4024 TRANS SPACES-A/Rev/Jr 4/3/04 10:27 Am Page 78

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Jullundur, Part X-A & B

,CENSUS 1971 PARTS X-A" II VILLAGE & TOWN SERIES 17 DIRECTORY PUNJAB VILLAGE & TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENS'US ABSTRACT DISTRICT JULLUN'DUR CENSUS DISTRICT HANDBOOK P. L. SONDHI H. S. KWATRA ". OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE OF THE PfJ'NJAB CIVIL SERVIce Ex-officio Director of Census OperatiONl Deputy Director (~l Cpnsus Operations ', .. PUNJAB PUNJAB' Modf:- Julluodur - made Sports Goods For 01 ympics ·-1976 llvckey al fhe Montreal Olympics. 1976, will be played with halls manufactured in at Jullundur. Jullundur has nearly 350 sports goods 111l1nl~ractur;l1g units of various sizes. These small units eXJlort tennis and badminton rackets, shuttlecocks and several types of balls including cricket balls. Tlte nucleu.s (~( this industry was formed h,J/ skilled and semi-skilled workers who came to 1ndia a/It?r Partition. Since they could not afford 10 go far away and were lodged in the two refugee can'lps located on the outskirts of .IuJ/undur city in an underdeveloped area, the availabi lity of the sk illed work crs attracted the sport,\' goods I1zCllllljacturers especiallY.from Sialkot which ,was the centre (~f sports hJdustry heji,)re Partition. Over 2,000 people are tU preSt'nt employed in this industry. Started /roln scratch after ,Partilion, the indLlstry now exports goods worth nearly Rs. 5 crore per year to tire Asian and European ("'omnu)fzwealth countril's, the lasl being our higgest ilnporters. Alot(( by :-- 1. S. Gin 1 PUNJAB DISTRICT JULLUNDUR kflOMlTR£S 5 0 5 12_ Ie 20 , .. ,::::::;=::::::::;::::_:::.:::~r::::_ 4SN .- .., I ... 0 ~ 8 12 MtLEI "'5 H s / I 30 3~, c ! I I I I ! JULLUNOUR I (t CITY '" I :lI:'" I ,~ VI .1 ..,[-<1 j ~l~ ~, oj .'1 i ;;1 ~ "(,. -

Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF)

Public Disclosure Authorized PUNJAB MUNICIPAL SERVICES IMPROVEMENT PROJECT (PMSIP) Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Draft April 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: Punjab Municipal Infrastructure Development Company, Department of Local Government, Government of Punjab Public Disclosure Authorized i TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................... VI CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 13 1.1 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................ 13 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE ESMF .................................................................................................................................. 13 1.3 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................ 13 CHAPTER 2: PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................... 15 2.1 PROJECT COMPONENTS .................................................................................................................................... 15 2.2 PROJECT COMPONENTS AND IMPACTS................................................................................................................ -

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administr Ative Detail of Repair Approval Name of Name Xen/Mobile No

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administr ative Detail of Repair Approval Name of Name Xen/Mobile No. Sr. No. Distt. MC Name of Work Strengthe Premix Contractor/Agency Name of SDO/Mobile No. Length Cost Raising ning Carepet in in Km. in lacs in Km in Km Km 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 PARTAPPURA TO DERA SEN BHAGAT M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 1 Jalandhar Bilga 2.4 15.06 0 0 2.4 (16 ft wide) (1.50 km length) Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 MAO SAHIB TO DHUSI BANDH (KHERA M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 2 Jalandhar Bilga 4.24 40.31 0 2.44 4.24 BET)VIA KULIAN TEHAL SINGH Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 MAU SAHIB TO RURKA KALAN VIA M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 3 Jalandhar Bilga PARTABPURA MEHSAMPUR (13.15= 21.04 128.57 0.31 0.82 21.04 Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 16' wide) PHIRNI PIND MAOSAHIB TO MAOSAHIB M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 4 Jalandhar Bilga 0.8 7.75 0 0.435 0.8 DHUSI BAND ROAD Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 PHILLAUR RURKA KALAN TO RURKA Sh. Rakesh Kumar Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 5 Jalandhar Bilga 3.35 31.06 0 1.805 3.35 KALAN MAU SAHIB ROAD Contractor Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 PHILLAUR NURMAHAL ROAD TO Sh. Rakesh Kumar Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 6 Jalandhar Bilga 3.1 24.27 0 1.015 3.1 PRATABPURA VIA SANGATPUR Contractor Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 Sh. -

Roll Number.Pdf

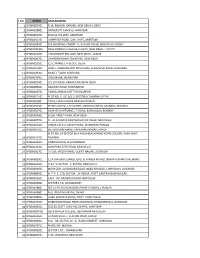

POST APPLIED FOR :- PEON Roll No. Application No. Name Father’s Name/ Husband’s Name Permanent Address 1 284 Aakash Subash Chander Hno 241/2 Mohalla Nangal Kotli Mandi Gurdaspur 2 792 Aakash Gill Tarsem lal Village Abulkhair Jail Road, Gurdaspur 3 1171 Aakash Masih Joginder Masih Village Chuggewal 4 1014 Aakashdeep Wazir Masih Village Tariza Nagar, PO Dhariwal, Gurdaspur 5 2703 Abhay Saini Parvesh Saini house no DF/350,4 Marla Quarter Ram Nagar Pathankot 6 1739 Abhi Bhavnesh Kumar Ward No. 3, Hno. 282, Kothe Bhim Sen, Dinanagar 7 1307 Abhi Nandan Niranjan Singh VPO Bhavnour, tehsil Mukerian , District Hoshiarpur 8 1722 Abhinandan Mahajan Bhavnesh Mahajan Ward No. 3, Hno. 282, Kothe Bhim Sen, Dinanagar 9 305 Abhishek Danial Hno 145, ward No. 12, Line No. 18A Mill QTR Dhariwal, District Gurdaspur 10 465 Abhishek Rakesh Kumar Hno 1479, Gali No 7, Jagdambe Colony, Majitha Road , Amritsar 11 1441 Abhishek Buta Masih Village Triza Nagar, PO Dhariwal, Gurdaspur 12 2195 Abhishek Vijay Kumar Village Meghian, PO Purana Shalla, Gurdaspur 13 2628 Abhishek Kuldeep Ram VPO Rurkee Tehsil Phillaur District Jalandhar 14 2756 Abhishek Shiv Kumar H.No.29B, Nehru Nagar, Dhaki road, Ward No.26 Pathankot-145001 15 1387 Abhishek Chand Ramesh Chand VPO Sarwali, Tehsil Batala, District Gurdaspur 16 983 Abhishek Dadwal Avresh Singh Village Manwal, PO Tehsil and District Pathankot Page 1 POST APPLIED FOR :- PEON Roll No. Application No. Name Father’s Name/ Husband’s Name Permanent Address 17 603 Abhishek Gautam Kewal Singh VPO Naurangpur, Tehsil Mukerian District Hoshiar pur 18 1805 Abhishek Kumar Ashwani Kumar VPO Kalichpur, Gurdaspur 19 2160 Abhishek Kumar Ravi Kumar VPO Bhatoya, Tehsil and District Gurdaspur 20 1363 Abhishek Rana Satpal Rana Village Kondi, Pauri Garhwal, Uttra Khand. -

Administrative Atlas , Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 PUNJAB ADMINISTRATIVE ATLAS f~.·~'\"'~ " ~ ..... ~ ~ - +, ~... 1/, 0\ \ ~ PE OPLE ORIENTED DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB , The maps included in this publication are based upon SUNey of India map with the permission of the SUNeyor General of India. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line. The interstate boundaries between Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya shown in this publication are as interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971 but have yet to be verified. The state boundaries between Uttaranchal & Uttar Pradesh, Bihar & Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh & Madhya Pradesh have not been verified by government concerned. © Government of India, Copyright 2006. Data Product Number 03-010-2001 - Cen-Atlas (ii) FOREWORD "Few people realize, much less appreciate, that apart from Survey of India and Geological Survey, the Census of India has been perhaps the largest single producer of maps of the Indian sub-continent" - this is an observation made by Dr. Ashok Mitra, an illustrious Census Commissioner of India in 1961. The statement sums up the contribution of Census Organisation which has been working in the field of mapping in the country. The Census Commissionarate of India has been working in the field of cartography and mapping since 1872. A major shift was witnessed during Census 1961 when the office had got a permanent footing. For the first time, the census maps were published in the form of 'Census Atlases' in the decade 1961-71. Alongwith the national volume, atlases of states and union territories were also published. -

Growth of Urban Population in Malwa (Punjab)

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 8, Issue 7, July 2018 34 ISSN 2250-3153 Growth of Urban Population in Malwa (Punjab) Kamaljit Kaur DOI: 10.29322/IJSRP.8.7.2018.p7907 http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.8.7.2018.p7907 Abstract: This study deals with the spatial analysis of growth of urban population. Malwa region has been taken as a case study. During 1991-2001, the urban growth has been shown in Malwa region of Punjab. The large number of new towns has emerged in this region during 1991-2001 periods. Urban growth of Malwa region as well as distribution of urban centres is closely related to accessibility and modality factors. The large urban centres are located along major arteries. International border with an unfriendly neighbour hinders urban growth. It indicates that secondary activities have positive correlation with urban growth. More than 90% of urban population of Malwa region lives in large and medium towns of Punjab. More than 50% lives in large towns. Malwa region is agriculturally very prosperous area. So Mandi towns are well distributed throughout the region. Keywords: Growth, Urban, Population, Development. I. INTRODUCTION The distribution of urban population and its growth reflect the economic structure of population as well as economic growth of the region. The urban centers have different socio economic value systems, degree of socio-economic awakening than the rural areas. Although Urbanisation is an inescapable process and is related to the economic growth of the region but regional imbalances in urbanization creates problems for Planners so urban growth need to be channelized in planned manner and desired direction. -

Category Wise Detail of Merit Regarding Post of Steno Typists Who Had Applied in Response to the Advertisement No 1 of 2012

Category wise detail of merit regarding post of steno typists who had applied in response to the advertisement no 1 of 2012 published on 15/5/2012 STENOTYPIST GENERAL SR. NO. NAME OF CANDIDATE FATHER'S NAME DATE OF BIRTH DETAIL REGARDING WHETHER POSSESSES CHALAN NAME OF ADDRESS OF THE CONDIDATE REMARKS GRADUATION 120 HRS COMPUTER NO. DATE BANK YEAR COURSE FROM ISO UNIVERSITY 9001 DETAILED AS BELOW 170001 DAULAT SINGH KAMAL SINGH 6/30/1987 2006 GNDU PGDCA(GNDU) 26 6/6/2012 SBI VPO MUKANDPUR, DISTT SBS NAGAR 170002 GURPREET KAUR SURJEET SINGH 2/10/1986 2008 GNDU PGDCA(EILM) 276 6/6/2012 SBI VILL KOHILIAN, PO DINARANGA, DISTT GURDASPUR 170003 POONAM HARBANS SINGH 9/7/1989 2011 PU C-NET COMPUTER 2640228 6/4/2012 SBI NEAR DEV SAMJ HOSTEL STREET NO1, CENTRE ROSE BEAUTY PARLOR, FEROZEPUR 170004 KULWINDER SINGH HARMAIL SINGH 8/22/1985 2007 PUNJABI PGDCA 385 6/5/2012 SBP MANNA WALI GALI MADHU PATTI, UNIVERSITY H.NOB5 370 BARNALA 170005 JATINDER SINGH DALBARA SINGH 2/25/1990 2012 PTU NA 43 6/5/2012 SBP VILL BATHAN KHURD, PO DULWAN, THE KHAMANO, DISTT FATHEGARH SAHIB 170006 ARUN KUMAR JAGAT SINGH 2/8/1978 1997 PTU NA 17 6/6/2012 SBP VILL GARA, PO AGAMPUR, THE ANANDPUR SAHIB, DISTT ROPAR 170007 RANJIT SINGH MEEHAN SINGH 1/13/1981 2009 PUNJABI B.ED 384 6/5/2012 SBP VILL DHANGARH DISTT BARNALA UNIVERSITY COMPUTER(AIMIT) 170008 VEERPAL KAUR MALKIT SINGH 11/10/1983 2005 PU NA 17 5/30/2012 SBI VILL MAHNA THE MALOUT DISTT MUKTSAR 1 STENOTYPIST GENERAL SR. -

Atms RE CALIBRATED 09.12.2016

S NO ATMID ATM ADDRESS 1 SPSBA007501 E-16, RAJOURI GARDEN, NEW DELHI-110027 2 SPSBA028801 UNIVERSITY,CAMPUS, AMRITSAR 3 SPSBA003101 KHALSA COLLEGE, AMRITSAR 4 SPSBA010201 LAWRENCE ROAD, CIVIL LINES, AMRITSAR 5 SPSBA048701 D-6 SHOPPING CENTRE 11, VASANT VIHAR, NEW DELHI-110057 6 SPSBA090302 DESH BANDHU COLLEGE, KALKAJI, NEW DELHI - 110 019 7 SPSBA061201 7 SIDHARATH ENCLAVE, NEW DELHI -110014 8 SPSBA000701 CHANDNICHOWK FOUNTAIN, NEW DELHI 9 SPSBA056501 C.S.C MARKET, A-BLOCK, DELHI 10 SPSBA015901 SUNET LUDHIANA OPP MILK PLANT,FEROZEPUR ROAD, LUDHIANA 11 SPSBA029301 MODEL TOWN LUDHIANA 12 SPSBA076401 GTB NAGAR, JALANDHAR 13 SPSBA001901 5/1 D.B.ROAD, PAHAR GANJ,NEW DELHI 14 SPSBA000901 RAILWAY ROAD, HOSHIARPUR 15 SPSBA010701 TANDA URMAR DISTT HOSHIARPUR 16 SPSBA072201 PLOT NO: 2, LSC NO: 3, SECTOR-6, DWARKA, DELHI 17 SPSBA053801 195-B, LOHIA NAGAR NEW GHAZIABAD 18 SPSBA052301 FITWEL HOUSE, L B S MARG, VIKHROLI (WEST), MUMBAI, MUMBAI 19 SPSBA064701 MOHAR APARTMENT,L.T.ROAD, BORIVILI(W), BOMBAY 20 SPSBA087801 B-136, PREET VIHAR, NEW DELHI 21 SPSBA087701 D - 31 ACHARYA NIKETAN,MAYUR VIHAR, NEW DELHI 22 SPSBA061301 URBAN ESTATE GARAH ROAD, JALANDHAR PUNJAB 23 SPSBA087101 B55 GAUTAM MARG, HANUMAN NAGAR, JAIPUR PLOT NO. 14 SECTOR 26-A PALM BEACH ROAD KOPRI COLONY, VASHI NAVI 24 SPSBA046701 MUMBAI 25 SPSBA030001 LINKING ROAD, KHAR BOMBAY 26 SPSBA032301 JANGPURA EXTENTION, NEW DELHI 27 SPSBA091701 3 / 536, VIVEK KHAND, GOMTI NAGAR, LUCKNOW 28 SPSBA088301 12 A JAIPURIA SUNRISE GREEN, AHINSA KHAND, INDIRA PURAM GHAZIABAD 29 SPSBA091201 H-32 / 6 SECTOR - 3, ROHINI, NEW DLEHI 30 SPSBA091601 80/19-20/1 GURDWARA ROAD, NAKA HINDOLA, CHAR BAGH, LUCKNOW 31 SPSBA086501 N. -

Role of Dalit Diaspora in the Mobility of the Disadvantaged in Doaba Region of Punjab

DOI: 10.15740/HAS/AJHS/14.2/425-428 esearch aper ISSN : 0973-4732 Visit us: www.researchjournal.co.in R P AsianAJHS Journal of Home Science Volume 14 | Issue 2 | December, 2019 | 425-428 Role of dalit diaspora in the mobility of the disadvantaged in Doaba region of Punjab Amanpreet Kaur Received: 23.09.2019; Revised: 07.11.2019; Accepted: 21.11.2019 ABSTRACT : In Sikh majority state Punjab most of the population live in rural areas. Scheduled caste population constitute 31.9 per cent of total population. Jat Sikhs and Dalits constitute a major part of the Punjab’s demography. From three regions of Punjab, Majha, Malwa and Doaba,the largest concentration is in the Doaba region. Proportion of SC population is over 40 per cent and in some villages it is as high as 65 per cent.Doaba is famous for two factors –NRI hub and Dalit predominance. Remittances from NRI, SCs contributed to a conspicuous change in the self-image and the aspirations of their families. So the present study is an attempt to assess the impact of Dalit diaspora on their families and dalit community. Study was conducted in Doaba region on 160 respondents. Emigrants and their families were interviewed to know about remittances and expenditure patterns. Information regarding philanthropy was collected from secondary sources. Emigration of Dalits in Doaba region of Punjab is playing an important role in the social mobility. They are in better socio-economic position and advocate the achieved status rather than ascribed. Majority of them are in Gulf countries and their remittances proved Authror for Correspondence: fruitful for their families. -

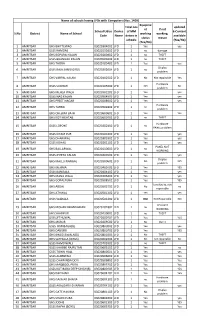

List of Schools Having Lfds

Name of schools having LFDs with Computers (Nos. 1400) Equipme Total nos updated nt If not School Udise Device of MM E-Content S.No District Name of School working working, Code Name deices in available status reason schools (Yes/No) (Yes/No) 1 AMRITSAR GHS BHITTEWAD 03020304002 LFD 1 Yes yes 2 AMRITSAR GSSS RAMDAS 03020111602 LFD 1 no damage 3 AMRITSAR GHS BOPARAI KALAN 03020200402 LFD 1 no THEFT 4 AMRITSAR GSSS BHANGALI KALAN 03020503002 LFD 1 no THEFT 5 AMRITSAR GHS THOBA 03020105402 LFD 1 Yes yes Display 6 AMRITSAR GSSS RAJA SANSI GIRLS 03020302604 LFD 1 no problem 7 AMRITSAR GHS VARPAL KALAN 03020402502 LFD 1 No Not repairable Yes Hardware 8 AMRITSAR GSSS SUDHAR 03020105002 LFD 1 NO No problem 9 AMRITSAR GHS MEHLA WALA 03020302202 LFD 1 Yes yes 10 AMRITSAR GSSS NAG KALAN 03020504903 LFD 1 Yes yes 11 AMRITSAR GHS PREET NAGAR 03020208902 LFD 1 Yes yes Hardware 12 AMRITSAR GHS TARPAI 03020502802 LFD 1 no problem 13 AMRITSAR GHS CHEEMA BATH 03020600602 LFD 1 Yes Yes 14 AMRITSAR GHS KOT MEHTAB 03020600702 LFD 1 no THEFT Hardware 15 AMRITSAR GSSS LOPOKE 03020202402 LFD 1 no PANEL problem 16 AMRITSAR GSSS KIYAM PUR 03020101002 LFD 1 Yes yes 17 AMRITSAR GHS DHARIWAL 03020303302 LFD 1 Yes yes 18 AMRITSAR GSSS KOHALI 03020201102 LFD 1 Yes yes PANEL NOT 19 AMRITSAR GHS BALLARWAL 03020110002 LFD 1 no WORKING 20 AMRITSAR GSSS JHEETA KALAN 03020400102 LFD 1 Yes yes Display 21 AMRITSAR GHS MALLU NANGAL 03020300602 LFD 1 No NO problem 22 AMRITSAR GHS MEHMA 03020400702 LFD 1 Yes YES 23 AMRITSAR GSSS BANDALA 03020404402 LFD 1 Yes yes 24 AMRITSAR GHS -

Song and Memory: “Singing from the Heart”

SONG AND MEMORY: “SINGING FROM THE HEART” hir kIriq swDsMgiq hY isir krmn kY krmw ] khu nwnk iqsu BieE prwpiq ijsu purb ilKy kw lhnw ]8] har kīrat sādhasangat hai sir karaman kai karamā || kahu nānak tis bhaiou parāpat jis purab likhē kā lahanā ||8|| Singing the Kīrtan of the Lord’s Praises in the Sādh Sangat, the Company of the Holy, is the highest of all actions. Says Nānak, he alone obtains it, who is pre-destined to receive it. (Sōrath, Gurū Arjan, AG, p. 641) The performance of devotional music in India has been an active, sonic conduit where spiritual identities are shaped and forged, and both history and mythology lived out and remembered daily. For the followers of Sikhism, congregational hymn singing has been the vehicle through which melody, text and ritual act as repositories of memory, elevating memory to a place where historical and social events can be reenacted and memorialized on levels of spiritual significance. Hymn-singing services form the magnetic core of Sikh gatherings. As an intimate part of Sikh life from birth to death, Śabad kīrtan’s rich kaleidoscope of singing and performance styles act as a musical and cognitive archive bringing to mind a collective memory, uniting community to a common past. As a research scholar and practitioner of Gurmat Sangīt, I have observed how hymn singing plays such a significant role in understanding the collective, communal and egalitarian nature of Sikhism. The majority of events that I attended during my research in Punjab involved congregational singing: whether seated in the Gūrdwāra, or walking in a procession, the congregants were often actively engaged in singing. -

Pincode Officename Statename Minisectt Ropar S.O Thermal Plant

pincode officename districtname statename 140001 Minisectt Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Thermal Plant Colony Ropar S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140001 Ropar H.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Morinda S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140101 Bhamnara B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Rattangarh Ii B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Saheri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Dhangrali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140101 Tajpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Lutheri S.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Rollumajra B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Kainaur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Makrauna Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Samana Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Barsalpur B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140102 Chaklan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140102 Dumna B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140103 Kurali S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Allahpur B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Burmajra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Chintgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Dhanauri B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Jhingran Kalan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Kalewal B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Kaishanpura B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Mundhon Kalan B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sihon Majra B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Singhpura B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140103 Sotal B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140103 Sahauran B.O Mohali PUNJAB 140108 Mian Pur S.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Pathreri Jattan B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Rangilpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Sainfalpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Singh Bhagwantpur B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Kotla Nihang B.O Ropar PUNJAB 140108 Behrampur Zimidari B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Ballamgarh B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140108 Purkhali B.O Rupnagar PUNJAB 140109 Khizrabad West S.O Mohali PUNJAB 140109 Kubaheri B.O Mohali PUNJAB