Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forbidden Songs of the Pgaz K'nyau

Forbidden Songs of the Pgaz K’Nyau Suwichan Phattanaphraiwan (“Chi”) / Bodhivijjalaya College (Srinakharinwirot University), Tak, Thailand Translated by Benjamin Fairfield in consultation with Dr. Yuphaphann Hoonchamlong / University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Honolulu, Hawai‘i Peer Reviewer: Amporn Jirattikorn / Chiang Mai University, Thailand Manuscript Editor and General Editor: Richard K. Wolf / Harvard University Editorial Assistant: Kelly Bosworth / Indiana University Bloomington Abstract The “forbidden” songs of the Pkaz K’Nyau (Karen), part of a larger oral tradition (called tha), are on the decline due to lowland Thai moderniZation campaigns, internaliZed Baptist missionary attitudes, and the taboo nature of the music itself. Traditionally only heard at funerals and deeply intertwined with the spiritual world, these 7-syllable, 2-stanza poetic couplets housing vast repositories of oral tradition and knowledge have become increasingly feared, banned, and nearly forgotten among Karen populations in Thailand. With the disappearance of the music comes a loss of cosmology, ecological sustainability, and cultural knowledge and identity. Forbidden Songs is an autoethnographic work by Chi Suwichan Phattanaphraiwan, himself an artist and composer working to revive the music’s place in Karen society, that offers an inside glimpse into the many ways in which Karen tradition is regulated, barred, enforced, reworked, interpreted, and denounced. This informative account, rich in ethnographic data, speaks to the multivalent responses to internal and external factors driving moderniZation in an indigenous and stateless community in northern Thailand. Citation: Phattanaphraiwan, Suwichan (“Chi”). Forbidden Songs of the Pgaz K’Nyau. Translated by Benjamin Fairfield. Ethnomusicology Translations, no. 8. Bloomington, IN: Society for Ethnomusicology, 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14434/emt.v0i8.25921 Originally published in Thai as เพลงต้องห้ามของปกาเกอะญอ. -

Recent Arrests List

ƒ ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 8 of the Export and Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Lin of Special Branch President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s S: 25 of the Natural Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Naing law President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and parliament President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Speaker of the Union Assembly, the Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD 5 (U) T Khun Myat M Joint House and Pyithu Hluttaw, the 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and lower house of the Myanmar President U Win Myint were detained. -

Performance Program

Dance Visions 2020 Choreography by Lar Lubovitch UCI Claire Trevor School of the Arts Photo by Rose Eichenbaum DANCE VISIONS 2021 Artistic Directors Molly Lynch and Tong Wang February 25-27, 2021 8:00 p.m. PST University of California, Irvine Dr. Stephen Barker, Dean | Claire Trevor School of the Arts ARTISTIC DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE On behalf of the UCI Claire Trevor School of the Arts — Department of Dance, we are delighted to welcome you to our virtual production of “Dance Visions 2021!” Despite the many challenges this year, the creative process between choreographers and dancers allows for many interesting and diverse ideas to be expressed through movement. The outstanding choreographers included in this performance are professors Lindsay Gilmour, Chad Michael Hall, Ariyan Johnson, Vitor Luiz, Molly Lynch, Lisa Naugle, S. Ama Wray in collaboration with Alan Terricciano, and Distinguished Professor Lar Lubovitch. This production would not be possible without the joint effort of our highly regarded colleagues in the Department of Drama — Design and Stage Management Programs. Their talent and commitment help bring the artists’ visions to fruition. Together, the Dance Visions artistic team continues our tradition of excellence in dance, keeping the UCI Dance department at the forefront of education and performance both nationally and internationally. We would also like to thank all the Department of Dance donors. We are grateful for the many scholarships that are awarded to our students and support for the dance productions. It is extremely important for our dancers! We are all deeply saddened by the passing of one of our major supporters, Mr. -

ICTM Abstracts Final2

ABSTRACTS FOR THE 45th ICTM WORLD CONFERENCE BANGKOK, 11–17 JULY 2019 THURSDAY, 11 JULY 2019 IA KEYNOTE ADDRESS Jarernchai Chonpairot (Mahasarakham UnIversIty). Transborder TheorIes and ParadIgms In EthnomusIcological StudIes of Folk MusIc: VIsIons for Mo Lam in Mainland Southeast Asia ThIs talk explores the nature and IdentIty of tradItIonal musIc, prIncIpally khaen musIc and lam performIng arts In northeastern ThaIland (Isan) and Laos. Mo lam refers to an expert of lam singIng who Is routInely accompanIed by a mo khaen, a skIlled player of the bamboo panpIpe. DurIng 1972 and 1973, Dr. ChonpaIrot conducted fIeld studIes on Mo lam in northeast Thailand and Laos with Dr. Terry E. Miller. For many generatIons, LaotIan and Thai villagers have crossed the natIonal border constItuted by the Mekong RIver to visit relatIves and to partIcipate In regular festivals. However, ChonpaIrot and Miller’s fieldwork took place durIng the fInal stages of the VIetnam War which had begun more than a decade earlIer. DurIng theIr fIeldwork they collected cassette recordings of lam singIng from LaotIan radIo statIons In VIentIane and Savannakhet. ChonpaIrot also conducted fieldwork among Laotian artists living in Thai refugee camps. After the VIetnam War ended, many more Laotians who had worked for the AmerIcans fled to ThaI refugee camps. ChonpaIrot delIneated Mo lam regIonal melodIes coupled to specIfic IdentItIes In each locality of the music’s origin. He chose Lam Khon Savan from southern Laos for hIs dIssertation topIc, and also collected data from senIor Laotian mo lam tradItion-bearers then resIdent In the United States and France. These became his main informants. -

Myanmar Update August 2018 Report

STATUS OF HUMAN RIGHTS & SANCTIONS IN MYANMAR AUGUST 2018 REPORT Summary. This report reviews the August 2018 developments relating to human rights in Myanmar. Relatedly, it addresses the interchange between Myanmar’s reform efforts and the responses of the international community. I. Political Developments......................................................................................................2 A. Rohingya Refugee Crisis................................................................................................2 B. Corruption.......................................................................................................................3 C. International Community / Sanctions...........................................................................4 II. Civil and Political Rights...................................................................................................5 A. Freedom of Speech, Assembly and Association............................................................5 B. Freedom of the Press and Censorship...........................................................................7 III. Economic Development.....................................................................................................8 A. Economic Development—Legal Framework, Foreign Investment............................8 B. Economic Development—Infrastructure, Major Projects..........................................8 IV. Peace Talks and Ethnic Violence....................................................................................11 -

Lonetree Convicted Cargo Given 30 Year Imprisonment

Vol. 16. No. 35 Serving MCAS Kaneohe Bay.. 1st NIAB C um) II. NI Smith 11;1 Marine liarrin II:mail August 27, 19147 Doi) Lonetree convicted cargo Given 30 year imprisonment. `hostage' Sergeant. Clayton Lonetree becanni the $5,000, reduced to private and rind did first Marine ever convicted of espionage dishonorable discharge The conviction Washington, - The as a result of his Aug. 24 general court - carried a possible life sentence. Military Sea lift Command martial at (r)uantico, VA. MSC) is will-king with the A jury of eight Marine officers delibel n of Justice to According to a M(II)EC, Qua nticii ated for nearly three hours before set-den' on nla am a court order requiring spokesman, Lonetree was convicted I3 ing Lonetree. ' S lines to release DoD specifications of espionage and conspir- argo destined for Hawaii acy h. commit espionage. These allega- Lieutenant General Frank Petersen Jr., and Guam. Both agencies tions -rimmed from his involvement with commanding general, Mt '11E1' Quantico, have been in negotiation foreign nationals in Moscow. Va., is currently reviewing the case. Alter with U.S. Lines bankruptcy IA( len Peterson eon deervuse attorneys for release of the A termer Marine security guard at the his review but he cannot carlja. dale. these negoti S holuissy in Moscow, Lonetree was the sentence if he elviose,, idioms have not been success- sem (-need to 30 years in prison, fined increase it. ful for this cargo, some of which is already in the ports of Honolulu, Guam and on the U.S. -

2015 Program

SPRING COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN May 2, 2015 10:00 a.m. This program includes a list of the candidates for degrees to be granted upon completion of formal requirements. Candidates for graduate degrees are recommended jointly by the Executive Board of the Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies and the faculty of the school or college awarding the degree. Following the School of Graduate Studies, schools are listed in order of their founding. Candidates within those schools are listed by degree then by specialization, if applicable. Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies .................................................................................................. 21 College of Literature, Science, and the Arts ............................................................................................................33 Medical School ...................................................................................................................................................... 54 Law School ............................................................................................................................................................ 55 School of Dentistry ................................................................................................................................................ 57 College of Pharmacy .............................................................................................................................................. 59 College of Engineering .......................................................................................................................................... -

Welkom Willkommen Venuti Пожаловать Добро Velkommen Bienvenidos

Witamy dobro welcome pozalowat ορίσατε kαλώς kαλώς boas hoş geldiniz hoş tervetuloa vindas ben welkom willkommen venuti пожаловать Добро velkommen bienvenidos bienvenue Salvete we. luebeck. INTERCULTURALlūdzam Laipni SUMMER Mai 20th – Juli 23rd 2017 A cooperation project between VHS Luebeck and many partners Witamy dobro welcome pozalowat ορίσατε kαλώς kαλώς boas hoş geldiniz hoş tervetuloa we. luebeck. INTERCULTURAL SUMMER 2017 vindas ben welkom willkommen venuti пожаловать Добро velkommen bienvenidos bienvenue Salvete Laipni lūdzam Laipni Pictogramms of the Intercultural Summer 2017 All events in this brochure are in chronological order. The following pictogramms give you a quick overview of topic, target group, and event form. Topics Target group Children Nature & environment Young people Helath, medicine sports Dear Citizen and Visitors of Luebeck! Adults Luebeck is moving forward! This year will be the third time the citizens of Luebeck will Economy & technology show how wonderful interacting with people from the most extraordinary walks of life All ages and backgrounds from uncountable regions of the world can be. Under the motto “we. luebeck.” we cordially invite you to our third intercultural summer. Arts & music Special target groups The hallmark of the intercultural summer in Luebeck is its pinpoint focus on the direct interaction between people. In this way low-threshold opportunities are offered to meet Literature & drama and to experience new things, and we all have the opportunity to get to know each other. By learning new traditions we also start to reflect on our own. I find it thrilling and enriching Society, philosphy & politics Event form to witness this exchange. Speeches & discussions Once more our organizers in Luebeck offer wonderful opportunities to experience the Archeology & history diversity of cultures. -

Buddhism and Nonviolent Global Problem-Solving

Buddhism and Nonviolent Global Problem-Solving Ulan Bator Explorations BUDDHISM AND NONVIOLENT GLOBAL PROBLEM-SOLVING Ulan Bator Explorations Edited by Glenn D. Paige and Sarah Gilliatt Center for Global Nonviolence 2001 Copyright ©1991 by the Center for Global Nonviolence Planning Project, Spark M. Matsunaga Institute for Peace, University of Hawai'i, Honolulu, Hawai'i, 96822. Copyright ©1999 by the nonprofit Center for Global Nonviolence, Inc., 3653 Tantalus Drive, Honolulu, Hawai'i, 96822-5033. Website: www.globalnonviolence.org. Email: [email protected]. Copying for personal and educational use is encouraged by the copyright holders. Original publication was made possible by the generosity of the Korean Buddhist Dae Won Sa Temple of Hawai'i. Now Mu-Ryang-Sa (Broken Ridge Buddhist Temple), 2408 Halelaau Place, Honolulu, Hawai'i, 96816. By gentle and skillful means based on reason. --From the Mongolian Buddhist tradition CONTENTS Preface Introduction 1 OPENING ADDRESS From Violent Combat to Playful Exchange of Flowers Khambo Lama Kh. Gaadan 7 PERSPECTIVES: BUDDHISM, LEADERSHIP, SCHOLARSHIP, ACTION Global Problem-Solving: A Buddhist Perspective Sulak Sivaraksa 15 The United Nations, Religion, and Global Problems: Facing a Crisis of Civilization Kinhide Mushakoji 33 Visioning a Peaceful World Johan Galtung 37 Nonviolent Buddhist Problem-Solving in Sri Lanka A.T. Ariyaratne 65 GLOBAL PROBLEM-SOLVING Five Principles for a New Global Moral Order Thich Minh Chau 91 The Importance of the Buddhist concept of Karma for World Peace Yoichi Kawada 103 Disarmament Efforts from the Standpoint of Mahayana Buddhism Yoichi Shikano 115 Buddhism and Global Economic Justice Medagoda Sumanatissa 125 "buddhism" and Tolerance for Diversity of Religion and Belief Sulak Sivaraksa 137 Nonviolent Ecology: The Possibilities of Buddhism Leslie E. -

[email protected] Providing Details, and We Will Remove Access to the Work Immediately and Investigate Your Claim

Roskilde University "We are Like Water in Their Hands" Experiences of imprisonment in Myanmar Gaborit, Liv Stoltze Publication date: 2020 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Gaborit, L. S. (2020). "We are Like Water in Their Hands": Experiences of imprisonment in Myanmar. Roskilde Universitet. FS & P Ph.D. afhandlinger General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 “We are Like Water in Their Hands” – experiences of imprisonment in Myanmar Liv Stoltze Gaborit Supervisor: Bjørn Thomassen (RUC) Co-supervisor: Andrew M. Jefferson (DIGNITY) ISSN no. 0909-9174 PhD Programme: International Studies Department of Social Sciences and Business Roskilde University 2020 Front page: Ponsan Tain painted by artist Htein Lin in Oh Boh Prison in 2002. © Htein Lin. In collaboration with DIGNITY – Danish Institute Against Torture Funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark Note on authorship: While the front page of this dissertation only lists one name, significant contributions have been made by several people. -

Scriptural Continuity Between Traditional and Engaged Buddhism

SCRIPTURAL CONTINUITY BETWEEN TRADITIONAL AND ENGAGED BUDDHISM Jack Carman B.A., California State University, Fresno 1974 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in LIBERAL ARTS at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2010 © 2010 Jack Carman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii SCRIPTURAL CONTINUITY BETWEEN TRADITIONAL AND ENGAGED BUDDHISM A Thesis by Jack Carman Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Joel Dubois, Ph.D. __________________________________, Second Reader Jeffrey Brodd, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date iii Student: Jack Carman I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Department Chair ___________________ Jeffrey Brodd, Ph.D. Date Liberal Arts Master’s Program iv Abstract of SCRIPTURAL CONTINUITY BETWEEN TRADITIONAL AND ENGAGED BUDDHISM by Jack Carman Engaged Buddhism is a modern reformist movement. It stirs debate concerning the scriptural and philosophical origins of Buddhist social activism. Some scholars argue there is continuity between traditional Buddhism and a rationale for social activism in engaged Buddhism. Other scholars argue that while the origins of social activism may be latent in the traditional scriptures, this latency cannot be activated until Asian Buddhism interacts with Western sociopolitical theory. In this thesis I present an overview of Buddhist fundamentals that are common to both traditional and engaged Buddhism, and I conduct a critical overview of three seminal Buddhist texts – The Dhammapada, The Edicts of Asoka, and Nagarjuna’s Precious Garland. I provide critical reviews of contemporary Buddhist scholars representing both the traditional and modernist schools. -

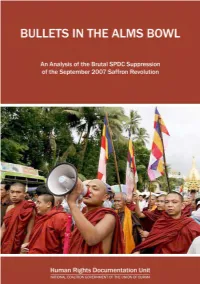

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike.