Desert Enlightenment: Prophets and Prophecy in American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapterhouse: Dune Frank Herbert April 1985 Those Who Would Repeat

Chapterhouse: Dune Frank Herbert April 1985 Those who would repeat the past must control the teaching of history. -Bene Gesserit Coda When the ghola-baby was delivered from the first Bene Gesserit axlotl tank, Mother Superior Darwi Odrade ordered a quiet celebration in her private dining room atop Central. It was barely dawn, and the two other members of her Council -- Tamalane and Bellonda -- showed impatience at the summons, even though Odrade had ordered breakfast served by her personal chef. "It isn't every woman who can preside at the birth of her own father," Odrade quipped when the others complained they had too many demands on their time to permit of "time-wasting nonsense." Only aged Tamalane showed sly amusement. Bellonda held her over-fleshed features expressionless, often her equivalent of a scowl. Was it possible, Odrade wondered, that Bell had not exorcised resentment of the relative opulence in Mother Superior's surroundings? Odrade's quarters were a distinct mark of her position but the distinction represented her duties more than any elevation over her Sisters. The small dining room allowed her to consult aides during meals. Bellonda glanced this way and that, obviously impatient to be gone. Much effort had been expended without success in attempts to break through Bellonda's coldly remote shell. "It felt very odd to hold that baby in my arms and think: This is my father," Odrade said. "I heard you the first time!" Bellonda spoke from the belly, almost a baritone rumbling as though each word caused her vague indigestion. She understood Odrade's wry jest, though. -

Introduction to Astronomy from Darkness to Blazing Glory

Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory Published by JAS Educational Publications Copyright Pending 2010 JAS Educational Publications All rights reserved. Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Second Edition Author: Jeffrey Wright Scott Photographs and Diagrams: Credit NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USGS, NOAA, Aames Research Center JAS Educational Publications 2601 Oakdale Road, H2 P.O. Box 197 Modesto California 95355 1-888-586-6252 Website: http://.Introastro.com Printing by Minuteman Press, Berkley, California ISBN 978-0-9827200-0-4 1 Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory The moon Titan is in the forefront with the moon Tethys behind it. These are two of many of Saturn’s moons Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, ISS, JPL, ESA, NASA 2 Introduction to Astronomy Contents in Brief Chapter 1: Astronomy Basics: Pages 1 – 6 Workbook Pages 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Time: Pages 7 - 10 Workbook Pages 3 - 4 Chapter 3: Solar System Overview: Pages 11 - 14 Workbook Pages 5 - 8 Chapter 4: Our Sun: Pages 15 - 20 Workbook Pages 9 - 16 Chapter 5: The Terrestrial Planets: Page 21 - 39 Workbook Pages 17 - 36 Mercury: Pages 22 - 23 Venus: Pages 24 - 25 Earth: Pages 25 - 34 Mars: Pages 34 - 39 Chapter 6: Outer, Dwarf and Exoplanets Pages: 41-54 Workbook Pages 37 - 48 Jupiter: Pages 41 - 42 Saturn: Pages 42 - 44 Uranus: Pages 44 - 45 Neptune: Pages 45 - 46 Dwarf Planets, Plutoids and Exoplanets: Pages 47 -54 3 Chapter 7: The Moons: Pages: 55 - 66 Workbook Pages 49 - 56 Chapter 8: Rocks and Ice: -

The Working Planetologist Speculative Worlds and the Practice of Climate Science

Chapter 2: The Working Planetologist Speculative Worlds and the Practice of Climate Science Katherine Buse In a 2010 editorial in the journal Nature, the climate scientist and Executive Direc- tor of the International Geosphere–Biosphere Programme, Sybil Seitzinger, ar- gues that scientists ought to be more centrally involved in international policy dis- cussions about sustainable development. “In Frank Herbert’s 1965 science-fiction classic Dune,” she writes, “the number-one position on the planet is held not by a politician, but by a planetary ecologist” (Seitzinger 2010: 601). Seitzinger invokes Herbert’s novel here to make a pointed comparison. In Dune, the inhabitants of the planet Arrakis are engaging in a long-term terraforming project that neces- sitates the oversight of a planetary ecologist. But here on Earth, we too have been making such changes, “altering, in profound and uncontrolled ways, key biologi- cal, physical and chemical processes of ecosystems.” For Seitzinger, grappling re- sponsibly with these processes requires a global, far-sighted perspective that she finds lacking in most Earth politicians. She advises that, while the governments of Earth have not yet considered appointing a planetary ecologist, “perhaps it is time to take the idea seriously.” And she is dead serious, both as a worried scientist and policy analyst, and also as a reader of Dune. Although she discusses the novel explicitly only in the first and last sentences of her editorial, Seitzinger does not invoke Dune merely to provide a bit of ‘science communication’ flavor to entertain Nature’s interdisciplinary read- ership. After all, the perspective she takes in the editorial is profoundly similar to Frank Herbert’s vision in Dune: both pragmatic and theoretical, it subsumes socio-political concerns as components of a planetary ecological model. -

Atreides Bene Gesserit Emperor Harkonnen Spacing Guild Fremen

QUICK START GUIDE Frank Herbert’s classic science fiction novelDune will live for generations as a masterpiece of creative imagination. In this game, you can bring to life the alien planet and the swirling intrigues of all the book’s major characters. Atreides Harkonnen The Atreides led by the The Harkonnens, led youthful Paul Atreides by the decadent Baron (Muad’Dib) — rightful Vladimir Harkonnen — heir to the planet, gifted master of treachery and with valiant lieutenants. cruel deeds. Bene Spacing Gesserit Guild The Bene Gesserit The Spacing Guild Sisterhood, represented represented by by Reverend Mother steersman Edric (in Gaius Helen Mohiam — league with smuggler ancient and inscrutable. bands) — monopolist of transport, yet addicted to ever increasing spice flows. Emperor Fremen The Emperor, his The Fremen majesty the Padishah represented by the Emperor Shaddam IV planetary ecologist Liet- — keen and efficient, Kynes — commanding yet easily lulled into fierce hordes of natives, complacency by his own adept at life and travel trappings of power. on the planet. SETUP: SPICE BANK SETUP: TREACHERY & SPICE DECKS, STORM MARKER I’m Lady Jessica of the House Atreides. Prepare to become immersed in the world of Dune. Here’s Feyd-Rautha of House Harkonnen here. how to set everything up. We are masters of treachery and cruel deeds! Next, shuffle the Treachery & Spice Decks and set them next to the board. I am Stilgar of the Fremen. We are adept Staban Tuek, at life and travel on of the Spacing the planet Dune. Guild coalition. First set out the We control all game board map. shipments on and off Dune. -

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

Scary Movies at the Cudahy Family Library

SCARY MOVIES AT THE CUDAHY FAMILY LIBRARY prepared by the staff of the adult services department August, 2004 updated August, 2010 AVP: Alien Vs. Predator - DVD Abandoned - DVD The Abominable Dr. Phibes - VHS, DVD The Addams Family - VHS, DVD Addams Family Values - VHS, DVD Alien Resurrection - VHS Alien 3 - VHS Alien vs. Predator. Requiem - DVD Altered States - VHS American Vampire - DVD An American werewolf in London - VHS, DVD An American Werewolf in Paris - VHS The Amityville Horror - DVD anacondas - DVD Angel Heart - DVD Anna’s Eve - DVD The Ape - DVD The Astronauts Wife - VHS, DVD Attack of the Giant Leeches - VHS, DVD Audrey Rose - VHS Beast from 20,000 Fathoms - DVD Beyond Evil - DVD The Birds - VHS, DVD The Black Cat - VHS Black River - VHS Black X-Mas - DVD Blade - VHS, DVD Blade 2 - VHS Blair Witch Project - VHS, DVD Bless the Child - DVD Blood Bath - DVD Blood Tide - DVD Boogeyman - DVD The Box - DVD Brainwaves - VHS Bram Stoker’s Dracula - VHS, DVD The Brotherhood - VHS Bug - DVD Cabin Fever - DVD Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh - VHS Cape Fear - VHS Carrie - VHS Cat People - VHS The Cell - VHS Children of the Corn - VHS Child’s Play 2 - DVD Child’s Play 3 - DVD Chillers - DVD Chilling Classics, 12 Disc set - DVD Christine - VHS Cloverfield - DVD Collector - DVD Coma - VHS, DVD The Craft - VHS, DVD The Crazies - DVD Crazy as Hell - DVD Creature from the Black Lagoon - VHS Creepshow - DVD Creepshow 3 - DVD The Crimson Rivers - VHS The Crow - DVD The Crow: City of Angels - DVD The Crow: Salvation - VHS Damien, Omen 2 - VHS -

The Enduring Power of Musical Theatre Curated by Thom Allison

THE ENDURING POWER OF MUSICAL THEATRE CURATED BY THOM ALLISON PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY NONA MACDONALD HEASLIP PRODUCTION CO-SPONSOR LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. CURATED AND DIRECTED BY THOM ALLISON THE SINGERS ALANA HIBBERT GABRIELLE JONES EVANGELIA KAMBITES MARK UHRE THE BAND CONDUCTOR, KEYBOARD ACOUSTIC BASS, ELECTRIC BASS, LAURA BURTON ORCHESTRA SUPERVISOR MICHAEL McCLENNAN CELLO, ACOUSTIC GUITAR, ELECTRIC GUITAR DRUM KIT GEORGE MEANWELL DAVID CAMPION The videotaping or other video or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

QUESTIONS on BOOK TWO Professor Corey Olsen Mythgard Institute Questions on Book Two

QUESTIONS ON BOOK TWO Professor Corey Olsen Mythgard Institute Questions on Book Two 1. The Irulan Oeuvre, Book II In My Father’s House (3) Conversations with Muad’Dib (1) Arrakis Awakening (2) Manual of Muad’Dib (2) A Child’s History of Muad’Dib (1) Muad’Dib: Conversations (1) Private Reflections on Muad’Dib (1) The Wisdom of Muad’Dib (2) Collected Sayings of Muad’Dib (1) Muad’Dib, the Man (1) Questions on Book Two 2. Untold Stories (Matt Shaw) Like Tolkien, Herbert hints at reams of history and back-story in brief passages: “It reads like the Azhar Book, she thought, recalling her studies of the Great Secrets. Has a Manipulator of Religions been on Arrakis?” Manipulator of Religions? That sounds vaguely awesome. Not to mention that “Great Secrets” is capitalized, which suggests much. My quick take: In the Dune universe, every meeting is a test and every conversation is a performance. They’re not much for the small talk. Or perhaps they favor Small Talk. Questions on Book Two 3. The Polyglot World (Yves de Gennip) Thinking back about the discussion about the OC Bible in one of the lectures, I was reminded of my own impressions when reading Dune for the first time back in my teens. Being Dutch, clearly I couldn’t help but wondering if the “orange” part had anything to do with The Netherlands (which, indirectly, it has, if the connection with Protestantism is a valid one, as discussed in the lecture). This feeling was only enforced by the word “Landsraad”, which is a Dutch word, or, more accurately, it is a combination of two Dutch words, “land” (which in itself could of course also be English) and “raad” (council). -

![Arxiv:2005.14671V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 30 Jun 2020 Tion Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8147/arxiv-2005-14671v2-astro-ph-ep-30-jun-2020-tion-et-al-408147.webp)

Arxiv:2005.14671V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 30 Jun 2020 Tion Et Al

Draft version July 1, 2020 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX62 The Gaia-Kepler Stellar Properties Catalog. II. Planet Radius Demographics as a Function of Stellar Mass and Age Travis A. Berger,1 Daniel Huber,1 Eric Gaidos,2 Jennifer L. van Saders,1 and Lauren M. Weiss1 1Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai`i, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 2Department of Earth Sciences, University of Hawai`i at M¯anoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA ABSTRACT Studies of exoplanet demographics require large samples and precise constraints on exoplanet host stars. Using the homogeneous Kepler stellar properties derived using Gaia Data Release 2 by Berger et al.(2020), we re-compute Kepler planet radii and incident fluxes and investigate their distributions with stellar mass and age. We measure the stellar mass dependence of the planet radius valley to +0:21 be d log Rp/d log M? = 0:26−0:16, consistent with the slope predicted by a planet mass dependence on stellar mass (0.24{0.35) and core-powered mass-loss (0.33). We also find first evidence of a stellar age dependence of the planet populations straddling the radius valley. Specifically, we determine that the fraction of super-Earths (1{1.8 R⊕) to sub-Neptunes (1.8{3.5 R⊕) increases from 0.61 ± 0.09 at young ages (< 1 Gyr) to 1.00 ± 0.10 at old ages (> 1 Gyr), consistent with the prediction by core-powered mass- loss that the mechanism shaping the radius valley operates over Gyr timescales. Additionally, we find a tentative decrease in the radii of relatively cool (Fp < 150 F⊕) sub-Neptunes over Gyr timescales, which suggests that these planets may possess H/He envelopes instead of higher mean molecular weight atmospheres. -

Here Is the Much Requested List of Dune Novels and Short Stories in Chronological Order

Here is the much requested list of Dune novels and short stories in Chronological Order 1. "Hunting Harkonnens" (Included in Tales of Dune) 2. The Butlerian Jihad 3. "Whipping Mek" (Included in Tales of Dune) 4. The Machine Crusade 5. "The Faces of a Martyr" (Included in Tales of Dune) 6. The Battle of Corrin 7. Sisterhood of Dune 8. Mentats of Dune 9. "Red Plague" (takes place immediately before Navigators of Dune; Included in Tales of Dune) 10. Navigators of Dune 11. House Atreides 12. House Harkonnen 13. "Blood and Water" (standalone excerpt from House Harkonnen) 14. House Corrino 15. “Fremen Justice” (Also published as “Nighttime Shadows of Open Sand,” standalone excerpt from House Corrino) 16. “Wedding Silk” (Included in Tales of Dune) 17. The Duke of Caladan 18. The Lady of Caladan (forthcoming) 19. The Heir of Caladan (forthcoming) 20. Frank Herbert's Dune 21. “A Whisper of Caladan Seas” (takes place during events of Dune; Included in Tales of Dune) 22. "The Waters of Kanly" (takes place during events of Dune; Included in the short story collection, Infinite Stars edited by Bryan Thomas Schmidt) 23. Paul of Dune 24. Frank Herbert's Dune Messiah 25. The Winds of Dune 26. Frank Herbert's Children of Dune 27. Frank Herbert's God-Emperor of Dune 28. Frank Herbert's Heretics of Dune 29. Frank Herbert's Chapterhouse; Dune 30. “Sea Child” (takes place during events of Chapterhouse; Dune; Included in Tales of Dune) 31. Hunters of Dune 32. “Treasure in the Sand” (takes place immediately before Sandworms of Dune; Included in Tales of Dune) 33. -

Frank Herbert's Dune

D U N E Part One by John Harrison Based on the novel by Frank Herbert Revisions 11/15/99 © 1999 New Amsterdam Entertainment, Inc. Converted by duneinfo.com 1. A1 FADE IN: A black void where... A PLANET slowly emerges. Forming in orange/gold mists. Desolate, monochromatic contours. No clouds. Just a thin cover of cirrus vapor. And somewhere... A mechanical voice...lecturing with monotonous precision. VOICE ....Arrakis...Dune...wasteland of the Empire. Wilderness of hostile deserts and cataclysmic storms. Home to the monstrous sandworm that haunts the vast desolation. The only planet in the universe where can be found...the SPICE. Guardian of health and longevity, source of wisdom, gateway to enhanced awareness. Rare and coveted by noble and commoner alike. The spice! Greatest treasure in the Empire... And now...ANOTHER VOICE. Not mechanical. BARON HARKONNEN And so it begins. The trap is set. The prey approaches... Suddenly the planet becomes transparent. It's a HOLOGRAM! And there behind it... The face of BARON VLADIMIR HARKONNEN. Staggeringly obese. Staring with intimidating intensity at the 3D globe suspended in front of him. The calm of his voice is frightening. BARON HARKONNEN A glorious winter is about to descend on House Atreides and all its heirs. The centuries of humiliation visited upon my family will finally be avenged. Behind him... MALE VOICE (RABBAN) BUT ARRAKIS WAS MINE. ANOTHER VOICE (FEYD) Shut up, Rabban! The Baron turns. REVEALING... 2. 1 EXT. BARON'S SUITE...HARKONNEN PALACE - NIGHT ...his NEPHEWS...GLOSSU RABBAN...AKA "the Beast"...his fat sweaty face twisted with rage. -

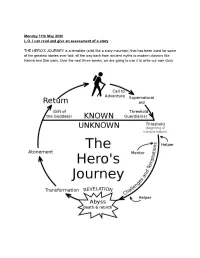

Monday 11Th May 2020 L.O. I Can Read and Give an Assessment of a Story

Monday 11th May 2020 L.O. I can read and give an assessment of a story THE HERO’S JOURNEY is a template (a bit like a story mountain) that has been used for some of the greatest stories ever told, all the way back from ancient myths to modern classics like Narnia and Star wars. Over the next three weeks, we are going to use it to write our own story One of the reasons STAR WARS is such a great movie is it because it follows the HERO’S JOURNEY model. Today, you are going to read / watch this version of the Hero’s journey and see how it fits into the format for our first act! The subtitles just refer to the stages of the story - don’t worry about them yet! Just read the story and if you have internet access look up / click on the clips on youtube. ORDINARY WORLD Luke Skywalker was a poor and humble boy who lived with his aunt and uncle in a scorching and desolate planet world called Tatooine. His job was to fix robots on the family farm and and he spent his free time flying planes through the rocky canyons. He loved his aunt and uncle but dreamed of a more exciting and adventurous life https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8wJa1L1ZCqU Search for ‘Luke Skywalker binary sunset’ CALL TO ADVENTURE One day, Luke found a broken old R2 astromech droid. It was called R2-D2 and it was a mischievous, cheeky robot who made lots of bleeps and flashes.