspecific Evolution?

Evolutionary Anthropology 17:22–37 (2008) ARTICLES The Origin of Modern Anatomy: By Speciation or Intraspecific Evolution? GU¨ NTER BRA¨ UER ‘‘Speciation remains the special case, the less frequent and more elusive Over the years, the chronological phenomenon, often arising by default’’ (p 164).1 framework for Africa had to be Over the last thirty years, great progress has been made regarding our under- somewhat revised due to new dating standing of Homo sapiens evolution in Africa and, in particular, the origin of ana- evidence and other discoveries. For tomically modern humans. However, in the mid-1970s, the whole process of example, in 1997, we presented a re- Homo sapiens evolution in Africa was unclear and confusing. At that time it was vised scheme14 in which the time widely assumed that very archaic-looking hominins, also called the ‘‘Rhode- periods of both the early archaic and sioids,’’ which included the specimens from Kabwe (Zambia), Saldanha (South the late archaic groups had to be Africa), and Eyasi (Tanzania), were spread over wide parts of the continent as somewhat extended because of new recently as 30,000 or 40,000 years ago. Yet, at the same time, there were also absolute dates for the Bodo and Flo- indications from the Omo Kibish skeletal remains (Ethiopia) and the Border Cave risbad hominins, among others. The specimens (South Africa) that anatomically modern humans had already been current updated version (Fig. 1) present somewhat earlier than 100,000 years B.P.2,3 Thus, it was puzzling how includes the most recently discovered such early moderns could fit in with the presence of very archaic humans still specimens from Ethiopia as well as existing in Eastern and Southern Africa only 30,000 years ago. -

Reconstructing Human Evolution: Achievements, Challenges, and Opportunities

Reconstructing human evolution: Achievements, challenges, and opportunities Bernard Wood1 George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052 This contribution reviews the evidence that has resolved the can then be used as the equivalent of a null hypothesis when branching structure of the higher primate part of the tree of life considering where to place newly discovered fossil great ape taxa. and the substantial body of fossil evidence for human evolution. It considers some of the problems faced by those who try to interpret The Human Fossil Record. The fossil record of the human clade the taxonomy and systematics of the human fossil record. How do consists of fossil evidence for modern humans plus that of all ex- you to tell an early human taxon from one in a closely related clade? tinct taxa that are hypothesized to be more closely related to How do you determine the number of taxa represented in the modern humans than to any other living taxon. Not so long ago human clade? How can homoplasy be recognized and factored into nearly all researchers were comfortable with according the human attempts to recover phylogeny? clade the status of a family, the Hominidae, with the nonhuman extant great apes (i.e., chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and history | hominin orangutans) placed in a separate family, the Pongidae. But given the abundant evidence for a closer relationship between Pan and his contribution begins by considering two achievements rele- Homo than between Pan and Gorilla (see above), many research- Tvant to reconstructing human evolution: resolving the branch- ers have concluded that the human clade should be distinguished ing structure of the higher primate part of the tree of life and the beneath the level of the family in the Linnaean hierarchy. -

The Internal Cranial Anatomy of the Middle Pleistocene Broken Hill 1 Cranium

The Internal Cranial Anatomy of the Middle Pleistocene Broken Hill 1 Cranium ANTOINE BALZEAU Équipe de Paléontologie Humaine, UMR 7194 du CNRS, Département Homme et Environnement, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, FRANCE; and, Department of African Zoology, Royal Museum for Central Africa, B-3080 Tervuren, BELGIUM; [email protected] LAURA T. BUCK Earth Sciences Department, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD; Division of Biological Anthropology, University of Cambridge, Pembroke Street, Cambridge CB2 3QG; and, Centre for Evolutionary, Social and InterDisciplinary Anthropology, University of Roehampton, Holybourne Avenue, London SW15 4JD, UNITED KINGDOM; [email protected] LOU ALBESSARD Équipe de Paléontologie Humaine, UMR 7194 du CNRS, Département Homme et Environnement, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, FRANCE; [email protected] GAËL BECAM Équipe de Paléontologie Humaine, UMR 7194 du CNRS, Département Homme et Environnement, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, FRANCE; [email protected] DOMINIQUE GRIMAUD-HERVÉ Équipe de Paléontologie Humaine, UMR 7194 du CNRS, Département Homme et Environnement, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, FRANCE; [email protected] TODD C. RAE Centre for Evolutionary, Social and InterDisciplinary Anthropology, University of Roehampton, Holybourne Avenue, London SW15 4JD, UNITED KINGDOM; [email protected] CHRIS B. STRINGER Earth Sciences Department, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UNITED KINGDOM; [email protected] submitted: 20 December 2016; accepted 12 August 2017 ABSTRACT The cranium (Broken Hill 1 or BH1) from the site previously known as Broken Hill, Northern Rhodesia (now Kabwe, Zambia) is one of the best preserved hominin fossils from the mid-Pleistocene. -

Morphometric Analysis of the Herto Cranium (BOU-VP-16/1): Where Does It Fit?

ISSN 2150-3311 JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY ANTHROPOLOGY RESEARCH ARTICLE VOLUME II 2011 ISSUE 1 Morphometric Analysis of the Herto Cranium (BOU-VP-16/1): Where Does It Fit? Kyle D. Lubsen Ph.D. Candidate Department of Anthropology Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois Robert S. Corruccini Ph.D. Department of Anthropology Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois Copyright © Kyle D. Lubsen and Robert S. Corruccini Morphometric Analysis of the Herto Cranium (BOU-VP-16/1): Where Does It Fit? Kyle D. Lubsen Ph.D. Candidate Department of Anthropology Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois Robert S. Corruccini Ph.D. Department of Anthropology Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois ABSTRACT The debate surrounding the initial appearance of anatomically modern Homo sapiens and subsequent evolution into modern Homo sapiens sapiens had centered on two competing hypotheses. The “Multiregional Continuity Model” and the “Out of Africa 2 Model”. Evidence for these models has primarily come from analyses of pertinent fossilized remains and genetic data. White et al. (2003) suggests that their multivariate analyses of one of three fossil crania, from the Herto formation of the Bouri member in the Middle Awash, Ethiopia, places the fossil intermediate between archaic Homo sapiens (i.e., Kabwe) and more modern Homo sapiens (i.e., Qafzeh and Skhul V). This, White et al. (2003) suggests, would be strong evidence for the “Out of Africa 2 Model”, albeit in a somewhat gradualistic sense. The purpose of the study undertaken here is to reanalyze the Herto specimen (i.e. BOU-VP-16-1) using c-score (i.e., shape) principal coordinates and Euclidean distances to determine if the Herto cranium is morphometrically intermediate between archaic Homo sapiens and more modern Homo sapiens sapiens. -

A Rich Locality in South Kensington the Fossil Hominin Collection of The

LJMU Research Online Buck, LT and Stringer, CB A rich locality in South Kensington: the fossil hominin collection of the Natural History Museum, London http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/id/eprint/12692/ Article Citation (please note it is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from this work) Buck, LT and Stringer, CB (2015) A rich locality in South Kensington: the fossil hominin collection of the Natural History Museum, London. Geological Journal, 50 (3). pp. 321-337. ISSN 0072-1050 LJMU has developed LJMU Research Online for users to access the research output of the University more effectively. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LJMU Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of the record. Please see the repository URL above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information please contact [email protected] http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/ A rich locality in South Kensington: the fossil hominin collection of the Natural History Museum, London. Buck, L. T.1,2,* and Stringer, C. B.1 1Human Origins Research Group, Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD. -

The Origin of Neandertals

The origin of Neandertals J. J. Hublin1 Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, 04103 Leipzig, Germany Edited by Richard G. Klein, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, and approved August 6, 2009 (received for review April 14, 2009) Western Eurasia yielded a rich Middle (MP) and Late Pleistocene some of the non-metrical and metrical characteristics used to (LP) fossil record documenting the evolution of the Neandertals determine the Neandertal phenotype were already observed in that can be analyzed in light of recently acquired paleogenetical Europe during the MP (2). The discovery of the extensive MP data, an abundance of archeological evidence, and a well-known series of Sima de los Huesos (SH) (Atapuerca, Spain) (3) environmental context. Their origin likely relates to an episode of confirmed the long evolutionary history of this Western recolonization of Western Eurasia by hominins of African origin Eurasian lineage. However, debate continues over its exact carrying the Acheulean technology into Europe around 600 ka. An date of differentiation as well as over various phylogenetic and enhancement of both glacial and interglacial phases may have taxonomic implications. played a crucial role in this event, as well as in the subsequent evolutionary history of the Western Eurasian populations. In ad- Neandertals as a Sister Group dition to climatic adaptations and an increase in encephalization, Neandertals lived in Western Eurasia below 55° N. latitude. genetic drift seems to have played a major role in their evolution. Significantly, although they were present South of Haifa To date, a clear speciation event is not documented, and the most (Israel), none have been documented in North Africa. -

Earliest Evidence of Modern Human Life History in North African Early Homo Sapiens

Earliest evidence of modern human life history in North African early Homo sapiens Tanya M. Smith*†, Paul Tafforeau‡§, Donald J. Reid¶, Rainer Gru¨ nʈ, Stephen Egginsʈ, Mohamed Boutakiout**, and Jean-Jacques Hublin* *Department of Human Evolution, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Deutscher Platz 6, D-04103 Leipzig, Germany; ‡Laboratoire de Ge´obiologie, Biochronologie et Pale´ontologie Humaine, Unite´Mixte de Recherche 6046, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Universite´de Poitiers, 40 Avenue du Recteur Pineau, 86022 Poitiers Cedex, France; §European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, 6 rue Jules Horowitz, BP 220, 38046 Grenoble Cedex, France; ¶Department of Oral Biology, School of Dental Sciences, Newcastle University, Framlington Place, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 4BW, United Kingdom; ʈResearch School of Earth Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200, Australia; and **Department of Geology, Faculty of Sciences, University Mohammed V-Agdal, Avenue Ibn Battouta, BP 1014, Rabat, Morocco Communicated by Richard G. Klein, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, February 1, 2007 (received for review December 12, 2006) Recent developmental studies demonstrate that early fossil homi- but similar rates of root extension; this was interpreted as nins possessed shorter growth periods than living humans, imply- evidence that life history was similar between Neanderthals and ing disparate life histories. Analyses of incremental features in modern humans (13). However, overlap in molar crown forma- teeth provide an accurate means of assessing the age at death of tion times and root extension rates have been found between developing dentitions, facilitating direct comparisons with fossil chimpanzees and humans (10, 14), despite differences in life and modern humans. It is currently unknown when and where the history scheduling. -

Paper Series N° 33

33 World Heritage papers Human origin sites and the Heritage World in Africa Convention 33 World Heritage papers HEADWORLD HERITAGES 2 Human origin sites and the World Heritage Convention in Africa For more information contact: UNESCO World Heritage Centre papers 7, place Fontenoy 75352 Paris 07 SP France Tel: 33 (0)1 45 68 18 76 Fax: 33 (0)1 45 68 55 70 E-mail: [email protected] http://whc.unesco.org World HeritageWorld Human origin sites and the World Heritage Convention in Africa Nuria Sanz, Editor Coordinator of the World Heritage/HEADS Programme Table of Contents Published in 2012 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Foreword Page 6 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France Kishore Rao, Director, UNESCO World Heritage Centre © UNESCO 2012 Foreword Page 7 All rights reserved H.E. Amin Abdulkadir, Minister, Ministry of Culture and Tourism Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia ISBN 978-92-3-001081-2 Introduction Page 8 Original title: Human origin sites and the World Heritage Convention in Africa Published in 2012 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Coordination of the HEADS Programme, UNESCO World Heritage Centre The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Outstanding Universal Value of human evolution in Africa Page 13 Yves Coppens The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. -

An Archaic Character in the Broken Hill Innominate E. 719

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 71: 115-120 (1986) An Archaic Character in the Broken Hill Innominate E. 719 CHRISTOPHER B. STRINGER Department of Palaeontobgy, British Museum (Natural History), London S W7 5BD, England KEY WORDS Kabwe, Zambia; Homo erectus; Homo sapiens; Middle Pleistocene ABSTRACT The additional hominid material from Broken Hill, Kabwe, Zambia, is only dubiously associated with the hominid cranium from the site and is often considered to be anatomically modern in morphology. This study identifies an archaic feature, previously recognised in Pliocene and earlier Pleistocene innominates, in the Broken Hill innominate E. 719. An acetabulo- cristal buttress of cortical bone 10 mm thick is present, and this can be clearly distinguished from the morphology present in a comparative sample of large recent Homo sapiens innominates. This observation increases the likelihood that some of the additional specimens from Broken Hill are indeed of compa- rable antiquity to the hominid cranium and extends the range of hominids in which the feature has been recognised. From 1921 to 1925 a number of hominid (E. 689), distal left femur (E. 6891, and left fossils were recovered from a cave (subse- femoral diaphysis (E. 690), were recovered in quently destroyed) at the Broken Hill mine, various circumstances and must be consid- Kabwe, Zambia (Oakley et al., 1977). The ered unprovenanced (HrdliEka, 1930; Clark most important specimen, a well-preserved et al., 1968). Reconstructions of the stratig- cranium (BM[NH] registration No. E. 686), raphy of the Broken Hill cave and chemical became the holotype of Homo rhodesiensis analyses of the human bones suggested to Woodward 1921.