Voice of Truth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Egyptian Policy Toward Iran and the Challenges of Transition from Break up to Normalization

JOURNAL FOR IRANIAN STUDIES Specialized Studies A Peer-Reviewed Quarterly Periodical Journal Year 1. issue 4, Sep. 2017 ISSUED BY Arabian Gulf Centre for Iranian Studies Egyptian Policy toward Iran and the Challenges of Transition from Break Up to Normalization Mo’taz Salamah (Ph.D.) Head of the Arab and Regional Studies Unit and Director of the Arabian Gulf Program at the Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies Mohammad Saied Alsayyad Intellectual and Ideological Studies Researcher in the Arabian Gulf Center for Iranian Studies espite the news and calls of some Egyptian and Iranian personalities to restore relations between the two Dcountries, no significant development has been noticed in Egypt-Iran ties for about four decades. Some observers expected that the Iranian nuclear deal in 2015 would enhance rapprochement between Cairo and Tehran, but so far, no changes have been made, nor do signs indicate a normalization of relations between the two countries.(1) Journal for Iranian Studies 41 Diplomatic ties between Egypt and Iran have been severed since the Iranian revolution in 1979, the Camp David Accords, and process of establishing peace between Egypt and Israel. These relations deteriorated primarily due to Egypt’s hosting of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi– Iran’s former monarch – despite the new Iranian leaders’ demands that Egypt hands him over for trial. In addition, the Iranian leadership adopted a hard line against Cairo by naming one of Tehran’s main streets after Khalid Islambouli, who assassinated President Sadat in 1981 – and hosting a number of Egyptian Islamic groups that escaped trial in Egypt and took refuge in Iran.(2) Iran’s practices also included inciting the Egyptian people against their regime and even hosting terrorist groups that, until recently, the Iranian media called Muslim Rebels.(3) Egypt and Iran are two key powers in the region. -

Lamia Joreige a Brief History of Ouzaï

ﳌﻴﺎ ﺟﺮﻳﺞ، Lamia Joreige A Brief History of OuzaÏ Produced for the exhibition Under-Writing Beirut Marfa’ ©2017 A Brief History of OuzaÏ, 2017 Graphite pencil and inkjet print on paper 15 drawings, 40 x 30 cm Images based on photographs and documents from Assayad magazine, Elyssar, Ahmad Gharbieh, Lamia Joreige, Life Collection. Texts based on conversations with Firas Beydoun, Makram Beydoun, Wadah Charara, Elie Chedid, Farouk Dakdouki, Fadi Fawaz, Mustapha Nasser, Ramzieh Nasser, Salah Nasser, Zahed Clerc-Huybrechts, Wafa Charafeddine, Mona Fawaz, Mona Harb, Falk Jähnigen, Steven Judd, Mohammad Nokkari. professional actors, who were improvising and performing scenes inspired by their love affairs, professional lives, friendships and the places that are dear to them. The city and with their daily lives, I highlighted a malaise in present day-Beirut. One of the main characters of And the Living Is Easy is Firas Beydoun, who was born and lived then in Ouzaï, and whose grandfather, Ali Hassan Nasser, a pioneer, established his life and professional activities there, but also built a mosque, and a local leader (‘za3im’). As I pursued my project Under-Writing Beirut, I got interested in researching the history of Ouzaï, and met several members and acquaintances of the Nasser family. This piece, part of the project’s third chapter: Under-Writing these encounters as well as on the mundane and historic places that are enmeshed with the narratives of this area. Special Thanks to: Joumana Asseily, Firas Beydoun, Makram Beydoun, Wadah Charara, Sandra Dagher, Farouk Dakdouki, Ahmad Gharbieh, Ramzi Joreige, Cherine Karam, Mustapha Nasser, Ramzieh Nasser, Salah Nasser, Zahed Nasser, Anna Ogden-Smith, Lea Paulikevitch, Intisar Rabb, Ely Skaff, Scope Ateliers, Faysal Arabic Translation: Nisrine Nader اﻟﺘﻘﻴﺖ اﻟﻌﺪﻳﺪ ﻣﻦ اﻷﺷﺨﺎص واﳌﻌﺎرف ﻣﻦ آل ﻧﺎﴏ. -

Urbanization and the Changing Character of the Arab City

ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR WESTERN ASIA URBANIZATION AND THE CHANGING CHARACTER OF THE ARAB CITY United Nations Distr. GENERAL E/ESCWA/SDD/2005/1 19 April 2005 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR WESTERN ASIA URBANIZATION AND THE CHANGING CHARACTER OF THE ARAB CITY United Nations New York, 2005 Some references set forth in this paper were not submitted by the authors for verification. These references are reproduced in the form in which they were received. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Secretariat. 05-0247 Preface This publication sheds light on the role of development in shaping the character of the Arab city, with the aim of contributing to the discourse on urban development in the Arab region. It is divided into three parts, analysing the experience of three Arab cities, namely: Amman, Beirut and Dubai. Diligent effort and extensive cooperation has gone into preparing this publication. Special thanks are extended to the following: Mr. George Arbid, for drafting the case study of Beirut and the overall conclusion; Mr. Mohammad Al-Assad, for drafting the case study of Amman; Messrs. Hashim Sarkis and Nasser Abulhasan, for drafting the case study of Dubai; Mr. Riadh Tappuni, Leader of the Urban Development and Housing Policies Team, who led the effort in setting the thematic framework of this publication and supervised its preparation; and Ms. Nadine Chalak, research assistant, who reviewed the publication and worked on its layout. c d Executive summary As a contribution to the discourse on urban development, this study is aimed at analysing the changes that the Arab cities have undergone and are still undergoing as a result of such major forces as rural-urban migration, population growth and socio-economic developments, taking into consideration the historical background of the city and its social capital. -

Bank Audi Interim Report March 2021

BANK AUDI INTERIM REPORT JUNE 2021 1 BANK AUDI INTERIM REPORT JUNE 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION 03 ADDRESSES 75 AND ANALYSIS 5 1.0. LEBANON 76 Bank Audi sal 76 1.0. BASIS OF PRESENTATION 6 SOLIFAC sal 78 2.0. OPERATING ENVIRONMENT 6 2.0. TURKEY 78 3.0. CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL CONDITION 7 Odea Bank A.Ş. 78 3.1. ASSET ALLOCATION 9 3.0. CYPRUS 79 3.2. FUNDING SOURCES 16 BAPB Holding Limited 79 3.3. GROUP RESULTS OF OPERATIONS 19 4.0. SWITZERLAND 79 Banque Audi (Suisse) SA 79 5.0. SAUDI ARABIA 79 Audi Capital (KSA) cjsc 79 60. QATAR 79 Bank Audi LLC 79 7.0. FRANCE 79 Bank Audi France sa 79 8.0. UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 79 Bank Audi sal Representative Office 79 02 INTERIM CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS (UNAUDITED) 23 INTERIM CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED INCOME STATEMENT 26 INTERIM CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME 27 INTERIM CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 28 INTERIM CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CASH FLOW 29 INTERIM CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 30 NOTES TO THE INTERIM CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 32 Notes’ Index 33 Notes 34 3 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS (UNAUDITED) BANK AUDI INTERIM REPORT JUNE 2021 01 MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION & ANALYSIS 4 5 MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION & ANALYSIS BANK AUDI INTERIM REPORT JUNE 2021 1.0. BASIS OF PRESENTATION The evolution of real sector indicators this year is actually a mirror image an average of USD 93 per household per month for 500 thousand eligible of a sluggish economy. The BdL average coincident indicator, a weighted households, parallel to potential subsidy rationalisation. -

Lebanon 2020

LEBANON 2020 LEBANON BESHARA EL-KHOURY Banna & Sayrawan Bldg., Bank Audi sal Beshara El-Khoury Street. Tel: (961-1) 664093. Fax: (961-1) 664096. Member of the Association of Banks in Lebanon Capital: LBP 992,879,819,050 BLISS (as at December 2020) Kanater Bldg., Bliss Street. Consolidated shareholders’ equity: Tel: (961-1) 361793. Fax: (961-1) 361796. LBP 4,448,419,828,889 (as at December 2020) GEFINOR C.R. 11347 Beirut Gefinor Center, Clemenceau Street. List of Banks No. 56 Tel: (961-1) 743400. Fax: (961-1) 743412. HEADQUARTERS HAMRA Bank Audi Plaza, Bab Idriss. Mroueh Bldg., Hamra Street. P.O. Box 11-2560 Beirut - Lebanon Tel: (961-1) 341491. Fax: (961-1) 344680. Tel: (961-1) 994000. Fax: (961-1) 990555. Customer helpline: (961-1) 212120. JNAH Swift: AUDBLBBX. Tahseen Khayat Bldg., Khalil Moutran Street. [email protected] bankaudigroup.com Tel: (961-1) 844870. Fax: (961-1) 844875. BRANCHES MAZRAA Wakf El-Roum Bldg., Saeb Salam Blvd. CORPORATE BRANCHES Tel: (961-1) 305612. ASHRAFIEH – MAIN BRANCH Fax: (961-1) 316873, 300451. SOFIL Center, Charles Malek Avenue. Tel: (961-1) 200250. MOUSSEITBEH Fax: (961-1) 200724, 339092. Makassed Commercial Center, Mar Elias Street. BAB IDRISS Tel: (961-1) 818277. Fax: (961-1) 303084. Bank Audi Plaza, Omar Daouk Street. Tel: (961-1) 977588. SELIM SALAM Fax: (961-1) 999410, 971502. Sharkawi Bldg., Selim Salam Avenue. Tel: (961-1) 318824. Fax: (961-1) 318657. VERDUN Verdun 2000 Center, Rashid Karameh Avenue. SERAIL Tel: (961-1) 805805. Bank Audi Plaza, Omar Daouk Street. Fax: (961-1) 865635, 861885. Tel: (961-1) 952515. -

Revisiting Urban Planning in the Middle East North Africa Region

Revisiting Urban Planning in the Middle East North Africa Region Dr. Mostafa Madbouly Regional study prepared for Revisiting Urban Planning: Global Report on Human Settlements 2009 Available from http://www.unhabitat.org/grhs/2009 Dr. Madbouly is a professor of urban planning and management at the Housing and Building National Research Center, Cairo, Egypt. For seven years, he has been involved in running training programs on urban planning and management for local and international officials and professionals. Dr. Madbouly has worked with several international organizations as a local and international consultant in the field of urban planning, housing and slum upgrading. He has published a series of urban planning papers in those fields in several international and national conferences and Journals. Disclaimer: This case study is published as submitted by the consultant, and it has not been edited by the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the Governing Council of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme or its Member States. Acknowledgements The author gratefully acknowledges the help of Dr. Ayman El-Hefnawi and Dr. Maha Fahim in the research and writing of this report. -

Cesar Nasr Collection, 1950-2013 a Finding Aid to the Collection in the University Libraries, AUB Prepared by Dalya Nouh

Archives and Special Collections Department, American University of Beirut Beirut, Lebanon © 2018 Cesar Nasr Collection, 1950-2013 A Finding Aid to the Collection in the University Libraries, AUB Prepared by Dalya Nouh Contact information: [email protected] Webpage: www.aub.edu.lb/Libraries/asc Descriptive Summary Call No.: 363.7 Bib record: b22065404 Record Creator: Nasr, Cesar. Collection Title: Cesar Nasr Collection, 1950-2013. Collection Dates: 1950-2013 Physical Description: around 3 linear feet (7 boxes) Language(s): French, Arabic Administrative Information Source: The collection was donated to the AUB Libraries by Dr. Cesar Nasr, in July 2013. Access Restrictions: The collection can be used within the premises of the Archives and Special Collections Department, Jafet Memorial Library, American University of Beirut. Photocopying Restriction: No photocopying restriction except for fragile material. Preferred Citation: Cesar Nasr Collection, 1950-2013, 363.7 Box no.- , File no.-, American University of Beirut/Library Archives. Compiled by: Dalya Nouh and Yasmine Younes. Scope and Content This collection includes published books, personal papers and archival materials by the late Dr. Cesar Nasr, the founder of the Lebanese Ministry of Environment (MOE) and its Minister from 1980 to 1982. The donation includes many of his published books, correspondence with prominent figures, press clippings and documents related to his research and his accomplishments in the field of environment and nature conservation. The collection was donated to the AUB Libraries in July 2013 by Dr. Nasr and his wife. It is of relevance to researchers interested in climate change, nature conservation, social sciences and politics in the region. -

Chabaka2015.Pdf

ACHABAKA Desirable, Elegant and Witty Energic, sensational, and vibrating with attraction and elegance, Achabaka caters for a trendy and affluent readership throughout the Arab world. Backed by Dar Assayad’s 72 years journalistic experience, a young, aggressive and talented team of editors, reporters and layout artists, have been working for a year to refashion the best selling magazine in the Arab world. Achabaka‘s editorial style and layout are designed to strengthen its entertainment value to readers. Indeed, added to the famed Achabaka columns are an extended section on the private lives of Arab and international celebrities, gossip columns, beauty, style and fitness pages, a new and improved agony aunt column, more social scene pages, and weekly serialized stories and biographies. Achabaka is determined to extend its lead among publications in the Arab world by providing its readers with an unrivalled quality of writing and a moving yet peaceful visual experience. Since its inception in 1956, Achabaka has remained the leading and most audacious Arab magazine. Its success stems from its power to adapt itself to successive generations of readers, who have always chosen it as a guide to their tastes in music and entertainment. Achabaka is a rewarding platform for advertisers who not only wish to grab the attention of a large and affluent number of readers in the Middle East, but who also want to inspire their tastes, hearts and minds. ACHABAKA Energic, sensational, and vibrating with attraction and elegance Circulation 2014 Lebanon 35,817 Syria - Kuwait 6,006 Jordan 7,082 UAE 9,018 Sub Total 42,899 Bahrain 3,914 Egypt 5,800 Qatar 3,805 Other Arab countries 29,778 Oman 3,260 Europe and R o W 8,619 Yemen 2,627 Sub Total 44,197 Iraq 5,025 Sub Total 33,655 Average weekly sales Total 120,751 Source: DAS Reasearch Dept. -

Abstractbook.Pdf

Abstract Book THE 2nd INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF ADVANCED COMPUTING AND INFORMATICS (ICACIN 2021) May 24-25, 2021 Casablanca, Morocco Advances on Smart Computing and Informatics Editors: Faisal Saeed Tawfik Al-Hadhrami Errais Mohammed Mohammed AlSarem Organizing Committee Honorary Chair Saddiqi Omar Dean of the Faculty of science, Ain Chock, Hassan II University Casablanca, Morocco International Advisory Board Naomie Salim Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia Rose Alinda Alias Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia Ahmad Lotfi, Nottingham Trent University, UK Funminiyi Olajide Nottingham Trent University, UK Fahad Ghabban Taibah University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Muhannad Al-Muhaimeed Taibah University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Mohammed Alshargabi Najran University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Conference General Chair Errais Mohammed Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco Faisal Saeed President, Yemeni Scientists Research Group (YSRG) Head of Data Science Research Group in Taibah University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Program Committee Co-Chairs Mohamed Lahby Hassan II University - Casablanca, Morocco Raouyane Brahim, Hassan II University – Casablanca Morocco Mohammed Al-Sarem Taibah University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Publications Committee Tawfik Al-Hadhrami Nottingham Trent University, UK ii Organizing Committee Publicity Committee Mandar Meriem National School of Applied Science of Berre- chid – Morocco IT Committee Koulali Rim Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco Chbihi Louhdi Mohammed Réda Hassan II University, Casablanca, -

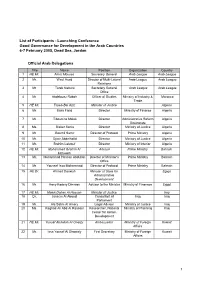

Final List of Participants 6-7 Feb 05

List of Participants - Launching Conference Good Governance for Development in the Arab Countries 6-7 February 2005, Dead Sea, Jordan Official Arab Delegations Title Name Position Organization Country 1 HE Mr. Amro Moussa Secretary General Arab League Arab League 2 Mr. Wael Asad Director of Multi-Lateral Arab League Arab League Relations 3 Mr. Tarek Nabulsi Secretary General Arab League Arab League Office 4 Mr. Abdelazez Rabah Officer of Studies Ministry of Industry & Morocco Trade 5 HE Mr. Tayeb Bel Aziz Minister of Justice Algeria 6 Mr. Baka Farid Director Ministry of Finance Algeria 7 Mr. Tiboutrine Malek Director Administrative Reform Algeria Directorate 8 Ms. Bisker Sonia Director Ministry of Justice Algeria 9 Mr. Bourhil Samir Director of Protocol Prime Ministry Algeria 10 Mr. Djarir Abdelhafid Director Ministry of Justice Algeria 11 Mr. Brahim Lakrouf Director Ministry of Interior Algeria 12 HE Mr. Mohammad Ibrahim Al Advisor Prime Ministry Bahrain Motaweh 13 Mr. Mohammad Hassan Abdullah Director of Minister's Prime Ministry Bahrain Office 14 Mr. Youssef Issa Mohammad Director of Protocol Prime Ministry Bahrain 15 HE Dr. Ahmad Darwish Minister of State for Egypt Administrative Development 16 Mr. Hany Kadery Dimnian Advisor to the Minister Ministry of Finanace Egypt 17 HE Mr. Malek Dahan Al Hassan Minister of Justice Iraq 18 Dr. Jassem Al Aboudi Consultant of Iraq Iraq Parliament 19 Mr. Ala Salim Al Amery Legal Advisor Ministry of Justice Iraq 20 Ms. Raghad Ali Abd Al Rassoul Researcher, National Ministry of Planning Iraq Center for Admin. Development 21 HE Mr. Yousef Abdullah Al Onaizy Ambassador Ministry of Foreign Kuwait Affairs 22 Mr. -

Facts and Figures

LEBANON FACTS AND FIGURES 2018 Geography Surface (in sqkm) 10,452 Coast length (in km) 210 Maximum altitude: Qornet-El-Saouda (in m) 3,083 Mount Lebanon average altitude (in m) 2,200 Average temperature (in centigrade) 20.4 Average coastal rainfall (in mm per year) 893 Number of rainy days per year 78 Humidity rate 68% Demography Population (in millions) 6.09 Population growth rate (2008-2018) 4.0% Population density (per sqkm) 583 Urban population/Total population 88% Active labor force (in millions) 2.23 Life expectancy at birth 80 Infant mortality rate (per 1,000 live births) 7 Human Development Index (UNDP) 0.76 Education Adult literacy rate Male 94% Female 88% Net enrollment ratio (primary) Male (% of primary school-age children) 97% Female (% of primary school-age children) 97% Technology Diffusion Number of telephone mainlines (per 100 people) 14.9 Number of cellular subscribers (per 100 people) 72.3 Number of internet users (per 100 people) 78.2 Number of broadband subscribers (per 100 people) 21.6 Infrastructure Roads (paved): 6,970 km Railways: non functional Airport: Rafic Hariri International Airport (16 km from city center) Ports: Beirut (principal), Tripoli (main port for the North), Jounieh, and Saida (main port for the South) General Currency: Lebanese Pound Official language: Arabic, French and English are widely spoken Business Hours Government: 7:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. Monday to Thursday 7:30 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. Friday Banks' counters: 8:30 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. Monday to Friday 8:30 a.m. -

Political Rationality and Irrationality: the Case of the Lebanese Forces

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Political Rationality and Irrationality: The aC se of the Lebanese Forces. Leila El-tawil Sarieddine Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sarieddine, Leila El-tawil, "Political Rationality and Irrationality: The asC e of the Lebanese Forces." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5021. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5021 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.